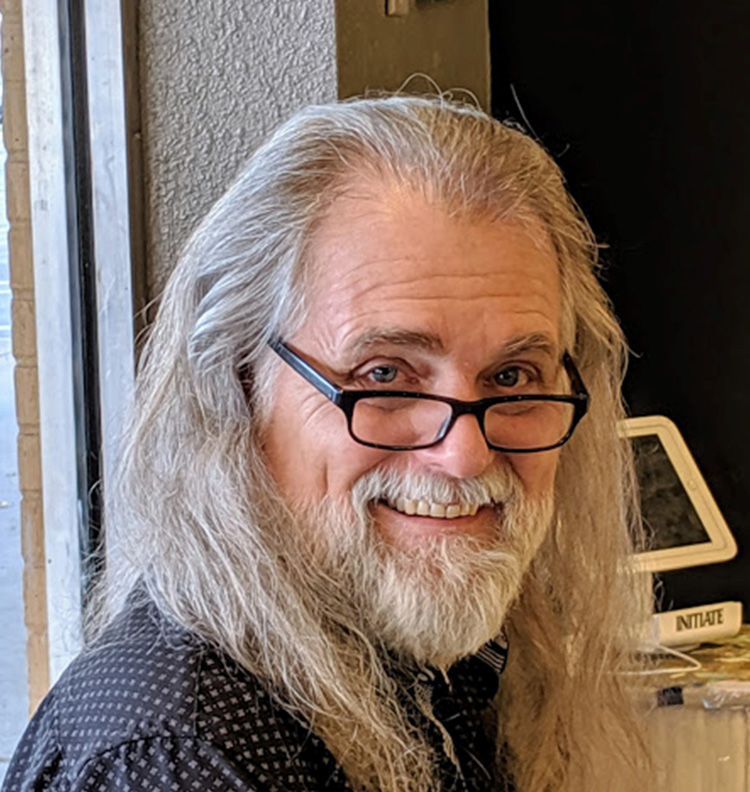

People who work day-to-day, blue-collar, service jobs intersect most of our lives all the time, but we don’t give many if any of them a second thought. The pseudo-cheery teenager handing us our order at the drive-thru window. The bedraggled serviceperson who came out to replace the worn-out element in our water heater. The Big Lebowski-looking fella who painted all the exterior trim on our house for cheap. A delivery person for a chain sandwich shop, a waitperson, a landscaper, a maintenance employee, or a bartender. I’ve never confirmed the specifics precisely, but I know that at one time or another Fort Worth native Bret McCormick has been at least half of these folks, so you wouldn’t think he was a disfigured serial killer butchering our unsuspecting neighbors as a janitor at a Texas high school.

And he’s not.

He just plays one in his latest movie, Christmas Craft Fair Massacre.

It’s a wacky, no-budget horror film that will be available from Wild Eye Releasing on DVD and Tubi in mid-December. In fact, it’s so low-budget, it actually cost him more to rent the Bedford Movie Tavern for the premiere than it did to actually complete the production.

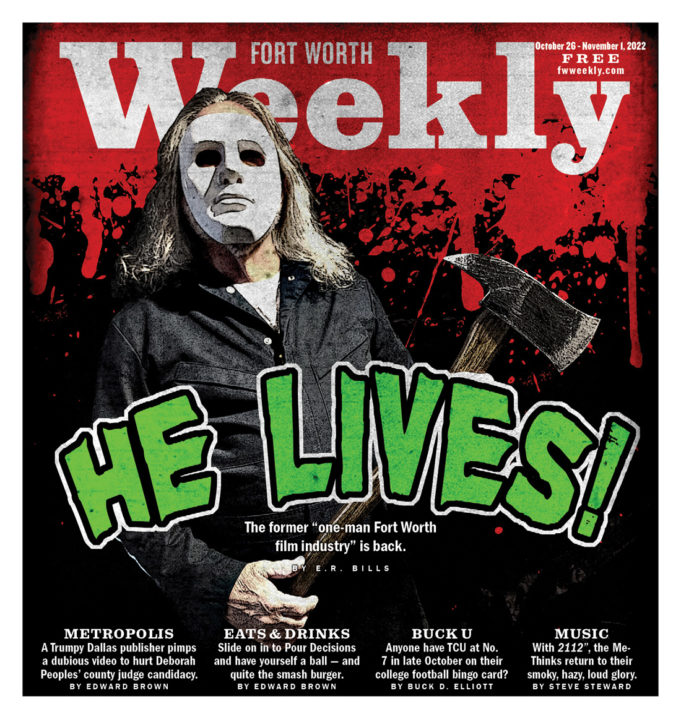

To be honest, it seems fitting in a way, for this previously, partially, and perhaps still part-time demented master of Texas schlock to reemerge from the shadows. A tall Timothy Leary-looking figure of no small renown, McCormick is not exactly a Cowtown knock-off of Ed Wood. He’s more of a Roger Corman disciple, and his body of work is characterized by madcap low-budget zaniness, often produced by sheer force of will alone, when so many others might have quit. At his best, he was half-Stanley Kubrick, half-Mel Brooks, a Frankenfilmmaker, a celluloid dervish of stoic edge with sometimes trashy, sometimes eruditely hashy, blunt humor. After all, most of us weren’t put on this planet to be a big noise or make a big splash. And even if we were, many of us were disinclined to perform the pandering required to put our names up in the big bright lights. McCormick would humbly admit to said ranks. They Live. We live. He lives!

Courtesy the artist

But here’s the difference.

Remember when you were a twentysomething sitting around on a crappy couch in a crappy apartment, watching a crappy direct-to-video monster muddle? You were momentarily inspired, and you thought, “Hell, I could do that!” And then, praise the Lord and pass the corndogs, you actually went out and did it?

Of course not.

You may have had the crappy couch in the crappy apartment and been susceptible to the almost obligatory viewing of crappy direct-to-video monster shows, because these are the easy half of the equation. Watching movies and laughing at their inadequacies requires no exertion, little time, and even less talent.

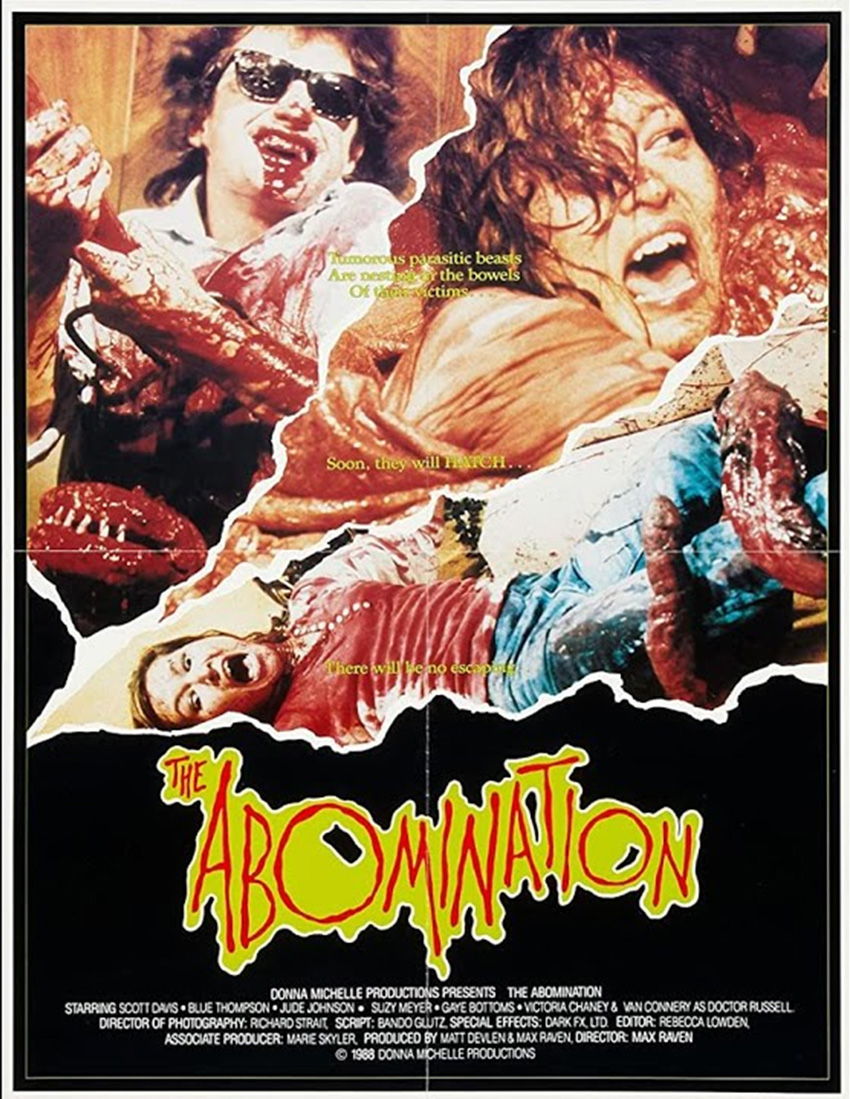

Some of us, however, have seen the 1986 schlock horror classic The Abomination. And the who is the why of the how.

*****

Otto is a directionless young punk whose parents watch religious TV all day and tell him they gave away his college money to help support a television evangelist doing the Lord’s work. Otto isn’t a character in The Abomination. Otto (played by Emilio Estevez) is the main character in the 1984 classic Repo Man, but what if the college money that Otto’s parents sent to that broadcast prophet had yielded a miracle in the clenched opposable-thumbless fingers of “The Monkey’s Paw”?

This — drumroll, please — is Bret McCormick’s territory.

There were more than a few directionless young punks in rural Texas in those days, so McCormick introduces us to Cody (Scott Davis), who is aimlessly adrift, perhaps, but handsome in a redneck, quasi-mulleted sense and even possessed (initially) of a girlfriend. Cody, like Otto, competes with a televangelist for the attention of his mother Sarah, but she is obsessed with binge-watching the technicolor savior Brother Fogg to secure spiritual deliverance. She has a terrible cough, suspects a tumor, and wonders why her son Cody rejects the TV preacher’s delusional aplomb.

Courtesy the artist

Ariel hangs out with her crazy redneck friends, pulling dumb stunts like doing the splits between two trucks racing down a country road, her feet precariously balanced on the open-window doors of the two vehicles. But as played by Lori Singer, Ariel isn’t a character in The Abomination. McCormick’s budget for The Abomination was 1/1,170th that of the cheesy 1984 classic Footloose ($8.2 million), which starred Singer and, as Ren McCormack, Kevin Bacon.

So, what’s an aspiring filmmaker who sprang from a crappy couch in a crappy apartment to do?

It’s simple, really. And more realistic. Cody and girlfriend Kelly (Blue Thompson) race their friends down a country road, driving close enough to pass beers back and forth between their truck cabs. It’s certainly more realistic than Singer’s Footloose stunt and practically a rite of passage in Texas anyway.

Meanwhile, Sarah’s cough worsens, and she desperately prays to Brother Fogg for a remedy, divine intervention, and salvation. And that’s where the weird salivating begins. Cody’s mother coughs up a bloody lung tumor and, feeling better, tosses it in the trashcan. Then, she goes to bed and sleeps the sleep of the damned — sorry, I meant “dim.”

After a day of provincially rambunctious country road beer-swapping, Cody comes home loaded and passes out. The heaven-cast-out (or hell-cast-forth) bloody lung tumor begins to pulsate. If this sounds wacky or far-fetched, remember the parallel points in Repo Man and Footloose. Otto is fetching cars and chasing a space alien stashed in the trunk of a missing 1964 Chevy Malibu. And Ren and the quite fetching Ariel are — as Peter “Starlord” Quill in Guardians of the Galaxy so eloquently puts it — challenging a towering prig (played by John Lithgow) to a “dance-off.”

This is where McCormick really demonstrates his knowledge of the material and his meager budget. The bloody, burgeoning, heaven-sprung lung tumor can’t hide in cars (yet), and a dance-off is out of the question. So, the bloody, pulsating tumor hits the linoleum and oozes its way to comatose Cody’s bedroom.

Courtesy the artist

Here, instead of discussing how said pulsating, bloody lung tumor scales Cody’s bed, we must examine the influence of Frankenstein. Victor Frankenstein’s goal is to use science to stave off death, an arguably noble intention, but his efforts backfire. He creates a monster. Defying science, Cody’s mother attempts to prolong her demise by praying to and paying Brother Fogg, clearly an ambassador of the Lord. She implores Fogg for a miracle cure and receives one. It’s alive! But unlike Mary Shelley’s monster, it doesn’t flee from human beings — it wants to devour them. It’s way more bent on world domination than the Evil Plankton in SpongeBob SquarePants and arguably as gross and otherworldly as the creature in John Carpenter’s 1982 version of The Thing (whose production and special effects costs were a thousand times higher).

The throbbing, bloody lung blessing is actually a curse, and it crawls into the sleeping Cody’s mouth, where it plants its seeds. Later, Cody regurgitates the tumor, or one of its brothers, and tucks it under his bed, where it grows into a voracious eating machine, eager to be fed.

Here, we must comment on McCormick’s Alien turn. Ridley Scott also has his extraterrestrial creature impregnate a male character orally, but that fecundated male’s pregnancy results in a nasty newborn-performed Caesarean. As The Abomination’s budget was 1/13,956th of Alien’s ($11 million), McCormick remains frugally faithful to The Abomination’s theme of oral deliverance. Cody repeats his mother’s regurgitative labor, producing another living, bloody offspring from his kisser.

Cody soon begats another tumorous offspring, and, in a matter of days, the growing clan of tumors are hangry.

In Repo Man, Otto never repossesses the 1964 Chevy Malibu and misses out on the alien in tow. Cody gets possessed by his mom’s bloody, coughed-up tumor and feeds his growing litter of abominations any humans he can manage to kill: friends, strangers, his boss, and the tumor’s original progenitor, his own dear mother. In Footloose, Ren and Ariel win their dance-off against the local preacher, but McCormick does them one better. Cody places one of his offspring in the toilet of the sinister televangelist. Unfortunately for Brother Fogg, the aperture of a toilet bowl is much wider than the eye of a needle.

In bizarre, lean ways, The Abomination is cleverer and more pointed than Repo Man, and some of its $2.68 special effects may be better (though created in the same playful vein). The shoestring-budgeted indie is also more relevant than Footloose, whose small-town characters seem based on rural Texans. In fact, to be snidely candid, The Abomination doesn’t borrow from Footloose so much as perform a twisted, irreverent response to it.

Can’t say too much more without giving up the entire plot, but the film was shot mostly in Poolville, Texas, in 10 days in September 1986. Bret McCormick did the most with what he had and accomplished what many of us thought we could do sitting around on a crappy couch in a crappy apartment if we just got the chance.

Clearly, McCormick didn’t wait for chance.

In 1983, a screenplay McCormick wrote with Lon Bixby was optioned by Hollywood legend Peter Fonda for $1. Paltry, yes, but it still gave McCormick showbiz cred.

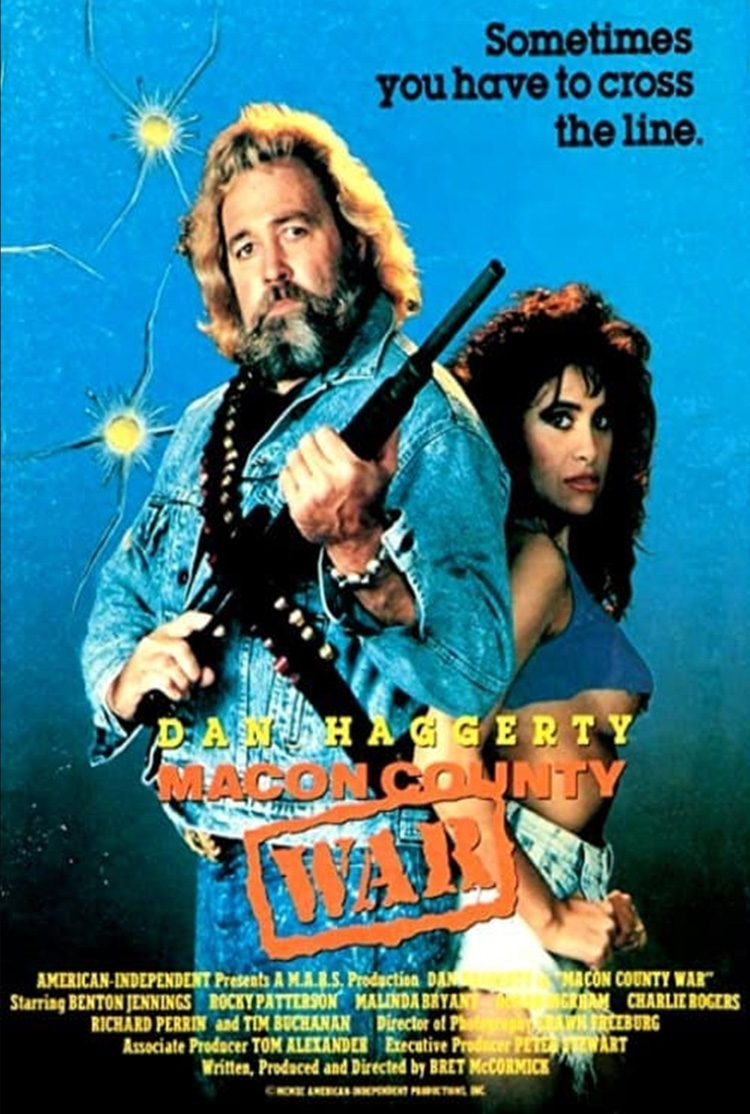

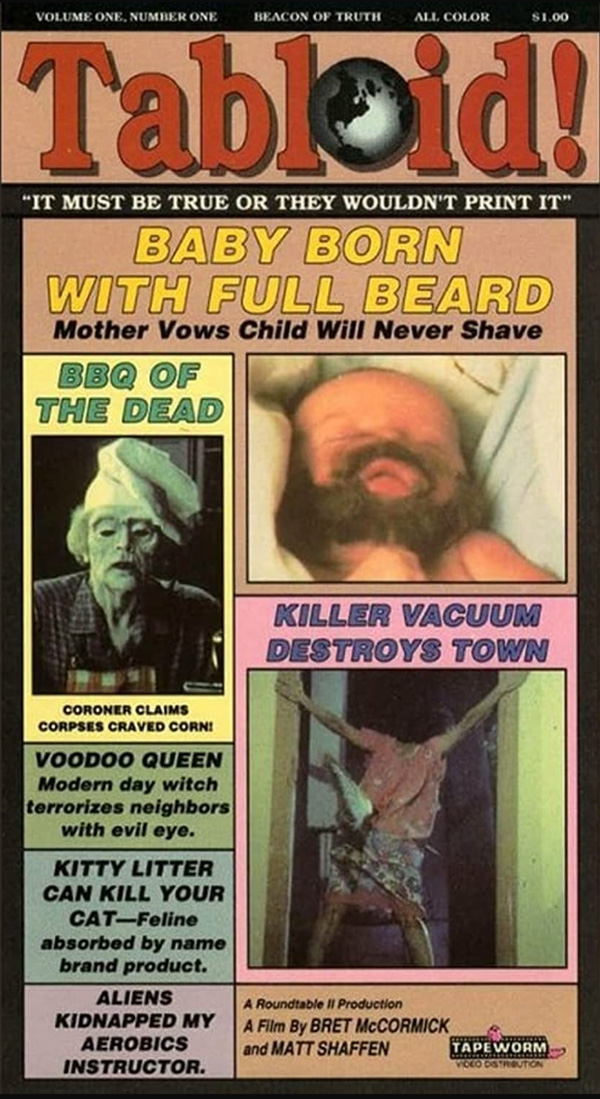

Then, from 1985 to 1998, the budding filmmaker produced more than 20 low-budget features, including Tabloid (1985, a collection of shorts that includes McCormick’s clever “Barbecue of the Dead”), the afore-discussed Abomination (1986), Ozone: Attack of the Redneck Mutants (1986), Macon County War (1990, a.k.a. One Man War and starring unruly, coked-up Grizzly Adams star Dan Haggerty), Highway to Hell (1990, starring screen legend Richard Harrison, who appeared in more than 100 motion pictures from 1955 to 2000), Armed for Action (1990, starring Martin Sheen’s younger brother, Joe Estevez, uncle to Repo Man star Emilio), and Blood on the Badge (1992, also featuring Joe Estevez). In 1992, McCormick also produced both Redneck County Fever and Reanimator Academy (which included a small role for Sarah Paxton, who would go on to appear in Last House on the Left in 2009 and the 2022 Marylin Monroe biopic Blonde) after one-weekend shoots. He was also an associate producer on Night Trap (1993, starring future Hollywood mainstays like John Amos, Robert Davi, Lesley Ann-Down, Michael Ironside, and Mike Starr), and then he produced the 1994 documentary Children of Dracula (a fang-in-cheek nod to a genre that would eventually evolve into comedy-reality features like What We Do in the Shadows two decades later). McCormick would also go on to write the screenplay for Fatal Justice (also starring Joe Estevez) that year.

Courtesy the artist

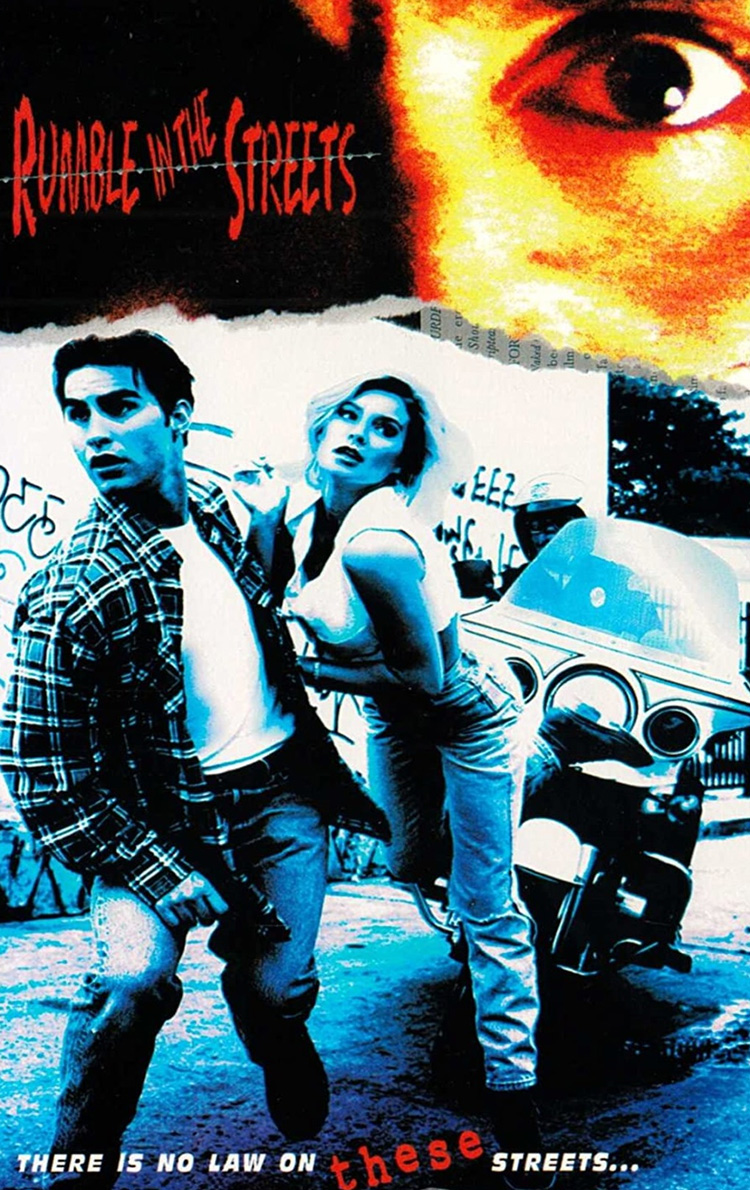

From there, McCormick produced Cyberstalker (1995, starring former Re-animator star Jeffrey Combs), Striking Point (1995, starring Robert Mitchum’s second son, Christopher Mitchum, who appeared in more than 60 films, including three with John Wayne), Space Varmints (1995), Takedown (1995, starring Richard Lynch, a stalwart Hollywood villain of The Sword and the Sorcerer fame), Bio-Tech Warrior (1996), Rumble in the Streets (1997), Time Trap (1997, starring Jeffrey Combs), and the inimitable Repligator (1998, starring Gunnar Hanson).

In the 1995 book Sleaze Merchants: Adventures in Exploitation Filmmaking, author John McCarty calls Tabloid “a cross between The Rocky Horror Picture Show and the perverse early works of John Waters.” Pop-art icon Andy Warhol even gave it an endorsement, describing it as a contemporary Norman Rockwellian vision of “Americana.”

The Confluence of Cult website calls McCormick’s “visceral Super 8 indie” The Abomination a “messy tangle of glorious splatter and existential absurdity” that stands out as a “worthwhile curio, a sort of 8-track [David] Cronenberg demo.” And the subsequent, non-McCormick-produced 1992 version of Highway to Hell — starring Rob Lowe’s younger brother Chad Lowe, Ben Stiller, Jerry Stiller, Patrick Bergen, Kristy Swanson, and rockstar Lita Ford — was produced for a budget of $7.5 million and grossed only $26,055 at the box office. Juxtapose that data with the fact that McCormick put together the 1990 version for $20,000 and recouped his budget and then some.

Night Trap earned McCormick his first Joe Bob Briggs review and rating: “Nine dead bodies. Twelve breasts. Blood-drinking. Wrist-slitting. Two bodies flung through plate-glass windows. Hooker torture. Exploding house. Four motor vehicle chases, with four crashes, explosion and fireball. Drive-In Academy Award nominations for Michael Ironside, as the you-know-who, for saying, ‘Whose body would you like to hold next to you in bed while the other lies rotting in a grave?’ Two and a half stars. Joe Bob says check it out.”

Rumble in the Streets, which McCormick produced for horror legend Roger Corman, received a second, particularly expository Joe Bob write up:

Bret has always been the one-man Fort Worth film industry, but I remember the ole boy when he was making monster flicks for 30 bucks in his cellar.

Seven dead bodies. Six breasts. Face-clawing. Dirt clod to the eyes. Bloody scotch-glass crunching. Hand-slicing. Hand-burning. Hand-crushing. Close-up heroin injections. Guy executed by gunshot in a place where … naw, we’re just not going into it.

Leg-stabbing. Flaming cop. One motor vehicle chase, with crash. One mugging. Aardvarking. Electrocution.

Drive-In Academy Award nominations for Peggy Ann Mitchell, for writing and singing the main theme song, “She Tries to Fly,” a great song in a genre that usually thrives on bad songs.

Kimberly Rowe, as the hooker who says, “I keep thinking I know you from somewhere — I always remember guys on bikes,” and, “I don’t do that much heroin — just enough to stay straight.”

Mike Nicole, as the scruffy, wisecracking drug connection who says, “My name’s Bob, but I spell it backwards.”

David Courtemarche, as the lovestruck, homeless singing cowboy.

Patrick Defazio, as the sick, perverted, twisted street cop.

And Bret McCormick, the director, co-writer, and producer, for doing things the drive-in way,

Three and a half stars.

Joe Bob says check it out.

In a review of Time Trap, The Terror from Beyond the Daves website claims, “The best way I can describe Time Trap is Star Trek meets Land of The Lost” and rates it “7/10 stun blasters!!”

And Repligator, ranked the 1,096th best film of 1998, received the following review from Triskaidekafiles: “Things could stand to get a little cheesier, but I love the ludicrousness of every damned thing in this movie. It’s like watching a terrible Doctor Who story from the classic series but with more boobs. I’d almost say watch this just for the entertainment value alone, because, damn, if it isn’t something unique.”

A nod from Andy Warhol? Comparisons to John Waters, David Cronenberg, Star Trek, Land of the Lost, and Dr. Who? And a fricking Academy Award nomination from Joe Bob Briggs, the all-time, undisputed master of B-movie horror pictures?

Who is this masked, creeping cinephile, and what happened to him?

*****

As McCormick notes in his recent book, Texas Schlock: B-Movie Sci-Fi and Horror from the Lone Star State, he became obsessed with Edgar Allan Poe when he was not much more than a toddler and fell straight into the suspenseful, buttery-popcorn embrace of B-Movie horror titillation as he approached pubescence.

Courtesy the artist

“Who had time for sports when The Green Slime was playing at the Poly Theater just down the road on Vaughn Boulevard?” McCormick writes. “Who wanted to attend a church or a school function when Dracula Has Risen from the Grave?”

By the time he was old enough to get a job, McCormick — reminiscent of a young Quentin Tarantino — says he was unfit for anything outside a movie theatre. In 1975, he began work as an usher at Cineworld, Fort Worth’s first multiplex. And one day, at Eastern Hills High School, he met an incredibly talented kindred spirit. His name was Bob Camp. Bret and Bob and a small band of Eastern Hills amateur film aficionados began shooting Super 8 movies devoted to vampires rising from the grave, skateboarding werewolves, psychedelic hallucinations, and a Blob-esque stop-motion monster known as “Splot.”

After high school, McCormick briefly studied under filmmaker Andy Anderson (Interface, Positive I.D.) at UT-Arlington and then earned an associate’s degree from the Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara, California.

McCormick’s buddy Camp would go on to co-found and become a director for Spümcø, the animation studio that created the wonderfully raucous Ren & Stimpy Show, a brilliant, groundbreaking forerunner of so many of the animation series we see and love today. McCormick himself would chase the delightful B-Movie dreams that so enchanted his youth.

At the end of the day or, in fact, the second millennium, McCormick was burned out and frequently burned by double-dealing, middling movie distributors and ruthless, bottom-feeding con artists. He walked away from showbiz and didn’t reemerge in the filmic sense until Christmas Craft Fair Massacre.

“Rob Hauschild of Wild Eye Releasing sent a crew down to interview me for a special feature on the upcoming re-release of The Abomination,” McCormick said, “and I had a bizarre reawakening. I was excited to learn that their camera guy, Mark Polonia, had made over 80 features! … Somehow that meeting sparked my interest in learning how super low-budget movies were being made today. I found out that you could make feature films for practically nothing with your cellphone and edit your footage with free software available online. For the second time in my life, I was bitten by the movie bug.”

McCormick admits that Christmas Craft Fair Massacre was a test project, and the entire experience was positive.

“I’ve already earned more money from the movie than I spent making it,” he said with a laugh. “If that had been the case the first time around, I never would have stopped making movies. I realize my unconventional cinematic sensibilities aren’t for everyone, but if I can make a feature for less than $1,000 and immediately turn a profit, I find myself in a brave new world.”

Look for Christmas Craft Fair Massacre this Christmas season and an upcoming production with a working title of Attack of the Killer Cow Patties sometime next year.

McCormick can be reached at BretAnthonyMcCormick@gmail.com.

E.R. Bills’ feature on my friend Bret McCormick was excellent. This is this first feature I have actually read that was written in true journalist fashion. I was a feature writer in college and so I have an endearment to such articles. I have read others in other magazines that were difficult to follow somewhere the ball has been dropped in teaching journalism and the correct way of writing effectively. I am hopeful in seeing more efforts as these. Bret is a very talented man and has always had a penchant and talent for storytelling on film and in print. Keep up the good work E.R. and Bret.