It has taken more than five years, but Zach Edwards and his post-industrial project All Clean have finally released their debut album. Newfound fatherhood, lineup changes, a lengthy recording process, frustrating label hunting, and a global pandemic thrown in for good measure may have delayed the original timeline, but eager listeners’ patience will be greatly rewarded by Down from the Inner Work, a seven-song collection of ear-bleeding, groove-laden nightmare soundtracks.

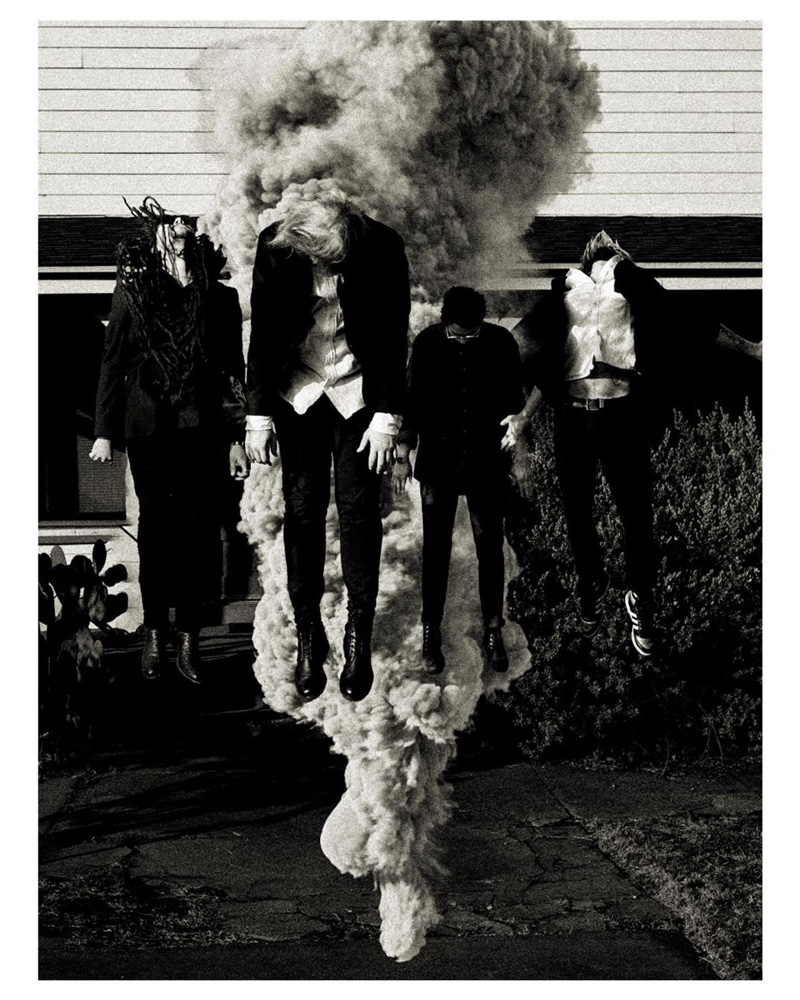

Photo by Colton Batts

“It’s been a long time,” said Edwards, who’s perhaps best known as guitarist for Son of Stan, Oil Boom, and Ice Eater. “It originally started off as a kind of recording project I was working on my own at home in, like, 2016.”

The album’s completion accomplishes a goal of Edwards’ that dates back a bit. “It’s been something I’ve always wanted to do ever since I was a teenager. Writing songs, playing all the parts, just wanting to do the solo multi-instrumentalist thing — it’s always been an aspiration.”

Though the recording process transitioned from his home to Dallas’ Elmwood Studios with the help of producer/engineer Alex Bhore (BULLS, Sarah Jaffe, This Will Destroy You) over the course of the last couple of years, Edwards did manage to record all the instrumentation himself — angular guitars, buzzsaw synths, thundering percussion, and howling vocals.

“Recording in a studio is my favorite thing in music,” he said. “It’s just the most fun. Being in a band by yourself can be difficult and lonely, but at the same time, when it comes to recording, I get to do whatever I want.”

Beginning with opener “A Time To Call My Own” through closer “See What I’ve Done,” with explosive percussion, unsettling electronics, and cat-yowl guitars, Edwards leads the listener through a torrent of chest-thumping, ear-piercing confessionals about dissolution, mental health, and dark and twisted fantasies that are as cathartic and therapeutic for the listener as they must have been for Edwards as he wrote them. Perhaps no line encapsulates Inner Work more than when on “A Time To Call My Own” he repeats almost soothingly to himself amid a barrage of brittle guitars, “It’s OK, it’s OK, it’s OK, it’s OK that you feel this way.”

As Edwards’ recording project progressed, and with some encouragement from Jacob Pulig, bassist for dance-rock outfit Vodeo, Edwards felt it might be time to put a band together to take his music to the stage.

“It was a pretty casual thing really,” he said of that decision. “It wasn’t as if I had an epiphany or anything. At some point after I’d written a handful of songs, I thought, ‘This is pretty good. Let’s get some guys together, learn these songs, and see what happens.’ ”

That original lineup featured Pulig on bass, Cole Austin (Panic Volcanic) on drums, and Brian Garcia (Son of Stan, Court Hoang) running the backing tracks necessary to realize All Clean’s signature industrial buzz onstage.

“It was plagued with technological problems,” Edwards said of those early shows. “There’s so many synths in my songs, and without having at least two dedicated synth players, we had to use backing tracks. I was learning to use Ableton Live at the same time we were starting out and [did not know] what the fuck I was doing, but we got through it.”

Pulig left after a couple of shows and was replaced by Miguel Santana (Supersonic Lips, Urn), and Bryce Braden replaced Garcia on the loops. Now All Clean’s current lineup, with Austin and Santana still making up the rhythm section, has abandoned backing tracks in favor of live synths and extra guitar provided by the addition of Aaron Mireles (Sub Sahara). Edwards feels it’s the perfect collection of musicians to bring his unique and haunting sound to life.

“I don’t know what it is,” he admits. “It’s just my songs. It’s my influences, I guess.”

When asked to name a few, Edwards seems to sum up All Clean’s angular industrial cacophony in just a few brushstrokes. Deftones, pAper chAse, Nine Inch Nails, and the little-known Chicago prog band 90 Day Men are a few that Edwards lists, and it’s easy to see each like the ribboned layers of folded Japanese steel combining to make All Clean’s edge.

Much of the delay in Inner Work’s release was due to Edwards label hunting, an effort that frustratingly died just short of the finish line. A deal was almost struck with an imprint that Edwards prefers to keep confidential, but after it fell through, he was forced to rethink and, more importantly, reinvest in how to raise awareness of the album.

“I didn’t really have a plan,” he said, “I didn’t think I was going to put it out on vinyl because that’s expensive. That’s what I was really hoping for with a label, just somebody to put it out on vinyl because that’s hard, and to help with promotion because I suck at it,” he laughed.

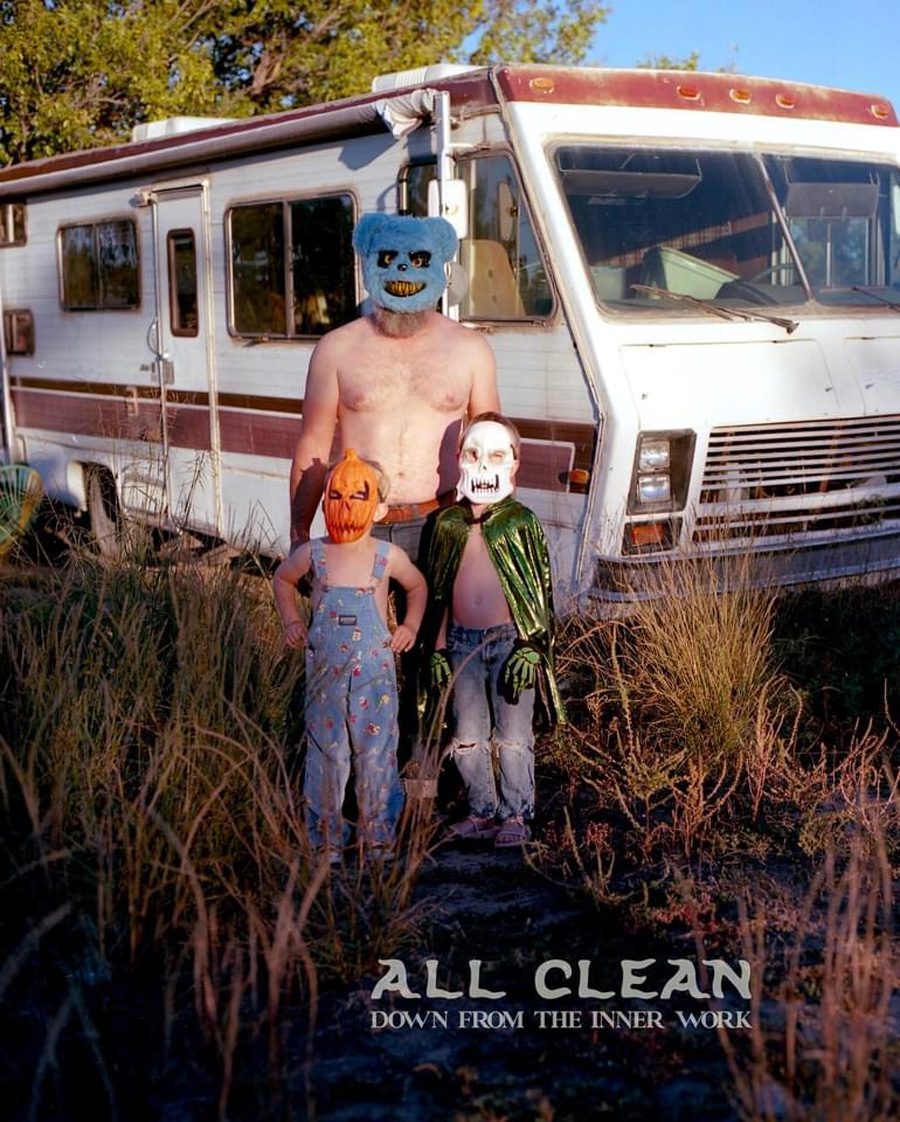

A social media surge, aided by the spooky photography of Colten Batts, helped bring an energetic crowd to Dallas’ Double Wide on Saturday to celebrate Inner Work’s release. It’s the sort of balance Edwards feels he’s made now that his priorities have shifted somewhat with music. He’s put less pressure on himself, and that’s made the experience more rewarding.

“On the one hand, I believe in this music,” he said. “I think it’s really good. I think people will like it, but I have no more aspirations of ‘making it’ in music like I did when I was younger. I just want to play my songs. Putting a record out certainly helps. I just want to do it on my terms and have fun and not stress about it. Keep it casual, a casual musician.”