The first time I was fired from a rural newspaper for reporting inconvenient facts — read: facts not in line with the newspaper’s monetary gains — was back in 2012 during the heyday of the opioid crisis. Of course, back then, we knew it only as the nameless epidemic slowly killing our grandparents who could afford premium health care.

At the Waxahachie Daily Light, I was hired fresh out of college on a writing sample I sent the editor, complete with a persuasive call to seal the deal. Right away, Editor-in-Chief Neil White loved my plucky enthusiasm — as far as he could exploit it, as I realized later. Isn’t it ironic how often enthusiasm in young women is seen as a weakness to men in power whereas in other men it’s simply a good old-fashioned whiff of ambition.

White was well-loved because he specialized in articles about the greatness of the Chevys at our local dealership. Soon after I was brought on, the newspaper was bought by a conglomerate that had been going around buying up struggling news outfits to monetize the struggle presaged by the explosion of technology, bending the little guys to the big boy’s vast and impenetrable will. Or, ya know, capitalism. This eventually became the death of the Light and most other rural news outlets in deference to — let’s call it — greed news, a.k.a. “convenient facts.”

Stories that build morale in the community — that was the direction we were handed down from on high by way of jacked-up Chevys. It got so bad that at one point I was assigned stories like: Go ask people buying lottery tickets what they’re gonna do with all that loot!

It became clear that to be taken seriously or write anything substantive as a twentysomething at this rag, I had to pitch my own stories.

One story I found was about the director of the local massage therapy institute. Ginger Mensik was helping elderly folks trying to kick their opioid addictions through cheap massages and exercise regimens. The massages came at a huge discount as they were practice for the students about to graduate.

I loved everything about this story and what this lady was doing. Soon after I turned it in, White called me to say I was fired because it was illegal to write anything that sounds like medical advice, because the paper could “get sued.” Actually, he asked me to call him back right away and change the story as “quick as I can.” I put off calling him until the next day and never considered editing my story. Frankly, though, I had been slacking off in general due to the malaise that came with the beginning stages of confronting the truth about what was happening to the rural newspaper biz. Good thing I’ve always kept my day job. (Teaching pay is shit, too.)

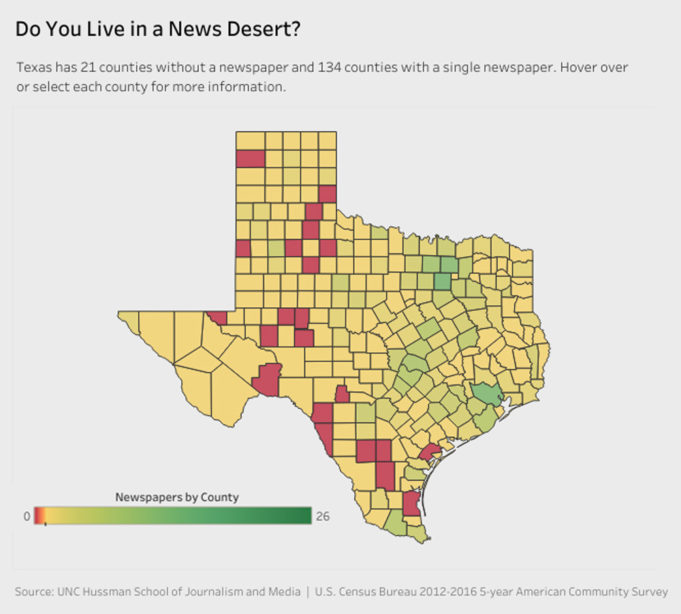

Public data from the last two decades show both revenue and newsroom employment have fallen over 60% across the country. Texas is among the top three states in the nation to experience the blight of “news deserts,” with the closure of nearly half of all media outlets — 211 out of 423 — since the digital takeover began around 2005. Since independent papers in small towns have been hemorrhaging money over the last decade, newspaper chains funded by corporate interests (actually, political lobbyists) now own more than two-thirds of the nation’s daily newspapers, many of which have slashed jobs and sold off the remaining properties. Every week, two more newspapers close — as news deserts grow.

In poorer, less-wired parts of the United States, it’s especially harder to find credible news about your community. Local news about businesses, events, and high school sports are some of the sections that mainly old folks in small communities seek out and discuss over a coffee at Dairy Queen. (I’ve actually seen this adorable display in several towns.) This plague on reputable information — information that has further been replaced by Fox “News”/MSNBC for adults and apps like TikTok for youths — has further exacerbated the decline in our sense of community throughout this digital age of sub-culture tribalism.

*****

Dispiritedly, I proclaimed the blatant fact that somehow Chief Pickup was unfamiliar with the First Amendment and my recording of the interview with Mensik, replete with testimony from the recovered elderly. His response was that I had majored in education (a more reliable career path to care for my daughter), not journalism, and didn’t know the first thing about writing. Mensik had also coincidentally called me later that day full of apprehension at losing her license. She informed me that the doctors had “this town on lock” and if I wanted to make some sort of happy horseshit difference, I should see my way “to Austin.”

I wish. Rural Texas towns feel inescapable to the impoverished as they are much more affordable than urban areas, and we are beset on all sides. I soon found myself in grad school at Texas A&M in the tiny town of Commerce due to said affordability. This is how I wound up getting shit-canned a second time from a rural newspaper, this time in the neighboring town of Paris, for trying once again to unabashedly print unmarketable facts (read: the truth) in small-town Texas. That’s about the time I gave up denying that this whole unshakeable-sovereignty-of-digital-media thing was here to stay and accepted its impact on my beloved written word. Further unpalatable for my broke ass was the impending doom that rural publications would go on bearing the brunt of.

I am nothing if not optimistic to a fault. Righteous indignation and raging hope are the only things staving off the sweet release of apathy, which is all that’s keeping real journalism alive. So, with that in mind, I chirped into my first autumnal day at The Paris News with what I hoped was an infectious air of optimism. The first hour was disheartening to say the least — I recall Editor Klark Byrd becoming noticeably surlier than his phone self while showing me to the bullpen. He interrupted my manic spiel on the merits of “new journalism” and the ways in which my revolutionary ideas would surely liberate these cornpone country folk and take the town by storm.

“Look,” I recall him saying, cutting my shit abruptly, “nobody under 50 really reads newspapers anymore. The only reason we’re still in business out here is to report on local sports and taxes, so just watch your ass and please don’t bring any shit on my head.”

The storm I was referring to quickly became a shitstorm — on this man’s head.

But this was only due to the fact that I proudly possess a predilection toward facts, and once again I found myself in a territory where the brutal truth meant bankruptcy for yet another publication read primarily by rural subscribers/voters, who most certainly did not prefer the sun in their eyes to their heads in the sand. In these rural areas, as “rural” is defined by a population of 50,000 or fewer, the subscribers/voters yearning for a time gone by were as much to blame for the papers’ deaths as the publishers pandering to these simple folk who had clearly moved out here not only to save money but also to avoid people and the realities of modern society at large.

According to the writers there, Publisher Clay Carsner was “quite friendly” with the local politicians, and, as a still cheerful young gal, I was once again hired to be the “goodwill ambassador” — of bullshit. Regale the elders with tales of their kids in public office and grandkids not in public schools. Once again, it was made clear to me that my job was to spin a bright and shiny yarn on stories from around the community. In all honesty, as a sentimental soul myself, I did this happily and well. Writing about beloved teachers’ surprise retirement parties, local charity donations to the needy, and adorable kiddos winning art contests? Yes, please. Where they went wrong was giving me my own column.

*****

The perk of this weekly opinion writing made the laughable salary tolerable as I finally got to pop off for a living. Admittedly, every reporter had a column considering that it took up space where the truth should have been. Contrary to my new-gal principles, the veteran writers all dreaded it. They saw it only through the lens of their long-established resignations: an exercise in writing independently while implementing the least amount of independence possible to remain gainfully employed.

The other three writers at this entire paper — by this time, newsrooms had begun downsizing rapidly — were writing only about the most mind-numbingly mundane topics (“Once I was on a Jumbotron”), but I saw this as the opportunity I’d been gunning for, to flex my First Amendment right. I fearlessly and — as my co-workers repeatedly said — stupidly wrote every column on controversial topics I cared deeply about, such as affordable health care, women’s reproductive rights, and education reform.

Subscriptions were canceled. Psychotic hate mail came flooding in. After we published an article about opposition to a Confederate statue, we had to lock the front door of the building for fear of a crazy asshole who was threatening to shoot us all. And then another one of my column pitches was rejected, again for fear of a lawsuit. This time, I was spirited in my rhetoric to uphold the truth to the public. I recall Byrd telling me, “We just don’t have the money to go to court if we get sued by these politicians. Rural papers are dying, and we just need to stay in business at this point.”

I recall Byrd also saying that because of his fear of libel I couldn’t write a story about the mayor of a nearby town who pulled a gun on his wife and daughter.

This, even though I had just received a mugshot of the Reno mayor that day from a trusted source, an ex-police officer also dedicated to exposing political corruption. A competitor, a digital news source, broke the story, and the next day I was fired for not “meeting” my quota on stories despite out-writing everyone there.

My termination at this rural news outlet was yet another self-fulfilling/-destructive prophecy, I must admit. For only a month before, I argued with Byrd about not being allowed to report on black mold inhalation at the Sara Lee factory which killed seven Black women. He rejected the story because many of the sources were afraid to give their names due to retaliation, termination, and police harassment, as well as a deal they accepted from the bakery to settle out of court — a deal that ended up being far less than the agreed-upon amount. Wealthy business owners who kill off factory workers do so because they know they can usually just pay their severely impoverished employees to keep quiet, especially in news deserts, where corruption grows exponentially by the day. This was another reason the women did not want to give their names, and the publisher’s policy was to never report on anything with anonymous sources as we “owe it to the community” to be accountable. Did we not owe it to the community to report on black mold leading to breast cancer and killing factory workers?

*****

By the third time it happened, I was an old hand at this game, hopefully smart enough to see it coming and quit with plenty of evidence in hand. Once again, and by God for the last time, I was the cheery girl Friday guided toward polishing vapid stories to boost morale — which I now saw clearly for what it was: a distraction from the malfeasance of powerbrokers.

This came from an editorial position at the Southlake Independent, a career choice that I must admit was fueled by a roiling hostility toward crooks of the fourth estate and an undercover investigation into what I knew would be the easiest target within a hundred-mile radius. Within a month, I discovered that publisher Fred Stovall was allowing school board members to edit my school board stories in real time. I showed screenshots of the “edits” to Editor Ronell Smith, who replied, “How much do you want to not leave?” Another call I recorded.

My story of this experience was published almost exactly a year ago today in our little operation here, an ethical endeavor I found at long last. Surprisingly, the Weekly was the only publication interested in my story of abject corruption in local government. And we’re still rolling.

It’s so weird how the massive amount of corruption in Texas used to shock me and how now it’s the honest goal of an ethical publication. Life can be funny that way sometimes. And by “funny,” I mean “sad.” But as long as I can keep exposing the pesky truth about what’s going on around here, I try to stay cheerful. Only now it’s cheerful for real. And, as always, with a side order of “fuck you” to the fraudsters.

This column reflects the opinions and fact-gathering of the author and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. He will gently edit it for clarity and concision.