A memory that has always stuck with me from childhood days spent at the Southwest Baptist Church of Desoto, Texas, is the voice of a tiny, elderly woman saying that the only thing you can really do to help people find God is to “bear witness” to your own experiences with Him.

This point was made softly and in one of the sweetest voices I’d ever heard. Maybe it was the contrast of her tone to the usual bravado in the church (where no women were allowed to preach), or maybe it was because that was the first thing I’d heard about religion in a while that really made sense to me. (Those WWJD bracelets were a high commodity at the time.)

Whatever it was, her wise words of empathy and communication found a foothold within me to this day, as I try to “bear witness” to another experience that also feels impossible to explain to those who haven’t felt it first-hand.

When I was 14, I was raped at a party. A boy I thought I knew — or maybe I should say “man,” as he was a few months shy of his 18th birthday — raped me behind the locked door of an absent parent’s house while I was drunk and screaming.

The rapist said he wanted to show me his guitar in the other room because I was learning to play. We started kissing, and then when I tried to leave, he wouldn’t let me. Like most men, he was physically stronger than I was when I tried to fight back. Nobody heard my screams over the music, or at least nobody cared.

The most striking thing about that time in my life was how normal it felt. This was the late ’90s, when the culture was steeped in the toxic fumes of “artists” like Marilyn Manson, Fred Durst, and Eminem. I remember being frequently disgusted at how even lesser chauvinistic artists like Bradley Nowell used dehumanizing lyrics toward women at every turn. Many films from this time period also portrayed women almost exclusively in subservient caretaker roles.

My dad was a long-haul truck driver, and my mom was depressed much of my life due to his abuse and control of her as a stay-at-home mom and housewife dependent on his income. Every time she tried to get a job, he would thwart her in some way to keep her subservient. According to my dad, East Texas would solve all the problems brought onto our family by the sinners of the big city. I realize now this was mostly code for: It’s cheaper to live there.

I repressed the gnawing ache of my rapist’s violation with the usual illicit teenage coping mechanisms. When trauma is repressed, the brain must bury the icy blocks deep from the mind for the system to keep running, generating the energy to go on. I started to throw up in the morning, becoming forced to also purge the truth of what happened to me.

Despite her depression — or, in hindsight, probably because of it — my mother was always a deeply caring woman. We filed charges against my rapist and soon found out I was pregnant. The police officers at the station were mostly focused on why I hadn’t come forward immediately “if that’s what happened.” I couldn’t seem to articulate the repression of trauma to them in a way that came across as sufficient.

We found out shortly thereafter that the rapist was already in jail in another county for felonious warrants, and so my assault was simply added to his list of charges.

I remember when I first found out I was pregnant. I didn’t even think about abortion as it was still whispered in the dark corners of Texas in the 1990s. I remember just accepting with mind-numbing certainty that my life was over. I prayed to God to help me be OK in life despite being a child with a child. The bright future I had imagined in neon colors was abruptly reduced to dull tones of survival.

My mom became my hero when she told my dad I was not having the baby of my rapist. My dad told me in a phone call from another state that he just wanted me to know that I’d “have no innocence left” if I decided to go through with it.

It felt as if because I failed to defend myself against my attacker, this is what I deserved — and I wasn’t his daughter anymore because of it. I failed to control my rapist’s power over my body, so now I must further lose control over my body to win my dad back.

But, really, what I see all these years later is that what my dad had failed to do was instill in me the fear of others he had (and also connect with me on an emotional level). My father was scared of a cruel world he didn’t really understand — in his defense, he was raised in a much more abusive home than I had ever known — and so for lack of answers, empathy, and communication, he needed his daughter to be scared, too.

Fortunately, I saw through the fear tactics and for whatever reason was immune to them. Maybe it was because my mom was a fighter on her good days, and because she was the more joyful of the two, I wanted to be more like her. Regardless of where it came from, this courage is what had made him see me as bad, but deep down, not bad but really scary, and scary is worse than bad.

Not because I didn’t trust people but because I did. Trusting people is what made me devoid of innocence? Searching for the good in others made me bad? This is something that will always scare the people who love you but feel too scared and confused by the injustices of the world to actually protect you. As clear as this contradiction in his words was, I still couldn’t see it for what it was at the time. I just thought I was bad.

This is what the system does when it demonizes abortion. It makes women think they are bad, that they are to blame for their rape or abandonment. They must not have wanted bodily autonomy if they got themselves into this situation in the first place, so what’s the problem with us taking it now? They must not have had enough pain to make them fearful, so this pain is now deserved.

But the truth is this: Men who support these fear tactics are scared of women. Scared of not understanding women because they lack empathy. Scared of their own lack of control over their own bodies when they want sex. Scared that if they lose control and rape, they’ll lose even more control if the woman has a choice about the product of that rape. Scared if women are not made to breed, they will take over and then men might have to know what it feels like to be treated the way they have treated women. But most of all, scared of women they can’t scare.

Throughout history, men have used brute strength and violence to control women. Then it was pregnancy or both. Now that most women are on birth control and have access to resources like Plan B and Mifepristone, which works up to 10 weeks after conception, only women in the direst of circumstances like rape and severe poverty seek surgical abortions.

Imagine a situation so financially dire, you can’t get together $300 dollars in two months to obtain the abortion pill. Or maybe a situation where you’re trying desperately hard to trust the man who impregnated you to be a partner, only to confirm it would be more of the same daily sacrifice from only you, further depriving the children you already support on your own of resources forever scarce. So desperate that you’ve repressed the memory of your rape until it becomes physically ejected from your mouth in undeniable tragedy.

These scare tactics are affecting only women who need access to abortion the most. Women who want nothing more than to get out of poverty but can’t due to abandonment by men they trusted because they’re resisting cynicism at all cost to remain hopeful of a better life for their children. Because that’s what mothers must do to raise joyful children — sustain hope in humanity.

I got my joy, courage, and hope from my mother, and despite all the pain I’ve endured because of these traits, they still shine vibrant in my life today. And now those traits shine bright in the eyes of my two daughters, too.

Anyone who truly listens to the individual stories of these women bearing witness to their experiences must know that this is a war on women, not a war on abortion. In my story, rape almost destroyed my life, and having the choice of agency over my body saved it. I mean this metaphorically, but it also could have been physically as I weighed 90 pounds at the time.

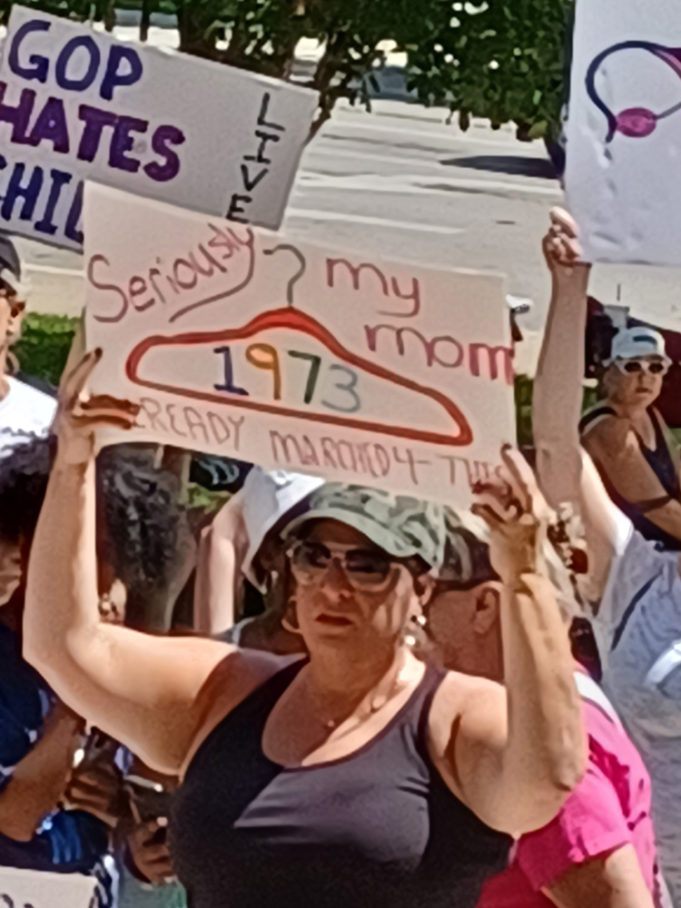

The fact is that there will be real deaths if Roe v. Wade is overturned just like there was before we had a choice. A real child like I was might lose her life for a clump of cells that is not alive, that very well could be a miscarriage, stillbirth, or some other tragedy.

We will never be able to control the tragedies we don’t know yet, but for now at least, we sure as hell can control the ones we do — as long as we’re not scared.

This column reflects the opinions of the editorial board and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. Submissions will be edited for factuality, clarity, and concision.

Well said.

Thank you:)

Sometime decisions are made and no one wants the consequences that come with it. It is never that babies fault.

Are you suggesting she somehow made a decision in her own rape?

Well stated!!! Thank you for sharing. An yes, mean are afraid of women.

Gabby: thank you.

Joanna: thank you.

the future is female. BRAVE females.