Two nearly 90-year-old stories came together in a polychrome sandstone retaining wall. Wearing a small, forgotten commemorative plaque, it faced the athletic field on the landmarked former W.C. Stripling High School campus in Fort Worth’s Arlington Heights. Wall and plaque were inseparable — from each other and from the life and labor and social history they represented.

In a third story’s ongoing 21st-century narrative, the massive structure got in the way of an architect’s plans. Even its stones were condemned — until their reprieve arrived via a forwarded email received on January 10.

*****

The phrase A SOUND MIND IN A SOUND BODY — inscribed on the cast-stone frieze atop Stripling’s gymnasium entrance in 1927 — conveys a translation from the works of the Roman poet Juvenal (c. 55-127 C.E.). Omitted from the frieze, the final words are: AND A BRAVE HEART.

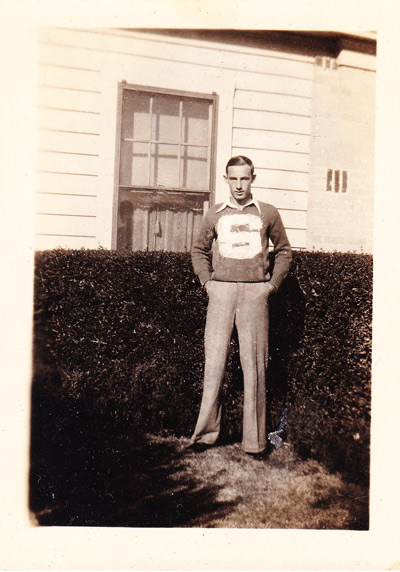

Health and life proved shockingly ephemeral for a beloved Stripling runner. Just a scratch, and Dale Benjamin Revercomb Jr. was gone within five months. Eleven more months passed, and an engraver created a plaque bearing Dale Jr.’s name and the years of his life for placement on the school’s new sandstone wall, a rustic, field-spanning, beautiful signifier of Great Depression hopes whose fate was determined only recently.

How did Revercomb die? The answer formed a cautionary tale. On the first Thursday in October 1933, track and field star Revercomb, a British immigrant’s son, sustained a minor scratch on his left elbow during football practice. He carried on without telling Coach Roscoe Minton and then fulfilled his halfback duties that evening under the arc lights at La Grave Field. There, the Stripling Yellow Jackets fought and lost to the formidable Mighty Mites (of 12 Mighty Orphans fame) from the Masonic Home of Texas.

The unattended abrasion led to a staph infection and then to pneumonia. Amputation of the left arm was considered. Not too long ago, Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist and Stripling alum Bud Kennedy surveyed long-ago wire service coverage of Revercomb’s decline, noting that “people nationwide were pulling for him.”

When recovery looked like a lost cause, the coach, team captain, and quarterback brought a football letter sweater to his bedside at home. Not long after their visit, the athlete descended into a coma and died on February 10, 1934.

Revercomb’s death was not the only significant Stripling-related loss at the time. One day earlier, Wesley Capers Stripling Sr., the department store founder after whom the school was named and who had funded its initial landscaping and plantings, died from arteriosclerosis at the age of 74. Funerals for the two men were scheduled for the same afternoon, with burials to follow in different sections of Greenwood Cemetery.

There was no room for 1,200 students inside First Presbyterian Church, where the elderly merchant had been a prominent member. They assembled for a separate, simultaneous service in their school auditorium at 2 p.m. on February 12.

Next came the Revercomb funeral at 3:30 p.m. at G.H. Connell Memorial Baptist Church. Undertakers at the Arlington Heights branch of Harveson & Cole Funeral Home had followed the 18-year-old’s wish to be buried in that honorary letter sweater. Six Yellow Jacket football squad members served as his pallbearers, and athletes and coaches from other local high schools joined his family and a large Stripling delegation. Pastor Shervert Hughes Frazier Sr. described a youth “clean in body, clean in heart, clean in thought” who “possessed mastery of self.” An account published by The North Adams Transcript — in the Massachusetts city where Dale’s mother and her family had lived after immigrating and before coming to Texas — included more praise from the pulpit: “The minister said he had never witnessed a more courageous fight than young Revercomb had waged during the many weeks of the illness.”

Traumatized, Doris Mae Aspin Revercomb ceased speaking of her firstborn child’s life or death. Although she and husband Dale Sr. established a memorial award for a best all-around Stripling student, no framed photographs, ribbons, or keepsakes were displayed in the family’s bungalow on West 7th Street.

Another ceremony — a double commemoration — followed one day in January 1935. People who loved Dale Jr. gathered in front of a new wall that stonemasons had completed in 1934. A simple bronze plaque was affixed to one column of the wall’s east stairway. That done, the athletic field was dedicated to the young man.

Dale’s surviving siblings, Edwin Francis and Wilfred “Wilcie” Herbert, followed him into sports. Edwin joined a junior minor league baseball team, Howell’s Hefties, who won the Fort Worth championship in 1935, with Wilcie as its mascot. Both advanced in varsity sports at Stripling, at the new Arlington Heights High School, and at TCU.

Edwin’s lifelong passion for golf would be chronicled in Dan Jenkins’ 2014 book His Ownself: A Semi-Memoir: “I put in the [Fort Worth Press] story that Ed was the coach at Parker Junior High in real life and he won the tournament by stiffing his wedge so close to the cups, his golf ball chewed on the flagsticks.”

When they had sons of their own, the Revercomb brothers shared Dale Jr.’s story with the three nephews who would never know him. Edwin told his elder son, namesake Dale Edwin, that he had never met a finer man than his late older brother. One day, when the time seemed right, Wilcie took his only son, Alan Leslie, along with Edwin’s younger son, Kyle David, to see the plaque and explain its significance.

Courtesy the Revercomb family

Something of Dale Jr. also came through in Wilcie’s 1996 Star-Telegram obituary: Wilcie “spent more time just teaching his son golf than many fathers spend with their kids in total. This forged a special bond between them. And the integrity [Alan] learned on the golf course carried over into everyday life.”

The first Revercomb Memorial Award, conferred along with a medal in May of 1935, went to Stripling senior Roy Edwin Snyder, who became a physician and surgeon, living to the age of 93.

*****

West of Where the West Begins, great ribbons of ferruginous sandstone (regionally named Palo Pinto) had formed between 323.2 and 298.9 million years before, creating part of the Pennsylvanian strata of the Carboniferous Period. (“Ferruginous,” borrowed from Latin, refers to the occurrence of rust coloring from iron oxide.) Nearby and abundant, stones in Palo Pinto and Parker counties had been harvested on a small scale since the late 19th century for building homes, courthouses, and boundary walls.

Those formations would prove equal to an unprecedented and unexpected demand for dimension stone during the Great Depression. “Just around the corner, there’s a rainbow in the sky,” promised Irving Berlin’s 1932 cheery-satirical “Let’s Have Another Cup of Coffee” (“one of the gentler anthems” of those hard times, in historian Lawrence Maslon’s opinion). As it turned out, some rainbows were earthly and earthy.

Huge sandstone-extraction orders would soon be placed. New quarries would open near railway tracks. Jobs would replace lost jobs. In Fort Worth, people who valued and needed city parks, public schools, and park-like neighborhood school campuses would number among the beneficiaries of public works programs that made use of those stones.

The FDR administration confronted the economic and humanitarian crisis immediately after the 32nd president’s first inauguration on March 4, 1933, with speed to match desperation. New Deal work programs began and — quickly — evolved.

Under the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Civil Works Administration (CWA) was established in November 1933. Its charge was to provide relief work for unemployed people through the coming winter, and, as the National Archives said, it “functioned simultaneously, and to some extent with the same personnel, with the Federal Emergency Relief Administration” (FERA). At state and local levels, the Texas Relief Administration was created to work with those two federal organizations, and the Fort Worth school board and the district’s landscaping director were also involved.

New Deal dollars activated as-yet-unfunded designs by Hare & Hare Landscape Architects of Kansas City, Missouri. Their vision for enhancement of Fort Worth parks and schoolgrounds would be made real. Stonemasons and unskilled laborers were hired, and Stripling’s campus — covering the entire long block of 2100 Clover Lane — was among the first scheduled for improvements.

Two months after Dale Jr.’s injury on the field, a landscaping team reported to the Stripling campus in December 1933. They came, in part, to level the sloping land just south of the building, and to establish asphalt-coated tennis and basketball courts there. That required a sturdy retaining wall.

Tons of sandstone arrived for the wall project. Stripling students, teachers, staff members, neighbors, and passersby saw the CWA signs and witnessed the facing, setting, and dressing of stone blocks to form the wall between the ball courts and the lower-level athletic field.

A separate and different type of wall was also crafted. At the corner of Thomas Place and El Campo Avenue, framing the southwest extremities of the field, you can still see and touch parts of the low boundary walls made from limestone rubble that laborers excavated at the site. Workers planted trees around the perimeter.

By mid-January 1934, the CWA had employed 4,263,644 people across the country. Although many protested, that agency was liquidated after only five months. The Stripling transformation was completed under FERA oversight before the newly formed Works Progress Administration (WPA) took over such projects in 1935.

*****

Mutantur omnia, nos et mutamur in illis. (All things are changed, and we are changed among them.) — Late Latin Proverb

In a familiar scenario, someone comes for a significant chunk of the past, wielding an approved hammer. Landmark status fails to protect an element of a community’s built history. Due-diligence communication proves challenging when institutional and business protocols dictate nonresponse and delayed response. Even salvaging stones from a wall becomes a bureaucratic obstacle course.

Fast-forwarding through decades: Stripling became a junior high school after completion of the new (second) Arlington Heights High School in 1937. In the post-WWII era, more and more early-adolescent Baby Boomers crowded inside — leading to extensions of the original back wings farther to the west in 1955 and 1958. A portable wooden classroom “shack” or two sojourned in part of the back courtyard in the 1960s, to be bumped away by a windowless Lego-block of a second gym for what had become a middle school. At some point, Stripling’s multiple-pane, double-hung, sashed wood windows were scrapped, replaced with dual-pane, mostly masked windows.

Courtesy the Billy W. Sills Center for Archives, Fort Worth Independent School District

Stripling’s historical value was asserted twice in 1988’s Tarrant County Historic Resources Survey: North Side, West Side, and Westover Hills, a volume of a series published by the Historic Preservation Council for Tarrant County. In addition to providing an illustrated history of the school, the council recommended formation of historic districts, conservation districts, and thematic groups — with a proposal that Stripling and other local pre-WWII school buildings form the Public Schools National Register Thematic Group. Introducing and narrating the series, archivist, historian, and author Carol Roark observed that “Fort Worth is fortunate to possess an unusually large collection of older school buildings in relatively intact condition.”

Sought-after architects designed many of those structures. Wiley Gulick Clarkson Sr. chose an eclectic Georgian Revival style for Stripling, and Kindred Henry Muse built it. Among Clarkson’s extant works are the Sinclair Building, Harris Hospital, the former W.I. Cook Memorial Hospital, First (United) Methodist Church, the Masonic Temple, and the Mary Couts Burnett Library at TCU. Contractor Muse also built a gymnasium for TCU, the South Side Masonic Lodge, and Millers Mutual Fire Insurance Building in the 1920s. A registered graduate architect, James Dent Vowell, designed the two 1950s additions to the back of the Stripling building.

In 2001, the city’s planning department published Eight Decades of School Construction: Historic Resources of the Fort Worth Independent School District, 1892-1961 funded partially by a grant from the National Park Service as administered by the Texas Historical Commission. Its author and consultant, historian Susan Allen Kline, credited students for guarding historical integrity.

“It should be noted,” she wrote, “that the designation applications for Stripling [Middle School] and Trimble [Technical High School] were prepared by students of those schools.”

The Stripling students’ efforts were rewarded. Both building and campus gained city landmark status — together — in 2002. Addressing adaptation of old buildings, the city planning staff said, “Under the 1999 bond program, historic schools are receiving technological and [Americans with Disabilities] upgrades, proving that they can be adapted to meet modern needs. Some are receiving additions that respect the historic character of the original school. Within the past five years, three former school buildings were adapted to other uses in ways that preserved character-defining features while demonstrating that new uses can be found for surplus schools.”

*****

School districts tend to value modernity over retrofitting for the sake of historic preservation. A quick Google search using the subject “school district demolishes landmark” brings forth stories from Arkansas, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Oregon, New York, and elsewhere across the country.

Witness demographer Bob Templeton’s recent statement about projected local school closures in response to declining enrollment. “That sometimes will cause a spark of return,” he has said. “When they see the new buildings and they see the improvements, it can create excitement to get back to the neighborhood public school.”

Templeton, from the housing-market research firm Zonda who has consulted with the Fort Worth school district in the past, sees this as a way for the district to consider building replacement campuses instead of maintaining old buildings.

Mike Naughton, executive director for facility planning and geographic system analysis for the FWISD, expressed appreciation for history in an interview last summer. He has been supportive of the district’s Billy W. Sills Center for Archives, which was recently allotted prominent space in the new administration and service center on Camp Bowie Boulevard.

A needs assessment study of Stripling preceded its inclusion in school bond-funded changes. “The intent was to come up with a concept plan,” Naughton said. Concerns noted in the study included classroom size, location of offices, and mechanical and technological installations. Naughton elaborated on government-mandated standards for classroom size. The Texas Education Agency’s Rules for School Safety and Facilities Standards, which took effect November 1, 2021, require larger classrooms. Earlier, he said, the requirement was 675 square feet, but it has increased to 800-900 square feet. “In renovating [to increase space], we generally have to remove walls.”

Explaining a proposed $1.5 billion school bond issue to WFAA in October 2021, former superintendent Kent Scribner said, “We do believe infrastructure is equity. Infrastructure is equal opportunity, and we want all of our students playing on an even playing field across Fort Worth but also when we compare ourselves to our suburban districts. Our students deserve adequate facilities.”

Paradoxically, even as Stripling expands, a Fort Worth Report analysis from last November listed Stripling among local schools with greater capacity than enrollment. Superintendent Angélica Ramsey and her administrative staff are confronting the general decline in enrollment. While awaiting completion of a master plan — and time to study it — she has said that they will not issue any school-closure proposals.

After the bond issue passed, it was Stripling’s turn for a major addition, bringing drastic change to its landscape and to the historic symmetry of the building’s façade. FWISD contracted with Hahnfeld Hoffer Stanford for the design of a new wing, security fencing, and replacement windows. David Stanford, one of the firm’s principals, designed the building, and Janie Garner was named project manager for the addition and renovation project. (In November 2023, Grace Hebert Curtis Architects acquired the firm and renamed it Hahnfeld Hoffer Stanford, a GHC Studio. Garner’s title was elevated to that of senior architect.)

The new wing will be built to the south of the original south wing, slightly set back on the lot, and its front doors will become the school’s new main entrance. Administrative offices will relocate to the new structure’s ground floor. It will feature large classrooms, built-in technological connections, and improved access for persons with disabilities.

Offering the illusion of tradition, the firm also brought window plans to the city’s preservation staff and the Historic and Cultural Landmarks Commission (HCLC). They called for installation of historical replication offset fixed windows, manufactured by Manko Window Systems, a Manhattan, Kansas-headquartered company that offers windows that can be opened, but Garner explained that the fixed-window version was chosen for its greater strength.

Since the school had already been stripped of its original wood windows, the substitute materials may be used to meet National Park Service/National Register of Historic Places preservation profiles. This can only be done if the original windows are no longer in place or are beyond repair. Ironically, then, the earlier replacements made possible the later use of pre-finished aluminum surfaces and insulation with polyamide strut thermal separators.

The replication windows will bring three benefits: full light, insulation, and traditional appearance. They, too, will require maintenance — as did the lost historic windows. Similar amends were made at Arlington Heights High School, which had also undergone a round of insensitive window treatments.

*****

Unlike the larger and deeper campus of Arlington Heights, Stripling has a shallow backyard. The space selected for the desired new wing lay to the south. A faculty parking lot occupies much of the land to the north.

The new structure will swallow the tennis and basketball courts. Only the basketball court will be relocated. Self-guided exercise stations installed in one of the court areas are going away. By design, excavation for the new building required a space too wide to permit the 1934 retaining wall to stand.

Asked if a narrower wing could have been designed, Garner said no. Asked if an inscription would appear over the new wing’s Clover Lane entrance — as passages advocating physical and mental health and an educated democracy were selected in 1927 for the gymnasium and auditorium entrances — she said no.

The project architect approached the city’s HCLC, presenting district-approved plans for Stripling in January 2023. The wall was neither mentioned nor deliberated at staff or commission levels “as far as I know,” said Historic Preservation Officer Lorelei Willett.

I learned of the wall’s fate during the commission’s May 2023 meeting. My request to query or comment was declined for legal reasons, as I had registered to speak on another case (representing my employer). A staff member told me that I might engage with the architects outside council chambers after the commission moved on to the next case. During that conversation, I learned that the architects knew nothing of the plaque. They promised to remove it and store it in a safe place.

Returning to City Hall in July, the next time the case was on the HCLC agenda, I was allowed to speak, having registered in advance to comment about Stripling. The brief presentation concluded:

If there is no will on your part to save it, or no way, I ask that you require the careful dismantling of the stones, for re-purposing, and that the architects design and build a structure (selecting the best salvaged stones) on the campus — perhaps in that grassy northeast corner of the field nearest the place where the plaque was placed 88 years ago — with a multi-language narrative about the fallen athlete, the public works programs, and the dedicated field. I ask that all parties involved find a way to keep history and memory at 2100 Clover Lane.

Archivist Lenna Recer of the Billy W. Sills Center for Archives had indicated that, if the plaque was not wanted at the school after the wall’s demolition, it would be welcomed into the school district’s historical collection. Garner wrote that she would design a few small structures so that one might be selected and constructed (as I had suggested) using some of the stones from the wall to provide a new home for the Revercomb plaque. Stripling Principal Amy Chritian stated that she was interested in keeping the plaque at the school. Later last summer, Chritian said she had heard that one design was for a sandstone bench.

Willett confirmed in a July 2023 interview that both the Stripling building and the entire campus are landmarked. Asked why the wall was not protected, given its inclusion in the landmark status, she said, “This happens even with houses in our historic districts. Our focus was on the school itself and how that addition was attaching to the school.”

Dealing with such issues, she said, “can be hard, because not everything can be preserved as we might like.”

One point made during the interview might lead future applicants for landmark status to seek additional protective designations for public-works elements that are, themselves, historic. Willett explained that “to our knowledge, the wall is not a designated piece.”

In what French engineer Jean Kerisel called the “battle with earth,” builders of retaining walls must anticipate the forces that will act on what they construct: the wall’s own weight, lateral earth pressure (from the soil they retain), loads on top of that soil, water, vibration, and changing humidity. Modern pressure — from institutions’ decisions about a wall like Stripling’s — is another.

*****

After addressing the commissioners, I met for a second time with the architects, outside the council chambers, offering to try and find a stone-reclamation specialist. When and if I found one, I said, I would inform them.

After much searching and many referrals, a veteran stone specialist responded in the fall of 2023. Jason Reinhold of Cincinnati, Ohio, is a stonemason, stone reclaimer, and natural stone consultant who helps clients choose materials for their jobs. During a business trip to Texas, he detoured from Dallas to Fort Worth in November to examine the Stripling wall. He met with Bob Byers, executive vice-president of the Fort Worth Botanic Garden; Brent Rowan Hyder, then chair of the Tarrant County Historical Commission, custodian of the city’s displaced stone Frenchman’s Well, and local preservationist and adaptive restorer; and Bob Lukeman, a photographer who had, in that season, begun visually documenting the wall and a visit by two of Dale B. Revercomb Jr.’s nephews, who had come in October to pay their respects.

Byers also assessed the stones, confirmed their Palo Pinto identity, and indicated that the garden would adopt the majority — provided it could arrange to store them. Learning that the Revercomb family had requested some of the stones, both Reinhold and Byers said that they would work with them and with Garner, setting aside stones she would select for a new, small memorial. Reinhold promised to detach the plaque with care. Byers, soon afterwards, obtained permission from the Park & Recreation Department to place the stones on a city-owned storage lot elsewhere in Fort Worth.

Reinhold, who seeks more Texas clients interested in his salvaged-stone inventory and masonry skills, made an extraordinary offer. Standing near the wall with Byers, Hyder, and Lukeman on the Friday evening before Thanksgiving, he proposed to return with an assistant, professionally dismantle the sandstones, and truck them to the storage lot gratis.

My first two messages to Garner about Reinhold’s offer went unanswered. After receiving a third one, she wrote to explain.

I have forwarded your past emails on to the owner’s representative for FWISD. FWISD has changed leadership, and they still have not sent me their final decision as to how best to incorporate the plaque and/or stone. We have designed several options for them. Additionally, we have called for a certain square footage of the stone to be salvaged.

We do not contract with the demolition contractor. That is the responsibility of the general contractor, and I do not know who they are set to contract with for that work or how much of the demolition cost is due to the wall demolition.

Additionally, I have been instructed by FWISD’s owner’s representative to not communicate regarding this until they make their decision. I am just as anxious as you are to learn what they decide, but it is entirely out of my hands.

Requested basic school-district timeline information was also not forthcoming, but I pieced parts together from other sources. A staff member who answered the main telephone number for the district said she did not know the name of the general contractor or the telephone or fax number for the contractor’s office. I obtained, printed, and hand delivered insurance documentation and professional background information for Reinhold to the administrative offices. Kevin Lynch, the FWISD trustee representing the district encompassing Stripling, did not respond to my twice-sent email asking for his support. A district staff member then forwarded it to him in case the first two had landed in a spam folder, but Lynch did not reply.

In early January 2024, Reinhold heard from Nate Moser, an owner’s representative who works with PROCEDEO, the district’s general contractor for the 2021 bond-funded capital improvement program, and with general contractor SEDALCO. It seemed that they might allow Reinhold to remove the stones from the wall. I wrote to the representative but received no answer at that point. On January 9, Moser again contacted Reinhold to confirm permission. Reinhold called and forwarded the news to me on January 10.

It is a long haul from Cincinnati to Cowtown. Reinhold requested assistance with basic lodging for a few days. He also asked for help finding access to a rubber-track skid loader with a set of forks and a bucket since he could not carry his own Bobcat 979 miles and back without damaging his truck trailer.

Initial efforts to find someone with a vacant, habitable space to host two men and a well-behaved dog and with permission to park the truck and trailer on the street failed. Charles Murphy, active member of the Arlington Heights Neighborhood Association (AHNA), made many inquiries. Christina Patoski, past president of the AHNA, advised me to appeal to nonprofits and foundations. One local nonprofit submitted a grant request — on Reinhold’s behalf — to a grantmaking group that has not announced a decision. The Botanic Garden administrator committed to securing use of the needed machinery.

Moser had to wait for a demolition permit from the city. Reinhold had planned to be available in early February, but Moser could not signal to him to head south until the delayed permit came through. When it did, in March, illness prevented the stonemason from leaving immediately, but he arrived in the late afternoon of March 18.

*****

Reinhold drove first to the campus then found lodging. The next morning, he drove to meet his assistant, José García, also of Cincinnati, at DFW airport. Reinhold rented equipment on his own to expedite matters. The two worked day and night from March 19 through March 21, salvaging 30 tons — about 80% of the historic materials — from the wall, loading them into metal cages and layering most with cardboard. On the last day, they extracted about 100 more sandstones from a related section along part of Clover Lane — those not already enclosed within the contractors’ fencing. Reinhold said Moser and the SEDALCO site superintendent, Mike Brown, were very accommodating.

Describing the CWA stonemasons’ workmanship, Reinhold said, “it was true hand-cut/hammer-dressed ‘snecked rubble’ — a random resisting pattern of squared and rectangular-shaped stones installed in a two-stones-over-one-stone pattern, with the sneck stone being the small square stone that breaks the pattern up. The mortar joints were tight and consistent, and all the stones were installed level.”

The Botanic Garden’s Byers arranged for transport of the stones away from the campus, overseen by Darrell Satchell, the garden’s trades and security manager. The workers transferred them onto 13 pallets. That additional assistance freed the volunteers to continue their labor. The city’s earlier permission to use a service center lot was withdrawn, so the stones traveled to a section of land the Botanic Garden has leased from the forestry division.

By the time the work was done, Reinhold had covered fuel, lodging, and machine-rental costs, as well as his assistant’s airfare. He had also subtracted days from his own work in Cincinnati and elsewhere.

During a conversation at the site, on the last day of stone reclamation work, I learned that the plans to build a bench or one of the other small structures that Janie Garner had designed — faced with stones she would select from the wall as the plaque’s new home — might have been scrapped by the district.

As a final blow to history and craftsmanship, the plans call for a replacement retaining wall to be built between the new wing and the athletic field. The possible destination for the plaque, I was told, is the new concrete wall, with cast-stone framing.

It was time to write to the project architect, requesting to see her designs; to an administrator, asking for reconsideration; and, perhaps, it was time to look for a local stonemason willing to create that smaller monument facing the field — with permission from the district and contractor.

On March 26, the project architect wrote, “I am not comfortable putting those out for public consumption, especially since they were rejected by the [school] district. Kellie Spencer has been very clear that she just wants a simple installation on the new building. … If the district changes their mind about plans for the plaque, we will certainly let you know.”

Spencer responded later that day. “We are evaluating all options and are open to your suggestions.”

I repeated my suggestion about the stone-bench choice.

It seemed, then, that the discarded past might yet find a place of honor on that dedicated field.

*****

When your children ask in time to come, “What do those stones mean to you?” — from Joshua 4:6

New Deal preservationists have been preaching — to the choir and to others with different priorities –– for decades. The nightmarish context of the Great Depression and the existential and morale-lifting benefits of public works programs often dominate their narratives. Others have focused on the aesthetics: distinctive designs, craftsmanship, quality, and character of the works. All testify to their significance.

In 1964, when those programs’ built legacies were only three decades old, John B. McClung, then a graduate student enrolled in one of Ben Procter’s New Deal history seminars at TCU, researched Fort Worth’s openness to landscaping as part of urban planning and improvement and wrote about it.

Here visionaries had … outlined projects which lacked only needed funds to be realized. With practically no wasted time or motion, the WPA [and, before it, the CWA] went to work. Although the agency engaged in many worthwhile endeavors in Fort Worth, it was to the public schools that it made its most lasting contribution.

Two decades later, Phoebe Cutler wrote of “the pervasive and often powerful ways the Depression inscribed itself upon the landscape” in her 1985 book The Public Landscape of the New Deal. Having revisited Cutler’s volume 30 years after its publication, historical geographer Gray Brechin reflected, “It suddenly made visible to me the continent-spanning matrix of creations that my parents’ generation built but neglected to mention because few were aware of what [that generation] had accomplished working their way out of the Great Depression.”

David Baird, another historian researching this region in 1987, introduced his final report on then-extant WPA works in Oklahoma, calling them major cultural resources and explaining their worth.

Among other things, they were mute reminders of the emotional distress and physical pain many Oklahomans suffered during the 1930s and of an enlightened relief effort by the federal government that alleviated much of the suffering. Many who benefited from the agency saw its work as the margin between life and death, starvation and survival, despair and hope. Each structure built by the WPA, therefore, constituted a symbol of the struggle and the victory experienced by most of Oklahoma’s poor during the Great Depression.

In her essay “The Extraordinary Legacy of Hare & Hare in Fort Worth” — published online in 2018 by The Cultural Landscape Foundation — Susan Allen Kline mentioned that the designers’ oversight of school landscaping was done “in concert with park projects.” Work at 64 schools, she wrote, including five new high schools, “varied from new sidewalks to large amphitheaters. Although much of the work has been lost to building and parking lot expansions, rustic stone or concrete elements, such as terraces and retaining walls, remain at many schools, as do hundreds of trees.”

Besides documenting New Deal contributions and advocating for their preservation, Kline has successfully researched and authored many historical marker applications in and beyond Fort Worth and Texas. In her book Fort Worth Parks (a collaboration with Fort Worth Parks and Community Services), she contributed an illustrated narrative of local park history through Arcadia Publishing’s Images of America series in 2010. With her husband, Steven Kline, she has collaborated on illustrated essays for the database of The Living New Deal, a nonprofit working with historians, educators, archivists, and preservation groups (including the National Trust for Historic Preservation).

In May 2023, Libby Barker Willis — historian, preservationist, and author who served as the first director (1984-1996) of the Texas/New Mexico Field Office of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (later the Southwest Office of the National Trust), met with Kellie Spencer and other school administrators and brought copies of the city’s historic schools survey. Her timing was perfect. It was Spencer’s first day on the job. Regarding the wall and plaque, Willis recalls, “I checked with the district and learned that the memorial plaque at Stripling will be saved and that they will find a place for it at the school.”

Spencer would, at a later date, introduce herself to me, offering to be helpful, and she responded to questions I sent her.

The Living New Deal’s director, Richard Walker, voiced concern about the Stripling Wall a month after Willis visited Spencer. Walker, emeritus professor of geography at the University of California-Berkeley, wrote in June to Fort Worth’s historic preservation officer and the landmarks commissioners.

Tens of thousands of New Deal works are still extant and serving the American public, but many are in jeopardy of loss or destruction. People frequently contact us for help when these buildings, parks, structures, or artworks are threatened, given that the Living New Deal is known around the country as an information clearinghouse. … We have become aware that a site of New Deal provenance in your care is endangered. The sandstone wall on the Stripling Middle School campus … is apparently doomed by plans to expand the school.

We urge that the plans be modified to allow this piece of New Deal heritage and local history to be preserved, if possible.

After his work was done in Fort Worth, Jason Reinhold sent a text message from the road on April 8.

When I first met with you guys at the wall before Thanksgiving, I walked the wall and told your group how special the workmanship was, on the stonework. …

It was my idea to come salvage the wall and gift it back to the community of Fort Worth, where it was originally built, and the Botanic Garden would be a good fit.

My message to all of Texas is to save your architectural history and, at the minimum, recycle it when it has to be torn down.

Saving the architectural DNA of our ancestors is important.

*****

One sunny Saturday in October 2023, standing before the wall with brother Kyle, Dale Revercomb considered the possibility that a stone specialist might be allowed to rescue the plaque and the sandstone blocks.

“I would like to have some of those stones,” Dale said.

Later, his brother and their cousin Alan indicated the same desire.

In the case of the Stripling wall, months were spent on an end-stage scramble to — at least — prevent the crushing and trashing of its historic materials. Bringing together a stone specialist, an enlightened park administrator, and an institution that might or might not allow careful removal of stones finally worked.

Susan Allen Kline, Jerre Tracy, Bob Lukeman, Christina Patoski, Lenna Recer, Pamela Woodson, and Peggy Perazzo helped immeasurably. Libby Willis, Brent Hyder, Ted Gupton, Dale Edwin Revercomb — and others — enriched the research and the effort.

Nate Moser’s messages carried good news. Still, only the detached stones and the bronze rectangle now remain of something built to last and something making visible the name and years of a person’s life.

Photo courtesy of Jason Reinhold

Might the district turn to other local campuses and design away their New Deal structures and features? Preservationists already check agendas and address boards, planning administrators, and commissions. Historic Fort Worth, led by Executive Director Jerre Tracy, issues an annual list of endangered places. Without public discussion of how a wall became expendable, that element nearly escaped notice. Anyone can organize and speak in advance of demolition votes, but the devils in the details can elude public attention.

The Fort Worth Botanic Garden now becomes both refuge and repository for the dismantled Stripling stones. Their use as replacements for damaged garden stones, and for compatible new stonemasonry, will reunite historically and materially related stones. Without Byers and Reinhold, there would have been no way to save them. As Kline wrote, all features within the Municipal Rose Garden “were unified by the use of rough-faced Palo Pinto sandstone. … The rustic nature of the stone contrasted with the formality of the rose beds.”

The Stripling wall could not remain intact once three entities had approved plans for an additional building. Had the retaining wall been designated as a special feature within the landmarked campus, it might have been spared. What will the district and city decide if demolition of the essential sandstone terrace at North Hi-Mount Elementary School should be ordered? That school, too, is landmarked, but the Stripling outcome gives cause for concern.

When addressing the Fort Worth school board in late January, I exceeded my three minutes. Dale Revercomb, in attendance and having also registered to speak, graciously devoted his three minutes to delivering the rest of my remarks, concluding, “Next time, please don’t allow a situation in which all the keepers of history can do is ask permission to carry away the stones.”

Author, historian, and preservationist Juliet George is a W.C. Stripling Junior High School alumna and lives two blocks from the Stripling campus with her husband.

This column reflects the opinions and fact-gathering of the author(s) and only the author(s) and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. He will gently edit it for clarity and concision.