If you live in a place long enough, you begin to think you know it. Or that it defines you or becomes part of your DNA. And if you were born there, its role in your identity is official. But that certainly wasn’t how I felt at the March 8, 2022 regular meeting of the Hill County Commissioners Court in Central Texas, particularly when, after a pledge of allegiance to the American flag, we were expected to pledge our allegiance to the Texas flag. I didn’t even know Texas had a pledge of allegiance, and I certainly was never asked to perform one when I was in school. I didn’t even know the words. I just kept my right hand over my heart and mumbled through it.

It was off-putting, and I looked it up when I got home that evening. A pledge of allegiance to the Texas flag didn’t become official until two conservative lawmakers co-sponsored a bill requiring schoolchildren to recite it along with the national pledge in 2003. This surprised me. I’d lived my whole life in Texas and had no clue. So, there I’d been, standing in the galley of the Hill County Commissioners Court pretending to make the pledge with three Black women and two young Black boys.

*****

It all started in early January of this year when a 68-year-old Black woman named Crady Johnson contacted me about a piece I’d written in the Fort Worth Weekly three years earlier. “Dull in the Heart” is about Bragg Williams, an intellectually disabled Black man who was burned at the stake in Hillsboro, the Hill County seat, in 1919. My story had run close to the centennial of the incident, and Crady had just stumbled onto it. A lifelong resident of Fort Worth, Crady is Williams’ niece. She wanted to know more about me and more about what I knew regarding Williams. She and her 57-year-old sister, Tonya Camel, also a resident of Fort Worth all her life, had heard their Uncle Bragg was lynched, but their mother never talked about it much. My narrative of the events shocked them. Crady invited me to meet with her family at a restaurant in the Mid-Cities, and I accepted her invitation.

Photo by E.R. Bills

By the time we got together, Crady and some of Williams’ other relatives had done their homework. They knew I was the author of The 1910 Slocum Massacre: An Act of Genocide in East Texas (History Press 2014) and Black Holocaust: The Paris Horror and a Legacy of Texas Terror (Eakin Press 2015). They also knew I had worked with descendants of victims of the Slocum Massacre to attain the first state historical marker specifically acknowledging racial violence against African Americans in Texas. The meeting was somber but congenial. I shared what I knew, and they shared what they were aware of. I told them the “Dull in the Heart” piece was an expansion of an excerpt from Black Holocaust. We had a nice conversation about a dark subject, and we all learned some things. Then, they popped the question. They wanted to know what I thought about trying to erect a historical marker acknowledging Williams’ ghastly, extralegal execution in Hillsboro.

“We needed to do something,” Tonya said last week at our meeting, “because justice was never done, and Uncle Bragg never received due process, and nobody had to answer for it.”

“We don’t know what happened or whether Bragg was guilty or not,” added Letha Young, Crady and Tonya’s 81-one-year-old mother and a fan of TV Westerns. “The whole thing makes me think of Hang ’Em High with Clint Eastwood. He gets hung by some vigilantes for something he didn’t do, but the sheriff comes along and cuts the hanging rope loose before Eastwood’s character dies. Where was the sheriff or the police when Bragg was being burned alive on the courthouse square?”

I didn’t sugarcoat things. I told Crady and the others that it would probably be a long, difficult, uphill slog. What I didn’t tell them was that I wasn’t sure if I was really up for another contentious, time-consuming marker effort, but in a way, I felt obliged. I was the one who dug up a lot of this stuff. How could I not stand by it, defend it, and pursue the justice that my book Black Holocaust had called for?

How could I turn my back on them or this history?

Why were so many white Texans bent on turning their backs on this kind of history?

*****

In the early afternoon of Dec. 2, 1918, Annie Wells and her son Curtis, who was almost 5 years old, were beaten to death at their home near Itasca. The husband and father, George Wells, had gone to Hillsboro, and the older Wells children were in school not far away. Annie and Curtis’ attacker killed them and then carried their bodies into the Wells residence, setting it aflame presumably to destroy any evidence.

Neighbors and the older Wells children, who were on their way home from school, saw smoke from the fire and retrieved the mother and son’s remains before they were badly burned.

The details of the case according to the Jan. 18, 1919 edition of the Hillsboro Mirror are noted here:

Along the latter part of November, the Wells family was preparing to use their automobile, and a negro [Bragg Williams] working for them was starting the car, when he charged [accused] Mr. Well’s [sic] little boy [Curtis] with stopping the engine and the boy kicked him. The negro kicked him back and was discharged. On the second of December, while Mr. Wells was in Hillsboro the negro returned to the Wels [sic] home, and, according to the negro’s story, Mrs. Wells asked him what he wanted and he told her work. She asked him why he kicked her son and began abusing him and struck him in the head with a broom she held in her hand. He grabbed the broom and she reached for a gun standing on the gallery. The negro beat her over the head, knocking her down and then hit her over the head twice more. Mrs. Wells [sic] little four-year-old son then started for the school house which was only a few hundred yards away, and the negro started after him and hitting him over the head with the gun. Finding both mother and child dead, the negro drug both into the sitting room and piling cotton between them, set it on fire. He then went into the garage, which was built onto the house and to make sure of the burning of the building and thus destroying the evidence of his crime.

The Mirror reported that, afterward, Williams went home, picked some cotton, and was arrested by “Sheriff J.W. Martin” later while chopping wood. The Mirror’s report then stated that Martin and his wife (and someone named “Earl Pruitt and his wife”) transported Williams to Hillsboro to turn him over to the local police.

The tale of the transport reads more like a Sunday drive than the conveyance of a cold-blooded murderer to jail. Accounts, however, vary.

Described by the Waco News-Tribune as “tall and ungainly, and seemingly of low mentality,” Bragg Williams was apparently taken into custody from the home he shared with his parents approximately three miles from the Wells residence, but before there had even been an official accusation made, a group of Hill County citizens attempted to lynch him, and Martin (with or without his wife and Earl Pruitt and his wife) had delivered the suspect to the home of a local attorney named W.C. Wear instead of directly to the county jail.

Martin solicited Wear’s opinion as to whether or not Williams could have been the perpetrator of the crime and asked Wear to prepare a written statement for Williams to sign. Wear went to Martin’s patrol car and asked Williams to make a statement, and the suspect reportedly complied.

After hearing Williams out, Wear made remarks to Sheriff Martin that were disturbing. Based on his writings, he told Martin that “the people of Itasca community would come down before morning and kill the son of a bitch and they ought to kill him.”

Wear insisted that “there was probably nobody in Texas more opposed to mob law than he, yet the facts as detailed by the defendant was [sic] so horrible that in this instance he felt an impulse himself to mete out speedy punishment.”

Martin asked Wear what he should do with Williams, and the attorney was unequivocal. He said if Williams was placed in the Hill County jail, “he would be killed before morning” and others may be as well. Wear advised Martin to take Williams to Waco.

In early January 1919, Wear was asked by the Hill County District Court to defend Williams, but on Jan. 11, Wear formally recused himself. The lawyer’s recusal was appropriate and necessary, especially, perhaps, due to his expressed personal feelings of the incident as communicated to Martin, but Wear had also complicated the task of defending Williams by sharing the details of Williams’ pre-Miranda, reportedly incriminating statement to others in Hill County. And this fact is recorded in Wear’s official recusal request, the writings referenced above. He said the incident was so “unusual” that he referred “to the matter and made statements to various and sundry people as to what occurred.”

On Jan. 13, 1919, Texas Governor William P. Hobby received an urgent communication requesting Texas Rangers to protect Williams. The message stated that “the prisoner was in imminent danger of being lynched,” and the local sheriff (who was apparently named James Yancy McDaniel, not “J.W. Martin”) had declared that not only would he not stop white citizens from lynching Williams, but he also opposed any attempt by Texas Rangers to protect the suspect. Governor Hobby sent Texas Rangers and they transferred Williams from Waco to Dallas, where he remained until his trial date. On Jan. 16, 1919, Williams was escorted back to Hillsboro by the Texas Rangers and his trial began.

After Wear’s recusal due to an arguably unconstitutionally procured confession and the irresponsible dissemination of the details of the reported confession, two highly regarded Hill County attorneys — Walter Collins and Albion M. Frazier — were appointed by District Court Judge H.B. Porter to defend Williams, and they did so under protest. They requested a change of venue for the case (in light of the certainty that the information that Wear shared rapidly spread through the county), but it was denied. As the prosecution and defense seated a jury, Williams sat in the courtroom under the constant guard of six Texas Rangers.

Collins and Frazier entered a plea of “not guilty” for Williams by reason of insanity and, interestingly, protested the nomenclature of the case, The State of Texas vs. Bragg Williams, alias Snowball. Williams apparently regularly wore faded khaki coveralls, and locals reportedly referred to him as “Snowball.” In many settings, this alias arguably would have constituted a term of scorn or derision, perhaps especially to adult Black men of the period. The court’s insistence on using it suggests a broad local familiarity with Williams, a possible pet nickname, and arguably the kind of label a Black man of “low mentality” may not have minded, but for Collins and Frazier, it was at least a passive-aggressive form of denigration and had no reasonable bearing on the case.

In terms of the defendant’s plea, not guilty by reason of insanity, Collins and Frazier specifically noted that “malice aforethought, which is absolutely essential to constitute murder, is where one with sedate, deliberate mind and formed design unlawfully kills another.”

Collins and Frazier argued that Williams was intellectually disabled and that the evidence presented in the case would not rise above the threshold of reasonable doubt. They suggested that Williams’ stunted intellectual capacity made him incapable of murdering someone with a “sedate, deliberate mind” and “pre-formed design” and pointed out that — considering the defendant’s intellectual disability — if Williams had, as accused, slain Mrs. Wells, it could have been only due to a perceived threat as interpreted from his limited, cognitively impaired perspective. This technically qualified the acts Williams was accused of as self-defense. This exact narrative was conveyed in the Hillsboro Mirror. The afore-noted excerpts from the Jan. 18 edition of the Mirror, which were based on the confession that defendant Williams allegedly gave Wear (and which Wear admittedly spread), state that Mrs. Wells attacked Williams with a broom, which, in a cognitively impaired person’s mind, may have constituted an imminent threat or have compelled a defensive response.

County Attorney Earl E. Carter and Assistant County Attorney H.P. Shead, however, were familiar with Williams’ “low mentality” and anticipated the defense team’s plea. The prosecution prepared a professional refutation. They brought in a Fort Worth alienist (the term for a psychiatrist or psychologist in those days) named W.B. Allison. A practitioner at the Arlington Sanitarium in Tarrant County, Allison was born in 1879 in Falls County, a hotbed of racial violence during Reconstruction and well into the 1890s. He undermined the defense team’s insanity plea before the all-white, all-male jury.

Williams never testified in court, but a sizable portion of the community must have been aware of his statement to Wear and he did apparently return to Hillsboro in the same khaki coveralls that he had left in — the coveralls that identified him as “Snowball.” The prosecution subsequently produced two white female witnesses who said they saw a Black man in “yellow” coveralls heading in the direction of the Wells residence before the murder and a young Black girl, Smithy McDuffy, who claimed she saw a Black man in “yellow” coveralls running from the direction of the residence after she had heard the screams of Annie Wells.

A white jailer named Jess Vanoy testified that Williams had blood on his coveralls and shoes (presumably after Williams was apprehended). Williams’ brother Natural was then summoned, and he testified that Bragg had blood on his shoes the day he was captured — but didn’t mention anything about blood being on his coveralls. All of which, of course, begged important questions. If the Hillsboro Mirror account of the crime was even remotely accurate, why wouldn’t Sheriff Martin, Mrs. Martin, attorney Wear, and Earl Pruitt and/or Mrs. Pruitt have been subpoenaed to confirm reports of blood on Williams’ person — especially if he was wearing khaki coveralls, which would have made any amount of blood obvious?

Also, the details of the murder weapons were contradictory. The Mirror reported that Williams dispatched Annie Wells and her son Curtis with the butt of a shotgun. The court files indicate the weapons used to murder Annie Wells were the butt of a shotgun and a sharp instrument. The sharp instrument was never discovered or produced.

On Friday, Jan. 17, Williams was convicted of murder, and the Texas Rangers were abruptly and surprisingly instructed to depart. Williams — arguably because he did not fully grasp the implication or the gravity of the court’s verdict or sentence — laughed. The defense team’s argument that Williams was intellectually disabled is perhaps nowhere better illustrated than with this laugh. The year was 1919, and the white-owned, white-run, and white-staffed newspapers at the time would have focused on Williams’ laugh if it had been in any way malicious, ill-intended, or otherwise contemptuous or defiant, but no such reporting exists.

On the morning of Monday, Jan. 20, the court reconvened for sentencing, and Judge Horton B. Porter condemned Williams to be hanged by the neck until dead on Feb. 21.

What happened next was completely unexpected.

Collins and Frazier had defended Williams under protest, and his guilty verdict was not an unpopular result. Once it was handed down and the death sentence was imposed, however, the two attorneys deemed it unjust due to the defendant’s limited intellectual capacity and promptly requested a retrial. And when their petition for a new trial was denied, they immediately filed a notice of appeal to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals.

At approximately 11:45 a.m., a mob — upset by the appeal and no longer in the mood for due process — assembled at the Hill County Jail and demanded Williams be handed over. The jailers refused to give him up, so the mob battered the jail door down, stormed the facility, and seized Williams from his cell. The mob then dragged him to a concrete “safety first” post at the intersection of Elm and Covington streets on the southwest corner of the courthouse square.

Courtesy of Wikipedia Commons

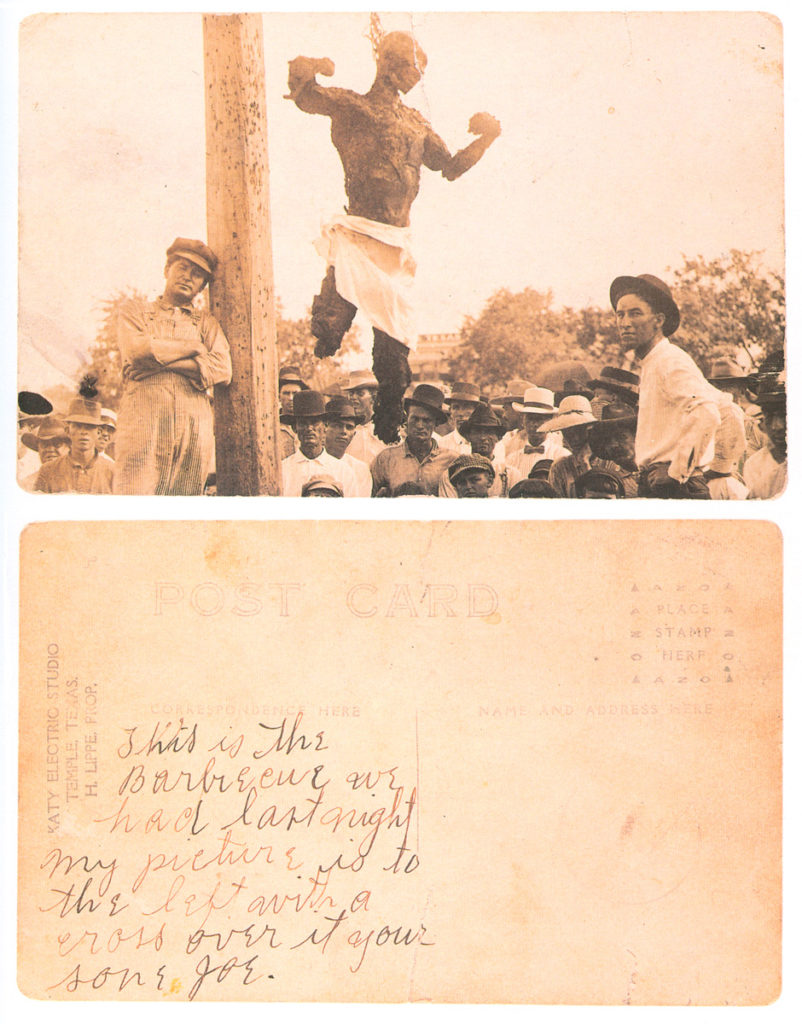

A cadre of enthusiastic vigilantes quickly collected hay, wood, and coal and piled them around Williams, dousing the combustibles in coal oil. A match was then applied, and the conflagration killed Williams in a matter of minutes. Though he put up no resistance, he was heard to exclaim, “Help me, Cap” three times before the flames consumed him. Williams’ body was reportedly left in the embers of the fire for hours. Photographs were taken of the atrocity, and one Hill County lawyer is said to have kept one of the images framed in his office for decades.

*****

On Jan. 21, Gov. Hobby denounced the lynching and initiated steps to investigate it. The next day, he sent a message to the Texas Legislature requesting a law that would put an end to mob violence and correct the assumption that members of white lynch mobs are not prosecutable. Hobby’s request was echoed by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), who sent a telegram to Hillsboro officials demanding punitive measures against participants in Williams’ lynch mob.

On the same day, the San Antonio Express published a condemnation of the Hill County court’s decision to dismiss the Texas Rangers after the conviction. “If ever there was a fatal error of official judgment — whoever was responsible therefore — it was in this case. If ever there was a warning of lynching attempts, it was in this case.”

On Jan. 23, Hobby instructed Texas Attorney General Calvin M. Cureton, First Assistant Attorney General W. A. Keeling, and E.A. Berry, Assistant Attorney General to the Court of Criminal Appeals, to initiate an investigation into the lynching of Bragg Williams.

A Hill County grand jury subsequently examined charges against members of the lynch mob but adjourned without returning bills of indictment. After the state investigation initiated by First Assistant Attorney General Keeling, Attorney General Cureton and Assistant Attorney General Berry filed a motion to cite 12 members of the lynch mob (Jud Rufus Beavers, Will Browning, Joe Ferguson, Cole Hammer, Earl Hobbs, Jim Hobbs, William Pinckney Hightower, E.L. Stroud, George Wells, William R. Wells, Poly Wilson, and Wiley Wilson) for contempt of court in regard to the Court of Criminal Appeals motion, because the vigilantes had lynched Williams after his appeal had been filed and was technically pending.

The effort was a well-conceived attempt to prosecute members of the lynch mob in a higher court, especially as it was obvious that they would not face prosecution in Hill County. The motion was described as the first of its kind in Texas, but it, too, fell short. No action was taken on the motion in March or April, and the attempt quickly faded into obscurity.

*****

When I spoke to Crady, Tonya, their mother Letha, and several other family members in late January, they hadn’t even been aware that Bragg Williams was intellectually disabled. Their family had fled Hill County after his horrific lynching, and no one talked about it a lot after. One story that survived was of Williams’ mother walking several miles with one of his infant siblings on her hip to visit him at the Hill County Jail. Upon arrival, she learned that he’d been transferred to Dallas. The Hill County authorities hadn’t even notified his family.

Crady, Tonya, and Letha didn’t procrastinate. They quickly decided to pursue a historical marker acknowledging the lynching and enlisted me to help write the marker application. When we first appeared at the Hill County Commissioners Court a little early on March 8, one of the commissioners asked us why we were there. When we told him why, he said we weren’t on the docket and that we wouldn’t be able to address the court. The court clerk we approached to verify this claim informed us that this was incorrect, so we seated ourselves in the courtroom and waited. It was an inauspicious beginning.

Photo by E.R. Bills

After the two pledges of allegiance and regular county court business was concluded, I addressed the Commissioners Court and explained our intentions. County Judge Justin Lewis and the commissioners present didn’t seem completely amenable, but they weren’t openly hostile either. And, afterward, Judge Lewis, 45, came over and talked to Crady, Tonya, Letha, and me and admitted that a cruel injustice was committed in Hill County after the Bragg Williams trial and that he didn’t think we would have any problems procuring a marker. I was skeptical, but Lewis seemed amicable and straight shooting, and we appreciated his speaking with us.

On April 5, I submitted the preliminary marker application (with Crady Johnson listed as the primary sponsor), and on April 18, the Hill County Marker Chair, Jana Burch, let us know that the marker narrative was missing a context section, that there was no evidence that Williams was intellectually disabled and that the application needed to be better documented. It frustrated us, but we dug deeper, went to some lengths to substantiate claims of Williams’ cognitive impairment, and addressed the documentation issues. The marker application increased from 10 to 21 pages, and we resubmitted it.

*****

For a discussion regarding the context of the Hillsboro lynching of Bragg Williams, it is necessary to examine the history of lynching in the region and, perhaps specifically, burnings at the stake.

On July 22, 1910, Henry Gentry, an 18-year-old Black suspect accused of “peeping” at a white woman through a window in her home and killing a constable, was stripped naked, dragged around the Bell County courthouse square by a horse at full gallop, and then burned at the stake on the courthouse grounds. On July 31, 1915, Will Stanley, a 31-year-old Black suspect accused of murdering three white children, was shot and dragged through a fire repeatedly until the hellish flames silenced his cries and moans. And on Monday, May 9, 1916, Jessie Washington, another reportedly intellectually disabled 18-year-old African American man accused of bludgeoning a local white woman to death, signed his “X” to a confession he couldn’t even read. Washington was arrested, indicted, tried, and convicted, but, before the presiding judge could even record the speedy guilty verdict, a large man in the rear of the McLennan County court room shouted, “Get the nigger,” and a mob seized Washington. They burned him at the stake as the Waco mayor and chief of police watched on.

There were other disturbing incidents in the Hillsboro area as well. A Black suspect named Zeke Hadley was lynched on June 23, 1884, for the suspected rape of a white woman, and Hill County citizens attempted to lynch Isaac Bruce, a twentysomething Black man falsely accused of raping a white girl in 1892. Though the attempted lynching of Bruce was unsuccessful, some of the same men who tried to lynch him served on the all-white, all-male jury determining his fate. Bruce’s defense team presented credible witnesses and mounted a strong defense, but the jury found Bruce guilty, and the presiding judge sentenced him to death. An all-white court of criminal appeals subsequently affirmed the conviction, but, in mid-May of 1893, Texas Governor James S. Hogg commuted Bruce’s death sentence to life in prison “to spare his life and await future developments.” Hogg’s instincts were correct. Bruce was later pardoned and released.

These incidents and numerous others all have some bearing on the general proclivity for the white citizenry in Central Texas to conduct or condone grotesque lynchings in that era, but the underpinnings of Hill County race history are even darker. For example, examine the page on the Hill County Rebellion in the Texas State Historical Association’s Handbook of Texas.

HILL COUNTY REBELLION. During Reconstruction Governor E.J. Davis and the Radical Republican-dominated Twelfth Legislature of 1870 attempted to control crime in the state. In October 1870 Davis threatened Hill County with martial law for its tolerance of criminals. Conditions in the county seemed improved by late 1870, but in December a freedman and his wife were murdered in neighboring Bosque County, and State Police Lt. W.T. Pritchett moved into Hill County chasing suspects James J. Gathings, Jr., and Sollola Nicholson. Pritchett raised the ire of James J. Gathings, Sr., by seeking to arrest his son. The elder Gathings, Hill County’s largest landowner, incited a mob that pushed county officials to arrest and detain the State Police troopers in Hillsboro in early January 1871. On January 11 Davis declared martial law in Hill County and dispatched Adjutant General James Davidson and the State Militia to rescue the jailed police. …

This “General Entry” citation contains mistakes and leaves a lot of the story out.

First, Hill County’s “tolerance of criminals” especially favored acts of violence against persons of color. Second, the December double murder didn’t befall “a freedman and his wife.” It was Joe Willingham and the wife of Lewis Willingham, both longtime, peaceable residents of Meridian, Texas. Third, on June 18, 1870, a Black man named Thomas Tanner was murdered in Hill County, and six other African Americans — Tanner’s neighbors — fled to McLennan County, declaring “that no protection was afforded to blacks” in Hill County and that they were afraid to stay there. And, fourth, after whites burned down a Black school near Towash on Oct. 21, 1871, Hill County could no longer hire or retain qualified instructors. During the same period, whitecappers (terrorist precursors to the Ku Klux Klan) actually ran a Black man out of Hill County for engaging in a dispute with a white man. And it was not uncommon for whites in some Central Texas counties to try to expel all Blacks from county boundaries altogether. Hill County never officially went so far as that, but the lawlessness it permitted against its Black citizenry was as effective as doing so. As Barry Crouch and Donaly Brice state in The Governor’s Hounds: The Texas State Police, 1870-1973, “Hill County blacks, although they composed but a fraction of the total population, found themselves on the receiving end of outrageous acts” of murder and terrorism — and the perpetrators of those acts were never held responsible or punished.

Image courtesy Portal to Texas History

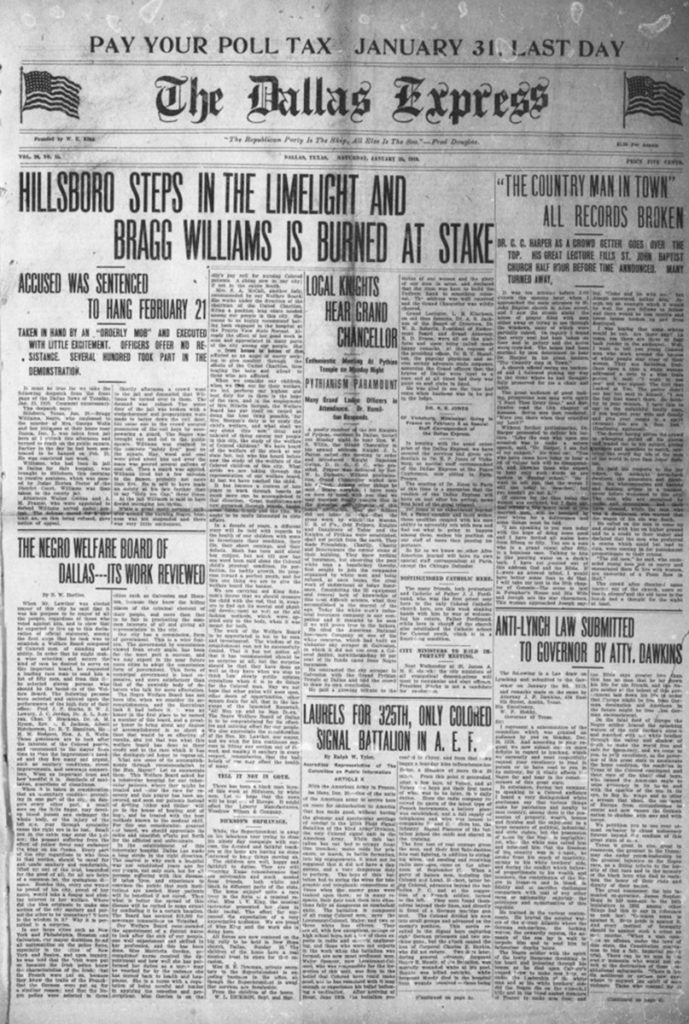

The burning of Bragg Williams at the stake didn’t happen in a vacuum. As the front-page headline in the Dallas Express on Jan. 25, 1919, put it, the Bragg Williams lynching simply allowed Hillsboro to step “into the Limelight” of white primacy. The burning of Bragg Williams at the stake was the first major racial incident in Texas in 1919, and it was the first lynching mentioned in the NAACP’s historic 15-page pamphlet An Appeal to the Conscience of the Civilized World (February 1920).

*****

On April 28, Crady, Tonya, Letha, and I resubmitted the application and then got back on the schedule to meet with the Hill County Commissioners Court for their permission to place the marker on the courthouse square (so our marker application could be forwarded to the state). In the interim between our appearances, a white woman named Katie Schatzlein reached out to me after reading Black Holocaust and shared a story. Schatzlein said that when the Hill County Courthouse burned on New Year’s Day in 1993, she telephoned her mother to express what a shame it was, because she thought the Hill County Courthouse was one of the most beautiful buildings of its kind in Texas.

“Knowing nothing of the history of the Bragg Williams lynching,” Schatzlein says, “I expressed sadness at the courthouse’s loss.”

Her mother’s response was shocking. “That’s when [my mother] said, ‘Perhaps it’s poetic justice or karma.’ ”

And then the mother broke down and shared the whole story. Schatzlein’s mother told her that her grandfather had participated in the Bragg Williams lynching and drank himself to death at 51 years of age, perhaps because of his guilt. Schatzlein asked her mother why she never told her, and the mother said it was because of the guilt that she, herself, had always felt. The mother lamented the fact that she had never done anything about it, but she said she was telling Schatzlein now because perhaps she could do something.

When Crady, Tonya, Letha, and I appeared in front of the Hill County Commissioners Court again on May 8, I still didn’t know the pledge of allegiance to the Texas flag, but I planned to share Schatzlein’s story. We all prepared ourselves to speak, but we never got the chance.

Photo by E.R. Bills

When Court Item No. “8. Discuss and/or approve for permission of Property Owner for Historical Marker placement” came up, there was no “discussion” at all. Judge Lewis immediately called for a vote, and the board approved the motion unanimously.

Crady, Tonya, Letha, and I were surprised. Each of us, in our own way, had prepared to make compelling remarks before the decision was put to a vote.

“I had prayed the night before,” Crady said. “I had prayed that the words that came out of my mouth would be Godly words, words of forgiveness, words of love and compassion. I had prayed that whatever I said would be a reflection of my God.”

After the Hill County Commissioners Court’s affirmative vote on the location of the marker, Tonya sensed that something larger was at play. “It was divine intervention.”

Crady concurred later in a phone conversation. “Even in the midst of all the anger and bitterness and strife and hatred we see these days, God is working, and not just for Uncle Bragg’s family but for the people of Hillsboro.”

In another phone conversation, Tonya added, “I think they needed justice, too. And maybe closure. It was a spiritual, humbling experience.”

The work isn’t complete. According to Hill County Marker Chair Burch, the Bragg Williams Lynching historical marker application that we submitted has been sent to the Texas State Historical Commission for review and approval or disapproval. We are cautiously optimistic, and we expect a response later this year. To me, the state of Texas seems no more ready for the truth about acts of white terror than they were when the Slocum Massacre marker was approved and placed on Jan. 16, 2016. The atmosphere in Texas seems more hostile. One indicator is that all the casualties of the Slocum Massacre are still piled up in unmarked mass graves in the Slocum area, but the history of the Slocum Massacre and the burning of Bragg Williams at the stake (and so many others) is not going away. And wishing won’t make it so. And neither will trying to prevent it from being taught in schools or read in libraries. This history is here to stay, and the best way to deal with it is by being on the right side of it.

Hillsboro really seems big enough for that. Is Texas?

If not, why are we expected to pledge allegiance to its flag?

Fort Worth native E.R. Bills is the award-winning author of the aforementioned books and several others, including Texas Obscurities: Stories of the Peculiar, Exceptional and Nefarious (History Press 2013) and Texas Far and Wide: The Tornado with Eyes, Gettysburg’s Last Casualty, the Celestial Skipping Stone and Other Tales (History Press 2017).