I recently had a fender-bender smack-dab in the middle of Camp Bowie Boulevard, a minor collision that left the tail ends of both vehicles hanging out into the left lanes of the east- and westbound traffic.

No one slowed down, so I got out of my truck to wave off the traffic on the other vehicle’s side, and the other driver, a Latina, pulled onto the road I’d come from. I returned to my truck and parked behind her.

Unbeknownst to me, a Fort Worth police patrol car had arrived at the Sonic on that side road. The officer was responding to a call there, but he didn’t see our collision. He simply came over to make sure we were OK. The Latina and I were both fine, and so was her toddler, who had been properly strapped into a car-seat in her back seat. The officer had to finish addressing the incident at Sonic, but he took our license and insurance info.

The Latina and the child got back into her car, and she made a phone call. When the conversation ended, I walked up to her window. We exchanged phone numbers, and she seemed anxious. The car and the insurance were in her father’s name. I asked her if everything was OK. She smiled and nodded, but I could tell she was concerned.

At that point, I became anxious. What if she had a warrant? What if she was an immigrant and didn’t have her papers?

The officer hadn’t seen the collision and couldn’t assess blame. The insurance companies would battle it out. If the officer hadn’t been responding to another call, he wouldn’t have engaged us or asked for our licenses or insurance at all. I was suddenly concerned.

I walked over to the Sonic and asked the officer if he had a prybar I could use to try to bend my fender back out. He didn’t, but he said he’d be with us in a minute. As I walked back to our parked vehicles, I realized why I was concerned. The last thing I wanted to see was a young woman separated from her child for a fender-bender. If the officer returned and the Latina had a warrant or an expired green card, our mishap might result in her arrest. I didn’t exactly have flashbacks of brown children locked in cages at the Texas/Mexico border, but I knew with absolute certainty I couldn’t trust the laws of my state or my fellow Texans’ attitudes toward immigrants. And I knew I’d rather err on the side of human decency than Texas injustice.

I asked the Latina if she cared whether or not we included the officer in any kind of report. She said she’d rather not, unsuccessfully attempting to conceal her anxiety. I revisited the officer at the Sonic and told him that the Latina and I had exchanged info and that we didn’t require his assistance. He said her driver’s license was expired.

“You look like you got your hands full here,” I said, nodding at the Sonic. “We’re OK.”

“You sure?” he asked.

“Positive,” I replied, and he returned my license and walked over and spoke with the Latina briefly.

After the police officer departed, the Latina texted me to make sure I was OK. I assured her I was.

I reported the accident, and my insurance company told me to take my truck to a collision repair center actually owned by a sitting Republican U.S. Congressman. Sheesh, I thought, a politician who profited politically off brown children being locked up in cages would now profit from my accident. It didn’t thrill me, but I needed my truck repaired.

A week after I dropped it off, I received a call from one of the collision center’s supervisors telling me that the truck was torn down but the replacement parts were another three weeks out.

“Ever since Biden got elected,” he said, “we’re having all kinds of problems.”

At that point, I’d had enough. “If you think the election of President Biden is what’s causing supply shortages, then you haven’t got two brain cells left to rub together. The supply issues started during COVID under the previous administration.”

Silence.

I knew he’d misread my unmistakable Southern drawl and presumed too much. And I realized I’d just irresponsibly mouthed off to the guy in charge of fixing my truck.

“But this isn’t about politics,” I told him. “I understand.”

We finished the conversation cordially, but I was frustrated.

What happened to Texas, and what’s wrong with Texans? Is there any escape from conservative small-mindedness now? Doesn’t it permeate every aspect of our culture and manifest itself as bigotry, chauvinism, greed, ignorance, and xenophobia at every turn?

I suddenly recalled President George W. Bush’s remarks a couple of weeks after the Twin Towers fell in New York City in 2001. “They hate us for our freedoms,” he said.

It was laughable then, of course. They “hated” us because we routinely and covertly undermine their governments and overtly try to bomb them back to the Middle Ages for Big Oil. Bush’s comment was ludicrous then, but it’s spot on now — about us.

We really do seem to “hate us for our freedoms.” We hate fair elections, voting rights, health care, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, and education in general. We hate Muslims, LGBTQ+, Mexicans, Mexican Americans, Asians, immigrants, librarians, and Black people — unless they play football, basketball, or run track (and only then if they don’t kneel during the national anthem for a nation we hardly consider ourselves a part of). We care more about fossil fuels than fresh water, and we fight more for the rights of disturbed white males who envision themselves as the Punisher than any innocent Texas girl’s sovereignty over her own body.

Everything’s not bigger in Texas.

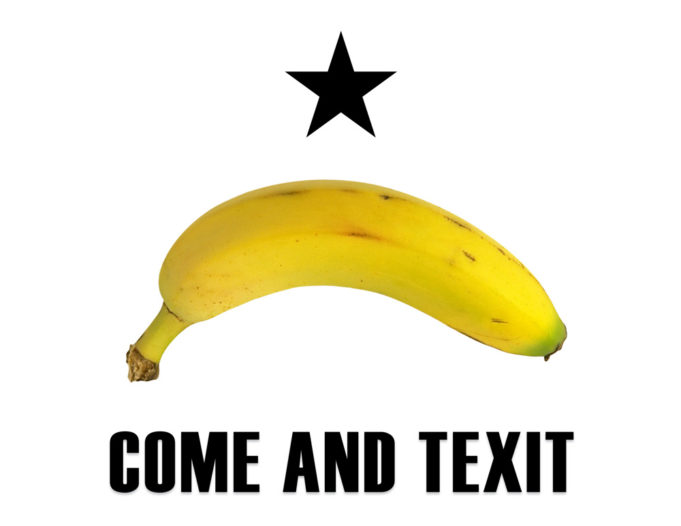

We’re a small-minded state full of small-minded, ignorant people. We despise American freedoms and ideals so much that we’re hardly even worthy of them anymore. And the new redophile political platform in Texas capitalizes on this perversity, delegitimizing the results of the 2020 presidential election and reiterating the Lone Star state’s right to secede from the United States.

Which sounds great if we’re aspiring to a Lone Star civil war or an imbecilic lapse into a bloviating banana republic (with an emphasis on already having gone fricking bananas!).

But Texit wouldn’t be a secession. It would be a cessation of human rights and human dignity for a large part of the population. — E.R. Bills

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is the author of Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious, The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas, and Texas Oblivion: Mysterious Disappearances, Escapes and Cover-Ups.

This column reflects the opinions of the editorial board and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. Submissions will be edited for factuality, clarity, and concision.

Are you such a closeted racist that it never crossed your mind that this woman was anxious because she had just been involved in an accident? Why would you go straight to her being undocumented and/or having warrants out for her arrest? I very much doubt that would have thought the same thing if the woman had been white….Would you have assumed that she was wanted, or that her “green card” was expired? Would you have felt the need to point out that her child was properly strapped in, as if that was irregular? Next time you feel the need to hide your racism by playing white savior, try not to make it so obvious.

Jeez! He was concerned for the safety of another human!

I doubt it…this is what implicit bias is. His own inherent racism likely led him to make negative assumptions (that she was an illegal immigrant and/or criminal) about her based on her race. But he then spins the story to make himself look like he is simply concerned for her. He makes no mention of any behavior from her that made her look like a criminal, he just assumed she was because of her race. Then he assumed that the cop was racist just like him (again with no proof that he was) and then talked her out of making a report. The whole story is either completely made up, or proof of his own implicit biases

Triggered much?