Perhaps one of the most defining elements of civic life in the United States is the fact that the lowly citizens and residents of this country have waited, sometimes centuries, for the grand proclamations and promises made by presidents to become a reality. Take the assertion that “all men are created equal.” Within that quote from our Declaration of Independence is a willful omission of women, and which men were considered worthy of rights certainly left out enslaved and indigenous persons at that time.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art is diving into the rift between promises made and kept. For Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation, museum staff chose seven contemporary Black artists to produce work to display alongside a handful of Civil War-era pieces. The result is thought-provoking and often unsettling, forcing us to question our assumptions about the state of race relations in the United States nearly 160 years after the Civil War.

Greeting viewers is John Quincy Adams Ward’s “The Freedman.” The sculpture from shortly after Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation perfectly anchors the show in the past. Seated on a tree stump, the muscular Black man leans his left elbow on his left knee, resting but poised to rise at a moment’s notice. He holds a shackle in his right arm that has been broken or released from his left wrist. The man looks neither up nor down but directly at museumgoers as if demanding their engagement.

In the next room, Hugh Hayden’s “American Dream” could be a contemporary version of “The Freedman.” While the rested yet restive pose of Ward’s former slave remains, Hayden’s figure, rendered in white 3D-printed plastic, is seated on a wooden lawn chair while wearing a collared short-sleeve shirt and presumably khaki pants. The trappings of modernity are everywhere, but the immutable pose that mimics the 1863 piece suggests that the updated window dressing is not the point. Hayden’s man may be free, but by adopting a similar pose, he is still tied to an oppressive history.

Letitia Huckaby has long focused on the legacy of freedmen’s towns and the stories of the offspring of enslaved men and women throughout the Deep South. For Emancipation, the Fort Worth multidisciplinarian presents four large works printed on cotton fabric. The black shadows of former human cargo of the Clotilda — the last slave ship to reach U.S. shores, in 1860 — overlap ornate floral and decorative patterns. Descendants of Clotilda founded Africatown, near Mobile, Alabama, and Huckaby’s work beautifully ties past to present while reminding viewers that those trafficked men, women, and children were the labor behind the textile industry at the time.

“The definition of emancipation that strikes me the most is the fact or process of being set free from legal, social, or political restrictions,” Huckaby says in her artist statement.

Maya Freelon, known for vibrant tissue-paper art, has created a site-specific installation. On one interior wall, she laid out dozens of colorful squares in clear lines and rows. On the opposite wall is a vibrant protruding collage that spills downward toward the center of the large gallery. Among many American cultures, quilting was a means of preserving history by cutting up bits of family linens or incorporating more literal images and words onto the knitted blankets that are handed down for several generations. By invoking the quilting tradition, Freelon’s “Fool Me Once” reminds viewers that the past is intricately tied to the future, as the overall show so beautifully lays out.

Jeffrey Meris’ kinetic sculpture conveys torture. The crude automatic pully system of “The Block Is Hot” slowly lifts a white plaster torso up and down, leaving a fine layer of white dust on the museum’s floor. During a recent talk organized by the curators, Meris said the centerpiece is from a cast of his own body. He recalled being detained by New York City police a few years ago for jumping a subway turnstile after several unsuccessful attempts to swipe his prepaid card. The police falsely described Meris as several inches taller and many pounds heavier than his actual size, something that struck him as emblematic of the general misperception by Americans and law enforcement that Black men are innately physically threatening.

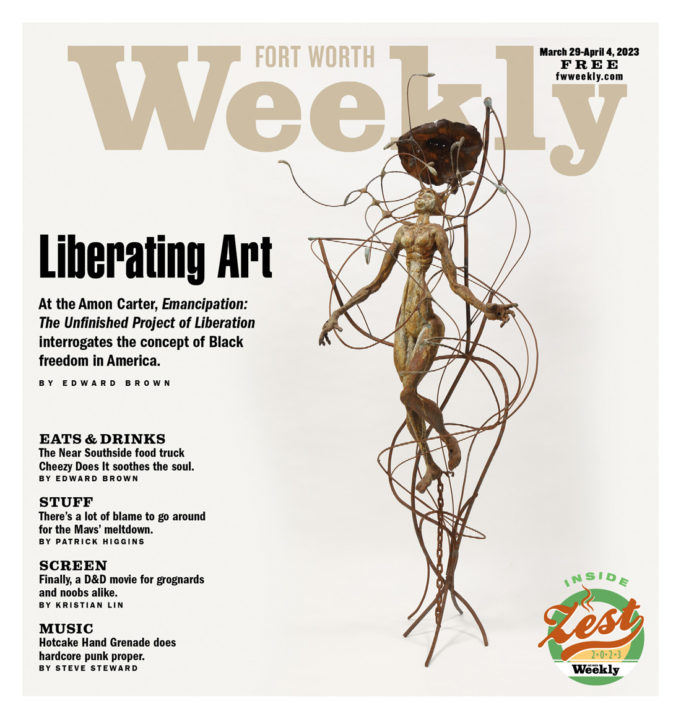

Toward the end of the show is a striking sculpture by Alfred Conteh. In “Float,” a buoyant female figure covered in rust and decay appears to be floating upward even as rusty chains bind her feet to the ground. Her wide-brimmed hat suggests she has left a church service or another festive or solemn occasion, but there is little else to indicate where or when she is from, which lends a sense of purgatory to the work.

One-hundred-and-sixty years later, Ward would recognize many of the racist dynamics of his time still at play now. Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare, for example, built his political career demonizing and dehumanizing Hispanics and Blacks, and Texas continues to lead the nation in censoring honest public school discussions about this country’s sordid history of institutionalized discrimination under the guise of combating Critical Race Theory.

Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation is brilliantly successful in reviving uncomfortable parts of this country’s history — not simply as an artistic compass showing where we’ve been but rather as a subtle and thoughtful reminder that America is arguably no closer to delivering on its promise of Black liberation than it was in 1863.

Emancipation: The Unfinished Project of Liberation

Thru Jul 9 at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, 3501 Camp Bowie Blvd, FW. Free. 817-738-1933.