Walking through Surrealism and Us, there’s a part of the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth where the new exhibit and the building tease each other. The spot sits to the right of one of the sculptural displays. As the curving mounted shapes scuffle with the myriad silver vertical lines of Tadao Ando’s glassy, steely conjoined boxes rising and falling outside like Matrix code on a Magnavox TV circa 1952, with the weak-tea-green reflecting pool below screaming, “Serenity now!,” the resulting vertigo warps not only space but time itself. Surrealism isn’t just nostalgic whimsy. And it’s not just whimsy here. It’s active permanence. Even resistance.

The “state of contemporary art is rumbly,” the “right soundtrack” for an industry “locked in a deadly serious arms race of whimsy.” The New Yorker’s sweeping opinion was written recently in reaction to the 60th annual Venice Biennale, the biggest, most important group show on the planet. The magazine implicitly argues that whimsy equals a firm rejection of (often harsh, mostly brutal) reality. Democracy is dying. The world is burning. Housewives or Dateline and bottomless mojitos — and whimsical art — command our downtime and what’s left of our bandwidth. This distraction-action, though, could also mean we’re just gathering strength for the next fight. We’ve come a long way since, say, 1924, when André Breton published his Manifesto of Surrealism …

Many miles lie ahead of us, and with Surrealism and Us, the Modern offers as a creative, perhaps IRL alternative the genre that was once an entire political movement that crisscrossed the West, even landing in such non-bougie locales as the Caribbean and clearly arriving with a resonant, sparkling musicality. Kind of like us when we step off the cruise ship in Nassau.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.

******

Organized by Curator María Elena Ortiz, Surrealism and Us is “the first intergenerational show dedicated to Caribbean and African diasporic art presented at the Modern.” Comprising more than 80 pieces from the 1940s to the present in nearly every medium, the exhibit takes its title from a 1943 essay by Martinican thinker Suzanne Césaire. Many Caribbean and Black artists, evidently, gravitated toward the movement. Some to make a statement. Others to channel the universe or the universal mind. Even others to do some Voodoo.

The practice is in the soil, in the air. Brought over along with several other religions by enslaved Africans centuries earlier, Voodoo — or Vodun/Voudu (Haiti), Ju-Ju (Bahamas), Santería (Cuba), Obeah (Jamaica), and Shango (Trinidad) — came to be from the belief that God was so distant, we mortals needed spirits to intervene with Him. Praying, sacrificing animals, venerating ancestors, banging drums, channeling spirits — it all helped the slaves not only cope with the inhumanity crushing them but also resist against the Spanish, French, and even the U.S. Marines. The art of the West Indies carried on the revolutionary tradition asymmetrically: not with text necessarily or outright propaganda — or with guns or bombs — but with mind-expanding imagery.

Open minds are empathetic, and empathetic minds make life better for everyone.

Betye Saar’s mind has always been on us.

“To me,” the 97-year-old Angeleno has said, “the trick is to seduce the viewer. If you can get the viewer to look at a work of art, then you might be able to give them some sort of message.”

“The View from the Sorcerer’s Window” unwinds like a tarot card reading. Saar’s assemblage consists of a compact vertical windowpane three panels high teeming with stars and moons, occult symbols, and an all-seeing or visionary eye, a human eye in the palm of an open hand. The piece suggests that the celestial and terrestrial worlds connect in more ways than we may ever know.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.

For Jacques-Enguerrand Gourgue, Voudu simmered beneath his own Port-au-Prince roof — his mother was reportedly a Voudu priestess (and his father was a French psychiatrist, a different sort of dark art). Rural Haitian life and Voudu ceremonies typically busied Gourgue’s canvases, including 1947’s “Huitieme Chambre (The Eighth Room),” finished when he was 17 years old. There’s a lot going on here. In one foregrounded chamber connected to seven others behind it by a hallway receding from near the center of the frame, a Black man with a giant silver machete protruding from his torso lies bleeding on a bed beneath which a long brown snake stretching through all the rooms drinks the blood. A Black man bedside wearing a scowl and a fancy hat folds his arms while sitting on a chair that is actually an ox — you can tell by its horned face atop the seatback. Solid red fires burn in each space as a smaller Black figure (also fancily hatted) does a split (?!) in his brown pants on the floor near some offerings (bottles, another machete, a cup). The Surrealism is not in the flattened, almost cartoonish form. It’s in the exuberantly imaginative content. In style, “The Eighth Room” resembles “The Magic Table,” another Gourgue from the same year that’s been part of MoMA’s permanent collection for decades.

One Surrealism and Us contributor was a Voodoo priest. Hector Hyppolite has two works here, and they’re both wonderfully nuts. “Macanda,” in which grotesque, winged, brown-skinned humanoids like The Beatles’ Blue Meanies hover over a supine, blanketed Black man, is a reference to 18th-century Haitian rebel leader François Makandal. Born in Africa, enslaved in Haiti, and convicted of attempting to poison thousands of plantation owners, Makandal may have — quite possibly could have — escaped being burned at the stake. Either way, he’s a legend now.

Hyppolite’s other offering, “Damballah Le Flambeau,” pays homage to one of Voudu’s or Obeah’s most important iwa, or spirits. In the painting, the debonairly mustachioed Damballah takes the form of winged serpent, curling up in lush vegetation. In Haiti in 1945, Hyppolite, an early forefather of Afrosurrealism, met with another, famous Surrealism and Us contributor, Wifredo Lam, and with Breton, both of whom would go on to promote Hyppolite’s work, ultimately landing the Voudu priest here, in Fort Worth, in Texas, in the United States, at the cusp of another civil war.

Until her death in 1987 at the age of 95, Minnie Evans tapped into something special, and while it wasn’t occultish or dangerous, or revolutionary, like some mind-altering artistic genre or some individualist religion born of torment and death, it was mystical. Inspired by her Christian faith and the flowers and trees where she worked as a gatekeeper in her native North Carolina, the outsider infused her prismatic, mandalic pictures with various folk-art flavors from around the world. In Free within Ourselves: African-American Artists in the Collection of the National Museum of American Art, Evans claimed an antediluvian message from the Lord came to her.

“This art that I have put out has come from the nations I suppose might have been destroyed before the flood,” she said. “No one knows anything about them, but God has given it to me to bring [them] back into the world.”

In subject matter and color, Evans — through divine intervention, coincidence, or Jung’s collective unconscious, a.k.a. that universal mind (or maybe even a few magazines, books, and newspapers of the time) — harked to diverse elements in the folk art of East India, Africa, China, the Caribbean, and more. At the Modern, her small, bilaterally symmetrical, hallucinatory images in various media (ink, pencil/oil, crayon, gouache, collage) mirror Madhubani paintings. Juicy bulbs of refulgent plantlife radiate outward and fold in on one another, which is in keeping with not only the East Indian style but many of the other ancient folk-art traditions that Evans quite possibly miraculously channeled. These pieces are small and not in a prominent place in the show, but don’t miss them.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.

******

As you might imagine for a third-world island nation in the mid-20th century, a lot of the artists there inspired by religion or politics were self-taught, and even the ones who weren’t acknowledged the primitivist nature of their culture. Not only acknowledged it but celebrated it. It was a way of reclaiming the past, their proud heritage. And a way of promoting it.

The native Caribbeans’ renderings were faithful to the stories of old. Depictions of animals and the creation of the world and also of heroes delivering cultural gifts to the masses informed most of the paintings, drawings, and sculptures across the territory. Like only a couple other Surrealism and Us contributors, Lam asserted that primitivism was no less deserving of a place in the Eurocentric art world as any other, fine style. He made sure of that.

“My painting is an act of decolonization,” he said, “not in a physical sense but in a mental one.”

Working mostly in Spain, Paris, and his native Cuba from the late 1920s until his death in 1982, Lam specialized in primitive art inspired by his homeland and in Cubism, a particularly Eurocentric movement that peaked in the 1940s.

Lam’s two contributions to Surrealism and Us are Cubist: 1951’s “Les Mains Croisés (The Crossed Hands),” a portrait of a shrouded horse-like humanoid with clasped hands at waist level, and “Le Sombre Malembo, Dieu du carrefour (Dark Malembo, God of the Crossroads)” from 1943, the same year Lam produced one of his signature works, “Omi Obini,” which recently commanded $9.6 million at auction, a record for him. In “Malembo,” the first large piece to greet museumgoers as they enter the exhibit proper, the artist nods to his verdant homeland by giving us an expansively green backdrop for several abstracted figures to become entangled like some horror-movie monster. A two-headed horse comes to mind. Except the faces are humanoid. And semi-cartoonish. And one of them has horns. Or antlers. The devilish touch is fun, decidedly naive. At this point, the accompanying texts and Googled quotes dissipate like the smoke from an extinguished novena candle. For the sake of this conversation, Malembo was a slave trade station in West Africa and the horny guy is apparently Eleguá, the spirit in Santería who rules over crossroads and determines our fates. It’s a strong piece. It was also ingenious at the time. There weren’t a lot of mashups of childlike primitivism and the avant-garde. By intertwining the folk cultures he loved so much with newness, Lam helped establish a new, non-Eurocentric lingua franca. His nonverbal revolution spoke to everyone.

One delightful, downright joyous piece in a museum overflowing with high, mostly eldritch strangeness is “Momma’s Family.” Made up of several differently shaped gold copper pans imprinted with primitivist faces, native Dallasite Hugh Hayden’s hanging 2024 sculpture looks like a quiet choir singing all of our praises. Again, when up against the kinds of odds we equality lovers are, humor gives us a chance to take some deep breaths before soldiering onward, once again to the breach — not to the beach like Ted Cruz during a climate crisis while a broken billionaire-buddy electrical grid grinds on phlegmatically.

And Agustín Cárdenas’ reliquary-esque figures, the sculptural displays near the Matrix part of the Modern, draw precisely from his Afro-Cuban roots. Sleek and amorphous, they’re totems to conversation as an agent of change as opposed to guns, swords, or other weapons, even manifestos. The inky, medium-sized pieces look like they weigh a ton but have a poetic ebullience about them. There’s no anger or rage here. It’s just pure enticement for the viewer’s pleasure.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.

******

To capture the “genuinely surreal nature of everyday life in the Caribbean,” MoMA says, Alejo Carpentier riffed on the West’s “magic realism” to arrive at lo real maravilloso, or “the marvelous real.” The famous Cuban novelist also tapped into the source.

“Hate of the marvelous,” Breton wrote, “rages in certain men, this absurdity beneath which they try to bury it. Let us not mince words: The marvelous is always beautiful. Anything marvelous is beautiful. In fact, only the marvelous is beautiful.”

We’re to believe that traveling between the physical realms and the ones considered mystical, or marvelous, happened all the time in the West Indies, and from there, the experience radiated through space and time. In a lot of ways, the turbulence of history lives on, here, at democracy’s night and the planet’s end. Fittingly, a decent amount of contemporary art populates Surrealism and Us.

The gravitas of a milestone helps underline the exhibit’s significance now. Maybe we learned a thing or two in the 100 years between Breton’s treatise and today. We know what the white-guy artists thought of it — the average Important Museum groans with their handiwork. What about everyone else?

What about the Caribbean? It’s close enough to us to seem familiar but far enough away to appear entirely, marvelously foreign, the perfect locus for our sensibilities. We museumgoing folk are an equality-minded people. We love the old (dead) white guys, but let’s see some new, colorful faces with something to say. And maybe some spirits to conjure.

Surrealism and Us aims to please on that point. One new-to-me voice is Kenny Rivero. Seen on a lot of the exhibit’s advertising, the New Yorker’s painting “Olafs and Chanclas” does whimsy justice. Two Black children costumed in white sheets with holes cut out for the eyes stand on either side of another all-seeing or visionary eye. The title card tells us Rivero is a Dominican American drawing from his Big Apple childhood and his mother’s family’s Afro-Caribbean “spiritual practices” (probably Vudú). What’s inspiring about this piece isn’t anything literal, definitely not anything overtly political. It’s that humor and the playful shock of such a never-before-seen image legitimately challenge the norm. Is emailing a scrap of automatic writing to Sweaty Teddy Cruz the equivalent of voting against him? No. We’re just saying that by opening our (possibly empty, definitely white) eyes to not just one possibility but an infinity’s worth of them, we can put the U.S. senator from Houston out of a job. Or at the very least learn some empathy.

Rivero synthesizes iconic imagery to tell visual poems — automatic writing for the eyes. He’s an inspired, mostly figurative narrativist and, unsurprisingly for such a nonconceptual show, one of several here.

The best-known — and arguably the best contemporary art has to offer, thanks to her biting style — Kara Walker consumes an entire side gallery. Peeking into the cavernous room reveals sweltering splotches of red, green, blue, white, and black across which the Californian’s black-silhouetted grotesqueries unfold linearly in both directions.

If Rivero’s tableaux tickle, Walker’s nightmarish Antebellum horror novels terrify. For a palate cleanser, make your way to Stanley Greaves.

The 90-year-old Guyanese’s paintings aren’t sinister. They merely betray a weird, gloomy sci-fi or marvelous-realism bent that’s spooky-intellectual rather than spooky-visceral like Walker’s stuff. Basically, Greaves’ images aren’t going to follow you home.

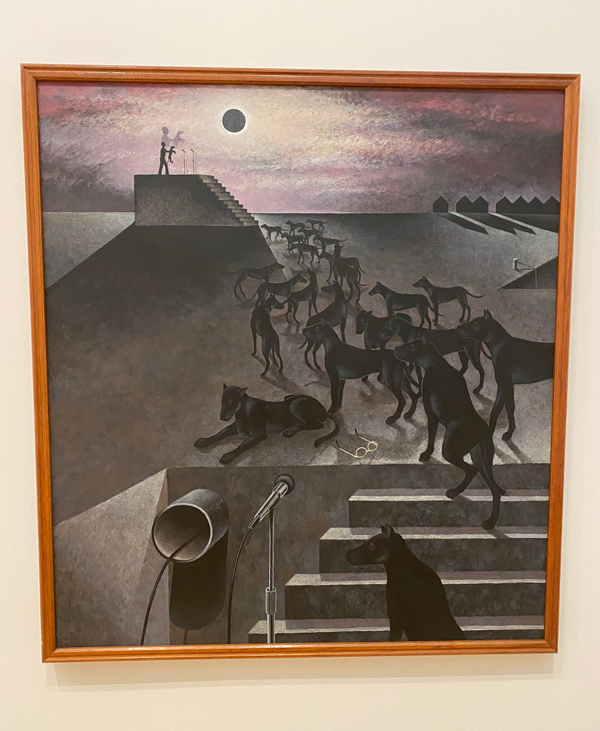

They’ll definitely put you in a mood. “The Apotheosis” could have been an OMNI magazine cover. A pack of shadowy black hounds winds up stairs beneath a solar eclipse to a raised platform on which a man standing holds up a puppy to the night sky and a microphone. Like this piece, Greaves’ other contribution is also part of his epic 14-painting series There Is a Meeting Here Tonight (1992-2001). In “Election Results,” a shirtless Black man in the foreground offers us a loaf of bread and a microphone while behind him on a line, a fish dangles, referring to Jesus. The symbolism here tells me that there’s a … catch … to taking the bait. As a lot of church leaders know, unfortunately: Keeping the flock well-fed is just as important as scaring the crap out of them with cultural bogeymen.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.

*****

As great as Surrealism and Us is, some pieces seem forced. We all love Kerry James Marshall, but his realistic birds on branches rely way too much on the accompanying text for any “Surrealist” heft than the canvas itself. Same for a couple other works. Most of them look fabulous but may not honestly qualify as “surreal.” Enough nitpicking.

This all brings up the recent kerfuffle about art criticism itself. In a story in the Manhattan Art Review, the editor said it’s OK for critics to dwell — at length — on their misgivings about certain shows or works of art: “Writing about art can have any number of objectives, but lurking behind any analysis is the question of judgment. Most contemporary art writing uses interpretation as a way of sidestepping the problem of quality, but interpretations are impossible to take seriously if the art itself is bad.”

While I mostly agree with him, I’m not quite sure what the point is. One reason overtly nasty criticism evades us readers is that there’s just not enough appetite for needless invective. It does no one any good. Not the reader and certainly not the artist. And I can only think that all that cleverness in the mean art critic’s screed could have been better applied to another format. Maybe a poem. Or a crust-punk song. Or a pulp novel. Look at Kevin Smith. After his heart attack, the filmmaker said he stopped hating things, saying he’d rather focus his energies on what he loves. The high road is always there. Taking it takes strength.

And I’ve always loved Sontag. “Lovingly” describing a work of art, as she’s said, should be the critic’s primary responsibility. Unless there’s some sort of Art Critic Test we all must pass before visiting any museum or gallery then popping off, or maybe even before rolling into Target to choose between an autumnal-road print or a still life of a water pump with some sunflowers, subjectivity cannot be defeated.

To a point. Anything referential or derivative will/should be ignored while the rest — on the walls, onscreen, onstage, or on the page — will/should go on being “lovingly” recreated in words.

“Reality cannot be ignored except at a price,” Aldous Huxley said, “and the longer the ignorance is persisted in, the higher and more terrible becomes the price that must be paid.”

That’s fine, Brave New Guy, but we’re not necessarily talking about eschewing what’s in front of us, touching us, starving us, choking us, bombing us to the detriment of our life as if it were a tit-for-tat proposition. What we’re talking about, and what Surrealism and Us suggests, is a shift in perception, from the literal to the metaphoric, and in that switch, we can terrorize the establishment in multihued, unexpected, certainly delightful ways.

Photo by Anthony Mariani.