It’s Black History Month, and we just watched a Super Bowl. There were Black players and white players but mostly Black. And it was OK.

I mean, at least people who look like me — white — didn’t go out and kill a bunch of Black people for getting excited about it.

It wasn’t such a big deal — but it used to be.

Especially here in Texas.

*****

Ten years ago, I wrote a story about an act of genocide in East Texas. It was titled “Town’s 1910 Racial Strife a Nearly Forgotten Piece of Texas Past,” and it appeared in the Feb. 22, 2013 edition of the Austin American-Statesman. In the days and weeks that followed, I was contacted by Christen Thompson of The History Press, and she offered me a book deal.

I’d never written a book. I’d never even thought about writing a book, and I was reticent, to say the least.

First, I didn’t know if I was capable of writing a book. Second, no one had ever written a book on the subject, and I wasn’t sure there was enough information or research available to even complete a book-length manuscript on the topic. Third, the subject involved a massacre of innocent Blacks — and I am a white man. I thought that surely some Black graduate student or academic was pursuing it.

I researched the subject on the internet. I perused relevant academic journals online. I couldn’t find anything. I told Thompson, who is also white, that I wasn’t sure I was the right person to write the book. She pointed out that I’d already written about the pogrom for a major newspaper and it was honest and well-received. She wasn’t wrong.

The “1910 Racial Strife” piece attracted the attention of some of the descendants of the Rosewood Massacre in Florida. The Rosewood Massacre of 1923 had already received film treatment, but they approached me about writing a book about it. I politely told them that I didn’t feel comfortable with writing about something that happened so far away, in another state, and thanked them for their interest. Then, I was contacted by a descendant of someone involved in the carnage I’d written about in the Statesman but not a descendant of a Black victim — an ashamed descendant of one of the white perpetrators.

The book that I wound up writing about this atrocity was The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas.

*****

By the early 20th century in the Slocum area of southeastern Anderson County, several Black citizens were considerably propertied, a few owning stores, businesses, and more. The rocky Reconstruction period after the Civil War was over, and some African Americans, previously born into slavery, had established footholds in the local economy. The Holley and Wilson families, for example, apparently owned one of the community’s only general stores and hundreds of acres of rich farmland.

This alone, in parts of the South, would have been grounds for white violence, but in the Slocum area, which included the small communities of Percilla (Houston County), Alderbranch, Denson Springs, and the “negro colonies” of St. James and Sandy Beulah, there were other issues. In early May 1910, a white regional road construction foreman named Enoch Williams put Abe Wilson, a Black man (the Wilson partner of the local general store and related to the Holleys by marriage), in charge of rounding up help for local road improvements, and a white man named Jim Spurger was infuriated. On May 20 or 23, Spurger showed up for road repairs with a gun and refused to help. He contributed one dollar for the day’s work and said he would join the effort “when we get a white man for an overseer.”

At a Juneteenth picnic on June 19, 1910, a white man named Reddin Alford troubled Marsh Holley over a bank note, and frustrations lingered. The following day, a Black man named Leonard Johnson was seized from the sheriff of the next county over (Cherokee County) by a mob of 150 white men and burned at the stake — no trial, no jury — for the alleged rape of a 17-year-old white girl named Maudie Redden. And several Cherokee County Blacks who believed Johnson was innocent “were beaten,” “otherwise harshly treated,” and, according to some accounts, murdered by the mob.

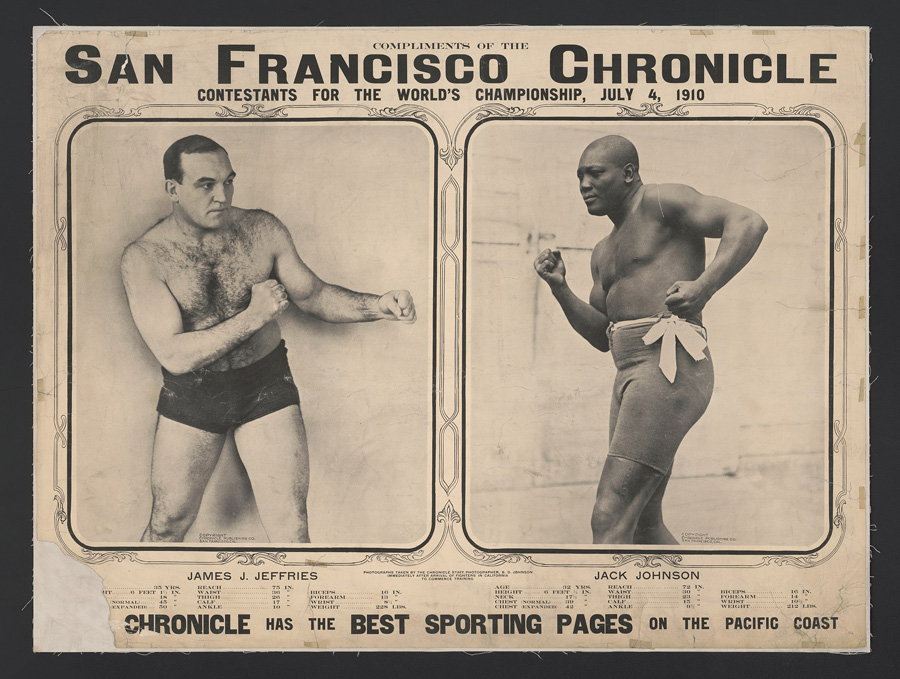

Then, when Black Galveston native Jack Johnson pummeled “Great White Hope” Jim Jeffries to remain the world heavyweight boxing champion in early July 1910, many whites construed the pride that Johnson’s victory inspired in African Americans as “uppity” behavior and general disrespect.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Jim Spurger began openly fomenting white discontent. Wild rumors began to circulate, suggesting that local Blacks were planning an uprising, and racist malcontents manipulated the local white population.

On Wednesday, July 27, 1910, Abe Wilson’s house was burned to the ground, and by Friday, July 29, 1910, white hysteria had transmogrified into a cold-blooded, murderous white rampage.

Goaded by Spurger and others, hundreds of white citizens from Anderson and the surrounding counties converged on the Slocum area armed with pistols, shotguns, and rifles. That morning, near Sadlers Creek, they fired on three young African Americans headed to feed cattle, killing 18-year-old Cleveland Larkin and wounding 15-year-old Charlie Wilson. The third, 18-year-old Lusk Holley, escaped, only to be shot at again later in the day while he, his 20-year-old brother Alex Holley, and their friend William Foreman, were fleeing to Palestine. Alex was killed, and Lusk was wounded. Foreman ran for his life. Lusk pretended to be dead so a group of 20 white men wouldn’t finish him off.

For the next two days, white mobs reportedly marched through the area gunning down an unknown number of Black Texans. A 30-year-old African American named John Hays was found dead in a roadway and 20-year-old Sam Baker was shot to death in Dick Wilson’s house. Dick Wilson (Charlie Wilson’s father), his son Geffy Wilson, and a 70-year-old named Ben Dancy were killed while sitting with the body the following day.

In addition to the Anderson County murders, which occurred near the county line, Will Burley was killed just south of the line in Houston County. And he wasn’t the only one. According to contemporary newspaper accounts, white mobs traveled from house to house in Anderson and Houston counties, shooting African Americans who answered their hails and slaughtering more while they tended their fields.

Almost every early newspaper report on the transpiring bloodshed in and around Slocum portrayed the African Americans as the aggressors, indicating that the local white community was simply defending itself. These accounts were gross mischaracterizations. When Anderson County District Judge Benjamin H. Gardner closed saloons in Palestine and ordered local gun and ammunition stores to stop selling their wares on July 30, it was not to stop a Black uprising. It was to defuse what the Galveston Daily News called a one-sided “reign of terror” characterized by “a fierce manhunt in the woods” and resulting in bullet-riddled Black bodies everywhere.

When reporters gathered on July 31, up to two dozen murders had been reported and dozens more were suspected, but local authorities had collected only eight bodies. Once the carnage had begun, hundreds of African Americans had fled to the surrounding piney woods and local marshes, and by the time the Texas Rangers and state militia arrived, there was no way to estimate the number of African American dead.

On Aug. 1, a few Texas Rangers and some locals gathered up several African-American bodies and buried them (wrapped in blankets and placed in a single large box) in a large pit four miles south of Slocum. Some reports suggest the unmarked mass grave was full of dozens of corpses, because law enforcement just kept coming back out of the woods with more bodies. Farther north, Marsh Holley was found on a road just south of Palestine. He begged the authorities for help, requesting that he be taken to the county jail for his own protection.

*****

After the first several murders, most members of the African-American community began fleeing, but this didn’t stop the white mobs. Most of the victims were shot in the back. Two bodies found near the former town of Percilla still had travel bundles of food and clothing at their sides.

Anderson County Sheriff William H. Black said it would be “difficult to find out just how many [Blacks] were killed” because they were “scattered all over the woods.” He also admitted that buzzards would find many of the victims first, if at all.

With the arrival of the press — and after early attempts at spinning the news reports to portray the African-American victims as armed insurrectionists had failed — the guilty parties engaged in damage control. Some of the transgressors returned to the murder scenes to remove the evidence of their crimes. Some threatened potential witnesses and fellow perpetrators if they “crawfished,” but, regarding the official narrative, Sheriff Black was unequivocal.

“Men were going about killing Negroes as fast as they could find them,” he told The New York Times, “and, so far as I was able to ascertain, without any real cause. … These Negroes have done no wrong that I can discover. I don’t know how many [whites] were in the mob, but there may have been 200 or 300. Some of them cut telephone wires. They hunted the Negroes down like sheep.”

According to the local law enforcement leaders on hand at the time, eight casualties was a conservative number. Sheriff Black and others insisted there were at least a dozen more, and some reports suggest there may have been dozens if not hundreds more. Some witnesses counted 22 casualties. Elkhart native F.M. Power said there were 30 “missing negroes.” Slocum-area resident Luther Hardeman claimed to have knowledge of 18 African-American casualties, and that’s the original number reported by the Galveston Daily News and The New York Times (on July 31), but the body count seemed to shrink as the pogrom’s publicity grew.

When a Galveston Daily News correspondent visited Lusk Holley and Charlie Wilson on July 31, Wilson said he had recognized two of the assailants during the first shooting on July 29. Holley said that after he had been wounded in the second shooting later in the day, a different group of white men had come upon him while he pretended to be dead. He said he recognized the voice of a prominent local farmer named Jeff Wise, who deemed his apparent and his brother’s actual death “a shame” as he passed by.

The Black corpses scattered all over the area were being disposed of and the perpetrators of the bloodlust were making themselves scarce, so Judge Gardner made a tough decision. Instead of waiting for the proverbial dust to settle, he decided to arrest the suspects he could and charge them with the murders they could immediately prosecute — before all the evidence and any more of the suspects disappeared.

At the initial grand jury hearing, a large percentage of the remaining Slocum residents were subpoenaed. Some residents refused to testify and were arrested. Judge Gardner told the all-male, all-white jury that the massacre was “a disgrace, not only to the county but to the state” and that it was up to them to do their “full duty.”

According to the Aug. 2 edition of the Palestine Daily Herald, Judge Gardner attempted to clarify the charges and the issues at hand, explaining various statutes to the jury. He specifically noted that even if there had been threats or conspiracies “on the part of any number of Negroes to do violence to white persons, it would not justify” vigilantism. “The law furnishes ample remedy,” Gardner continued. “There is no justification for shooting men in the back” or “waylaying or killing them in their houses.”

When the grand jury findings were reported on Aug. 17, several dozen witnesses had been examined. Though 11 men were initially arrested, seven were finally indicted, including Isom Garner, B.J. Jenkins, Steve Jenkins, Andrew Kirkwood, Henry Shipper, Curtis Spurger, and Jim Spurger. Only Kirkwood was immediately granted bail, and another, Alvin Oliver, turned state’s evidence. Two cases moved forward, one based on killings in Anderson County and one involving the murder of Will Burley in Houston County. No one was ever indicted in the deaths of John Hays or Alex Holley, and no other victims were ever verified.

In the weeks and months following what came to be known as the Slocum Massacre, the local Black residents made a mass exodus, leaving homes, properties, and businesses behind. And that was fine with most of their white neighbors, whether they were perpetrators or bystanders.

On Nov. 14, 1910, the defendants in the Houston County case (Jim Spurger, Isom Garner, Andrew Kirkwood, William Henry, B.J. Jenkins, and Henry Shipper) were arraigned, and each pleaded “not guilty” to the charge of first-degree murder. The presiding judge denied bail to every defendant except Shipper. His was set at $5,000, and his family and friends put up their lands and properties as his surety.

On Wednesday, Dec. 12, the defendants in the Anderson County case were arraigned, and Judge Gardner, on his own motion, announced the trial venue would be changed to Limestone County unless the attorneys for both the state and the defendants agreed to a different location in the counties of Navarro, McLennan, Williamson, Travis, or Harris. Judge Gardner preferred Navarro, but the attorneys for the state and the defendants agreed on a venue in Harris. This was very fortuitous for the defendants. The front-page Houston Post headline after Jack Johnson defeated Jim Jeffries read, “Ebon Gloom Loomed Deep As Negro Trounced Jeff,” and the lede was quite telling:

The ebon complexion of the world’s champion had nothing on the gloom that settled over Houston yesterday after the flash came that Johnson had knocked out the white man. The gloom settled down in such large squares, oblong and chunks as to be almost opaque.

And if you think that was an exaggeration of white despair (and desperation), consider this clip in the Honey Grove Signal three-and-a-half weeks later, on the day the killing began in the Slocum area:

Suppose a South African Gorilla had come over to the United States, put on store clothes, walked up to Jim Jeffries and demanded a fight. Would Jeffries have displayed any brains by recognizing him? He would have said to the gorilla: “You are not in my class. I shall keep my part of American sport in the human family.” And that’s exactly what he should have said to the big sifter-footed, liver-lipped burr-head who paralyzed him and pulverized him at Reno the other day.

The Lord knows the negro race was impudent enuf [sic] prior to the Johnson victory at Reno. You can scarcely pick up a newspaper without reading where some negro has been mobbed for his meanness. There are a lot of cerulean bellied yankee aristocrats who insist on referring to the coon as “Mistah” and the coon forthwith proceeds to rape some white woman or little girl. As long as the negro was a slave, he was harmless, for he realized that there was a great gaping hiatus yawning between himself and the white race and he cheerfully kept his post. The old “befo de wah” slave nigger had no more notion of breeding with a white woman than a monkey would breeding with a swan.

Appalling, yes, but, to be fair, Honey Grove sits between Bonham, Texas, where local whites and lawyers pilfered the massive land bequeathment of Thomas Bean from his extended Black heirs in multiple litigious scams during the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and Paris, Texas, where at least four Black men were burned at the stake from the Civil War era to 1920. But the citizens of Honey Grove did burn their own Black man at the stake in mid-May 1930.

Which draws our attention back to the lynching of Leonard Johnson, just two weeks before Jack Johnson “pulverized” Great White Hope Jim Jeffries. The 17-year-old white female whom Johnson was accused of assaulting and murdering was the daughter of W.H. Redden, constable for Precinct 6 of Cherokee County, and Johnson was actually a “county convict working off a crime” at Constable Redden’s place. According to the Palestine Daily Herald, “the negro was suspicioned and arrested, and the evidence was sufficient to warrant the mob in reaching the conclusion that the right man was arrested, though he stoutly maintained his innocence.”

And the lynch mob reportedly overpowered Sheriff C.K. Norwood and 10 deputies?! Then, several African Americans in the community heard what was happening and attempted to intervene and, again, were beaten and, in some cases, reportedly killed.

Should I mention that the white mob went to a lot of trouble to avoid due process?

Should I also mention that Leonard Johnson was still working Constable Redden’s land when he was arrested? So, if the mob and the Daily Herald got it straight — Johnson returned to his work after the rape and murder to fulfil the terms of his convict labor agreement?!

In early May 1911, attorney Ned R. Morris of Palestine successfully petitioned the state’s Court of Criminal Appeals to grant bail for the defendants. On May 10, all those charged were released on $1,500 bail, and none of the indictments were ever prosecuted.

At the same time, the personal holdings of many white Slocum-area citizens increased handsomely.

The abandoned African-American properties were absorbed or repurposed as the white population saw fit. Many Black landowners were either dead or missing, and their land titles were vacated or revised. And then a fire at the Anderson County courthouse conveniently destroyed many of the original titles, so the revisions couldn’t be examined or questioned.

A racial pogrom and the resultant racial expulsion. An opportunistic white land grab. Black men burned at the stake. Black citizens cheated out of their lands and their legacies. Possibly several unmarked, mass graves, still unverified and unexhumed today. All conspicuously absent from Texas memory.

*****

The strange thing about the Slocum Massacre piece I’d written in the Austin American-Statesman in February 2013 was that I was actually researching another ethnic pogrom in West Texas when I stumbled onto the Slocum atrocity. I was looking for information on the 1918 Porvenir Massacre and kept seeing mentions of a “race riot” in East Texas a few years before. I’d never heard of or learned about either in school or college but was pretty far along in my research on the Porvenir Massacre when I took a closer look at the Slocum Massacre. It shocked me.

I’d seen Mississippi Burning and Rosewood, and I had even heard about the Tulsa Race Massacre, but I wasn’t aware that anything like that had happened in Texas. And as I perused and scrutinized the reports of the carnage in the Slocum area of East Texas, I realized something was amiss. The reporting didn’t add up.

Hundreds of white men riding and/or marching around southeastern Anderson County and northeastern Houston County (Percilla, Augusta, others) — after emptying the local gun and ammunition stores — reportedly shooting their Black neighbors on sight. And only eight casualties?

The harder I looked, the more suspicious I became. I subscribed to a newspaper archive. I discovered that a local Star-Telegram writer, Tim Madigan, had written about the massacre in 2011. His work led to Texas House Resolution 865, which officially acknowledged the Slocum Massacre on March 30, 2011. I picked Madigan’s brain. I asked for information on his sources. But after Madigan’s stories and HR865, his sources didn’t have much to say. I suspected they faced reprisals.

I accepted a book deal with The History Press, but one book became two. I asked Thompson if I could write a collection of little-known Texas stories first and publish a book on the Slocum Massacre after. The collection — originally titled Texas Curiosities — would become Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious. Including chapters on the Slocum and Porvenir massacres, it was published just eight months after my Slocum Massacre piece in the Statesman.

My book on the Slocum Massacre itself would appear just six months later, on May 12, 2014.

Two books in 14 months, published six months apart, and that after a virtual stand-up start.

I didn’t know any better.

I worked on the Slocum Massacre book while I was finishing Texas Obscurities but immediately encountered frustrating obstacles. The first descendant of the Holley family (now spelled Hollie) whom I contacted to interview referred me to a Fort Worth preacher who served as the family spokesperson. When I got him on the phone and explained that I was trying to write a book on the Slocum Massacre and needed to speak with members of the Hollie family for details and background, he had only one question: “How much?”

Courtesy of The History Press

I futilely explained that I was a freelance writer who drove a 7-year-old Nissan pickup, was not paid a book advance, was clearly not writing a book like Harry Potter or Twilight (that might make a fortune), that at that juncture I had never even published a book before, and that I was not rich or even well off. Our conversation ended succinctly but not impolitely.

I was off to a bad start already, and things grew markedly worse.

Denied access to the Hollie family, I reached out to the Anderson County Historical Commission. I got Commission chair Jimmy Ray Odom on the horn, and, when he heard what I was initially inquiring about, he was very keen on making sure I wasn’t a member of the NAACP. I assured him I wasn’t.

“I don’t truck with those folks,” he said. “They were here complaining about the Confederate flag at our courthouse a while back.”

I reassured him I wasn’t a member, and he proceeded to explain to me how there was never any real evidence supporting the notion that there was a massacre in Slocum and that the hoax was based on exaggerated newspaper reports from outside the region. I demurred and insisted I’d seen local reports detailing the bloodshed as well. We went back and forth briefly, Odom denying and me pressing, and then he got real quiet. He wasn’t getting anywhere with me, so, after a long pause, he asked me straight out: “Aren’t you a white man?”

I was somewhat taken aback, but I recovered quickly.

“Yes,” I said, “but I’m also a human being, and the folks who died in the Slocum Massacre were human beings.”

Odom didn’t respond.

“I’m gonna tell this story,” I continued, “whether y’all help me or not.”

And “not” turned out to be the case, but I caught some breaks. I found a junior college research paper discussing the massacre tucked in a “Black History” or “Slocum” file at the Palestine Public Library. It gave me more detail and listed other sources. It made me aware of Felix Green’s 2012 book The Piersons and Barnetts of East Texas, which had mentions of the massacre and family victims affected by it. Then, I realized the massacre had spread into Houston County and camped out in the Houston County court archives and then visited the Houston County Historical Commission in person.

The county chairperson was a Black woman named Barbara Wooten, and when I informed her what I was interested in looking into, she was skeptical. But once she realized I was on the up and up, she gave me access to a cache of theretofore unpublished correspondence that helped me finish the book.

******

The publication of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas turned out to be just the beginning. When Constance Hollie-Jawaid, the chief spokesperson for the descendants of the Slocum Massacre, became aware of the title and read it, she called me on the verge of tears. She was surprised by how much of the story she hadn’t been aware of and then furious at the family spokesman who discouraged me from speaking with her and the rest of the family.

Hollie-Jawaid asked me to assist her in applying for a Slocum Massacre historical marker. She sponsored the effort, and we cowrote the application. When Hollie-Jawaid submitted the application to the Anderson County Historical Commission, Odom was immediately hostile. He criticized our application, variously claiming it was unprofessional, based on rumors, antagonistic, and, finally, too focused on negative history rather than positive. Then, Odom claimed the commission didn’t have a quorum and wasn’t going to consider applications that year. After that, he insisted that the commission would have considered the application but that I, myself, had put Hollie-Jawaid up to filing the historical marker application to increase the sales of my book at an Anderson County pioneer festival that neither Constance nor I had ever heard of before.

Odom obviously didn’t know Constance Hollie-Jawaid very well.

When she had had enough of the Anderson County Historical Commission’s machinations, she appealed directly to the Texas State Historical Association, and its members agreed to consider the application independent of the county historical commission. We were off to the races (pardon the pun).

During the Slocum Massacre historical marker application process, forces from every side of the effort tried to dissuade or divide us. Some of my white friends and associates accused me of being ashamed of my whiteness. Some of Hollie-Jawaid’s Black friends and associates believed she shouldn’t be pursuing justice for the Slocum Massacre with a white man.

With the date of a decision on Texas historical markers approaching in January 2015, Hollie-Jawaid and I were beset from every direction with criticism and predictions of failure. Our white detractors acted like it was an assault on the Republic itself. Some of our Black detractors also condemned it outright or told us it would not be approved without their support.

Courtesy of Paul Beatty

Constance Hollie-Jawaid ignored them all, and on Jan. 29, 2015, the Texas State Historical Commission unanimously approved the Slocum Massacre historical marker application with a score of 98 on a 100-point scale. When it was placed and dedicated on Jan. 16, 2016, it became the first state of Texas historical marker to specifically acknowledge racial violence against African Americans.

Hollie-Jawaid and I were elated and, on some level, relieved, but we both knew there was still work to be done. Over the next several years, we tried again and again to bring attention to the unmarked mass graves in news reports and features. We visited the Slocum Massacre historical marker on the July 29 anniversary of the atrocity every year, one or the other, or both, and usually with other members of the Hollie and Wilson families.

After the marker effort was approved, I think we both thought things would settle down, and we could focus more on other stuff, especially our families and lives. And we did. But the Slocum Massacre and its victims never went away. The specters of Hollie-Jawaid’s ancestors literally and figuratively never stopped haunting us.

In the intervening decade since my feature on the Slocum Massacre was published, we have corroborated on two screenplays based on the Slocum pogrom, and while both have been optioned, neither has been produced.

Every year or two, another journalist, filmmaker, playwright, or other kind of writer approaches us with ideas about a compelling filmic, streaming, stage, or radio production, but nothing ever comes of it. We have become cynical. We are exhausted.

But a positive note appeared near the end of 2022.

*****

On pg. 92 of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas, I mention that the remaining five defendants in Anderson County District Judge Benjamin Gardner’s initial, still unprosecuted indictments filed a writ of habeas corpus at the state court of criminal appeals in Travis County. It was, again, early May 1911, and they were still incarcerated and being held without bail. I suspect Gardner knew there was little hope of their being successfully prosecuted and meted out what legal complications he could in lieu of the justice he was doubtful that the victims of the Slocum Massacre would ever receive. He was obviously proven right. Jim Spurger, B.J. Jenkins, S.C. Jenkins, Curtis Spurger, and Isom Garner were each granted bail and, after posting it, walked away free men. They were never tried in a court of law and were never punished for their crimes.

They weren’t the only ones, of course, just the most inconvenienced. Judge Gardner did what he could while he could, but dozens of the perpetrators of the Slocum Massacre were never arrested or charged, and dozens if not hundreds of the victims lost their lives and their property.

My father, E.R. Bills Sr., died while I was finishing my book on the Slocum Massacre, and I dedicated the book to him. On Nov. 10, 2022 — a day that would have marked my father’s 80th birthday — I received an email from Dr. Steven A. Reich of James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I learned that my research on the Slocum Massacre had been incomplete. I’d dug around in the Anderson and Houston county courthouse archives and found notes and basic proceedings on the cases against a few of the white folks behind the Slocum Massacre, but I’d never come across much actual testimony. And I — in my haste or inexperience — had missed the State Court of Criminal Appeals records at the Texas State Library and Archive Commission. Reich found them and reached out to me.

My research has unearthed records from the criminal proceedings, including the full transcript of the March, 1911, bail hearing that lasted 10 days. The more than 350 pages of sworn testimony from 54 witnesses, Black and white, offers a window onto the Black community, the massacre, its perpetrators, and its victims. It allows us to reconstruct the massacre –– at least the killing of six of the known victims –– with considerable precision. Even if the white people of Anderson County kept the crimes of their forefathers quiet for more than 100 years, their ancestors spoke on record about what happened. And their words have remained preserved in those court papers. Furthermore, the Black witnesses offer compelling testimony, on public record, about what happened to them and who pulled the triggers that killed their family members. The document reveals a remarkable effort by Black teenagers, women, and men to act politically with incredible courage to compel civil authorities to acknowledge and denounce the violence that visited their community.

I was dumbstruck at first and then mightily frustrated. I’d missed something, something that would have been incredibly useful in the skirmishes that Constance Hollie-Jawaid and I had with the Anderson County Historical Commission and others.

I had to see the record for myself. Reich had sent me excerpts and gave me a few clues but not the entire document. I located it immediately and ordered my own copy. Some of the surviving Black victims actually testified against the white defendants before a judge, even pointing out and identifying them at the time. And the defense team’s witnesses practically made the prosecution’s case for them. Here are some excerpts of from some of the damning testimony:

“I heard about the burning of that negro in Cherokee County, and I noticed the change in the negroes at that time. It seemed like to me it made the negroes worse; insolent and mean and impudent; more impudent than they had ever been before.”

“The negroes didn’t seem to be as quiet as they had been, and it seemed like they carried their guns more frequently.”

“They were bigoted and sassy among some white people.”

“And I noticed about their conduct after the Jack Johnson fight, and they would call each other Jack Johnson and say ‘well, you know, a negro is stouter than anybody else, and is more of a man.’”

“I met several of them in the road and they didn’t speak to me, and I didn’t think they acted very polite. I have seen them pass by whistling and talking and going on just like they didn’t care. That is what I call a bigoted person.”

“I remember the trouble they had down there near Slocum when the darkies were killed. I think the first darkies was killed on Friday; that is what I heard, but I don’t know only from what I heard … that the negroes were up to some devilment.”

“The negroes down there are not disbehaving now.”

After reading the entire 350-page transcript, I realized what I’d missed.

A football metaphor. A game changer.

For my book, I had relied on newspaper reports and second-hand accounts. The record of these Black and white eyewitness accounts dispels the need for speculation and theory.

Certainly, bad news for chronic sufferers of white fragility and white denial in Anderson County and across the state but also bleak for conservative politicians, the regressive Texas legislature, and the delusional critics of Critical Race Theory.

In the next year or two, Reich will no doubt complete an invaluable examination of the economic disenfranchisement of Black citizens in Anderson County, Houston County, and probably across Texas. And by the time you read these words, Hollie-Jawaid will already be working on releasing an annotated version of the eyewitness testimony for your perusal (probably on the 2023 anniversary of the atrocity).

So, Chiefs, Eagles, Cowboys, Texans, NFL fans in general, you will soon become the final arbiters of what needs to be done. You will decide who was exaggerating and who was telling the truth. You will be tasked with delivering the justice the Slocum Massacre victims have so long been denied. And you’ll receive a crash course on why white conservative politicians in Texas are so leery of the truth and of admitting that they openly limit the voting rights of persons of color and still abridge their legal rights and economic opportunities every way they can.

Then, in the next decade or so, not just a historical marker but a full-blown state-funded monument — not unlike those standing to commemorate the victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre in Oklahoma, the Rosewood Massacre in Florida, or the Elaine Massacre in Arkansas — will be standing in East Texas.

It will be bigger than a Super Bowl, and it’s somewhat ironic.

The rights and privileges that so many Texans have been complaining about losing the last several years are the same rights and privileges white conservatives were allowed to kill Black people for seeking or simply enjoying in 1910. My original Statesman article on the Slocum Massacre was an earnest but clumsy start, but these eyewitness court documents will serve as indisputable proof.

I have your book. keep up the great work.