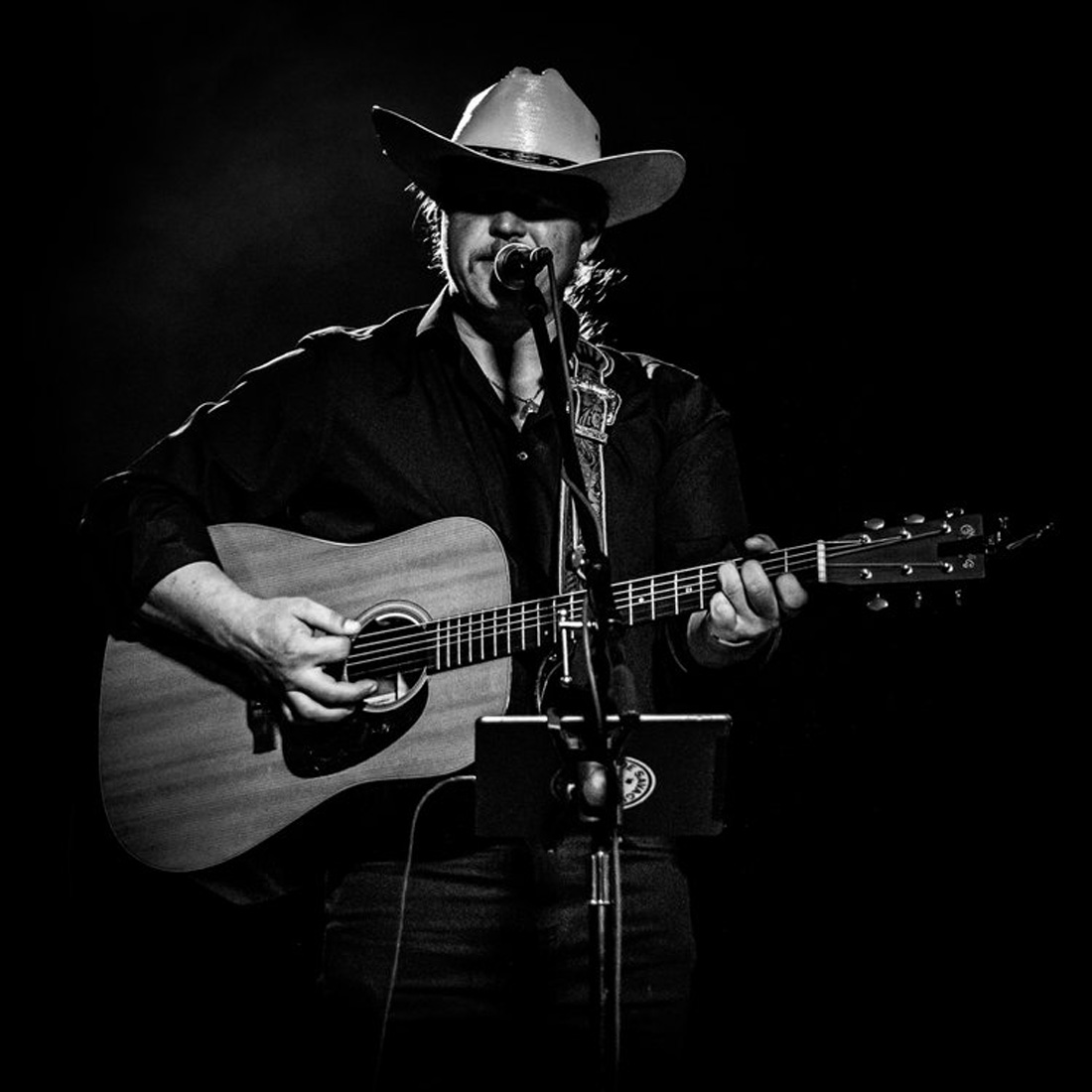

When country singer-songwriter Joe Savage first hit the scene in the middle of the last decade, he made the usual go of things. Solo shows at first, then putting a band together and recording and releasing records on a budget. Though he had some successes, that process never really gained him the kind of traction he was looking for. He felt the lack of “quality” content was a barrier between potential fans and their ability to find him. Two years ago, he shifted gears to elevate his fortunes with a renewed focus: simply great-sounding records.

“What I’ve found over the years is that by having lower production, less expensive albums out, when I did get fans, or a little hype at a show, when they would go listen to my music, the quality just wasn’t there,” Savage said. “I’ve spent the last couple of years trying to reverse that so that now when people go to look me up, they’re surprised at the production value of the content that’s out there.”

His latest effort in this regard is The Disappearing Blues, an album available exclusively through Bandcamp. Recorded with Taylor Tatsch at his recently relocated AudioStyles studio in Fredericksburg, it’s the third successive record Savage has tracked with the producer of Cut Throat Finches, Phantomelo, Shadows of Jets, and others, and the working relationship has provided exactly the production value he’s been looking for to add the legitimacy he felt he formerly lacked.

The working pair have set into a comfortable routine when it comes to making records. Savage will come down and track acoustic guitar to a click track with a scratch vocal. Tatsch will then add all the other instrumentation except drums — Austin’s Chris Mead (Peterson Brothers Band) provides the beats on this one. Once the instrumental arrangements are finalized, Savage returns to cut the main vocal.

Tatsch, Savage said, is “a great guy and really great at what he does. We’ve developed a great relationship. That’s why I’ve been giving him all my money for years,” he added with a laugh.

Tatsch is given co-writing credits on the album for his efforts. In addition, fellow Fort Worth singer-songwriter John Stevens is credited with a handful of tracks that he, Tatsch, and Savage fleshed out at a songwriter’s circle. Lyrically, Savage tackles themes of spirituality, fallen men, his relationship with his father, and redemption, while musically the album bridges Americana and gospel folk. It’s an aesthetic that sees Savage drift further from his classic country reputation, one often attributed to him that he never really felt comfortable having.

“It didn’t work,” he said flatly of being labeled a classic country revivalist. “That pressure builds — being pushed to dress a certain way or go for some outlaw country image, but it didn’t work for me. I definitely feel the pressure, and I want that kind of success [that seems to come along with it], and at times I’ve been willing to compromise thoroughly to achieve it, but now it feels nice to have just, like, a regular-guy look again.”

In addition to focusing more on good-sounding recordings, he’s changed the means in which he pays for them. Two years ago, he quit his day job, focusing exclusively on playing music, mostly at restaurants, bistros, and residencies. While not exactly taking his own music to legions across the nation, it helps him continue to hone his skillset as well as pay his bills.

“I just try to treat it like a job,” he said. “I could still be teaching. I used to teach grade school. I did that for six years. I used to work at Taco Casa, Burger King, and then be trying to write songs at night. Those all sucked and never made any money. It also takes all my energy away from the creative process, which my job right now still informs my creative process. It still makes me better.”

Though the six or seven three-hour sets a week can be a grind, he’s found it rewarding in ways other than just financial.

“I’ve just gotten so much better at everything,” he said. “I get better at singing still. My ear gets better. I’m a better businessman. I’m a better human being. The music works on you, too — the songs you chose to sing. Just like they can be healing to others, they can be self-healing.”

As well as helping pay for quality records like Disappearing, he was actually recently able to completely pay off his mortgage.

“I just paid off my land,” he beamed. “I’m not exactly living without any expenses, but I’m pretty damn close. To think that I was able to do that with music, that just makes it mean so much more to me.”

It’s one way in which his definition of success has perhaps shifted. Though he’s not hitting local venue stages as hard of late, he feels his methods are more methodical and calculated and will eventually provide more of a return on his energies and investments.

“I really do feel like I’m successful,” he said. “Am I successful in the way some guys like Charley Crockett or Vincent Neil Emerson are? Well, obviously no, but I honestly don’t know if I’d be happy [doing that]. Being responsible for grown men out on the road, making sure they eat and get home safe to their families with enough money to make it worth it? It’s a lot of sacrifice and responsibility that I haven’t had to take on, and I’m happier for it. Do I want to be doing the party shows, selling beer? Or am I fine just releasing music that I’m proud of and slowly building my fanbase with just me and my guitar, singing my songs and telling my stories?”