Caravan of Dreams wasn’t exactly before my time, because I moved here from California to go to TCU in August 1996, which would have been near the end of the legendary three-story venue’s 18-year run. But at the time, I was a recently minted 18-year-old ignorant of just about everything that wasn’t Star Wars trivia, a Bible story, or a ska punk band. I had near-zero interest in jazz, and when I heard about famous jazz performances at Caravan, it did not move my meter in the way that an OC Supertones concert at a church in Bedford would have.

Years later, I’ve learned what I had missed, gleaning second-hand nostalgia from comments in the Fort Worth Memories Facebook group — hundreds of iterations of “I saw ______ there,” the blanks filled in with everyone from Ornette Coleman and Eartha Kitt to the Jesus and Mary Chain and Ratt. Adding to the Facebook group’s collected memories last October, music historian William Williams made available his three-volume history of Caravan of Dreams. Caravan from Dreamland is a story that’s amazing, fascinating, and funny but, ultimately, a little heartbreaking because nothing in this city has ever followed in Caravan’s wake that comes close to what that place was doing.

I don’t really want to spoil any details because Williams serves them up by the truckload and every one is a reminder of how different things are now than they were between 1983 and 2001, when Caravan was open. Whether you saw shows there or have only heard a grandparent talk about this place, Williams’ history is a fun read, as his interviewees all seem to harbor a fond amazement at what they were participating in.

Reductively, Caravan of Dreams was the brainchild of some smart people living in a commune near Santa Fe, New Mexico, in the late 1970s. At Synergia Ranch and its Theater of All Possibilities, this group of “actors, artists, and scientifically minded environmentalists” wanted to bring the avant-garde to the mainstream. One member was local billionaire Ed Bass, which is how such a place ended up in downtown Fort Worth as opposed to a city with greater cultural cache.

What I learned about Caravan: You can’t tell its story without first talking about Bass, which Williams points out up front in the introduction. After describing the counter-culture community that Bass had joined in 1973, the Caravan Story, Williams wrote, “is also the untold story of the personal pilgrimage of Ed Bass himself, who traveled extensively with this radical theater troupe, funding and participating in many of their projects around the world, only to come full circle, returning home to bring this performing arts center into being and, in the process, transforming the desolate downtown landscape of the early ’80s into a vibrant cultural oasis.”

Caravan of Dreams’ opening show was on September 29, 1983, which had been officially declared Ornette Coleman Day by then-mayor Bob Bolen and featured Coleman and his band, Prime Time, whose kaleidoscopic free jazz was about as avant-garde as you could get. A live recording of the performance, Opening the Caravan of Dreams was the first release on the venue’s own record label, which would later produce 13 other albums by outré artists like James Blood Ulmer, Twins Seven Seven, and William S. Burroughs.

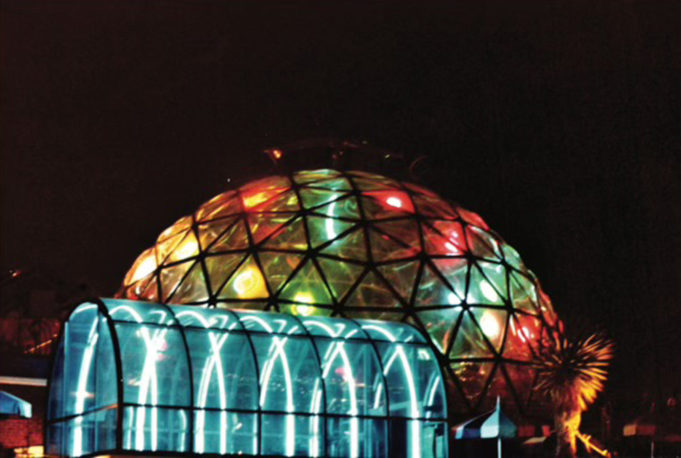

The venue’s three floors held a nightclub, a theater, and rooftop garden beneath a geodesic dome, and Williams has organized his three-volume history accordingly. The performances throughout the venue’s existence are what brought people in the door, but the space itself is just as memorable, and by breaking the text into these sections, Williams is able to give a lot of people their due — I never knew I’d be interested in a food-and-beverage director’s account of working at a world-class music venue, but now I know who Richard Bartman is. The interview with Caravan’s food-and-beverage director for a few years in the late ’80s is one of my favorites in the whole collection precisely because it made me imagine what it was like to be there, at a place that actively sought to expose average Fort Worthians to high culture, be it music, theater, visual art, or film, by a regular guy who got to sit at the soundboard while Winton Marsalis was playing.

What seems to have made Caravan particularly special was that for all the high-caliber entertainment provided to a pretty large room, performances were notably intimate, the stage being the same height as a dining table and right up close to the audience. This is not to say you can’t be close to a nationally touring act playing Tulips FTW these days, but in 2024, it just doesn’t seem like it’s the same thing as a show at Caravan of Dreams was. A lot has changed since then — the venue closed before social media and smartphones even existed — and concerts seldom seem to have the same kind of luster. But this is not to say that they cannot. Vis a vis the current state of affairs in Fort Worth music, reading about Caravan of Dreams’ magnificence and artistic aspirations gives me hope that someone — probably another billionaire, but whatever — might take a crack at intentionally bringing avant-garde culture to Fort Worth residents in such a way that the city starts to truly value it again, if for no other reason than that clueless 18-year-olds of tomorrow might become interested in a wider world.

Photo by Kathelin Grey

Working there were some of the best days of my life and I was behind the main bar for the final show! I even made it on the news. We were all devastated by the closing!