The New York Times’ 2020 series of feature obituaries, “Overlooked,” was primarily devoted to women and “people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported” in the publication. It was an ambitious project and one that Texas itself, as a state and a society, would arguably do well to replicate. Especially since a Texas woman named Jovita Idar was one of the series’ most compelling figures, and, on August 15, 2023, she became the second Latina and first Tejana to be featured on United States currency.

Jovita Idar’s face now graces the unfrumpy side of American quarters, and her presence is wildly original and artistic. On the flipside, George Washington appears more and more irritated by the usual oxymoron that undermines so much of our legal tinder: “LIBERTY” in large all caps up top and an arguably contradictory, monotheistic “IN GOD WE TRUST” smaller and left adjacent. Idar’s reverse appearance incorporates her chief cause, “MEXICAN AMERICAN RIGHTS”; her primary callings, “JOURNALISTA” and “TEACHER”; and the names of the publications where she championed Washington’s liberty in the face of Anglocentric injustice.

The “Overlooked” story on Idar in the New York Times was particularly intriguing to me because I had stumbled onto reports mentioning her family years before and, at first, didn’t make the connection. When I started researching her for another story, I recalled the original link. I discovered that something was missed or “overlooked” in all the new reporting and most of the scholarship.

Idar was born in Laredo on September 7, 1885. Her father, Nicasio Idar, was born in Port Isabel. Nicasio’s father was a Portuguese sailor who was rarely around and, according to Idar’s youngest brother, Aquilino (in a 1984 interview), Nicasio’s mother “sold” him to some cowboys for a year of work in Oklahoma when he was a teenager. He then got a job in the Nuevo Laredo railyards and worked as a yardmaster for 20 years. Nicasio met Idar’s mother, Jovita Vivero, of San Luis Potosi, in Rio Grande City, and they married. They had 13 children. Three died at birth, and one didn’t survive childhood. Jovita Idar was the second eldest. Nicasio had done fairly well and settled in Laredo, where in the mid-1890s he founded El Partido Independiente de Laredo to help Mexican and Mexican Americans there organize politically. By 1896, he was elected a Justice of the Peace. Nicasio and his wife’s children were raised with the relative privilege of la gente decente citizenry, and he placed a special emphasis on education and public service. Aquilino has said his father often discussed these matters with them.

Out in the yard, my father used to sit right there, and all of us — seven brothers and two sisters — used to form a circle around him. And he would talk to us about Mexicans, about Mexican Americans; how to fight for the Mexican people; what to do for the Mexican people. How to think. Don’t let anybody tell you how to think, because you are a freethinker. You are standing on the face of the earth on your own two feet. So use your own brain to work your way up in any situation. He said, “You don’t depend on anybody to tell you that you’re going to heaven, to paradise, or this and that. You’re gonna stay here until you die.”

Idar was able to attend the Laredo Seminary (later known as the Holding Institute), founded just three years earlier by the Methodist Episcopal Church.

From here in examinations of Idar’s life, most narratives — including the Times’ “Overlooked” account — jump to her father’s activism and his work as the editor and publisher of La Crónica, a local Spanish newspaper, but there was more to Nicasio’s progressive work. It included membership in Mexican-Tejano social and fraternal orders in the Rio Grande Valley, including the Masonic-structured Gran Concilo de la Orden Caballeros de Honor, of which Nicasio was the Laredo lodge secretary. And Crónica articles reporting on the lodge parroted Nicasio’s views. One from December 17, 1910, titled “Excitativa Del Gran Concilio de La Orden Caballeros de Honor a La Raza Mexicana,” is almost striking for its candor.

It is not possible … to attain respectability, trust, and protection within the American nation, if we ourselves do not have this with our co-nationals; if we believe that the Mexicans are unworthy of our association with them, of us joining their associations, we should not expect that the Americans would gladly receive us in theirs. If we do not have trust in the men of our own race, how can we expect other races to have trust in us?

As Gabriela González puts it in Redeeming La Raza: Transborder Modernity, Race, Respectability, and Rights (2018), the article “critiqued the divisions among Méxicano-Tejanos, particularly the selfish shortsightedness of the comfortable class for their lack of loyalty to the group and their lack of respect for Mexicans of modest means.”

After Idar’s graduation and attainment of a teaching certificate, she worked as a teacher in Los Ojuelos, a small community between Laredo and Hebbronville, but she was discouraged by the conditions and school facilities in the community and reportedly resigned, opting to work with her father and two of her brothers, Clemente and Eduardo, at La Crónica. In Crucible of Struggle: A History of Mexican Americans from Colonial Times to the Present Era (2011), Zaragosa Vargas notes the ways “the Idar family sounded off against separatist and inferior housing and schools, the abysmal conditions faced by Tejano workers that took on the visage of peonage, and the gross violations of Tejano civil rights” in the pages of La Crónica. And this, at a time when, as the Times’ “Overlooked” story describes it, “Laws of the Jim Crow era enforcing racial segregation also limited the rights of Mexican Americans in South Texas (they are often referred to by scholars today as ‘Juan Crow’ laws). Signs saying ‘No Negroes, Mexicans or dogs allowed’ were common in restaurants and stores. Law enforcement officers frequently intimidated or abused Mexican-American residents, and the schools they were sent to were underfunded and often inadequate. Speaking Spanish in public was discouraged.”

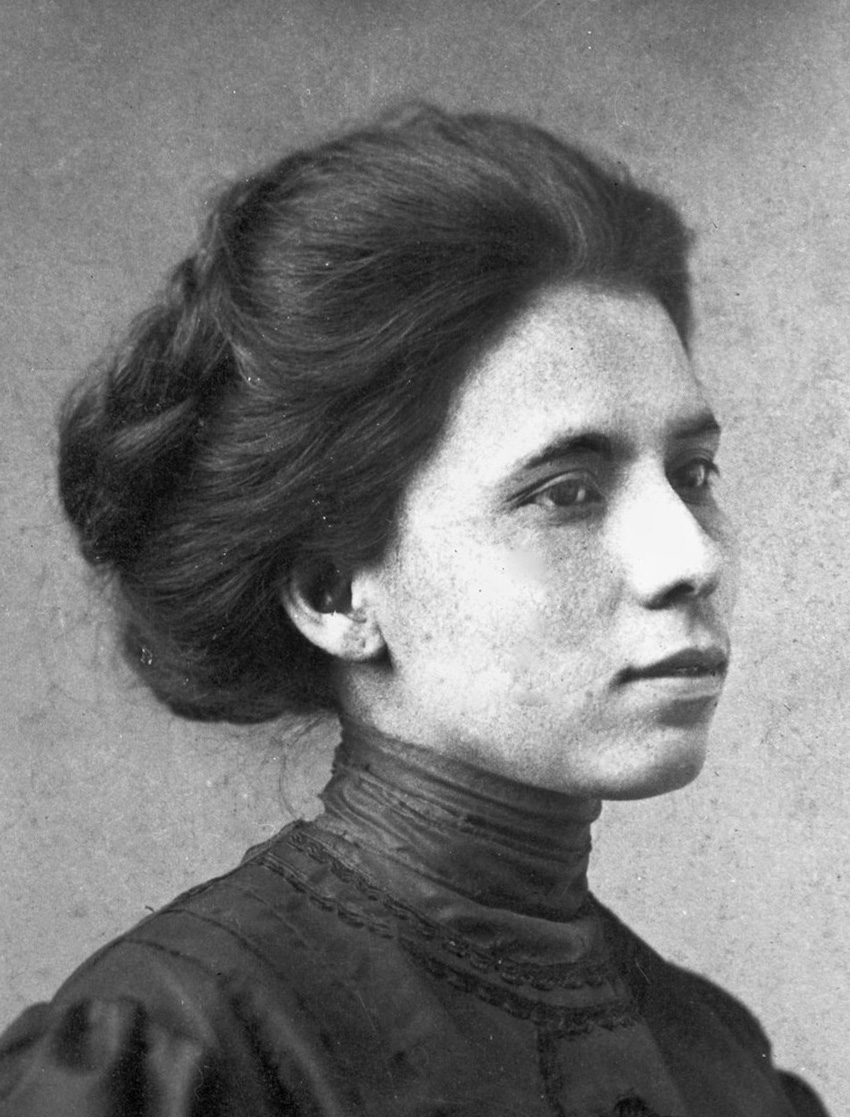

Wikimedia Commons

*****

Idar, herself, was particularly compelling. Often composing diatribes under pen names like “Ave Negra” (Spanish for “Blackbird”) or “Astraea” (the Greek goddess of justice), she tirelessly advocated for Mexican Americans and, particularly, women, asserting that they should educate themselves and not acquiesce to lives of subservience to men or, for that matter, the patriarchal Catholic Church. For La Crónica, it verged on a crusade. The publication’s writers openly blamed religious fanaticism for Mexico’s staggering illiteracy rate, noting that “83% [of the Mexican Republic] are illiterates who vegetate like pariahs, unconscious of their existence, and ignorant of their rights and duties as of a republic that proclaims to figure in the vanguard of the most cultured and powerful nations on earth.”

A controversial, anonymous article in the February 2, 1910 edition of La Crónica warned of the patriarchal monopoly of the Catholic confessional.

The confessional scares me, and I advise mothers to teach their daughters to confess their guilts and faults not to God, or to confess them before the lattice of the confessional, to the ear of a man who has no right to listen to the conscience of youth, and who is susceptible to feel all of the human passions precisely because he is human and celibate. The mother loves her daughters with heartfelt, immense, pure, and incomparable love, and she is the legitimate confessor of the family and the legitimate counselor of the home.

Then, a week later, a Crónica piece titled “Vulgariza La Revista Catolica” clarified the publication’s position: “We do not want the woman to stop believing in whatever God strikes her fancy. … We only want to destroy the idols of the woman’s heart and have her turn her face once again to her God, so that she can adore him with more intelligence, freely.”

By the time “Debejamos Trabajar” appeared in the December 7, 1911 La Crónica, Idar had secularized the sentiment, so that it appeared more palatable (if not more digestibly feminist): “Working women know their rights and proudly rise to face the struggle. The hour of their degradation has passed. … They are no longer men’s servants but their equals, their partners.” And she was known to take it even a step further, flatly proclaiming, “Educate a woman, and you educate a family.”

In a 2017 interview with the San Antonio Express-News, González, an associate professor in history at the University of Texas-San Antonio, said Idar “worked toward the creation of a better world where women and men of all backgrounds would be able to thrive and contribute to their communities. She labored for social justice, for an end to racism and segregation, for women’s rights, and for the rights of children to have an education and therefore greater opportunities.”

Idar and her family utilized La Crónica to support the creation of El Primer Congreso Mexicanista (the First Mexican Congress) to advocate for justice and equality for Hispanic people in Texas. The Congreso met for 11 days in September 1911. They recognized Mexican-American achievements, celebrated their Mexican heritage, sponsored empowering speeches, and staged festive community performances. Idar and other women were prominent participants in the event and subsequently formed the Liga Femenil Mexicanista (the League of Mexican Women, of which Idar was the first president).

In 1913, Idar crossed into Mexico and worked with La Cruza Blanca (a medical aid organization like the Red Cross) during the Battle of Nuevo Laredo in the Mexican Revolution.

La Crónica closed its doors after Nicasio’s death in 1914, and Idar became a staffer for another Spanish-language newspaper in Laredo, El Progreso. When El Progreso published an editorial by a Mexican revolutionary named Manuel Garcia Vigil that was critical of the United States’ occupation of Veracruz later that year, members of a local company of the Texas Rangers appeared outside the door of El Progreso with the intent to shut it down, but they hadn’t planned on encountering Jovita Idar. She defiantly berated them, reportedly issuing a succinct lecture on the First Amendment and freedom of the press. The Rangers retreated. They returned the following morning — when Idar wasn’t around — to destroy El Progreso’s offices and printing equipment and arrest the other employees.

*****

Idar’s stand against the Rangers was incredibly brave considering their reputation for violence and bloodshed during encounters with Mexican and Tejano populations along the border at the time, and the history of her fearlessness and resolve is thankfully becoming more widely known. But a largely forgotten incident early in her life had a more profound effect on her and her family’s social and political outlook (and perhaps the city of Laredo itself) because this incident shaped the family’s views moving forward. A brief account of the Laredo Smallpox Riot is available online via the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas.

LAREDO SMALLPOX RIOT. A smallpox epidemic at Laredo that began in early October 1898 led to events that eventually climaxed in March 1899, when a violent showdown between Mexican Americans and Texas Rangers resulted in the immediate death of one man, the wounding of thirteen, and the arrest of twenty-one participants. On October 4, 1898, Laredo physicians began noticing a disease resembling chicken pox among the city’s children. The first death directly attributed to smallpox, that of a Mexican child on October 29, prompted Mayor Louis J. Christen and local officials to start a committee to investigate reports of the illness. By the end of January 1899, more than 100 cases of smallpox had been reported in Laredo. Dr. Walter Fraser Blunt, State of Texas health officer warned that more systematic and thorough measures would have to be taken to control the epidemic. Dr. Blunt’s instructions included house-to-house vaccination and fumigation, the burning of all questionable clothing and personal effects that could not be fumigated, and the establishment of a field hospital to disinfect patients. This field hospital was in effect a quarantined area, referred to as the “pesthouse.” Most of the vaccination and fumigation efforts were directed at the poorer barrios of the city along Zacate Creek on the east side of town.

Conditions worsened to such an extent that on March 16, 1899, Blunt arrived from Austin to take charge of efforts to control the epidemic. A serious problem arose when a number of Laredo residents began to resist the vaccinations and fumigations. Blunt responded by requesting the services of the Texas Rangers to help medical teams carry out house-to-house vaccinations and fumigations. On Sunday, March 19, 1899, a small detachment of Rangers arrived from Austin and joined in the efforts to get all residents immunized. The arrival of the Rangers heightened the apprehension of some people being forced to submit to the radical health measures. Friction between Mexican Americans and Texas Rangers was long-standing in South Texas. Where the Rangers met resistance, they broke down doors, removed occupants by force, and took all who were suspected of having smallpox to the pesthouse. A throng of angry protesters gathered and showered the Rangers and health officials with both words and rocks. In the ensuing melee, Assistant Marshal Idar was hit on the side of the head by a stone, and one of the protesters, Pablo Aguilar, received a shotgun wound in the leg.

“Assistant Marshal Idar” was Jovita’s father, Nicasio.

As educated members of la gente decente, Jovita Idar and her family were caught between historically abusive and overbearing American law enforcement and medical officials and, on the other side, the uneducated, “pariah”-like members of their fellow Tejano and co-national community.

The next day, the Laredo Times reported that Deutz Brothers, a local hardware store, had “received a telephone order for 2,000 rounds of buckshot to be delivered to a certain house in the southeastern portion of the city, but instead of filling the order, the authorities were notified and given the location where the delivery was to be made.” Sheriff L.R. Ortiz quickly obtained a search warrant and took with him Capt. J.H. Rogers and his detachment of Texas Rangers. The elite squad had been reinforced that morning with the arrival of more Rangers on the train from Austin. Together they began a house-to-house search in the immediate area where the ammunition was supposed to have been delivered. At the home of Agapito Herrera, trouble began for Sheriff Ortiz and the Rangers. Herrera, a one-time Laredo policeman, met the lawmen outside his home and took Ortiz aside to talk privately. As the discussion heated up, a youngster standing in the doorway shouted “ya!” and darted inside. Almost simultaneously, while the nervous Rangers drew their guns, Herrera disappeared into the house and ran out the back door accompanied by several armed men. In the ensuing gunbattle, Capt. Rogers was wounded in the shoulder by a bullet fired from Herrera’s pistol. Herrera himself was shot in the chest by Ranger gunfire. Ranger A.Y. Old ran up to the wounded Herrera and pumped two fatal shots point blank into his head. The dead man’s sister, Refugia, was shot in the arm, and a friend, Santiago Grimaldo, was shot in the stomach.

After evacuating Rogers, Rangers returned to find an angry crowd of about 100, some of whom were armed, gathered around Herrera’s lifeless body. After the hurling of more taunts, someone in the crowd fired a shot. The Rangers promptly opened fire into the crowd, wounding eight, including one man mortally. As evening approached, the Rangers retreated to Market Square. All through the night, sporadic gunfire could be heard in the same troubled neighborhood. Realizing that the situation could easily worsen, the Rangers called on the cavalry unit stationed at Fort McIntosh for additional support in restoring order. On the morning of March 21, the Tenth United States Cavalry [composed of African-Americans], under the command of Capt. Charles G. Ayers, moved into the affected neighborhood to maintain the peace and assure that the work of controlling the smallpox epidemic continued unhampered. Rangers also patrolled the area, searching for and arresting anyone they thought involved in the riot. Liberal journalist Justo Cárdenas and twenty others were arrested. Few disturbances were noted in the days that followed. The army seemed to have taken control of the situation, and Mayor Christen pleaded with other areas of the state to send food and clothing to the victims of the epidemic. Throughout March, many children continued to die of smallpox, but in April, the number of deaths decreased dramatically. The situation had improved so much that by May 1, 1899, Blunt ordered the quarantine lifted.

Today, one in five Texans is still not vaccinated for COVID, and certainly during the pandemic’s heights and leveling off, our uneducated, ill-informed or ignorant, “pariah”-like neighbors (of all ethnicities) reacted in much the same way their counterparts did in Laredo in 1899. The difference is that the undereducated and underprivileged members of the Tejano and Mexican community in Laredo at the turn of the 19th century had a legitimate excuse. They faced Juan Crow discrimination and underfunded education systems.

The Texans who verged on rioting and violence regarding the COVID vaccinations at the dawn of 2020 had complete access to informational opportunities and educational programs, and their obliviousness to public health considerations and borderline spiteful intransigence are still inexplicable and stupefying.

Jovita Idar’s family bore Nicasio’s attackers no ill will, and the patriarch, two of his sons, and his daughter set out to help them by educating them and providing them an alternative, cogent voice in the Mexican-American population’s ongoing struggles for equality and justice in their community. And not for monetary reward, fame or political gain — but for the future of La Raza.

Idar married Bartolo Juarez in 1917 and moved to San Antonio. Though childless, she helped raise the children of her sister Elvira, who passed away during childbirth. Idar established the Democratic Club in San Antonio and became a precinct judge for the party. She also created a free kindergarten and served as an interpreter for Spanish-speaking patients at a local hospital. Idar struggled with tuberculosis for many years and succumbed to a pulmonary hemorrhage at the age of 60 on June 15, 1946.

Jovita Idar championed diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) a century before it was a thing, well before it was cool, and way before Anglo conservatives made a political football out of it. And they were no match for her almost unparallelled Third Estate bum rush. She was more Texan and American than the entire lot then — and now. And her quarter grants no quarter.

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is the author of Tell-Tale Texas: Investigations into Infamous History and The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas.