Clumps of lightly strewn litter pockmarked the apartment grounds as Ivan and Lorenzo approached. The two 18-year-olds recently kicked out of a local charter school were polite and soft-spoken as they recommended spots for lunch. We are concealing their last names to protect their privacy.

Lorenzo, a Black man, darted back to his apartment to grab his phone as Ivan, a Hispanic man in slippers and a fuzzy gray sweater, described a recent car accident that totaled his Dodge Charger. He showed me his bruised left arm, adding that buses, fortunately, have offered a way for him to find work at area fast-food restaurants to save money, reenroll in school, and apply for college. As we all chatted over fried chicken a few minutes later, both teens expressed their eagerness to earn their GEDs and attend Tarrant County College.

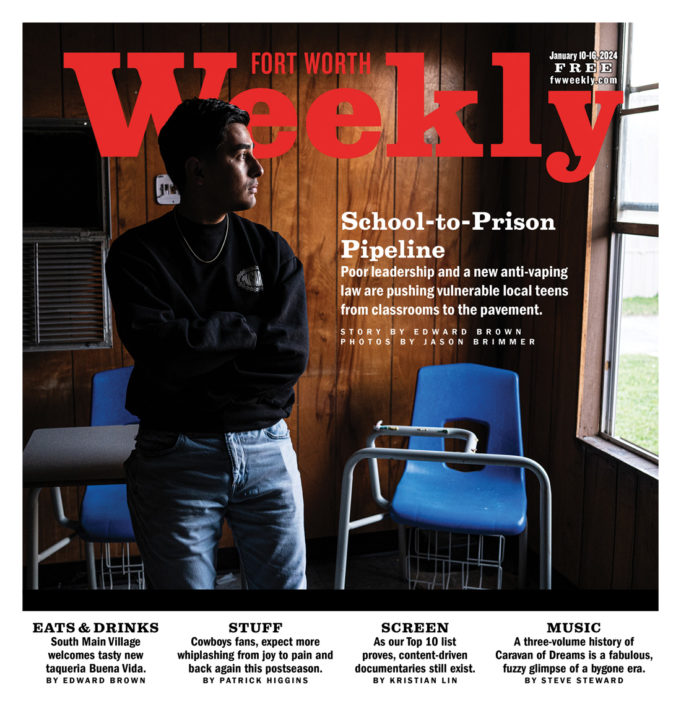

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

At the beginning of the fall semester, Lorenzo and Ivan were “withdrawn,” which essentially means expelled, from Fort Worth Can Academy-Westcreek on the South Side. The campus is one of 13 public charter high schools across Texas managed by Texans Can Academies, which launched in Dallas in 1985 and whose stated goal is to provide students with the “skills necessary to thrive beyond the classroom.”

Lorenzo, whose mother died last year, has been homeless for the past two years. “My pop was staying with my uncle, and I had a falling out with my uncle. I’ve been homeless since. When [my uncle] kicked me out, that’s when I dropped out of school.”

The missed classes at Fort Worth ISD’s Paschal High School meant Lorenzo had to enroll at Can Academy a year ago. In September when he was just months from graduating, he was caught vaping along with a handful of other students. School leaders immediately withdrew him. As a security officer escorted him out, Lorenzo alleges the principal said she was going to do whatever she could to prevent him from reenrolling anywhere.

Lorenzo feels he “should have been given a second chance — I never got in trouble before that.”

Ivan said his problems began at Fort Worth ISD’s Paschal High School when instruction became virtual during the pandemic. Under the lax format, he frequently skipped class, which resulted in suspensions and enrollment in Can Academy during his junior year. At the beginning of his senior year in September, Ivan said a misunderstanding led to his removal from the charter school.

“I got into an argument with the principal,” he said. “She thought my friends and I were about to fight. We were not going to fight. I spoke up about it.”

Both teens said they were never allowed to defend themselves and that no one from either the charter school or Fort Worth ISD contacted them with options for reenrollment. The teens said they are actively trying to reenroll at either Can or somewhere in Fort Worth ISD but that neither entity is returning their calls.

Daniel Garcia Rodriguez, a former Can Academy student and student advocate, left the charter school early into the fall semester, partly out of frustration over the forced removal of students like Ivan and Lorenzo over seemingly minor offenses. Garcia, based on first-hand experiences working at Can and also Polytechnic High School, said “withdrawn” is basically “expelled.”

These teens “have gone through so many things that right now, more than ever, they need an environment to empower their recovery,” Garcia said. “The decision to kick them out of school hidden under the umbrella of being withdrawn was one of the worst things that could happen to the kids.”

Based on the most recent data from the U.S. Department of Education, middle and high school students who are expelled or suspended are up to 10 times “more likely to drop out, experience academic failure and grade retention, hold negative school attitudes, and face incarceration than those who are not. Black students [composed] 15% of the overall U.S. school population but received 39% of out-of-school suspensions.” In 2020, the Texas Criminal Justice Network, a nonprofit working to end mass incarceration, found “no evidence that suspensions and expulsions are an effective method of changing students’ behavior in schools.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

Over the past decade, Black Fort Worth ISD students have made up only 20-25% of overall enrollment but accounted for nearly half of all suspensions, based on data from the U.S. Department of Education and released to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram via open records request. And Fort Worth ISD is not alone. The disparity rages nationwide. Multiple studies point to cultural discrepancies between students and school leaders as the root causes of the obvious disciplinary bias against Black children.

Although a Can staffer initially left a voice message with us after we contacted them, the charter school has not responded to our repeated calls to the main office. We will update this story if we hear back.

Ivan feels policies at Fort Worth ISD and Can Academy have made graduating unnecessarily difficult when economic barriers and other challenges are hard enough to overcome.

“Just because we mess up a few times shouldn’t mean that we do not get the education that we need to be successful in life,” Ivan said. “Getting in trouble one time shouldn’t get you kicked out.”

*****

Garcia’s own troubled past guided him toward a career in teaching in public schools, a space where he felt he could motivate and inspire students without resorting to punitive approaches to instruction. The 29-year-old Brownsville native is the first U.S. citizen in his immediate family. His namesake older sister, Daniela, died at birth in Mexico. For his parents, the American dream meant more than access to material comforts.

“The American dream was about access to education,” he said. “Being a U.S. citizen to undocumented parents in the States came with challenges.”

Garcia’s parents moved to Fort Myers, Florida, in the early 2000s for better work opportunities.

“I was a bouncy kid in search of affirmation,” Garcia said. “I slowly started to see that our schools weren’t friendly toward that type of behavior.”

Educators, he said, relied too heavily on fear-based models. By fourth grade, Garcia and his friends saw the full effects of the state public education system. Misbehaving fourth graders were ordered to fully extend their arms while holding heavy textbooks for several minutes at a time. Talking in class and fidgeting forced Garcia’s elementary teachers to remove him from track and field.

“That was where I felt community,” Garcia recalled. “That was my first time being excluded because of how my teacher perceived me. I began disassociating myself” from school.

By middle school, Garcia’s frustration with the overly punitive school system led to frequent stints of in-school suspension. More than a decade later, he sees his early punishments as the beginning of his potential school-to-prison pipeline that began with a felony (grand theft auto) during his freshman year of high school.

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

In-school suspension was “one large classroom,” he recalled. “Complete silence. There was never an opportunity to grow or have due process. It felt like an exclusionary practice because we had a population of white students at our school. A majority of suspended students were Black or Latino. I was there for talking too much or laughing. Dress code violations landed many students in in-school suspension. We were never given guidance or tools for how to moderate our behavior. Students were dealing with emotional triggers” from home life.

It is natural for any child or teen who is singled out and excluded to act out, he continued. At no point did teachers in Florida and later Fort Worth take time to ask about Garcia’s stressors. Returning to class after a week of in-school suspension was humiliating, and his teachers made no effort to catch him up on missed work. Looking tough became a protective mechanism.

The 2008 housing market crash caused a shortage of work in Florida, so Garcia’s family moved to Fort Worth around 2010. He enrolled in ninth grade at North Crowley High School. Initially, high school soccer offered an alternative to gang culture, but his coach booted him from the team due to lingering disciplinary problems. As crushing as that experience was, verbally humiliating words from an English teacher pushed him to drop out of school completely and begin committing petty crimes, including that felony.

“She said in front of my friends that I was not going to make it anywhere in life,” Garcia recalled. “That was a breaking point. I turned to the streets. I left my house and moved in with someone I was dating. I didn’t care about school anymore. I started smoking, selling drugs, and carrying weapons.”

Even with loving parents, severing his ties with school left Garcia feeling lost. It wasn’t long afterward that he stole the car and evaded arrest. He pleaded guilty to the felony charge that remains on his record. Possibly because it was his first offense, Garcia was given a relatively lenient sentence: one-year probation and community service. He enrolled in Can Academy-Westcreek to complete high school. The kindness of one person, Marine Corps mentor Sgt. Ray Franklin, saved the troubled teen. Franklin helped Garcia find a job and graduate from Can Academy.

Though Garcia was not allowed to become a Marine because of his criminal record, Franklin still helped him find work while motivating him to finish school.

Sgt. Franklin knew about Garcia’s record, but “he didn’t care,” Garcia said. “He spent so much time with me and reaffirmed my existence. He came to my house to check on me. That relationship completely changed the course of my life.”

Can Academy staffers, Garcia alleges, routinely engaged in bullying tactics during that time.

“I remember teachers yelling at us,” he recalled, “suspensions being given out like nothing. The assistant principal would wait at the parking lot. If you were late, he’d point at you and say, ‘Go home.’ He would pick fights with kids, pushing students to the point where they would act out.”

Following the pattern of his past teachers in Florida and Crowley, Can educators allegedly failed to inquire into or even acknowledge the stressors and life situations that cause students to be tardy or short-tempered.

“I had so much anxiety about being late,” Garcia said, adding that he once received a speeding ticket while racing to school after a late night of working and minimal sleep. “The students there didn’t want to be late. We aren’t doing this because we don’t care. There was shit we were going through making us late.”

In 2017, Garcia co-founded United Fort Worth while studying at Texas Wesleyan University. The grassroots group that advocates for social justice causes now manages a community center in the Polytechnic Heights community. Garcia headed the nonprofit for five years, but he said his childhood brushes with the school-to-prison pipeline called him to mentor troubled youths.

At the end of 2022 and after working for a few months at Polytechnic High, Garcia resigned, claiming school leaders were not receptive to the reform-minded teachers’ advocacy for listening to students and considering the challenges and traumas at home when meting out discipline. When Garcia tried to reenroll students, he alleges, school leaders were more concerned about enrollment numbers than the welfare of the withdrawn pupil.

“They were worried that if a student already dropped out, he would only drop out again,” Garcia said. “And that would make the school’s numbers look bad.”

His former principal at Can-Westcreek was still heading the Southside charter school, so Garcia applied and was accepted to work as a student advocate, one of two such positions, at the beginning of 2023. As the name entails, student advocates are counselors of sorts and use their personal knowledge of students to solve issues of truancy and misbehavior without resorting to expulsions or suspensions. Garcia was able to reach many of his goals during the spring semester under the leadership of Principal Ku-Masi Lewis.

“I wanted to be in a space to empower young people who have experienced things I experienced,” he said, “but when I was a substitute at Polytechnic High School and student advocate at Can Academy, what I saw was triggering. My inner child was screaming out. I saw adults yelling at kids. I saw a lot of suspensions. One student, a young Black girl, was tackled by a police officer and embarrassed. I saw a teacher tell a student that he doesn’t care about him. I saw the embarrassment in the kid’s face. The same thing happened to me.”

One Can Academy-Westcreek employee who asked to go by LaKay said her campus provided a safe space for students before the current principal and assistant principal took office in August. The campus is down to one counselor now, LaKay said, and the atmosphere feels more like a “juvenile detention center” than it did the year prior.

“If a student is late in the morning, then they have to wait until second period,” she said. “They are waiting out in the cold when they should just let them in. When I was a student at Can, I didn’t have the support of my parents. I can see how these students feel. I’ve heard the principal tell a student, ‘It’s OK if you just get withdrawn,’ knowing that Can might be the kid’s last option.”

During the spring 2023 semester, Can leadership “started giving me some leeway,” Garcia recalled. “It wasn’t perfect, but I started to see changes in my students. There is a benefit to learning [the students’] stories. Once you understand their story, you get a better idea why there are behavioral issues coming up.”

Garcia’s office became a safe space where students dealing with stressors from within and outside the school could converse with the student advocate. Over the summer, Lewis left the school, and Can-Westcreek hired two new principals. In the days before the start of the fall semester, which is divided into two quarters, the two new leaders communicated their zero-tolerance policies to staffers, Garcia said.

“In the first two weeks of the fall semester, 15 kids were withdrawn for vape-related issues,” Garcia said.

The timing was expected. September saw the implementation of HB 114, which allows schools to easily expel students for vaping and criminalizes student possession of five or more e-cigarettes as a potential Class B misdemeanor. In a press release, Fort Worth ISD officials said that any student found in possession of a vape pen would be disciplined in accordance with the new state law.

Around 2.5 million middle and high school students reported using electronic cigarettes last year, based on findings from the National Youth Tobacco Survey. The popularity of vaping among teens, the survey says, is partly due to marketing efforts by electronic cigarette companies and the placement of e-cig stores near youth-heavy areas, like high schools. Although no Fort Worth law restricts how close stores can open near schools, the businesses cannot advertise tobacco within 1,000 feet of a school. A cursory look at Google Maps found several vape retailers within a block or two of Can Academy-Westcreek.

Many North Texas schools have adopted zero-tolerance vaping policies following the passage of HB 114, adding yet another means of forcibly removing students without considering the individuals’ circumstances or emotional predispositions. After several months at Can Academy and just as the fall semester was starting, Garcia resigned.

“The school year has been filled with threats and isolation for me,” Garcia wrote in his letter to Can’s principal. “I felt like I no longer have access to create the space necessary to uplift my students through the student advocate role. I realized this when a frustrated student on my caseload was vocal and angry that they were not able to meet with their advocate after multiple requests. My students needed to talk to someone they shared trust with. I have also been hurt by the number of kids pushed out from our school by our attempt to address vape abuse. Our school is supposed to prevent dropping out, not accelerate it.”

The culture at Can-Westcreek has become decidedly more authoritarian and punitive since September, said Kyndal Tell, a senior set to graduate at the end of the year. Tell said she suffers from sometimes debilitating anxiety and depression. Her years in two different public schools were marked by bullying by teachers and fellow students. During the pandemic, online courses through Crowley High School gave her the chance to disconnect from her peers, which was welcome because being around too many people, like classmates, worsens her anxiety and depression symptoms. She soon dropped out entirely for two years. When she enrolled at Can Academy-Westcreek in early 2022, Tell was initially impressed with the program, especially how it allowed students to choose how many courses they could take each quarter. The new administration created a decidedly more hostile learning environment, compelling Tell to share her experience even at the risk of retaliation by school leaders.

Under the new administration, students are no longer allowed to contact student advocates and counselors directly.

“You would think the school is for criminals,” Tell said. “We are treated like prisoners. We aren’t allowed to have backpacks. Our advocates can’t be our advocates anymore. Mr. Garcia’s office was a safe space for us. Now, we can’t step foot in any of their offices. He understood what we were going through. After talking to him, it felt like we had someone on our side.”

Photo by Jason Brimmer.

A few weeks ago, Tell documented an intercom message from the principal ordering teachers to confiscate students’ smartphones. Tell said the principal threatened everyone with withdrawal if they complained.

“I was so baffled,” she recalled reacting at the time to the veiled threat. “They have students who really need this school’s help. They were telling us, ‘Hey, shut up. Do this. If you don’t like this, go ahead and withdraw.’ ”

Like many students at Texans Can Academies, Tell comes from a loving but sometimes struggling home. She lives with her grandparents and mother, who works remotely, meaning their one computer is often not available for school use. After graduating, Tell plans to take a short break — a “breather,” as she puts it — before pursuing a career as a vet tech.

“I hear a lot of kids say that if they get withdrawn, they don’t care anymore,” she said. “Some will just drop out and work. [School leaders] could be putting energy into addressing bullies. Instead, I hear more threats about kids being expelled over phones and vapes.”

The school’s problems, she said, aren’t tied to the teachers so much as the new administrators.

*****

“If you force out a young man from school, the only place that can offer some structure to them is the streets,” said Rodney McIntosh, founder of VIP Fort Worth.

As head of the nonprofit focused on ending cycles of gun violence in Fort Worth, McIntosh sees the crucial role public schools play in preventing teens from entering the school-to-prison pipeline.

Once on the streets, “they are the perfect candidate for group violence,” he continued. “I don’t like to use the word ‘gang’ because it’s changing. There’s nothing on the streets that will allow him to be productive — just death, murder, drugs, and gangs.”

One of the most important actions that teachers, mentors, and school leaders can take is to listen, McIntosh said.

“Because these students are so young, we tend to think we can project our thoughts onto their situations,” he continued, “but if we listen, we’ll know why they are hurting.”

Through his nonprofit work, McIntosh implements his experience, listening to the young men while urging them to talk and think through their choices.

I may say, “ ‘Little bro, are you telling me you are willing to find yourself incarcerated because of a statement someone made to you when he didn’t even put his hands on you? The thing that you are angry about is not as important as you think it is.’ ”

Teens and young adults are often not given the opportunity to express themselves, he added.

“They feel like no one listens,” he said.

McIntosh said public school leaders are regrettably reluctant to work with Black mentors with a history of gang membership or a criminal record, even though those men are exactly who at-risk youths would listen to and learn from.

“I believe in our school district and community,” he said, “but our members are often blocked from speaking at schools. They say it’s for safety reasons. Their [mentors] are the people who want to be invested. These young people would respect them. The [Fort Worth] school district needs to understand that the problem is bigger than them. The people with solutions are the closest to the problem.”

When asked about their future plans, both Ivan and Lorenzo expressed dreams of college, careers, and families.

“I want to be an entrepreneur or into real estate,” Ivan said. “I feel like I’d be good at it because I’m a people person. I’m good at talking to people.”

The 18-year-old said he’ll pursue a bachelor’s degree in sales, something he described as practical, once he is able to finish high school or earn his GED.

After years of suffering from homelessness and financially insecurity, Lorenzo said his first priorities are financial stability and a steady home.

“I want to own my own business,” he said, adding that owning a washateria and trading stocks are two of his goals. “I want to be able to help people be able to wash their clothes. There aren’t always Laundromats in low-income communities.”

Ivan wants to own a home within 10 years, own a company, and start a family.

A Fort Worth ISD spokesperson said there are several ways for high school students who are currently unenrolled to complete their secondary education. The options include enrolling in the district’s credit recovery lab or online courses.

“They can also enroll in our Success High School program,” the spokesperson said. “This is a program designed for students who may be returning after having dropped out. The program offers classes on nontraditional schedules to offer students flexibility. The best first step a student can take to start on the path of enrollment is to visit their neighborhood school.”

The spokesperson added that students and families may also contact Enrollment@fwisd.org for help navigating the enrollment process.

In its 2020 report, the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition cites restorative justice as an effective alternative to punitive practices like expulsions and suspensions.

“Using methods such as group conferencing, healing circles, check-ins, and mediated victim-offender dialogue (VOD), restorative justice helps the actor consider the consequences of their actions,” the report finds. “From the requirement of taking responsibility for the wrongdoing to making a sincere apology, [to] developing a plan for restitution satisfactory to the victim, [and] to ultimately following through on that plan, professionals and students agree: Far more accountability is required of a student making amends through a restorative justice model than one who is sent home via suspension or expulsion.”

McIntosh, through his nonprofit, encourages group discussions among community elders and at-risk youths. Any topic is on the table, he said, from advice on how to raise children — many of the boys and young men were not raised by their fathers — to chats about mental illness and the risks of using drugs.

In society and school, many of these young men “lack the opportunity to express themselves,” McIntosh said. “They have more ideas than we think. We have to be able to listen.”

Thank you ever so for you article post.Much thanks again. Great.

Got about halfway through this article and couldn’t stand the whining anymore. Here’s a suggestion for today’s miscreants and snowflakes, follow the rules. Most everything complained about in this article is against the school rules and the laws of the State of Texas Choices have consequences, you made a bad choice now live with it.