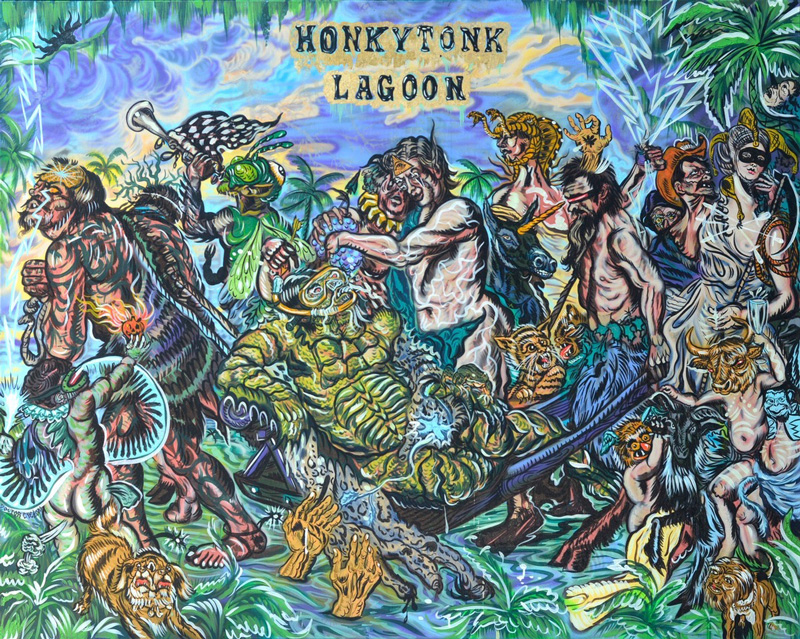

I don’t know how else to put this: Making sense of Clay Stinnett’s paintings in his solo show Honky Tonk Lagoon at Fort Works Art is like trying to learn the trajectories and backstories of every piece of flotsam rattling around the floorboards of your car while you’re floating in the midst of rolling it five times on the freeway, simultaneously processing that the cause of these chaotic vehicular acrobatics was an Instagram post you glanced at that had an old Taco Bell sign in the background. Also, “Islands in the Stream” is playing on the radio, and the box of loose action figures in the backseat has barfed them all into the moment’s defiance of gravity, and as Teela and the Baroness rattle off the dome light and the steering wheel, your last thought is about how Mattel and Hasbro must have been staffed by a lot of horny dudes.

If that doesn’t sound disorienting, then I can only say that you have to see his paintings for yourself to have your brain adequately scrambled in such a way. Last Saturday, Fort Works Art opened Stinnett’s first major Fort Worth show, and part of the joy for me, a longtime fan of his, was seeing the reactions of people who’d never seen his work before. Whatever face one might make while looking at a Where’s Waldo? book on acid, that was the general expression, like what your face would do if you were plotting a route on a super-funny, indecipherable map printed on the back of a Denny’s placemat.

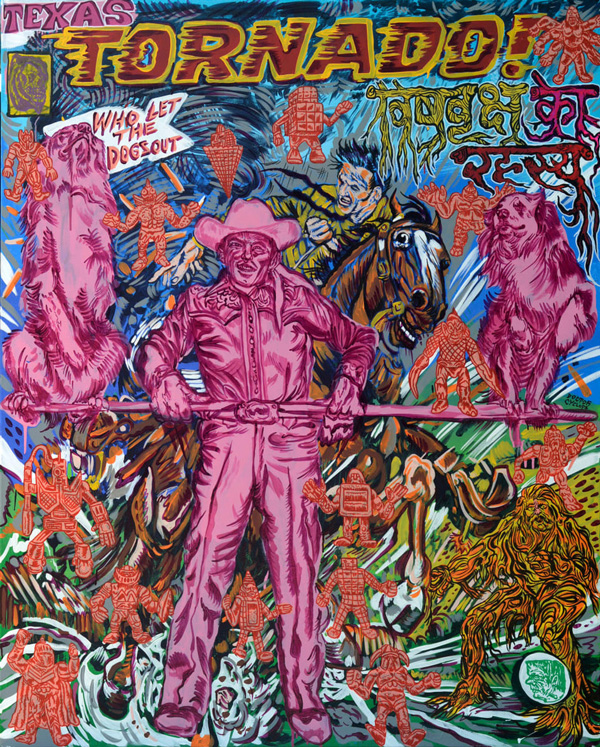

Clay Stinnett’s paintings are lowbrow and funny but so densely packed and chaotic that their trashy cornpone aesthetic ends up being a Trojan horse for what is actually fine art. Even when they’re monochromatic, there’s a narrative, or at least the impression that there is a narrative, like seeing the middle part of someone else’s dream in the middle part of your own dream, one where the ending is just out of reach behind the sign-off test pattern of a UHF station in purgatory. Put another way: They’re like a Hee-Haw episode imagined by Hieronymus Bosch, or one of Dallas by Breughel, maybe “Judith Beheading Holofernes” drawn by Mike Ploog or Jack Davis, rendered in thick black lines like a comic book chiseled into volcanic rock. Many of them are nearly impossible to view all at once, because if you step back, details you missed up close practically wag their claws at you.

Stinnett’s weird windows into hypothetical subconsciousness depict Dolly Parton’s incarnations folded upon themselves in kaleidoscopic refraction, snakes and werewolves fighting to exist in a world of motorcycle villains and fast food, and mind-bending portraits of country music luminaries and other faces that might look at home on the side of a carnival rollercoaster — whatever trip “Psychodelik Señorita” is on, her airbrushed eyes will burn an imprint on your psyche. From afar, Stinnett’s pieces look like visual distortion and clutter until you fall inside each one’s self-contained universe.

“I just tell myself stories,” he told me over the phone a few days before the opening. “I try to surprise myself, to entertain myself. Usually, humor is a big component. If it’s not funny, it’s at least dense and interesting. … I love layers. In this show, there are a lot of paintings that look like an abstraction when you step away. Like white noise. When you get up on it, you have to dig with your eyes. It’s not immediate gratification. I like creating art that you have to spend a little time with.”

Time — as it relates to his larger pieces like “Where’s the Beef?” — is sort of frozen within their borders. Stinnett’s subjects tend to be ’80s cartoon characters, or classic country singers, or TV actors who might have been on Battle of the Network Stars. In “Where’s the Beef?,” the old lady from the famous Wendy’s commercial is at the center of a vibrant, noisy hell, as giant frogs and motorcycles careen around her, an afterlife seemingly propped up on the unreliable backs of G.G. Allin and a pair of He-Man’s Battlecats. The garish pop-culture signifiers have their own velocities, as if blasting out of multiple realities all at once.

Stinnett shaped his artistic lens growing up in what he calls a “religious environment,” one where “TV was not allowed.” And when you think about the stuff he’s painting, it’s crazy to imagine someone with no formative media experience — i.e., when Magnum P.I. and Transformers were new — conveying this kind of subject matter.

“Besides college — mostly about conceptual stuff — I was self-taught,” he said. “I drew because I didn’t have anything to do. I was into comics and sports, baseball cards, stuff like monsters, horror, Halloween, religious violence. I would just copy stuff, study magazines, whatever I could get my hands on. I was into figurative stuff, portrait, face, how bodies interact with space and environment.”

When he was 19, Stinnett landed a job at Six Flags drawing caricatures. “It was like drawing boot camp just because of the demand. I knew what Dali was, but drawing caricatures blew the doors open on what was possible with stretching forms and adding in humor and distortion.”

Following his stint at Six Flags, he went to UNT, majoring in art and minoring in radio, television, and film, binging on all the culture he missed growing up. But like a lot of art students, the drag of assignments sucked the fun out of his practice. “I graduated from college in 2005 and was totally burned out and stopped painting.”

But around 2009, he started drawing flyers for local bands. At the time, he was working at a now-defunct bar on Lower Greenville in Dallas called The Cavern. “The owner was like, ‘You can draw — wanna do an art show?’ I got on Facebook and slowly started getting attention from my art, and then Texas Theatre asked me to do some paintings.”

These large-scale renditions of classic movie posters — what I would describe as having the guileless appeal of one of Henri Rousseau’s junglescapes but for, like, A Touch of Evil — reinvigorated Stinnett’s interest in the medium, and he started doing one-offs and commissions. He also became fascinated with collages, which, when you see the non-sequitur psyche-scapes in his work, seems self-evident. To him, processing the glut of images humans constantly ingest is a lot like a collage. With Honky Tonk Lagoon, he said, “I wanted to show conceptually, like, how we use social media. You scroll for 15 to 30 seconds. You get a whole handful of subjects in your face. I wanted to make art that was super-fast, banged together, rendered technically well.”

Stinnett is indeed prolific, and for this show, he submitted more than 80 paintings, no small feat for someone who makes his living churning out commissions and his own ideas to sell at just about any opportunity that pops up. That he was able to produce Honky Tonk’s body of work is solely because he had saved enough money from commissions and art markets to dedicate all his time to the show. “I just ate, slept, and painted.”

Typically, he will sell his art at pop-ups and other small-scale vending situations, as well as through his Instagram account @doctor_cyclops. For the Fort Works Art show, however, he upped his ambition.

“None of this stuff would be at a flea market,” he said with a laugh. “It’ll stay in the gallery system. I wanted to make the pieces all tight, dense, super-detailed.”

He has certainly succeeded, and if the crowd browsing his exhibition is any indication, his show is already a big hit. “At this point in my life … the idea of a grind or a hustle, that’s all I’ve been doing, taking almost every opportunity I could, doing as many commissions as I can. I’m just a worker. It’s fun, but for once, I got the opportunity to make art for the intended purpose of making art, trying ideas I wanted to play with. What’s funny — I was conservative with this show because of the market — I wouldn’t go too far out like I would at a metal club, y’know?”

Until such a club appears in Fort Worth, we’ll have to be content with the weird, wild grotesqueries currently hanging at Fort Works Art.

Clay Stinnett: Honky Tonk Lagoon

Thru Jan 13 at Fort Works Art, 2100 Montgomery St, FW. Free. 817-759-9475.

Courtesy Fort Works Art

Courtesy Fort Works Art

Courtesy Fort Works Art

Sounds like my kinda fracas.