Whether presiding over civil, criminal, or family cases, judges are the only elected or appointed officials in this state who are afforded the power to unilaterally deprive Texans of property or liberty. For that reason, among all elected officials, judges are held to the highest ethical and legal standards.

The rulings of judges who fail to file their constitutional oaths and other mandated government documents as prescribed by law can be challenged through the court appeals process. One such appeal filed by former Tarrant County Justice of the Peace Jacqueline Wright argues that a retired visiting judge unlawfully presided over her recent criminal case.

In 2018, District Attorney Sharen Wilson sought the indictment of Wright for fraud. DA investigators found that Wright was not residing in the home that held her homestead exemption as required by law. The former JP’s friends and family maintain that Wright was targeted by Tarrant County Commissioner J.D. Johnson, whose son, Constable Jody Johnson, was allegedly tired of working under Wright. Jody’s recent loss in the Precinct 4 commissioner’s primary race to fellow Republican Manny Ramirez is widely seen as a public referendum on decades of alleged graft and misuse of government resources by the Johnson family (“Betting on the Good Old Boys,” Dec. 15).

When Wright’s case came to court in late January, the DA’s public integrity unit revised the charge to three counts of tampering with a government document, even though Wright claims she never altered the homestead exemption document in question. In early February, a jury found her guilty on all three counts, and retired visiting Judge Daryl Coffey, who presided over her trial at the request of District Court Judge Robb Catalano, sentenced the former JP to four years of probation and 10 days in county jail. Catalano stated on a court document that he would be on vacation during Wright’s trial, though he was present throughout the proceedings. The county court spokesperson has ignored my questions regarding Catalano’s presence during his supposed vacation.

Wright declined to comment on this story, citing advice from her attorneys, but court documents show Judge Coffey has a history of skirting the state Constitution and Texas statutes by filing questionable government documents and even misrepresenting himself as a senior judge.

The distinction matters because only Texas Chief Justice Nathan Hecht can grant senior status to retired judges, but Judge Coffey never complied with the statutes that require judges to file the correct forms after retiring and so was never granted senior status.

In an email, Coffey said that he has never represented himself as a senior judge, but government records reveal otherwise.

David Evans, Presiding Judge of the Eighth Administrative Judicial Region, assigned Coffey at Catalano’s request to oversee Wright’s case as a senior judge, based on court documents I reviewed.

Evans declined to comment on this story but said he would discuss the case once Wright’s appeal is settled. Coffey said the terms “retired” and “senior” are often used interchangeably by attorneys and judicial officers, but the designations are starkly different, based on state constitutional law.

Chief Justice Hecht can assign senior judges to any court in Texas outside the region where the judge resides, while retired judges are generally assigned to courts within the region where they reside.

In the order, Evans also mandated that attorneys representing the defense and prosecution be given notice of Coffey’s assignment.

“I did not know [Coffey] would be presiding over the trial until we saw” him the first day in court, said Michael Kelly, Wright’s attorney.

Coffey said in an email that he was fully qualified to preside over the case. He responded to several questions via email but declined to comment on the Wright case.

Courtesy of Tarrant County

Evans’ labeling of Coffey as a senior judge follows a pattern started by Coffey and allowed by Evans and Tarrant County’s Republican leadership in the years since. The misrepresentation dates to 2014, when Coffey resigned as a longtime misdemeanor court judge and stated his intention to serve as a visiting retired judge in North Texas and retired senior judge throughout Texas. Based on court records, Coffey drafted a letter to Chief Justice Hecht that year requesting assignment as a senior judge, but when I forwarded one supreme court spokesperson a copy of that letter, I was told that Hecht’s office never received Coffey’s request for assignment after retirement.

Texas courts are divided into 11 regions, including the Eighth Administrative Judicial Region, where the validity of Coffey’s ongoing status as a retired, non-senior judge may be void.

State law requires retired judges who elect to continue service to execute and file the two constitutional oaths with the presiding judge of the region as part of the process of verifying that retired judicial officers are qualified for the position that fills temporary court vacancies.

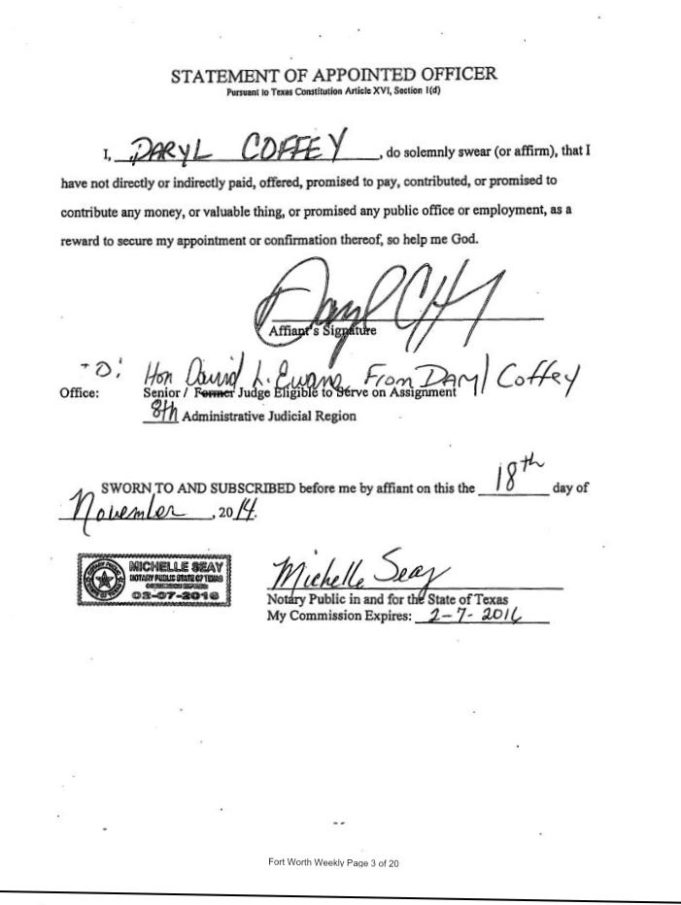

The first oath that Coffey signed on Nov. 18, 2014, the Statement of Appointed Officer, is an anti-bribery document that must be signed and filed before the judge can take their Oath of Office. Both oaths were revised by constitutional amendment in 2001, and Coffey failed to use a valid Statement of Appointed Officer oath when electing to serve as a retired judge, based on my side-by-side comparison of the document filed by Coffey and the requisite Statement of Appointed Officer oath on the Secretary of State’s website. The form he used does not contain the following language that was added in 2001: “Under penalties of perjury, I declare that I have read the foregoing statement and that the facts stated therein are true.”

On the anti-bribery statement, Coffey listed his status as “senior judge.”

The Oath of Office can be taken only once a valid anti-bribery statement is filed, meaning the only oaths Coffey has on file since his retirement in 2014 may be void.

In 1951, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in Brown v. State that judges must use the most current constitutional oath or their rulings are void, but there is another problem with the oaths Judge Coffey filed with Evans, that being that they were executed before he left office as an elected judge. Oaths are valid only when the position they were filed for exists — for Coffey, his retired judge position did not exist until Jan. 1, 2015.

On Nov. 19, 2014, the same day he took his oath, Coffey filed an affidavit with Evans’ office which outlines what types of assignments judges are eligible for. Coffey stated that he was eligible for assignment as a senior judge throughout 2015.

“I have never represented myself as senior judge,” Coffey told me, adding that he is careful never to misrepresent himself in court. “I have taken judicial oaths every term since 1991 and after retirement in 2015. I filed the originals.”

His response does not explain why he listed his title as senior on multiple government forms, and Coffey never directly addressed any questions tied to the records I reviewed and forwarded to him.

“I believe I am legally qualified to sit in most any trial court under Texas law,” Coffey said. “You must realize that when you get out of populated areas, a single Texas judge may preside over family, probate, criminal, and all facets of civil [cases] in a week of dockets. Some multiple-county districts may do all types of law in several counties. Specialty jurisdictions are largely only in higher populations of cities.”

Coffey never presided over a family court case during his active career, meaning he does not meet state eligibility to be assigned to family court cases, but in 2015 and 2021 following retirement, he requested assignments to family court cases.

Whether or not Evans ever assigned Coffey to a family court case remains unclear because Evans, according to one confidential source (not Wright), is allegedly hiding Coffey’s past assignments. The source, who monitors judicial misconduct across the state, began inquiring into Coffey’s eligibility to serve on the bench following the Weekly’s publication of an editorial about the Wright case in February. The watchdog recently provided me with two emails from Evans’ office. In one, from late March, Evans said that Coffey’s assignments can be retrieved in return for $114.

“We have identified the documents, and they total 242 pages,” Evans wrote.

Evans changed his stance in an email he recently sent to Wright, saying that copies of Coffey’s past assignments do not exist. I have made my own request under Rule 12 — Texas courts’ version of open records requests — for copies of Coffey’s assignments but have not received the documents.

My other Rule 12 requests revealed that Coffey told one of Wright’s attorneys that he files oaths every year, although county records show otherwise. Visiting judges must file oaths on the first day of any trial they preside over. Depending on whether the trial is in a county or district court, the judge must file with either the county clerk or secretary of state’s office.

“We have checked our records and did not find any oaths responsive to your requests for oaths for Judge Daryl Coffey 2014 to present,” a Tarrant County clerk told me via email.

The secretary of state’s office similarly has no oaths by Coffey on file since 2014. Coffey said that he has filed the required constitutional oaths around a dozen times over his 24-year career. When asked about the lack of any oaths on file since 2014, Coffey referred me to the “presumption of regularity,” a phrase first used by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1926 that supports acts of public officers in the absence of clear evidence to the contrary, which I took to mean: “If Evans assigned me, it must have been OK.”

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals ruled in 1999 that a valid constitutional oath was required for a judge’s ruling to stand in the often-cited case Prieto Bail Bonds v. State.

In 1993, retired Judge Jerry Woodard of El Paso County ordered bondsmen with Prieto Bail Bonds to forgo $40,000 because a defendant who held a Prieto bond had failed to appear in court by the time Woodard called roll. Attorneys representing Prieto appealed the ruling to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. The 1999 decision by the nine justices overturned multiple lower court rulings and found that Woodard’s actions in 1993 were void because the retired judge had not taken the oath after retiring.

“Because Judge Woodard was required to take the constitutional oaths but did not do so, all judicial actions taken by him in the case below were void and a nullity, so were without authority,” the court’s opinion read.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals is equal in standing to the Supreme Court of Texas, meaning that Prieto Bail Bonds v. State carries the weight of the highest court in the Lone Star State.

In March, one of Wright’s appellate attorneys asked Evans for all constitutional oaths filed by Coffey since retiring.

“What I need quickly is any documentation related to his most recent oath of office that would cover the time frame of our client’s trial,” the attorney wrote in an email, referring to Wright’s court case.

Judge Evans’ office failed to disclose that there were no documents responsive to that request. Instead, an administrator with Evans’ office gave Wright’s attorney several affidavits used by Coffey to request assignments.

In the coming weeks, our news magazine will receive documents that may indicate when Coffey and other judges presided over cases without oaths and whether other judges are being assigned senior-judge cases erroneously. Coffey said that he is scheduled to fill in for Judge David Hagerman, who presides over the 297th District Court, in June — two weeks after the start of former police officer Aaron Dean’s murder trial, which Hagerman is assigned to. I have requested a copy of Coffey’s assignment to Hagerman’s court. It remains unclear whether or not Hagerman knowingly requested a constitutionally unqualified visiting judge to preside over the 297th District Court.

Following Coffey’s retirement in 2014, Judge Charles Vanover filled the vacated criminal court and has served there since. On his most recent campaign page, Vanover lists Coffey as a “retired senior judge” under the endorsements section. The State Commission on Judicial Conduct that enforces judicial ethics laws, based on the commission’s public statements, bars judges from endorsing candidates.

I reached out to Vanover to learn who provided that description of Coffey but did not hear back. Coffey said his name was used without his permission, and Vanover recently removed Coffey’s name from his 2022 campaign website.