All the obituaries for Vernon Fisher are using the words “blackboard” or “chalkboard.” It is true, many of the artist’s works feature an off-black background festooned with smudges of white that recall the classroom slates of olden days that would need their chalk marks wiped imperfectly clean at the end of the day. Against those, he would place incongruous splotches of color, doodles of Mickey Mouse or Richard Nixon, or cartoon characters imagining the Hindenburg disaster and freaking out. Those so-called “blackboard paintings” wound up being Fisher’s calling card in museums all over the world.

The Fort Worth-born artist who taught for decades at UNT died at the age of 80 on April 23. In a bitter irony, his passing came a few days before the premiere of Breaking the Code, Michael Flanagan’s documentary film about him, at the Dallas International Film Festival and the Thin Line Film Festival last weekend. (DIFF is holding an additional screening today.)

Fisher was born on February 19, 1943, in Fort Worth and spent much of his childhood in Granbury. In our profile of him after his retrospective at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (“How Vernon Fisher Came to K-Mart Conceptualism,” Oct. 27, 2010), he admitted he hadn’t given serious thought to a career in art during his formative years, instead going out for sports like so many other young men in his hometown.

“I tried to be a very normal kid,” he said. “In small-town Texas, there’ll be 60 people in your class, and you’ll know everybody. There’s a lot of pressure to fit in, and you really don’t have that many choices.”

He attended Hardin-Simmons University in Abilene, where he initially was a math student. He eventually received an English degree in 1967, but he stayed there another year to pursue his vocation as an artist.

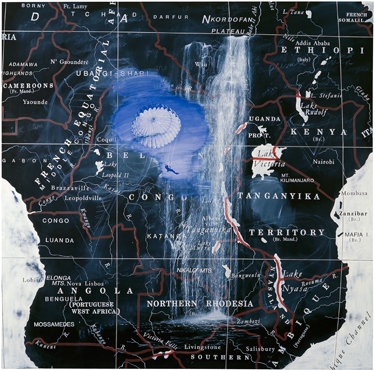

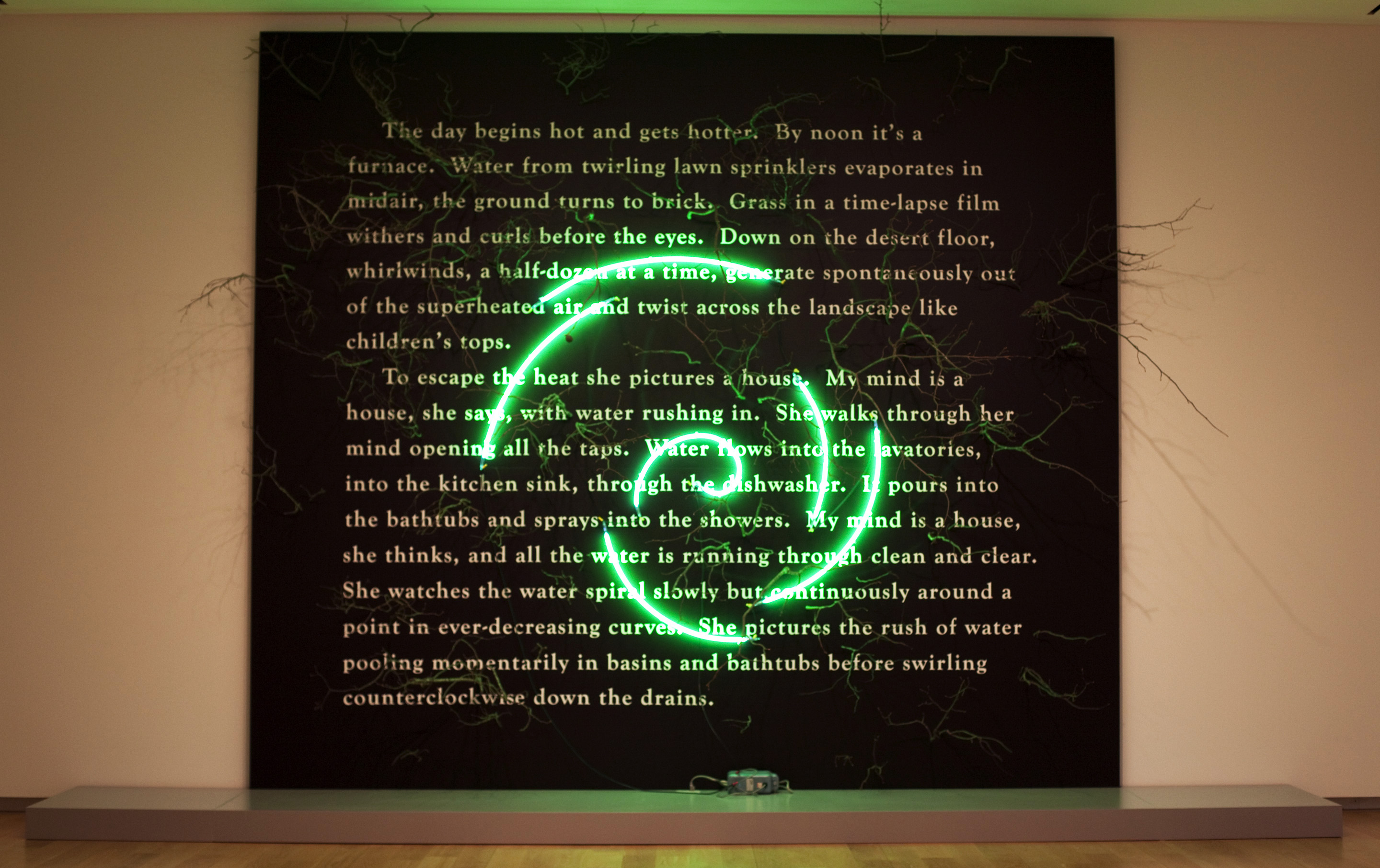

He earned an M.F.A. at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign during the only substantive time he spent outside the Lone Star State. Much of the press coverage has concentrated on his decision to spend most of his life in North Texas, despite the conventional wisdom of his youth that said artists had to live on one of America’s coasts to build a career. Fisher proved them wrong, as his works in various media found their way onto the walls of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Guggenheim Museum (New York), the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts (Houston). His 1987 installation “Coriolis Effect” is part of the Modern’s permanent collection.

While his earliest works were in an abstract vein, he rejected the modish labels of Pop Art and abstract expressionism as well as any overly neat interpretations of his art. The pop-culture characters in his work sprang from the culture of his youth without offering up direct commentary on the popular culture outside the realm of high art. His works, many of which were produced in his art studio at 1109 N. Main St., invited viewers to take their own meanings and mixed hilarity with serious themes to prevent fans and critics from pigeonholing him.

He taught for nine years at Austin College in Sherman, but he was better known for his time at UNT, where he started teaching in 1977. From that post, he exerted profound influence on Texas artists even beyond the satiric, sophisticated works that rippled far out into the world. He is survived by his wife, the fine artist Julie Bozzi.