Jon Ruhl’s debut album might be out now, but his journey to get there started long ago — and reached its apex in 2015. That’s when he spent 10 days in a Peruvian jungle as part of an ayahuasca retreat. His experience in South America with the powerfully hallucinogenic indigenous plant medicine was transformative, inspiring the 26-year-old folk-rock singer-songwriter and helping him cope with the severe trauma he had been battling from his time as a U.S. Marine Corps field medic in Afghanistan five years before his trip. He recorded his self-titled debut album in Fort Worth at Niles City Sound (Leon Bridges, Vincent Neil Emerson, Quaker City Night Hawks) in January 2021, accompanied by drummer Dennis Ryan from Deer Tick (Dave Matthews’ ATO Records) and Will Van Horn on pedal steel, with Robert Ellis producing as well as adding bass, guitars, keys, and percussion. The album was largely inspired by Ruhl’s troubled childhood in Mississippi but also touches on his life and travels since then, including a 14-month period when he lived out of his converted camper van. Jon Ruhl carries on in the tradition of some of his most beloved artists, such as John Hartford, Jimmy Buffet, Don Williams, and Jerry Jeff Walker.

As a teenager, Ruhl wasn’t someone you would ordinarily think of as a Marine. He began playing guitar at 15 after being grounded by his father for an entire summer and started writing his own music soon after. By 19, he was performing in bars while living in Pensacola, Florida. In 2020, he struck up a friendly correspondence with Ellis, who’s played with Willie Nelson and Paul Simon and co-owns Niles City, and that May, Ruhl and Ellis began forming plans for Ruhl to come to Fort Worth to cut his first full-length. Ruhl has been here ever since.

The following is his story in his words.

*****

In October 2006, I got expelled from high school for the last time. I had been attending the Mississippi School for Math and Science, which was a public boarding school on the Mississippi University for Women campus. I had already accrued all kinds of infractions in my year there (to include drinking so heavily at a school event I was taken to the emergency room), and by the time I got caught cheating on a government test in October 2006, I was already on very thin ice. The academic dishonesty was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and I was expelled. When I got back to my father’s house, he was also at the end of his rope. He suggested I join the military, because as soon as I turned 18, he wanted me out of his house.

I guess I’ll start with the main traumatic experience. I was 17 when I joined the Navy out of Mississippi, and I contracted into the Navy to be a corpsman, which are the medical techs, so two years at Naval Hospital Pensacola working post-anesthesia, and then in late 2009, I was up for orders, and at that time, [the Navy was] taking all the corpsmen and all the medical personnel and pulling them over to 2nd Marine Division, because they were getting ready to troop-surge into Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom). In late 2009, I went to field med in Camp Johnson, North Carolina, which is part of Camp Lejeune, near Jacksonville. In March 2010, we left, and I was with 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines’ Bravo Company, which is an infantry battalion, and we went to Helmand Province, Afghanistan, and our area of operations was Musa Qala, which is north central Helmand.

I was 20 years old, going into Afghanistan with my unit. … We were there for seven months, but on May 17, 2010, I was on our little firebase — we built the firebase on a plateau — when we got a call that a patrol farther down the plateau had found an IED (Improvised Explosive Device). There were IEDs all over that end of the plateau, and we usually tried to not go down there … . It was usually ammonium nitrate, and it would have, you know, screws or ball bearings or something in it, some kind of shrapnel in there.

So, in that area, they were usually about 80-pound bombs, so they found one, and they called the firebase saying, you know, we need the EOD techs (Explosives Ordinance Disposal) to come out. Those were two guys that were stationed with us, and their job was to defuse these bombs. They were specially trained, kind of Special Forces in a way. They would go defuse these IEDs. They weren’t directly attached to us. We only met them when they got attached in Afghanistan, and so they weren’t necessarily in our unit. We just kind of knew them from going on patrols with them every once in a while.

On May 17, I punched out with 2nd Squad with the EOD guys. We walked down the plateau — the southeastern end of Sharma Shila ridge was the focus of all the IEDs found out there — and this happened all the time, a routine QRF (Quick Reaction Force) EOD patrol: Somebody finds an IED, we cordon it off, form a perimeter around it and provide outward security, and then the EOD techs would go in and usually put a charge on the IED and a timed detonator. They put a timer on it. You set the timer for two minutes or whatever, get the hell away from it, and blow it up, a controlled detonation.

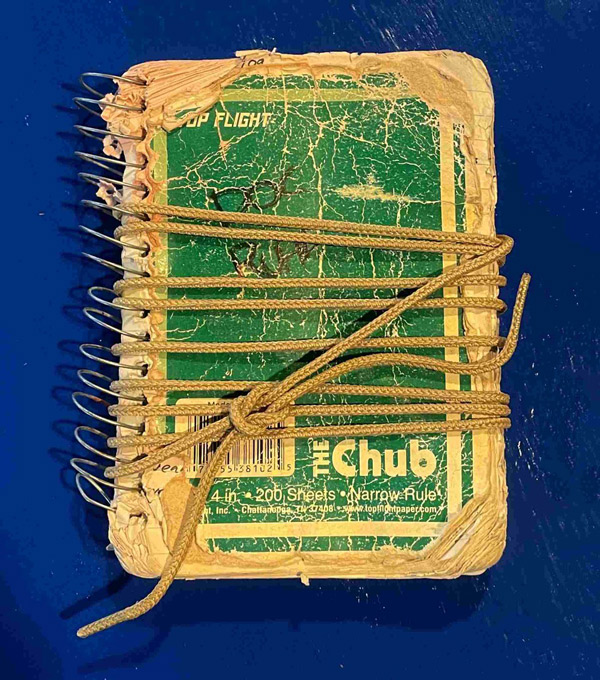

The two EOD techs were Sgt. William Ziervogel and Staff Sgt. Adam L. Perkins. We go down the plateau — the perimeter is already set around this IED. We get there, business as usual. I’m bumming a smoke off somebody. Perkins walked up to the IED — you could see where it had been marked and everything — and I’m sitting there talking to a friend of mine, and it went off, the explosion went off. I turn around — there’s just a massive dust cloud — and I remember seeing something solid flying through the air. Come to find out it was his left hand. I kept a journal, and this is a fragment of that day’s entry: ‘I saw Perkins clear the area with the metal detector and kneel down over the IED, and I looked away for half a second. Half a second later, a 155-mm British artillery shell encased in glass and metal scraps wired to a pressure-release detonator plate exploded less than two feet away from his face.’

I went into corpsman mode, you know? I was the medic, so I start running towards him, and he was maybe 40, 50 feet away from me? — and my buddy Sgt. Russell Lentz grabbed me, because they have to clear the area around the blast, because a lot of the time, what the Taliban would do was they would plant an IED, and they’d plant another one right next to it, so if the first one went off and got somebody, then the medic comes over, and they detonate the second one, because [the Taliban] really wanted to get us. They wanted to get the corpsmen.

At that point, the dust was clearing, and I could see Perkins on the ground. Ziervogel came over — we called him ‘Z’ — and swept the area around him. And I’ll never forget. Z was a big guy. He was lanky, but he was a big dude, but, I mean, we’re in the middle of a combat zone, and I couldn’t describe it any other way than just like a certain tenderness, that he just reached down and put his hand on Perkins, to check him.

From my journal: ‘As soon as I rolled him over, I could tell his left arm was amputated above the elbow, his bottom jaw was gone, his mouth was full of dirt. His nose was now just two holes in the center of his face. His right eye was gone. He’s bleeding heavily from his ears, and an area the size of my open hand was missing from the front of his skull, exposing the gray-white frontal lobe of his brain. When I rolled him over on his back, he moved just like the mannequins from field med. His legs were broken.’

I performed an emergency tracheotomy — I trached him. Whenever you’ve got massive facial trauma, you want to establish a patent airway, so I put a tourniquet on his left arm and started a crike (cricothyroidotomy) in his throat. At that point, I was calling in the 9 Line, which is the radio transmission to get a CasEvac (Casualty Evacuation). We were already calling it up when my superior back on the firebase told me to start CPR, which you do not do on the battlefield. Corpsman Ryan Miller was resisting that. I said, ‘Just do it.’ ‘A large shrapnel wound in the upper chest, a sucking chest wound, only it wasn’t sucking at all. His amputated arm wasn’t bleeding. I put a chest seal on the chest wound. … Miller is doing compressions. I’m breathing for him. His abdomen looked like a waterbed as he did compressions. … The blast liquefied all his internal organs. When I breathe for him in the tube, I get blood back in my mouth.’

CPR is to essentially keep someone’s heart going and to keep oxygen circulating until you can get an AED (Automated External Defibrillator, the ‘heart shocker machine’) on somebody, so you can get a shockable rhythm. CPR does no good on the battlefield, because once you start, you have to continue doing it, and in a combat setting, it’s not feasible. That’s all you’ll do until they get to a higher echelon of care.

We were getting shot at a little bit, but the Taliban are terrible shots — no training at all — so Miller and I started CPR on Perkins, and with the CPR I would get this really, really thready pulse in his neck. I’m sure it was just the CPR. I was checking his pulse in his carotid, because once you’ve lost a lot of blood and you start going into shock, your first palpable pulses you’re gonna lose are gonna be the farthest ones from the heart, so the carotid is the best to check if you’ve still got any pulse at all, and I think it was just the CPR that was pushing blood through his body, so we bandaged him up as best we could. We did everything we could.

Then a British CH47, a Chinook twin-rotor helicopter, came in and picked him up. And, typically, whenever you’re transporting a patient on a stretcher, you always go feet first. I’ll never forget, Miller and I carrying his body — he was dead — over to the helicopter, and the medic standing by the door — they’re all medics on these CasEvacs — had ‘Head First’ written on his hand and flashes his hand at me. We turn him around headfirst, get him on the bird, and they took him off.

From my journal: ‘When the bird got there, my patient turnover was simply, “No pulse, no respiration.” It took (Mark Allan Stevens, my senior line corpsman) telling me before I finally believed it — I did everything I could.’

We ended up finding some more of his body parts, boxed that up so it could be buried with him. I was given the honor of carrying those body parts in a box and putting it on a bird a couple of days later, and, man, it really … it really fucked with me for a long time. You know, he had a wife and kid, a young child. Here I am, 20 years old — by then, I was 21; I turned 21 in April in Afghanistan — and you know, I’m just thinking like, ‘Why the fuck would that guy die? I’ve got nobody. I don’t even have a fucking goldfish,’ you know?

This is a fragment of that day’s journal entry: ‘I didn’t know his first name, where he came from, or what he planned to do after the Marine Corps, but I still haven’t cleaned all his blood from my uniform, my gloves, my gear, my watch, my fingernails. He died today, and I watched it happen. Miller and I agreed there was nothing we could do.’

And come to find out after the fact, the IED that killed him was unique. It was a pressure-release IED, not the typical IED where you would step on a pressure plate. There had been probably a 15-pound rock on top of this thing, so when he knelt down and took that rock off the top, it went off, so he was kneeling over a 40- to 60-pound bomb when it went off. You know, I didn’t know him that well. We talked a couple of times, and that’s a small blessing, I suppose, to have not known him super-well, but at the same time, to be there when that happened was …

Courtesy Jon Ruhl

*****

I got out of the military in 2012, and the readily available camaraderie and the support system in the military had kept me pretty well together, but when I got out in January 2012? Man, I just went off the deep end. I fucking lost it. I was drinking extremely heavily. I was winding up in the hospital and arrested, like, all the time. I was out of control. And I remember — I say I remember, but it was a blackout — that I didn’t know how to process what I’d seen, what I’d been a part of, honestly. I didn’t know, like, why did I survive? Why was I there when that happened? Why wasn’t I able to do anything, you know? … I mean, it was a very horrible thing to see, a horrible thing to be around.

But it must’ve been in 2013, a friend of mine was being treated at Bethesda, Maryland, and I went to go see him. We had gone to Afghanistan together, and we must’ve gone to a bar, and I got totally plastered, and I vaguely remembered him dragging me back to wherever he was staying. I just remember crying my eyes out and calling for Perkins for some reason, which I think I did regularly in blackouts. I would relive this thing where I’m just screaming for him as if the bomb had just gone off, and I was standing there again — because that’s what happened when that bomb went off — and I started running toward where he was. I was yelling his name. I’d relive that in blackouts.

I just felt worthless and purposeless, and the medication that the VA (Veterans Affairs) gave me … I was seeing a psychiatrist at the Washington, D.C., VA, and he pretty much just followed a flow chart. I would tell him my symptoms, and he would say, ‘Oh, that symptom requires this medication,’ and I’d say, ‘I also feel like this,’ and they’d add another medication! They put me on, like, six medications in four months, and I felt crazier than I’ve ever felt in my whole life — and I probably wasn’t supposed to be drinking heavily on them and smoking a lot of weed — but I was just trying to get through the day.

It must’ve been May of 2015 when I booked a trip to Peru with this ayahuasca retreat. I was going down to do that because, honestly, I probably had this naïve thought that something I could take would fix me. I could take some drug, and it would fix what was going on. It’s funny because I had heard the reference to ayahuasca from a Father John Misty song (“I’m Writing a Novel”) and another from some show where a guy drinks some ayahuasca and has some big trip, so I started looking into it and was intrigued by it, and I thought I’d give this a shot, because the medication hadn’t really accomplished that much.

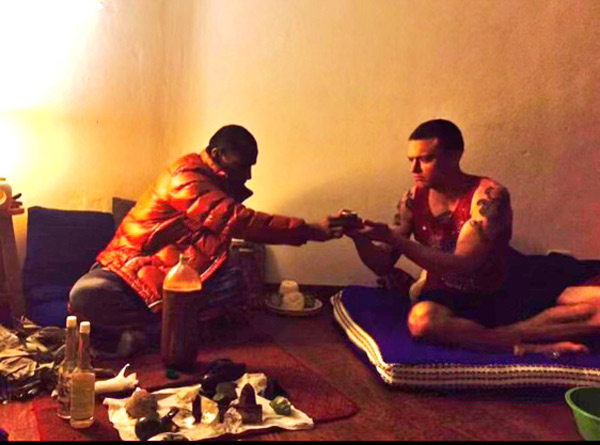

In 2015, I booked this trip down to Urabamba, Peru with a friend of mine, but the trip itself was facilitated by an Australian guy (Neils) and a French Moroccan girl (Sarah), and they were linked up with this Shipibo shaman from the Amazon. Urabamba is close to Cusco, and it’s pretty far from the Amazon, but the shaman, Gumé (Gumércindo), would come down, like, once a month and do a retreat.

*****

Ayahuasca, medicine, enrapture me fully! Help me by opening your beautiful world to me! You are also created by the god who created man! Reveal to me completely your medicine worlds! — Ayahuasca Song of the Shipibo

We first did a mescaline ceremony, a San Pedro ceremony, and, honestly, I was reading The Holotropic Mind by Stanislav Grof at the time, and I think I was trying to form this idea of what the trips were supposed to be like, so that honestly hurt me more than helped. It clouded the original experience of the psychedelic, so I didn’t really get anything until the third ayahuasca ceremony. I didn’t really get much out of the first ceremony. The second ceremony, I took two cups of the ayahuasca. My journal for that day says, ‘5-7-15: My second ayahuasca ceremony was another disappointment. I had a sensation of having a very large body and was floating in outer space. It felt great at the time, but it doesn’t have any bearing on the reasons I came here.’ They assured us that, even though you’re not feeling anything and you might not have a vision, just be confident, the ayahuasca is working.

Courtesy Jon Ruhl

There were only four ceremonies, spread out over 10 days. The San Pedro ceremony was on Day 2 or 3, and then the next day was an ayahuasca ceremony, and then the next day also, and the third day was a day off, so on the third ceremony, the shaman, Gumé, had told one of the facilitators that ‘this whole thing hinges on whether or not Jon has a vision, and so I want him to sit directly to my left for this ceremony, because that’s the way I move the energy around the room.’

Gumé had been kind of sick, and so for the first two ceremonies, he had just sat in one place in this outdoor ceremony room, which is dark. You do it at night because you want to lose as much unnecessary sensory input as possible, because during the ceremonies, Gumé sings his icaros, these songs to the spirits, bringing the spirits and moving the energy. You know, at the time I thought this was pretty far out there. ‘I’m just some dude from Mississippi who’s seen some fucked-up shit, but I’m down for it.’ ”

Gumé says, ‘You’re gonna sit directly to my left, and you’re gonna take two cups right off the bat,’ which I did. So, you just sit there in the dark with your eyes closed in kind of a meditative pose, and the beginning of the trip is this amazing … it’s like snakes endlessly moving over each other, but they’re kaleidoscopic, with geometric patterns. This is all happening in my mind. My eyes are closed, and Gumé is singing.

Historically, ayahuasca has been described as a feminine medicine. For centuries, it’s a woman in a white dress that shows up. Sure enough, a woman in a white dress comes and starts talking. ‘Isn’t it strange to have a body? Isn’t the body an odd thing when you think about it? I mean, it gets old. It gets sick. You know, it pisses. It shits and vomits. It breaks.’ And at this point, I’m like purging. I’m throwing up, which is a really good sign as far as the ceremony goes. It makes sense. It’s fitting. It’s this thing that you have to get out of you.

From my journal: ‘As I fell into a deep consciousness, I remembered to focus on my breathing and allow Aya (ayahuasca) to do her work. I found myself in a beautiful place, indescribably gorgeous with mountains changing colors, yellow meadows, and a sky that was simultaneously night and day. I became one with this place and felt my arms were tree trunks, my body a boulder, as I left my own human body.’

At this point, I was deep in the vision. I’m purging. I’m throwing up, and the woman in white is describing this thing, this body, and “isn’t it strange how people are hell-bent on killing other people’s bodies?’ And she’s tying this into combat and warfare and how the body is this vehicle. It’s this transient thing that bears less importance than another part of us.

It was about this time that the consciousness of Adam Perkins and I started to interact, and I can’t remember exactly how it started, but I was kind of talking with him like we’re talking right now, and I said, ‘I’m really trying hard to remember your face, because the face I remember, half of it was gone, and your eye was out of its socket. Your jaw was gone. … I’m trying to remember your face before that image was burned into my brain.’ He said, ‘You don’t need to do that. I don’t have a body anymore.’ I said, ‘Oh, well, that makes sense.’ He said, ‘I want you to know that when that bomb went off, I was still right there, looking down at my body in the condition it was in, and I saw you come over, and I saw the way that you worked to save me, and I saw the care and the love that you put into it.’ And he said, ‘I want you to know I made a choice. I made the choice to come here.’

Now, I didn’t describe the setting we were in. Earlier that day, I had hiked up Pumahuanca, this mountain in Urubamba — it’s a beautiful, beautiful mountain in the Andes. You hit this beautiful plateau, and you can just see for miles. You can see down into the valley where Urabamba is, and you can see across the desert, the high desert plateaus of the Andes … and it was like we were up there again, Perkins and I were up there, but it was like a Van Gogh painting, right? And it’s funny because off in the distance — keep in mind I can still hear Gumé singing his icaros — I look down the path a little ways from where Perkins and I are sitting and talking, and Gumé is in this full traditional Incan shaman’s dress and dancing while he’s singing his icaros. Now, he was too sick to dance during the first two ceremonies, but come to find out after the fact, he was dancing during the whole third ceremony, but I’ve got my eyes closed during this vision.

Perkins said, ‘I want you to know I made the decision. I could have gone back into my body and tried to eke out a couple of more years. My family would’ve seen me in the hospital like that. I would never have been able to do anything that I love again, and that would have been everybody’s memory of me, me and that broken body, and I decided not to go back into it. I decided to come up here instead.’

And the fact that it was his decision completely flipped a switch in my brain. I was like, ‘So, it wasn’t something I did?’ The older I get, the more I realize it’s not all about me! He said, ‘And up here, you know, I can lie down and sleep, or I can get up and walk,’ and he said, ‘Time doesn’t exist here.’

About this time, Aya comes back, the woman in the white dress, and she says, ‘It’s time to go.’ I looked at Perkins, and I said, ‘Do you want me to reach out to your family, tell them you’re OK or anything like that?’ He says, ‘No, they know already. I’ve already talked to them.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry. You’ll be here with me someday.’

*****

I came out of the trip immediately. Now, I’ve done a lot of drugs. I mean, I’m a recovered alcoholic, and I’ve done everything under the sun, from pain pills to meth, but I’ve never in my entire life done a drug where one second it’s active, the next second it’s gone. I came to, and I’m back in the maloca (a large circular hut, the ceremonial space used by the Shipibo people for the ceremony). Gumé had sat down again, and I was completely back in my body. I looked over at the Australian guy and the Moroccan girl, Neils and Sarah — they would facilitate, like if somebody’s having a really hard time, they would kind of comfort them and bring them back. They were sober for the experience, so they could help anybody that might need help. So, I lean over to them and whisper, ‘I’m gonna go smoke a cigarette.’ They said, ‘OK, be very quiet,’ so I tiptoe outside.

They sell these cigarettes down in the Andes, mapachos. You can buy, like, a 3-gallon bag of these hand-rolled, unfiltered cigarettes, jungle tobacco, absolutely delicious. And I light one of those, and I was just staring up at the stars, and it was like … this thing that had been eating me alive for years, how to come to grips with the death of that man, and Perkins himself describing it saying, ‘I had a choice, but thanks for trying — really, thank you, but I made the choice to come here’ — that absolutely shifted my perspective to where it needed to be. And he had told me, ‘Quit worrying about me. I’m fine. This is great up here. Don’t worry about me.’ And he reminded me that ‘you didn’t realize it, but you were pouring love into my soul.’

Journal entry, 6-5-17: ‘I came to see death differently as the body is accepted back into the Earth, as the soul is accepted and assimilated back into a universal consciousness, in which the individual maintains a certain identity while being a part of the divine spirit in whole and equal parts. So many things that my freewill mind is unable to comprehend on this plane, I came to know: that Perkins is in a beautiful, peaceful place, better off without his mortal form. I will never wear the memorial bracelet again’ — I have a bracelet with his death date and name on it — ‘knowing that he no longer needs anything from me, knowing that his memory is preserved and actively holding onto it was something I did for myself.’

Aya began closing my eyes to that plane, and I said to Perkins, ‘I can’t stay in this place much longer. I have to return to my body. ‘He replied, ‘You’ll be back here someday. You can come visit occasionally, but one day, you’ll come here to stay.’ It was breathtakingly, indescribably beautiful. My vision ended, and I woke up back in the maloca, and that was it. Aya had shown me all I needed to see that night.

Cara Merendino

*****

I’m outside smoking, and Neils and Sarah came out — they had been worried because I hadn’t had a vision for the last two ceremonies, and I described to them what I had just seen, and Sarah was just weeping. It was incredible to be in that vision. It was genuinely like my consciousness had been taken out of my body and taken somewhere.

I had spent years at that point trying to figure out a way to move past this: group therapy, medications … you know, if there had been a way for that to happen, if that solution had been able to be put together in my mind, because that’s what I wanted more than anything, but in that vision, I was shown something by some other being or something. It was really like having my consciousness blasted into outer space, into some kind of outer dimension, being shown something, and then my consciousness was just zapped back into my body, and all of a sudden, I was back on Earth.

Perkins’ death was the most traumatic thing that happened to me in Afghanistan. There were other violent things that happened. My friend Woodburn got shot, but he survived. My friend Miller got shot in the arm, but he ended up being fine. There was a guy, Cory Szucs, that got pretty badly banged up in a strike on a truck, and he ended up losing his left leg above the knee. And I was in a truck that got blown up by an IED — I was close to a lot of them that went off — but I had such a positive experience with the ayahuasca in South America that I venture to say I’ll partake of a ceremony like that again someday because it was such a powerful thing. I think that when the time is right, it will present itself to me again. I mean, it’s like two plants, right? You take the root of one plant and the leaves from another plant, and you make a tea, and you’re blasted to a different dimension. They would have to have been shown by the spirits how to do that.

Honestly, I almost want to say that these substances need some kind of facilitator, the shaman, that prescribes a specific amount of a certain substance and then guides you through it, because, obviously, I don’t think I would’ve had the powerful experience that I had with ayahuasca if there hadn’t been a shaman involved. So, I think that’s kind of a crucial aspect that most Americans unfortunately don’t realize.

I will say that since that experience in Peru, I’ve developed a deep respect for psychedelics, these substances that have such therapeutic value, and specifically natural psychedelics like ayahuasca, psilocybin, and San Pedro.

I’ve had some really beneficial experiences from psychedelics, and anytime I talk to somebody about it, I try to talk about it with an absolute respect and a kind of reverence for these sacred substances, ‘the flesh of the gods.’ You know, a big part of sobriety and working 12 Steps is a reliance on a power greater than ourselves, and through my psychedelic experiences, I’ve been given an understanding that really transcends religion and is able to easily exist outside of organized religious viewpoints, something that’s been with me and kind of taken care of me, in a way, and shown me some things, because, man, I wanted to die for a long time, and a lot of this journal was written in just really low, dark, alcohol, drug places.

And, finally, that’s another reason I’m kind of interested in doing ayahuasca again, because they really recommend cleansing before using, as in sobriety, and that’s probably why I didn’t get anything out of the first two ceremonies, because I was so blocked off with my alcoholism, because with alcoholism you just put everything in that bottle and shove it way down inside, but somehow, ayahuasca got past it.

A North Texas music historian, writer, and musician, William L. Williams is co-author of Metro Music (TCU Press), celebrating 100 years of North Texas music history, and a three-volume history of the Caravan of Dreams, available for free download at MetroMusicProject.com. Along with fellow ’60s musician-friends, he’s been researching, archiving, and covering North Texas music history since 2003. He is currently writing a series of essays on creativity, entheogens, and the mystical experience.