Lupe asked me to meet her early at Tarrant County Jail. Her incarcerated boyfriend is allowed only two visitors a day, she said, so arriving in the morning ensured we were allowed in. After we showed our IDs to a sheriff’s deputy, we took the elevator to the seventh floor and waited for the inmate to arrive. Lupe asked to conceal her last name to protect her privacy.

At the end of the hall sat four partitioned booths. Bits of litter were scattered along the decrepit floor, and a palpable smell of urine filled the air. Lupe said she has known her boyfriend for around 20 years. She met him when he was a “punk-ass kid,” she said with a laugh.

“He really was just a kid,” she continued. “He was just over 20 at the time.”

The two remained friends for most of those two decades, only dating the past few years. After Fort Worth police arrested him in early October, Manual Mata collect calls her up to three times a day, she said.

When the thin 42-year-old with closely cropped black hair found our booth, his face and ours separated by thick glass, he smiled.

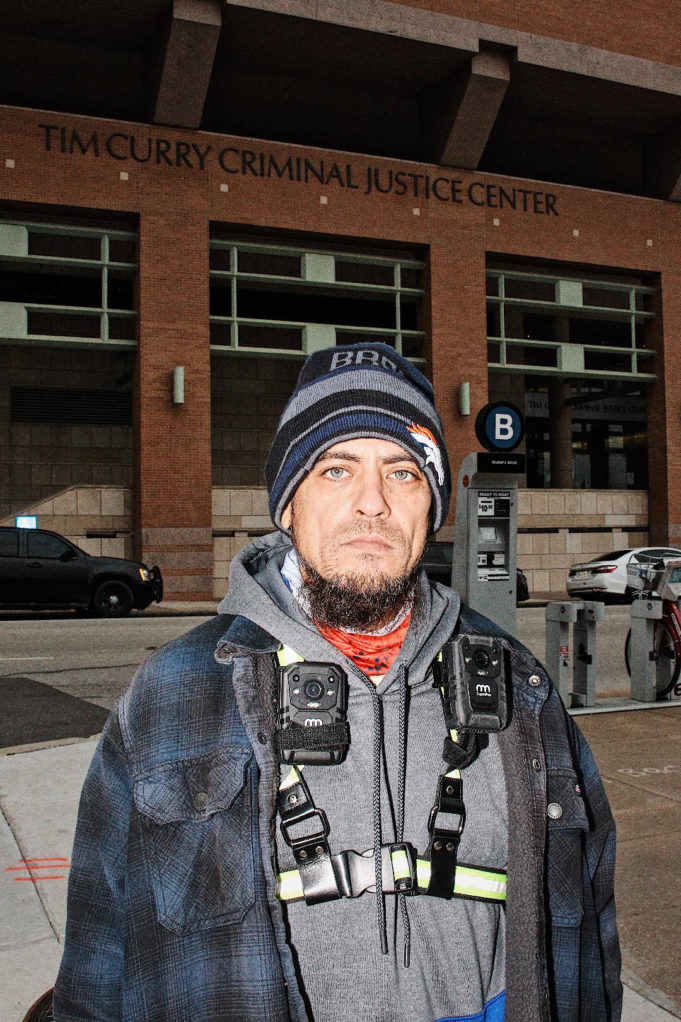

Over the past two years and through his YouTube channel @ManuelMata, the self-described citizen journalist has broken stories on employees at the Tarrant Regional Water District calling 911 on visitors livestreaming board meetings, even though such practices are perfectly legal, and one year ago, he posted a video of receiving a trespass warning from a Fort Worth police officer while attempting to enter a police station to file a complaint. Though never trained as a journalist, Mata has a firm grasp on Southside policing practices, and he has good instincts and a strong work ethic.

The week after my jail visit, I received a call from Lupe’s number. It was Mata. Earlier that day, he had had his $18,500 bail paid by a fellow citizen journalist. Mata told me he planned to “lay low” for the near future and focus on having his several misdemeanor charges dismissed.

Mata livestreamed the events that led to his October arrest. The police interaction has tallied more than 5,000 views on YouTube. In the video — titled “Fuck You Dirty Cop” — Mata walks along a sidewalk on the South Side as two Fort Worth police SUVs are visible in the distance. Officer Doug Bengal exits one of the vehicles and rushes toward Mata, ordering him to turn around walk away from the SUVs.

Mata replies that no law restricts civilians to so-called reasonable spaces.

“I can walk down the sidewalks,” Mata shouts back at Bengal. “Is it true or not?”

Bengal walks away before abruptly turning around and telling Mata that he is resisting arrest. The police officer handcuffs him.

“What you’re doing is illegal,” Mata tells Bengal. “Official oppression. Untruthfulness. I know the law better than you do.”

Mata told me Fort Worth police are doing everything they can to keep him in jail so he cannot livestream more police encounters.

“I was walking back to see my girlfriend,” Mata said, referring to his unintended run-in with Bengal.

Courtesy YouTube

In many ways, Mata is a surrogate for founded or unfounded outrage by left- and right-wing groups against the status quo. Figures who have voiced support for Mata include C.J. Grisham, a former Army sergeant who, when running for an open state rep position in 2018, said the FBI agents who fatally shot antigovernment militiaman Robert LaVoy Finicum should be “lined up and shot.” Mata’s courting of Grisham recently led several progressive-minded locals to distance themselves from him.

Still, the citizen journalist’s vocal criticism of county leadership has made him popular on social media with his followers of the broader citizen auditor movement that relies on volunteers who audit government business, usually through photographing or filming public spaces. The idea is to assert freedoms like the right to film police officers as a means of keeping government transparent and accountable.

*****

I first connected with Mata in late 2021 via emails and phone calls. He wanted to alert me to police misconduct on the Near Southside and around nearby Hemphill Street. On several occasions, Mata told me that the Fort Worth Weekly was the only publication in town to report on official corruption and law enforcement misconduct. Mata told me about his past. He was two years out of prison at the time, following an eight-year stint for felony drug possession.

Throughout his incarceration, Mata said he avoided gang affiliations.

“I’m no gang member,” he told me. “I went through hell staying out of gangs. Gang members killed my little sister in 1999. I would never be in any gang.”

Her name was Mary, and she had just turned 16. Anyone who knows Mata understands the drive-by shooting is something he relives frequently. The anger he feels toward his sister’s murderers drives his disdain for injustice in all its forms. For backers of the blue, tying law enforcement to criminal conduct might seem peculiar at best, but Mata told me that in many poor Hispanic neighborhoods, the residents view the police as criminals.

“I’m Mexican,” Mata said during one of our early interviews. “I live in a poor neighborhood. To police, I don’t fucking matter. We don’t have a BLM for Hispanics, Chicanos, and Latinos. The police throw it in my face. ‘You are not going to matter because of your race and where you live,’ they say. They tell me this shit, but they turn off their cameras.”

After seeing police allegedly mute or turn off their cameras when it suited them, Mata realized that he needed to livestream his encounters with law enforcement, for his own protection and as evidence of misconduct. In mid-2021, Mata discovered the Dell Dehay Law Library. He spent six months visiting the downtown library to research the rules and laws that govern policing in Texas.

The cops “have a policy and procedure to follow,” he told me. “If they don’t, they lose their job. Their job isn’t to protect officers’ mistakes, and that’s what I’m going to teach them. They think I’m dumb because I’m a Mexican and where I live. I’m tired of it.”

Courtesy YouTube

Peruse Mata’s YouTube channel and his evolution as a self-described citizen journalist is apparent.

Mata’s channel has several thousand followers. The bulk of his livestream videos in 2021 and early 2022 focused on Fort Worth police. Five months ago, the scope of his work began to broaden, thanks to his friendship with Thomas Torlincasi.

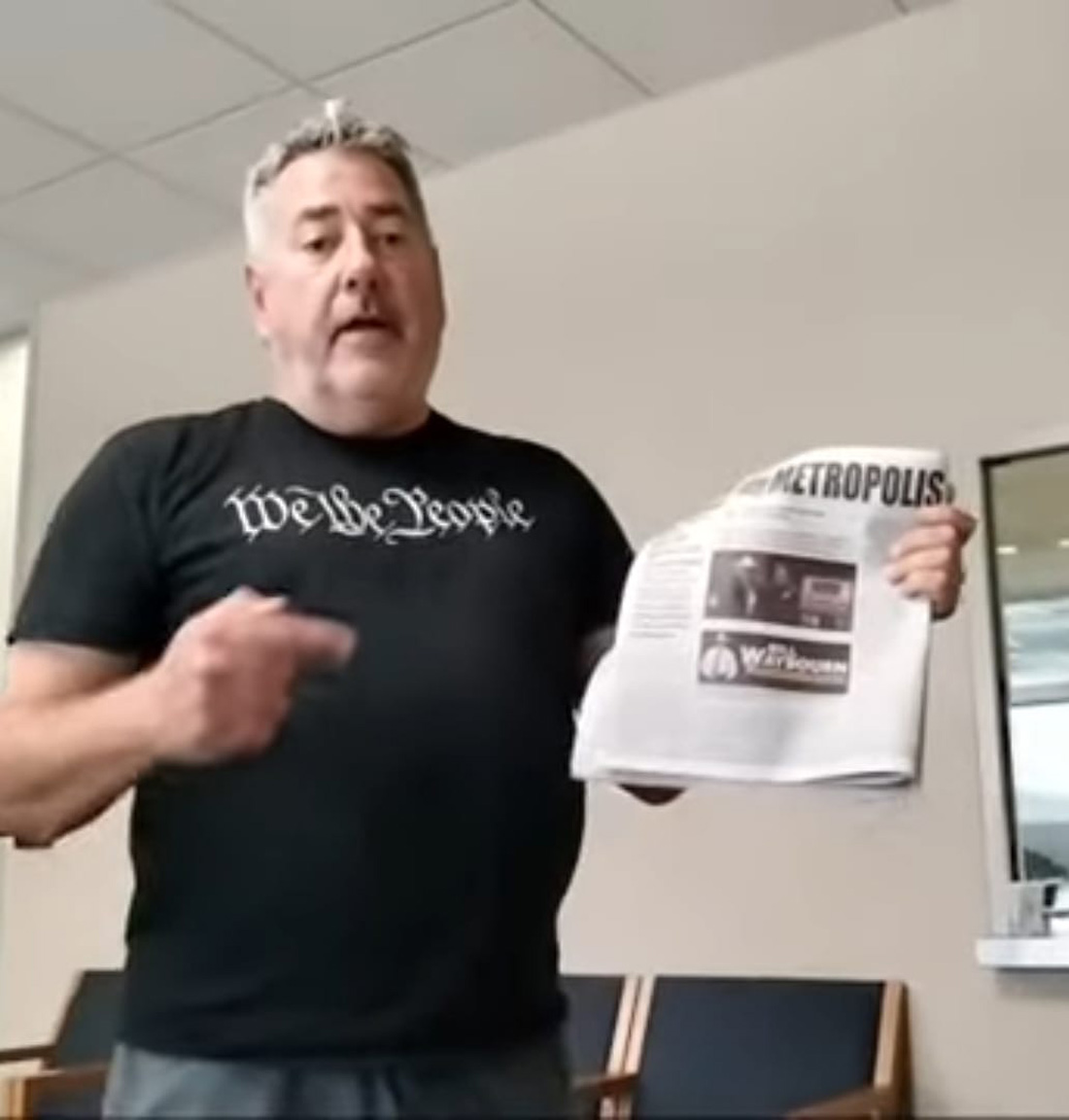

Torlincasi could be the subject of his own cover story, and he would deserve the recognition. The Fort Worthian who recently died of a heart attack at 62 pushed Mata to sleuth for corruption, not on the streets of the South Side but in government buildings where officials were used to conducting business largely outside the public eye.

Outwardly, the two couldn’t appear more different. Heavily tatted and usually sporting a baseball cap, Mata looked the part of a former felon to many outsiders. Torlincasi, middle-aged and white, was a polished public speaker. The two found a common interest in attending meetings of Tarrant County’s commissioners court and Fort Worth City Council, usually with Torlincasi speaking and Mata filming.

When security tried to prohibit either of them from speaking or filming, Mata would use the confrontations to further his case by quoting relevant laws or case law. He occasionally edited the videos to add commentary or literally superimpose clown faces over elected officials. In private conversations, local supporters of government accountability told me they lauded the sometimes outlandish acts while others thought it was mere spectacle and possibly counterproductive to reform efforts.

Mata said he misses his friend Torlincasi.

“This would be a lot easier if he were still here,” Mata continued. “It’s like having a good lawyer. That’s what Thomas was for me. No matter what I was doing, he reassured me that was what we needed to be done. They have been able to silence and threaten people forever here in Fort Worth.”

Torlincasi, he said, spoke on behalf of people who felt intimidated.

Courtesy YouTube

Mata and Torlincasi shared an affinity for confrontation. The brazen games of brinksmanship with police and sheriff’s deputies occasionally landed Mata in jail. One of his remaining misdemeanor charges is for allegedly assaulting a peace officer at the northeast headquarters of the Tarrant Appraisal District (TAD) in mid-August. As Mata was preparing to livestream a TAD board meeting, several sheriff’s deputies who work security at TAD confronted Mata and Torlincasi.

The incident was livestreamed on Facebook.

Based on the recording, Mata and Torlincasi are waiting near an area that TAD had cordoned off for media. As Thomas steps outside the area to interview some board members, TAD communications officer Ricardo Aguilera approaches him. Aguilera then tells Torlincasi that he had been warned not to leave the cordoned-off section before approaching sheriff’s deputy J.D. Thomas, who has a history of making false arrests (“ Damage Control,” Aug. 31). Soon after, several sheriff’s deputies begin pushing Mata and Torlincasi out of the room.

“They wouldn’t let my arms go,” Mata recalled. “I told them that my arms hurt. They were trying to be friendly to me at first. I asked them to let me go, so I could walk out.”

After Mata’s arrest, Torlincasi took to Facebook to post about his brother-in-arms.

“Manuel Mata remains a political prisoner in Tarrant County Jail,” Torlincasi wrote. “Keep in mind, Manuel has been convicted of zero of the crimes they charged him with. Every single one is a charge based on his exerting his civil rights.”

*****

Speaking to the commissioners court in late September, retired librarian LaVonne Cockerell described alleged police surveillance of Mata’s home in the Hemphill neighborhood.

“After the death of Thomas Torlincasi, I and a large group of people have taken up his concerns, and his most pressing concern is the safety of Manuel Mata,” Cockerell said. “Mr. Mata lives six blocks away from my house.”

After dropping off Mata downtown on a parole-related visit, Cockerell recalled a truck coming around the corner of their street.

“Out of the sunroof, a woman with a tatted hand and blonde hair took a cell phone picture, which was a little disconcerting. I got her tag number. That truck was seen later in the neighborhood with different tags. That worries me because [Torlincasi] felt like [Mata] was being targeted.”

Cockerell told the commissioners that she does not want a stress heart attack, a reference to one possible cause of Torlincasi’s death.

“I would like to talk to this woman,” Cockerell continued, referring to the blonde in the truck. “I would like to know if she is connected to the sheriff’s department or anyone with the police.”

Mata and his supporters maintain he lives under a constant state of police surveillance. Cockerell told me that, at one recent meeting at Ol’ South Pancake House where several of Mata’s supporters gathered to discuss ways to address his misdemeanor charges, a large sheriff’s department transport vehicle pulled up. Cockerell spoke to a restaurant employee who said the deputies chose the spot because they knew Mata’s friends were there.

While chatting with Mata in late September near his home, I noticed a constant stream of Fort Worth police cruisers pass his home. West Richmond Avenue, Mata said, is not a busy or important thoroughfare, yet police constantly patrol the neighborhood.

Shortly before Torlincasi died, he told me the police aren’t the only ones targeting Mata. Magistrate Judge Melinda Lehmann, he alleged, oversees magistration — a step that sets bond conditions — of cop watchers. If the powers-that-be wanted to keep citizen auditors detained indefinitely, that decision would come from a magistrate judge in possible consultation with the district attorney’s office.

I requested copies of communications between Lehmann and assistant district attorney Ashton Moore, who is assigned to Mata’s case. The administrator for Tarrant County’s magistrate judges refused to give me copies of the communications, and judges at the state Office of Court Administration ruled that Tarrant County magistrate judges could bar the release of the emails.

Tarrant County’s magistrate judges do step outside their job descriptions to selectively target individuals as favors to the powerful and well-connected. A Tarrant County jury recently found me not guilty of harassing the maternal grandfather of my daughter five years ago. The offense was around 15 unanswered phone calls over the course of a few weeks to him to let me know if my child was alive and well.

During my June 2019 arrest tied to those charges, I found myself in a small Tarrant County jail cell with a dozen other defendants awaiting magistration. Judge Mark Thielman arraigned me last after the room was empty, save for two sheriff’s deputies.

He told me he is “friends” with the alleged victim.

I took his actions as an overt act of aggression and intimidation. I later learned via Rule 12 requests that Thielman was communicating with other magistrate judges, including Tamla Ray, to inform them that he knew the alleged victim. Thielman meddled in my child custody case by placing my daughter on a no-contact order. He also required that I install spyware on my phone and computer that allowed DA Sharen Wilson’s administration to monitor the activities of one of the most published reporters in Tarrant County.

It took intervention by my attorney Terri Moore to remove my daughter from Thielman’s no-contact list, which allowed me to meet my 4-year-old daughter only two years ago.

Mata put it simply.

“They will come after your family,” he told me, referring to the criminal justice system’s willingness to target perceived foes, whether citizen auditors or professional journalists.

“These people use three ways to fight people who are effective in exposing” public corruption, he continued. “They will come after you criminally, they will take your kids, or they will try to prove that you are crazy. They will have a cop take you to John Peter Smith Hospital or find another family member to say [you are crazy]. They will criminalize parents for exposing a bad judge or lawyer. That’s how they will attack you.”

*****

“Did you read the 97-page report?” Mata asked me in October, referring to the comprehensive document that Fort Worth officials commissioned after police fatally shot Atatiana Jefferson in her home in 2019. A panel of police reform experts spent more than two years speaking to locals and examining policing practices in Fort Worth. The findings were damning.

Police interactions with people of color, the report found, are very different from policing in whiter, wealthier neighborhoods.

“Daily encounters [in poor communities] are far too often characterized by a command and control approach to policing that leads to avoidable uses of force and creates tension with residents who encounter police officers,” the report reads. “The failure to use effective de-escalation techniques continues to be a significant issue that has increased mistrust. Accountability for aggressive police tactics is frequently anemic or ineffective, missing both individual and systemic problems. Compounding the issue, the panel heard reports from supervisors in the [police] department that middle managers were discouraged from raising issues unless there had been a complaint or a public outcry.”

In the report, the authors pinpoint systemic problems like overreliance on SWAT teams and no-knock warrants, inadequate responses to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis, and a general lack of relationship-building between police patrols and the communities they serve. Mata sees a direct line between his livestreamed interactions with law enforcement and the report’s findings.

“These are the same things Thomas Torlincasi and I have been saying,” Mata continued. “When it comes from us, they dismiss what we are saying. When it comes from a police panel, they take it seriously.”

During the September presentation of the experts’ findings, Fort Worth City Council, city staffers, and Police Chief Neil Noakes discussed the findings in depth. Expert panel lead Alex del Carmen concurred and said that data doesn’t lie.

Toward the end of the two-hour presentation, Noakes told city councilmembers that his officers have a duty to intervene if they witness police misconduct on the part of their peers.

“If they don’t intervene, is there a consequence?” asked Councilmember Chris Nettles.

Yes, sir, the police chief responded.

In the report, the authors name several areas where policing practices are improving. The police department’s Crisis Intervention Team, which is tasked with addressing mental health-related calls, has expanded from six to 20 officers. Reliance on SWAT teams has dropped considerably over the past few years, and training methods for recruits are now less militaristic.

Efforts to add civilian oversight to Fort Worth’s police department recently stalled. The proposed nine-member board would have reviewed police practices and recommended changes, based on the ordinance partly drafted by Fort Worth’s Police Oversight Monitor, who has been performing similar work for two years. Mayor Mattie Parker, who maintains strong support from the local police union, voted against the oversight measure in the 5-4 decision. Councilmember Elizabeth Beck was the only non-Black councilmember to vote for the oversight board.

Here and across the country, law enforcement talking points against independent oversight usually emphasize how civilians can’t comprehend what cops go through on a daily basis. It’s an argument that won over our mayor and most of City Council, but Mata thinks it’s stupid.

“We didn’t ask that cop to apply for that job,” Mata said. “What we [in the community] did ask was to be treated with respect, equality, and dignity [by cops]. That’s what we did ask for.”

The only solution to police misconduct and brutality is to lock up offending officers, he said.

“Instead of correcting cops, these supervisors are condoning this type of behavior, so the officers think it’s OK to do this,” Mata continued. Misconduct on a local level happens “two, three times a day. That day turns into a week. That week turns into a month. Now that month has turned into a year. For a whole year, that officer was shown a shitty practice that does not coincide with [the department’s] policies and procedures.”

Judges, prosecutors, and district attorneys cannot be trusted to push back on police misconduct, he said. Doing so would slow the steady stream of locals caught up in the criminal justice system that leads to around 45,000 criminal cases per year in Tarrant County alone.

A handful of citizen auditors cannot begin to diminish the damage corrupt leadership at the DA’s office, commissioners court, and sheriff’s department can inflict on the civil rights of locals, Mata said. All leaders like county judge-elect Tim O’Hare and Sheriff Bill Waybourn have to do is target and arrest perceived threats.

“These problems are going to carry over to the middle class and the rich people,” Mata said. “Eventually, [corrupt cops] will fuck with those people, too. If you are criminalizing one part of the community, you are creating a culture where cops know they are protected. They will carry on into these middle-class neighborhoods. I don’t want it to get to that point. I want the rich and middle-class people to understand that poor people need their help. [Those with influence] are the ones who give cops power by their money, votes, and influence.”