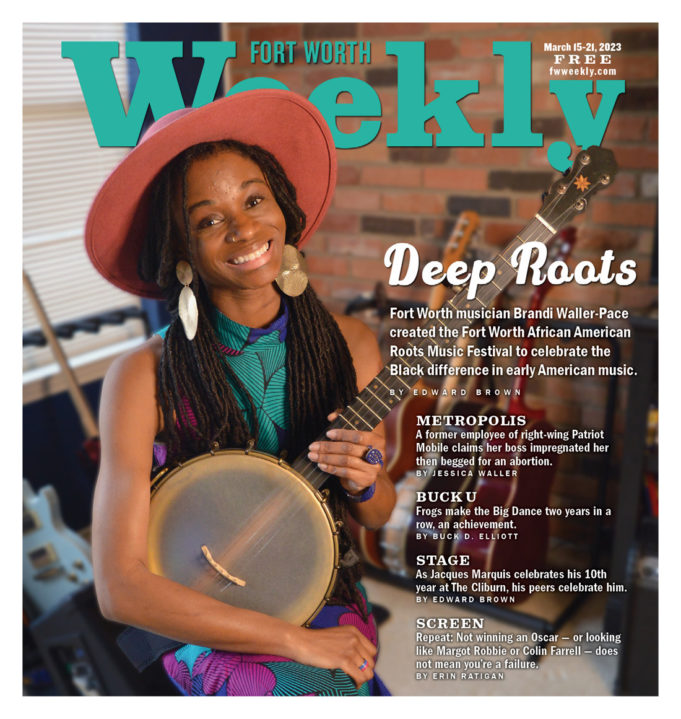

When Brandi Waller-Pace left her hometown of Atlanta to study jazz at Howard University in 2002, she did not know that journey would lead to a career in scholarly research on and advocacy for the often-forgotten role of Black musicians in shaping American roots music.

“Looking back, I was always talking about activism,” she said.

Howard offered an opportunity for the composer and multi-instrumentalist to study and perform in a largely all-Black environment.

“There were so many seeds planted,” from that time, she said. “If I didn’t have that security, I would not have had the foundation to do what I do now. I think I would have questioned myself.”

Courtesy FWAAMFest

Piecing together the history of Black contributions to early blues and American folk music required researching the past by working with museum scholars and documenting the oral and musical traditions of songs. Descriptions of those tunes and performance techniques, she found, had been passed down for generations from families who trace their lineage to formerly enslaved ancestors.

The culmination of that research led to the inaugural Fort Worth African American Roots Music Festival (FWAAMFest) online in 2021. Waller-Pace has since hosted the events at Southside Preservation Hall on the Southside, including this year’s iteration on Saturday.

“What I’m able to do [with the festival] is a culmination of my life’s experience,” she said. “Sometimes, I learn about a song because we sat in a circle and someone said this song is from this time. The old-time tunes I play are from the 1800s or from someone who wrote it last week.”

Saturday’s performances feature more than a dozen notable musicians and ensembles, including Grammy-nominated multi-instrumentalist Hubby Jenkins, singer-songwriter Justin Golden (famed for his renditions of fingerpicked Piedmont blues), and Southern Soul singer-songwriter Rissi Palmer. Waller-Pace said having an all-Black lineup performing roots music is an important step for reclaiming genres of music often appropriated by white-owned record labels throughout the 20th century.

Beyond performances, education is an important component of FWAAMFest, Waller-Pace said. After teaching elementary music education for 11 years in the Fort Worth school district, the music advocate left teaching early on during the pandemic to focus on her career and doctoral studies at UNT. Her time as a teacher revealed how public schools often fail to give an accurate and well-rounded account of culture and music history.

“The assumptions of the training were still Western European-centric,” she said. “We had students from the Middle East. The tonalities [their culture used] were considered too complicated for kids. The music examples we used would alter their tonality to what Western ears would call less complicated. The baseline for what they taught kids was from dominant white culture.”

The oversimplified narrative used to teach music history in schools often relegated Black contributions solely to R&B, blues, and jazz. FWAAMFest is part of a broader effort by Black scholars and activists to remind Americans that Black culture shaped American roots music in powerful and beautiful ways, she said.

Waller-Pace still remembers seeing historic descriptions of American music that rarely portrayed the Black originators of folk music.

“I wasn’t at the core of what was considered valuable. I noticed in my classroom, a lot of times my students saw a banjo [played by white people]. It is an American instrument, but it has cousins in Africa. We are of African descent. The banjo story is very parallel.”

Fort Worth African American Roots Music Festival

Noon at Southside Preservation Hall, 1519 Lipscomb St, FW. $20-50. FWAAMFest.com.