A noticeably frustrated Cody Neathery prompted my greetings with a disclaimer.

“Sorry, if I sound salty,” he said as he gestured toward piles of lumber and unopened appliances, “but does that look like it’s ready to open in one week?”

His unfinished bar was weeks behind its scheduled opening date of early June. As we chatted, several workers moved and unwrapped equipment. Neathery’s team had gutted and cleared recently shuttered High Top Pub & Grub just south of downtown, but much of the renovations and finish-out for Neathery’s business was missing or unfinished.

Neathery, a Weekly contributing writer and partner in three North Texas bar concepts, said Jackie O’s is his first attempt at having full creative control over one of his bars. He recently brought on general manager Derrik States to handle much of the day-to-day work of running Fort Worth’s newest gay bar and the first local watering hole to pay homage to President John F. Kennedy and wife Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who spent the night together in downtown Fort Worth the day before his assassination in Dallas. On a back patio, States leaned into Neathery’s ear.

Photo by Edward Brown

“The ice machine won’t be here for a week,” States said. “Dishwasher should arrive in the next 45 minutes.”

Neathery told me construction requires executing steps in a particular order, meaning any late contractor or missing piece of equipment causes a cascade of delays. The owner told his crew that he was going to pick up a small fridge from Cowtown Restaurant Supply as we hopped in his beat-up red truck.

“If you have a large sum of money that you are willing to flush down the toilet, then you can open a bar or restaurant,” he said as we cruised the North Side.

The statistics for any business primarily serving alcohol aren’t encouraging. Finding consensus on those figures is difficult, but most experts and studies report around 75% of watering holes close within their first year. And those that survive may never find easy profitability. Fort Worth’s pubs and restaurants, like similar establishments across the globe, were hit especially hit hard during the pandemic.

Tens of thousands of waiters and bartenders here and across the country left for new careers during 2020 and 2021. The national restaurant industry lost around $250 billion in expected revenue during 2020, based on reporting by TIME. Even with those challenges, the number of local bars and restaurants rose throughout the pandemic, based on data from the city, with 2,726 restaurants (up from 2,287 three years ago) and 719 bars (up from 637 in 2019) currently open.

States said workers who left brought their hard-earned skills to a wide range of careers.

“I was one of those who initially left the industry,” he said. Food service workers “develop skills that are translatable to other fields, like the ability to multitask, self-manage, collaborate with other people, present professionally, and put in hard work.”

Photo by Edward Brown

Bartenders, waiters, GMs, and venue owners readily agree that the bar and restaurant industry remains drastically altered from COVID and the resulting upheaval of logistics and the workforce, but while other sectors of the economy have largely returned to pre-pandemic operations, many local pubs and dining establishments struggle to staff their businesses or attract customers. Through private conversations, the folks who tend bar and wait tables say there’s a small but significant percentage of potential customers who haven’t returned to dining in, whether that’s due to public safety concerns or a preference to eat at home.

In an email, a spokesperson with the Texas Restaurant Association said many dining spots across the Lone Star State are struggling to staff shifts.

“Restaurants continue to rebuild from the pandemic despite historic cost increases and labor shortages,” the spokesperson said. “An estimated 67% of Texas restaurant operators do not have enough employees to meet existing demand. This shortage, coupled with an 11.5% increase in wholesale food prices, creates a real challenge for even the busiest restaurants.”

Still, many areas of the city are once again bustling, like Mule Alley in the Stockyards, the West 7th corridor, and the Near Southside. Veteran bartender Jackie Roy said many dining and drinking establishments struggle due to poor management that can’t be blamed on economic factors.

“Bad management will kill a place like a virus,” he said. Industry norms like “low hourly pay and no health insurance don’t help.”

Roy, who has worked in numerous job sectors, said the food service industry still offers friendships and memories that are hard to find in other career fields.

“I really enjoy going to work and laughing and making jokes,” he said. “You don’t get to do that in other places. I’ve laughed the hardest I’ve ever laughed in a walk-in freezer. Bartenders are part of a community.”

*****

Partly inspiring this story was a text message from Cyrus Rodriguez, the long-time area bartender and barback who helped launch Birdie’s Social Club last fall. Rodriguez alleged the West 7th restaurant’s owner, Bryan Lee, did not notify workers before drastically cutting their hours.

After working five to seven days a week, Rodriquez noticed that management assigned him only a handful of shifts during colder and rainier weather in November.

“Towards the last week of November, I tried to log into our scheduling app to see about more shifts to work,” Rodriguez said, referring to Sling. “I could no longer access the app. It would say that I’m no longer part of any employee team. I immediately texted [Lee] to see what’s going on, and he never responded.”

Rodriguez alleges that Lee’s wife, whom he tried to text as well, blocked the bartender’s number.

“Then I go to try to text [Lee], and he blocked my number as well,” Rodriguez claimed. “They have left me high and dry with no work or no reasoning or explanation. They didn’t even have the decency to let me know to [look] elsewhere for work. That is just not the way to run a business or treat employees who have been there since Day 1 to help the business grow and thrive.”

In an email, Lee said he is not able to discuss personnel information out of respect for the privacy of employees.

“We have a third-party [human resources] company to support all of our staff, and we take pride in our open-door policy,” he said. “In regards to available shifts, we do our best to provide opportunities for all. With being a business that can be severely affected by cold weather and rain, our shift availability can change on a weekly basis, and we communicate this regularly with our staff.”

Rodriguez’ frustrations highlight an ongoing disconnect between many food service workers, who see their earnings as unreasonably volatile, and owners/managers who characterize many workers’ expectations as unrealistic. Several owners of bars and food trucks privately confided a belief that twentysomethings in particular are more unreliable and less willing to put in long hours than older generations.

Hao Tran, owner of Hao’s Grocery & Cafe, said she struggled early on to find consistent staff to work her smallish Asian grocery store on the Near Southside.

“We initially had a lot of interest,” Tran said. “We didn’t have many people show up for interviews. I think we had five or six people send emails back. They didn’t follow up. I set a time, and they did not show up. That was two months ago.”

The expanded and extended unemployment checks during COVID left many workers feeling too entitled, she said.

Photo by Edward Brown

Business owners, she said, treated the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) like “a gift card — some businesses took loans and said, ‘Oh, we are going to close down. We don’t have to pay it back.’ ”

Tran has had some luck hiring high school students, but many teens bristle at the $15-an-hour wage that Tran said is the most she can offer.

“They want more,” she said. “Before COVID, our salary was $10 an hour. The student I had was happy to have it. The job is not hard. It is a small local foods market.”

Tran, who also works for the Fort Worth school district, said many of her students make $20 and up working for their parents in roofing, contracting, automotive, and plumbing.

“During COVID, those kids went out and had to work to sustain the family,” she said. “Now these kids have been in the workforce. They are used to making more money. Jobs offering $12 and $15 an hour are not enough for them.”

Tran said she has seen many restaurants cut back on hours of operation, likely because staffers are less willing to work slow Sundays and Mondays. Now that her staffing issues have subsided, the grocery owner said her biggest challenge is dealing with the city’s permitting department, which she said can be slow to respond and often fails to coordinate efforts with other city departments.

COVID changed the food industry, she said, but not everyone left the sector entirely.

“I know people who food blog” and live off sponsorships, she said. “I know people who do ghost writing for chefs or writing recipes. The digital world has changed the food world. The labor part is where the struggle is.”

Bartender Roy said the exodus of experienced waiters and bartenders during 2020 and 2021 had a huge impact on the industry which can still be felt.

“I had a lot of friends leave,” he said. “Once you’re out, it’s tough to go back. It’s not a forgiving job. You are on your feet all the time, and there are not a lot of breaks. You have to love it. There was so much uncertainty during the pandemic. It was scary.”

Roy saw many of his friends pursue careers in the arts or health and fitness. Beyond the loss of many veteran bartenders and waitstaff, Roy said restaurants and bars have to contend with changes in consumer behaviors.

“I’ve noticed people aren’t willing to go out as much,” he said. “A small percentage isn’t willing to go out to fine dining anymore. When someone can grab something quick, that helps. People are less willing to take the time to go down and sit and spend a ton of money.”

Photo by Edward Brown

The veteran bartender said he hears complaints about millennials and Gen Z suggesting they’re lazy and less willing to work their way up than past generations.

“I don’t think they’re lazy,” he said. “They know their worth.”

States agrees while acknowledging that every age group has its share of slackers.

“I think those stereotypes are bullshit,” he said. “I will not mince words on that. I do not think there is a labor shortage. I think there is a shortage of positions that are willing to pay appropriately for the labor they expect or there is a toxic work culture that people will not put up with anymore.”

After many veteran food service workers left the field, teens and twentysomethings began filling those openings, he added.

“There has been some learning curves and bumps,” he said. “The labor pool is less qualified, which can come off as being lazy. This is the question I would ask managers who complain about new hires: Have you taken the time to train, support, and mentor these workers? If an employer has felt that they have done that, then it is fair criticism, but to make a broad sweep about my [millennial] generation and the generation after me” is bogus.

*****

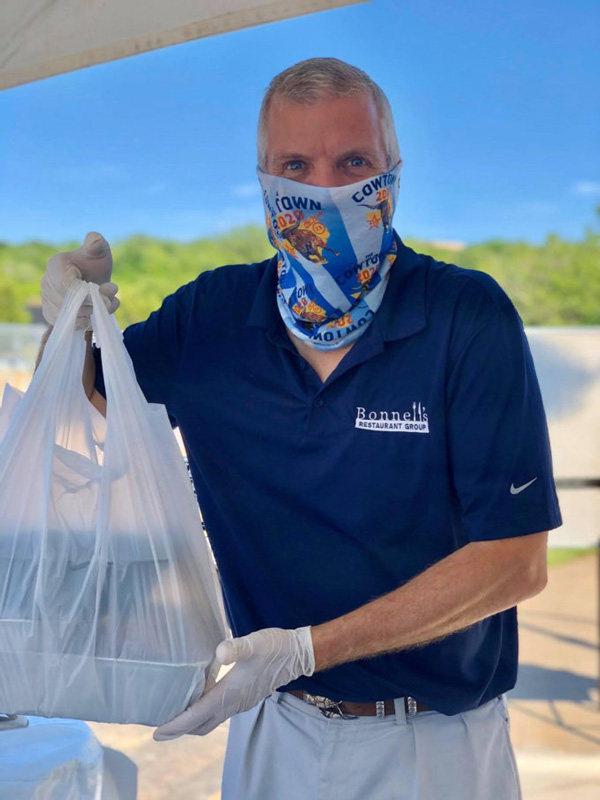

Tran said restaurants that can provide convenience and value with fewer employees will have an advantage in the post-pandemic environment. She points to Chef Jon Bonnell’s drive-thru pickup service for $40 family meals at Bonnell’s Fine Texas Cuisine as one example.

“I think that was a brilliant idea to get him through COVID,” she said. “Now it is here to stay. Online ordering for pickups has changed my world. It’s convenient for people, and it reduces traffic into a store. For me, I don’t want to go to a store anymore. I will get online and order groceries and pick it up.”

The trend toward not dining in, she said, means there are fewer reasons to tip, which can drive down food service wages.

“If you are picking up something, you tend to tip less,” she said.

The bar and restaurant industry, she added, is evolving, and consumers should be mindful that mom-and-pop stores drive our local economy.

Photo by Edward Brown

“Support small businesses,” she said. “That is your bread and butter around here. They pay local taxes. We cannot survive without community support.”

Even with the challenges of staffing her small business without the benefit of a marketing budget, Tran said it’s the love of people that keeps her in the industry.

“It is not about the money,” she said. “It is about the love of the food and serving people. I love to eat. Food is social. Without that, for me, I might as well as go to therapy. We need that human interaction.”

States believes his team will weather any challenges that arise, especially with the support of queer locals and their allies.

“We are joining a community,” he said, looking across the street to queer-friendly Liberty Lounge, a bar that “is truly inclusive. That is what our community is all about. As much as queer spaces can be safe, they can also be divisive. [Liberty Lounge owner] Jenna Hill-Higgs is one of the most politically active people in our community. She has done so much to support the Near Southside and Fort Worth in general. We are excited to be the new kid on the block, especially during Pride Month. We are here because a lot of people paved the way for us to be here.”

Neathery said Fort Worth has long needed another gay bar and Jackie O’s will be a quirky cocktail lounge that’s a little “swanky and a little skanky.” In addition to a sex toy vending machine, the bar will have a set cocktail menu that includes the former First Lady’s favorite drink: a negroni with a twist. States said several drinks will have risqué names.

“We have a drink called Just the Tip that’s made with phallic ice,” he said. “It’s quite a, um, stiff drink.”

States and Neathery’s commitment to providing a safe and respectful work environment — both for customers and employees — makes good business sense, and it’s just the right thing to do.

As for the pre-COVID days that many bar and restaurant owners pine for, those days are gone.

“There is no returning to what it was,” States said. “The world and food service industry has changed in such a profound way that there’s no path directly back. Whatever we’re becoming is different. We have done an amazing job of showing our resilience as an industry. If you are doing your best to be a good concept and leader, that’s all you can do at the end of the day. If something better comes along for my staff members, I’m not going to have hard feelings about that. I want my staff to be happy and fulfilled just as I want that for myself, my friends, and my family.”

More than three years after the pandemic, nightlife is once again alive and well, he added.

“Bar programs are returning to having the chance and capital to be innovative again,” he said. “We’re back at a point where we can celebrate what we’re doing and how we’re doing it instead of worrying about being able to do it at all.”

Courtesy Facebook