In 1940, a volcano erupted in Fort Worth.

Let me repeat that.

In 1940, a volcano erupted in Fort Worth.

*****

In late October of that year, the gentle folk of Fort Worth began to register unpleasant rumblings. Faint at first, the tremors quickly grew more noticeable and less infrequent. Coffee pots in mansions rattled just a little, and there were barely perceptible trembles of picture frames in local society halls. But then the rumblings became a gossipy din. Soon the stately offices and brownstone porticos of the prodigally privileged were on full alert. And by the time the Nov. 10, 1940 edition of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram — with a review touching on the cataclysm — was retrieved by servants from the most luxurious lawns or by most of the rest of our forebears from modest lawns, everyone knew why.

Virulent rather than violent, the volcano was not an earthen aperture protruding dramatically from the prairie landscape. It was the explosive response that a book elicited from the River Crest Country Club set. Its eruption was more literary than lava-based, but it blew chunks of Cowtown society improprieties sky-high (for all to see) and was followed by a spew of vitriolic outrage by the masters of Fort Worth commerce.

Metaphorically speaking, however, their response would not resemble ancient Pompeii’s. Upon the manuscript’s release by The Dial Press on Nov. 8, 1940, the offended parties immediately summoned and exercised the kind of absolute dominion that only the deepest pockets in American capitalism enjoy. And they wielded their control in a way that today’s would-be and actual Lone Star political powerbrokers can only dream of.

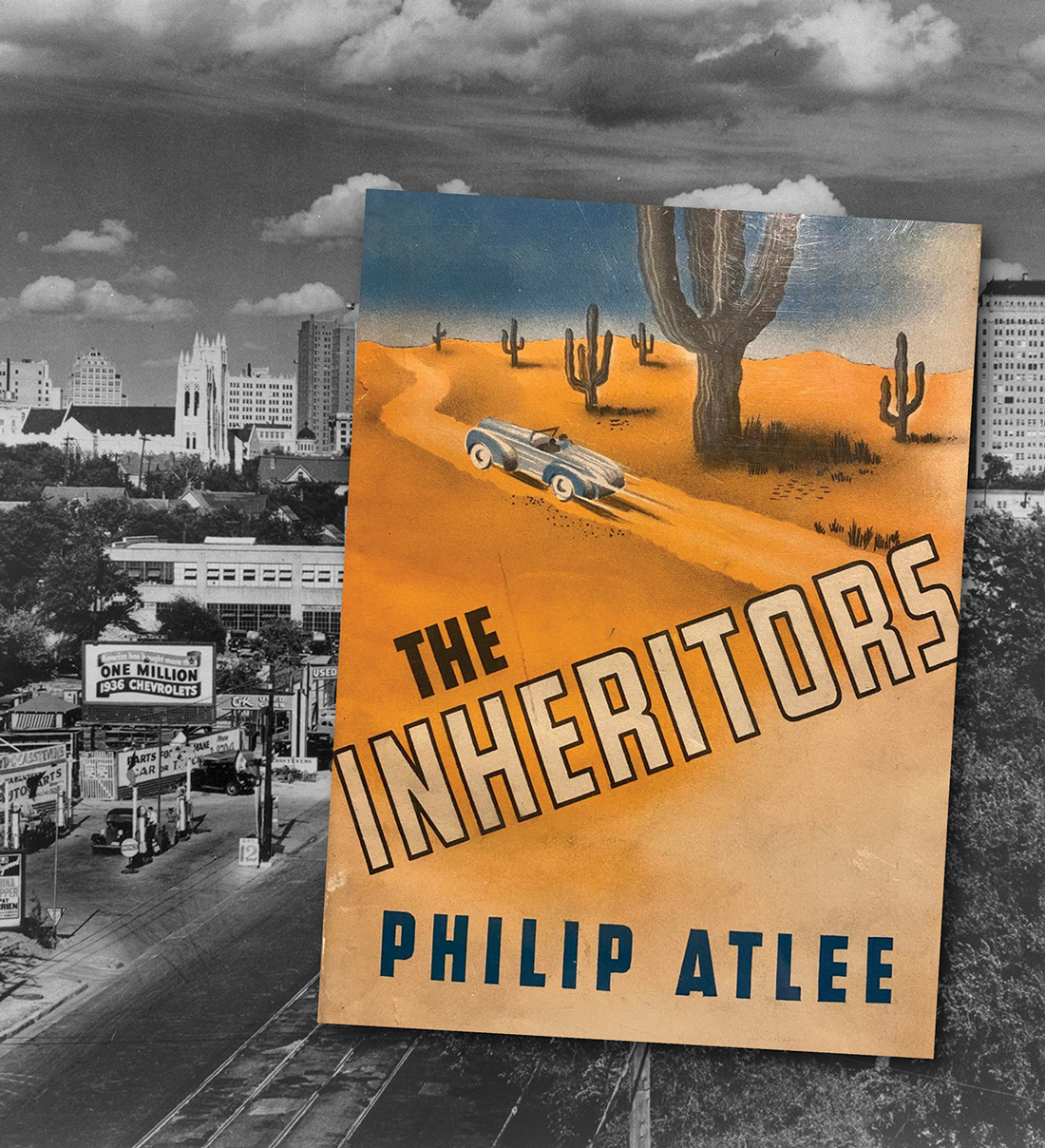

The seismic, literary roman a clef behind the pre-WWII convulsion in Fort Worth was The Inheritors, and it was written by Fort Worth native James Young Phillips under the pseudonym Philip Atlee. Peruse, if you will, parts of the introduction and try to gauge the general indignance Cowtown “elites” must have experienced.

This is no golden legend. Instead, it is a bare, transcripted tale of youth. A guy named Mumford spilled a little blood on the story, and all of us helped the action along, but there was no great bravery involved. It all happened in Fort Worth, Texas, but that was only an accident of narration. The story could have been told anywhere in America, about any place that had a country club. Let no one think that the group herein described was atypical of youth. We were only a fringe, but there were a few of us everywhere. Many of our contemporaries, in the middle thirties of the twentieth century, led admirably sane lives and had a brisk Y.M.C.A. outlook. These are the ones who will undoubtedly save the country when the going gets toughest, but, as Cavin Jarvis said, they were damned uninteresting. I suppose the formation of character is a tedious thing. …

The overlords of Fort Worth inhabited the quietest streets. Their large homes fringed the golf courses, and had three or four-car garages back of them. The interiors of these homes were lightened by pictures the owners did not understand or care to understand, and, in some cases, actually disliked. The wives of the owners were well tended and usually apprenticed to the intelligentsia. They were women who bought Shakespeare in handsomely bound volumes; they bought him and then had their maids dust him at regular intervals. The pages were usually uncut, but the owners were proud to have captured Shakespeare so that he could not get away. They trotted about, these women, to garden festivities and quick culture clubs, and they played bridge for rapaciously high stakes.

Their husbands did nothing but make money, but they could not be blamed for that. It was all they had been taught to do, and most of them were expert in the field. They were, for the most part, patient men who had been so strongly indoctrinated with the virus of the dollar aristocracy that they could not enjoy themselves fully even when they were financially able to do so. Therefore they were principally that sad sight, paunchy American business men floundering around, flailing ineptly at a white golf ball.

And set down in the heart of the town were the children of the country-club bludgeoners, the children who were being readied to catch the torch of Business. Not all of them were like us. We were well taught, but we were taught too much, and not of the right things. We drove fast cars and drank too much. The inference was given us, by well-bred curlings of the lip, that it was neither good nor desirable to be skilled in a trade. Instead, we were taught to prize the professions, which insisted on the profit motif in every conscious act of life. …

We were the inheritors in this last decade of the twentieth century. … We had no great respect for our elders, and we could smell, by some strange clairvoyance of despair, the neat destruction that was being built for us. …

At this ripping, dream-destroying junction of responsibility and awakening, we needed meaning as individuals. We needed it badly. … For lack of something to believe in, we came toward maturity as ill-met and unmannered pilgrims in a fog.

The first chapter begins with main character George Bellamy Jimble, III (based on Phillips himself) waking with a hangover, and sophomoric episodes of masculine debauchery promptly ensue. Phillips’ Jimble is a self-described “decadent Tom Sawyer,” and his real-life friend Roy Lawrence Harris — depicted in the book as “Cavin Jarvis” — qualified “as a chromium-plated Huck Finn.”

Courtesy the author

Phillips’ Jimble and Harris’ Jarvis are the two main characters of The Inheritors, and for the next 24 chapters, they drink, chase girls, pursue a questionable, easy-money grift for liquor money, express profoundly dim views of country club gaiety, and undermine the entire Cowtown “dollar aristocracy” with unexpectedly powerful jabs and bullseye quips.

After watching the attendees of an outdoor River Crest Country Club dinner, for example, Jimble silently observes that one very wealthy middle-aged couple nearby had little more to do then watch their fortune grow and that they “were very careful people and ate every bite of their salads,” Jarvis expands. “Can’t be happy,” he continues. “Too rich. Been rich too long, and they aren’t people anymore. Just deadheading along until they grow cold.” Then Jimble and Jarvis turn their attention to another wealthy couple. Jarvis delineates between the manicured twosomes. “Different. Entirely different. He’s just passing through his money like a thirsty man passing through a green country. He’s using it, making it buy him things. He knows there aint [sic] pockets in a shroud.”

“It could be,” Jimble answers. “Maybe they ought to lock the people up in the bank vaults and let the money do the living.”

Later, at the same gathering, Jimble and Jarvis’ commentary becomes more incisive. When an orchestra begins to play, Jimble takes in the ostentatious display and flatly asks, “What’s the good in it?” Jarvis stares at Jimble, his eyes smooth, “glazed by drinking” but unblinking. “The same song and the same singers,” Jarvis says. “We’re not people; we’re just a set of attitudes walking around with logic-locked approaches to everything in life, and thirty phrases locked up in back of our teeth.”

On another evening occasion as WWII approached, Jimble’s thoughts on a high balcony before inebriation once again holds sway, are eerily prescient. For his generation and generations to come.

I tried to convince myself that I should not get drunk at the hotel, that I should be at home ruining my eyes over ponderous tomes concerning The Really Important Things in Life. I tried to think of one thing I could have learned in four colleges that would be an index to avoid fear of getting drunk or fear of being killed in a war started outside my ken and not touching me in any way. … I tried to think of all my elders had taught me, and I tried to believe that some things were worth dying for, worth being gallant for, or even worth thinking of before sleep. But all my thoughts were flawed; they were all false rabbits and the hounds of belief would not run for them.

Jimble and Jarvis and the rest still keep up the proper appearances. “The group of us, locked behind paneled doors and brocade curtains in an eyrie over the streets of Fort Worth, was conscious of knowing how to react conventionally under given situations, and of being a scrubbed and presentable segment of country-club Christianity. We were all comforted by the unspoken realization, and so we talked earnestly, said nothing, and drank our drinks.”

And, in the end, the main characters — like Phillips’ description of “Mumford,” who “never lost his zest” and “was the nearest thing to a one man revolution” Jimble was “ever privileged to witness” — all futilely tilt their lances at “capitalist windmills.”

The book was a brilliant but scandalous marvel in its day, and those portrayed unflatteringly immediately forbade its presence and never forgot its author.

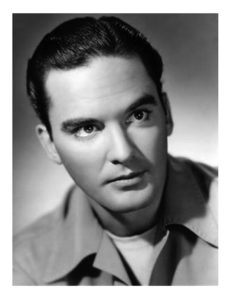

Harris, a.k.a. Cavin Jarvis, would show up in Hollywood and get on with Universal Studios shortly after The Inheritors itself was published after actually presenting a volume as part of his resumé. He would go on to act in 19 films under his given name but, after serving in WWII, performed under the name Riley Hill. He appeared in more than 70 Hollywood films altogether and had a steady run on TV classics like The Lone Ranger, Dick Tracy, The Gene Autry Show, and The Range Rider during the early 1950s. He played the apostle John in the 1952 series The Living Bible and spent the rest of the decade playing parts in The Roy Rogers Show, The Cisco Kid, Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok, The Adventures of Kit Carson, and Mackenzie’s Raiders.

In terms of success and future prospects, The Inheritors would do the opposite for Phillips. The book faced the wrath of Cowtown’s “dollar aristocracy” unbound. They bought up every copy they could find and no doubt dispatched threatening letters to Phillips’ publisher in New York, where Phillips was then living. The book, the volcanic eruption, and the volcano were snuffed out almost immediately, and Fort Worth went back to business as usual.

At the time, however, The Inheritors garnered no small amount of praise and accolades outside of Texas. The Dec. 1, 1940 edition of The Baltimore Sun called the book “unadorned and powerful and reminiscent of James Caine [author of The Postman Always Rings Twice (1936) and Double Indemnity (1936)] and the early Hemingway.” The Dec. 23, 1940 edition of The New Republic said the author “writes of the younger Country Club set around Fort Worth with a freshness and ease of a natural talent on the loose,” and the story “has the vitality and conviction of a scandal whispered in the cloakroom about the merrymakers you can glimpse in the ballroom beyond.” The Jan. 19, 1941 review in the Pittsburgh Press calls Phillips’ George Jimble “a rich man’s Studs Lonigan” and issues a warning: “There is danger of taking a book like this too seriously. There is a greater danger in not taking it seriously enough. … There’s some very fine writing to be found.”

Back in Fort Worth, however, The Inheritors was relegated to rash petulance and plebian bluster. The dismantling of the book’s import and legacy was practically already complete.

Before the book was released, the June 15, 1940 Kirkus review of the work was encouraging. “This is a book that will appeal to those who started on [F. Scott] Fitzgerald and followed through to [John] O’Hara [author of Appointment in Samarra and Butterfield 8], and who demand the best in that particular genre. It is even tougher than O’Hara; there’s some of Caine’s sadistic side; it is a full-blooded job, written in a virile, vital prose style which makes a terrific impact.”

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram’s Nov. 10, 1940 post-publication review of The Inheritors concedes Phillips’ obvious literary talent, but it concludes with a hardly coincidental — and probably obligatory — hatchet-job.

As a first novel by a somewhat immature and confused young man, bewildered by his own task, The Inheritors is a flaming story of a group of over-age adolescents afflicted by their overstimulated instincts, their amorality and a rather stupid, cruel inheritance not of their own making. … Any confidant of young Phillips knows he was deadly earnest, honest and even crusading when he wrote The Inheritors. Thereby, he fell innocently into the trap to ‘tell all.’ The novel suffers from an overextension of candor in several incidents that should have been saved for a privately-printed book of limited circulation. America, alas, is hardly mature enough for some of the scenes in The Inheritors, as artfully as they may have been described.

From the standpoint of literary merit, The Inheritors reveals a young author with a poetic sense which follows him into the gutter, an insatiable curiosity about life which amounts to obsession, and a rare knack for apt phrases and meaningful words. The Inheritors may be a product of a poet who cannot quite turn realist without being nasty about it.

Many contemporary Texas newspapers followed suit. The Feb. 23, 1941 Wichita Falls Times review of The Inheritors panned it “because of the filth it descends to in places.”

So, essentially, instead of noting this new, talented Fort Worth writer, Cowtown society dismissed him as a crank, disowned him, and literally attempted (and, for the most part, succeeded) in erasing him from annals of Fort Worth and Texas literary history. Meanwhile, other Fort Worthians began creating and circulating textual keys that identified the real-life characters portrayed in The Inheritors’ pages. Imagine if sales of the book had not been kneecapped. What status might it or its author have achieved in American letters?

The general public has a short memory and a limited attention span.

Fortunately, writers do not.

When George Sessions Perry — National Book Award-winning American novelist, World War II correspondent, and one of the highest paid magazine contributors of his time — put together Roundup Time: A Collection of Southwestern Writers in 1943, he included excerpts from the The Inheritors alongside those of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, Oliver La Farge’s Laughing Boy, and works by J. Frank Dobie, Katherine Anne Porter, O. Henry, Conrad Richter, and more. All names that appeared repeatedly in readers’ digests and American lit classes for decades to come.

Courtesy the author

Some advocates suggested The Inheritors was an adult version of The Catcher in the Rye a decade before J.D. Salinger’s adolescent classic written for adults, but The Inheritors was edgier and contained more heart and more honesty. A chapter near the end boldly and poignantly chronicles Jimble’s trip with a young society woman to San Antonio for an abortion. It was scandalous in its day — it would probably get them both sued or arrested today.

In 1981, A.C. Greene, a widely respected Texas journalist, fiction writer, historian, and book critic, published The Fifty Best Texas Books. The list included the usual suspects, including Coronado’s Children by J. Frank Dobie, Blessed McGill by Bud Shrake, Pale Horse, Pale Rider by Katherine Anne Porter, 13 Days to Glory: The Siege of the Alamo by Lon Tinkle, Hold Autumn in Your Hand by George Sessions Perry, Hound Dog Man by Old Yeller author Fred Gipson, and an unknown, lost classic that hardly anyone had ever heard of: The Inheritors by Philip Atlee. And Greene’s remarks are worth sharing.

This isn’t Cowtown. This is the young social set — carousing driving big cars too fast, going from party to country club to any kind of devilment and eventual crack-ups — physical and mental. It’s an overindulged generation. … The story is well done, and it was told thirty or forty years before its time. Few Texas books have been able to repeat the harsh dismay, the inspired brutality, of The Inheritors.

In The New Frontier: A Contemporary History of Fort Worth and Tarrant County (2006), Ty Cashion wrote that The Inheritors “rocked Fort Worth society a generation before Grace Metalious’ Peyton Place would cause the blue blood of New Englanders to run cold.”

In 2011, Texas author Bill Crider brought it up again, after grabbing The Naked Year, a renamed re-release of The Inheritors published in 1954. Crider called it “excellent writing” and “sort of a hardboiled Gatsby, set in Fort Worth.” Except Fitzgerald’s Gatsby buys into America’s “dollar aristocracy” completely, while Jimble and Jarvis express open contempt for it.

In 2019, one day after his death, the Big Bend Sentinel published much-beloved Texas historian and raconteur Lonn Taylor’s investigation into The Inheritors under the title “A Stealth Author from Fort Worth is Revealed” in his theretofore syndicated column, Rambling Boy. Taylor says his story was “two years in the making,” and it took him so long to finish it because he couldn’t find anyone who actually knew James Atlee Phillips.

A 1961 graduate of TCU and actually a former student of the TCU instructor The Inheritors was dedicated to, Lorraine Sherley (whom the Lorraine Sherley Professor of American Literature at TCU is named after), Lonn Taylor was a former historian and director of public programs for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Here in Texas, he helped curate exhibits for San Antonio’s HemisFair in 1968. In 1970, he became the director of the University of Texas’ Winedale Historical Complex. After that, he served as a curator for the Dallas Historical Society. In 1983, he also served as the guest curator of an exhibit celebrating the American Cowboy for the United States Library of Congress. Lonn Taylor was no lightweight — and even he couldn’t dig up much on Atlee. But hardly could anyone else. As Taylor notes in his piece, “Copies of The Inheritors are as scarce as hen’s teeth.”

One of the only known copies around was tucked away in the Fort Worth Central Library’s special collections. And, inside it, someone at some point wrote “Phillips, James Young” under the publisher-printed “Philip Atlee” on the volume’s frontispiece. If you look up the author of The Inheritors on Wikipedia, his name is listed as James Atlee Phillips. As Taylor himself noted, Phillips was a “stealth author.” This was a vast understatement.

*****

James Young Phillips — a.k.a. James Atlee Phillips, a.k.a. Philip Atlee — was born on Jan. 8, 1915, in Fort Worth. His father was a lawyer for members of the River Crest Country Club’s big oil families and made a handsome living. The Phillipses had a big house right off one of the greens of the River Crest Country Club golf course. Edwin Sr. was a member of the law firm of Phillips, Trammell, Chizum and Price. Edwin Sr. was a director of the Farmers and Mechanics National Bank before its merger with the Fort Worth National Bank. And Edwin Sr. served as the president of the prestigious Fort Worth Club. But in the late summer of 1928, he grew ill and, on Sept. 5, succumbed to pneumonia.

Edwin Sr.’s affairs were in order, and his wife, Mary Louise Phillips, and their children — Edwin Jr., James, Olcott, and David — seemed at first to be fairly well provided for, but a little over a year later, the 1929 stock market crash wiped out the family’s savings. Practically destitute, Mary sold what she could from their big house and went to work for the Fort Worth Independent School District. She and her sons were suddenly poor in a mansion in one of the wealthiest neighborhoods in the nation.

If you recognize Mary Louise Phillips’ name, it’s probably because there’s a FWISD elementary school named after her south of I-30 in on the West Side. She worked hard and distinguished herself, and she did the best she could for her boys. Atlee Marie Phillips, James Young Phillips’ grandniece, recently told me that in everything she heard about her granduncle, her granddad, and their brothers, she always sensed that they were profoundly affected by their sudden poverty in a neighborhood of such incredible wealth.

“It was really hard on them,” Atlee said. “They tried to keep up appearances, and it was extremely difficult. And then Jim writes this blistering commentary about all of these people.”

In a letter to his mother, who was a distant relative of Major Clement R. Attlee, lord privy seal and unofficial deputy prime minister of England at the time (and Winston Churchill’s chief adversary), Phillips shared his thoughts on The Inheritors (which he originally thought of calling “Threadbare Galahad”).

The characters are principally composite, but some situations are grounded on fact. I shall, in all possibility, create a tidy little corps of antagonists and it may even be that you will not like what I have done. But remember that I write no line, salacious, embittered or pornographic, that I didn’t write truly.

Mrs. Phillips, vacillating between pride in her son’s writing and sympathy for those his sizzling prose offended and those who might criticize or even attempt to ban it, wired him this message: “Everyone will be shocked and no wonder. But Philip Atlee has written the truth about the thank god-small segment of youth which he knew. He writes with a wallop and is going to be a writer.”

Or at least that was her son’s plan, and the reviews almost everywhere except home seemed to reinforce his intentions, but the influence of the “dollar aristocracy” he crossed had scope and reach and doused his early aspirations before he got very far.

Then WWII intervened.

Phillips joined up, and many reports suggest he advanced quickly, first training pilots at Hicks Airfield north of Fort Worth, then serving in Burma and other spots in Southeast Asia. Then he joined the Marine Corps and spent the last two years of WWII working as the associate editor of The Leatherneck, the Corps’ official magazine. While editing The Leatherneck, he was also getting fiction published in magazines like Collier’s, Argosy, and Blue Book. After the war, Phillips moved to San Miguel de Allende in Mexico and was able to live there comfortably selling a couple of stories a year. When he and his first wife, former model Joyce Clayton — whom he married in 1940 — divorced in 1949, Phillips returned to Burma. He worked for Amphibian Airways during the Burmese civil war and also had a stint at Cathay Pacific Airlines. Many assume Phillips was an intelligence operative during this period (if not before), but this claim has never been substantiated. His brother David, however, would become the head of C.I.A.’s Western Hemisphere Division, and many conspiracy theorists believe he was connected to the JFK assassination.

In 1952, Phillips relocated to the Canary Islands and, in 1954, ran into fellow Cowtown native John Graves, author of the Lone Star classic Goodbye to a River (1959) while residing on the main island of Tenerife. Later, in his book Myself and Strangers (2004), Graves wrote that Phillips’ frustration with the reception of The Inheritors had hardly waned. Phillips reportedly told Graves that he’d love “to buy a petty little atom bomb and at cocktail hour one afternoon he’d drop it down the chimney of the men’s bar at River Crest Country Club.”

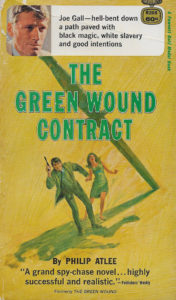

Phillips would go on to dabble in Hollywood, helping to salvage the screenplay for John Wayne’s 1952 film Big Jim McLain (which Phillips later called “simple anti-communist baloney”) and the 1958 film noir Thunder Road, starring Robert Mitchum. Phillips also wrote for projects involving Jane Russell, John Forsythe, and a young Stanley Kubrick. In 1963, he began writing the Joe Gall “Contract” series, the first book of which was The Green Wound (later changed to The Green Wound Contract) but also under the pen name Philip Atlee. The series would include 22 novels and win him an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America in 1970. But perhaps the most important line in the entire series was the first line in the second chapter of The Green Wound: “The story of my life is: ‘He rambled till they had to cut him down.’ ”

In 1984, the reclusive Phillips sat for an interview with Francis M. Nevins, an author of six mystery novels and, until recently, a professor at the St. Louis University School of Law. Nevins published the interview in his 2010 book Cornucopia of Crime: Memories and Summations. Phillips doesn’t say much about The Inheritors, but his fierce contrarian intelligence is on full display. The most telling exchange in the interview is initiated by Nevins, who tells Phillips what he liked most about his spy novel writing was the intriguing sense of moral and ethical schizophrenia — that unlike Ian Fleming’s James Bond books, Joe Gall isn’t always shilling for the “good” guys. Phillips’ response harks back to everything we should admire in him.

That’s because there was bifurcation in my own temperament. As a writer, I know that if you don’t have the bullshit to keep it moving from page to page, you’re going to lose readers. At the same time, I wasn’t willing to admit to being such an absolute dunce that I didn’t know it was bullshit in the first place. … Gall knew what he had to do but he knew that it was a lot of bullshit, too, and that he was on the wrong side.

Phillips eventually settled in Corpus Christi, where he died on June 2, 1991. His New York Times obituary referred to him as Philip Atlee, and most of the rest called him James Phillips or James Atlee Phillips. They all ignored Phillips’ middle name, which is unfortunate in its own right. The “Young” comes from his maternal grandparents, and his grandmother, Mrs. G.A. Young, known to friends and relatives as “Mother Young,” was active in the women’s suffrage movement and organized women in Houston during one of the first elections in which women were allowed to vote.

*****

The first mention of The Inheritors I encountered occurred about 10 years ago. I don’t remember the exact circumstances, but I made note of it. Then I got busy with other things. When I did finally double back, I — like Lonn Taylor — couldn’t find a copy. I just found a Judy Alter and James Ward Lee chapter on it in their 2002 book Literary Fort Worth, but the entire chapter was basically just Phillips’ take-no-prisoners introduction to The Inheritors — which I shared excerpts from early in this article. Eventually, I became aware of the copy available at the Fort Worth Central Library and made three trips there to start reading it. Then, again, I got busy with other projects. But The Inheritors struck a chord that never stopped reverberating. How could so few of us know about this book?

Class and wealth have always been a big thing in Fort Worth. My father, for example, grew up dirt poor on the south side of town, and he was not terribly welcome when he attended R.H. Paschal High School in the mid-1950s, when it was an institution for well-to-do and/or rich white kids. He and other students from low-income households were reminded of this fact often.

Courtesy the author

In the late summer of 1976, a plotline fit for The Inheritors played out in what is soon to be a new Stonegate real estate development just east of Hulen Street, south of I-30. An intruder entered the former Stonegate mansion of oil tycoon Cullen Davis — one of the inheritors of Hugh Roy Cullen, patriarch of one of biggest oil fortunes in American History. Davis’ former mansion (demolished in late 2021) was then inhabited by his second ex-wife, Priscilla Childers Davis, and the intruder killed her 12-year-old daughter, Andrea Childers, and Priscilla’s former TCU basketball star boyfriend, Stan Farr, and shot Priscilla herself. Priscilla staggered from the house being pursued by the killer just as family friends Beverly Bass and Gus Gavrel Jr. drove up the mansion driveway. The killer shot Gavrel, paralyzing him for life, after Bass identified Cullen Davis as the pursuer and called him by his name. Priscilla also identified Davis to police, saying he had shot her and Farr, disguised only by a wig. Police arrested Cullen Davis that night, at the house he shared with Karen Master, who would later become his third wife.

Davis, whose wealth was estimated at $100 million then, was tried for the murder of Andrea but, even with two eyewitnesses, found not guilty. The prosecutor, Tim Curry, was blunt. He said the prosecution was “out-bought and out-thought.” The trial of O.J. Simpson — who was not an inheritor — two decades later was a carnival sideshow compared to the Cullen Davis trial, because, at that time, Davis was considered to be the wealthiest American man ever to have stood trial for murder in the United States.

Later, in 1985, R.L. Paschal High — by then a little less affluent, a little less well-to-do, and a lot less white but still attended by children of the “dollar aristocracy” — produced the Legion of Doom, a group of prominent A-list academic, athletic, and inheritor-like white boys bent on enforcing their privilege and ridding their school of unwanted elements. They vandalized lockers and threatened classmates with guns. They built a homemade bazooka and a gasoline bomb. They denigrated poor kids and homosexuals, pipe-bombed a classmate’s car, and left a gutted cat splayed across another’s steering wheel. But after they were finally caught and charged, they got a slap on the wrist. And many of the families who were part of the local “dollar aristocracy” openly sympathized with these young men who — let’s be honest — ultimately committed acts of domestic terrorism.

A copy of The Inheritors popped up on eBay a year or so back, and I gladly overpaid for it. It wasn’t in great condition, but it was worth every penny. I read it immediately, and I was amazed and dumbstruck and immediately otherwise busy again. But the recent antics of Texas State Rep. Matt Krause and chairman of the Texas Legislature’s House General Investigating Committee — who is now running for Tarrant County District Attorney — made me pick The Inheritors up, again, and reread it.

Late last year, the Fort Worth Republican forwarded a now infamous letter to a Texas Education Agency official inquiring into 849 books in school libraries around the Lone Star state. The titles Krause focused on address topics ranging from race and racism and sex and sexuality to abortion and reproductive rights and LGBTQ rights. In the letter, Krause wanted to know how much was spent on these books, which allegedly include material “that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex.”

In terms of Republican politics, it was brilliant. GOP leaders are peerlessly adept at making political footballs out of anyone who isn’t white, male, and straight, but if you’ve lived in Fort Worth for a while and know about the “volcanic” eruption here in 1940, Krause looks more like a clumsy, bantamweight amateur than the true heavyweights of old. Because back in the day, if the big boys had a problem with a book, they didn’t wait for a local politician to do something about it. The big boys took care of it themselves. And they didn’t bother with political theatrics or publicity-grabbing threats or bans.

They simply made the offending text disappear.

*****

There is no question the “dollar aristocracy” has done some good in Fort Worth. And there’s no way Cowtown would be home to first-class, internationally renowned art museums, a world-class zoo, the Van Cliburn competition, Bass Performance Hall, Amon G. Carter Stadium, Dickies Arena, and more without our super-privileged overlords. But not everything they’ve done has been good any more than everything they achieved was earned, much less good or right.

On July 1, 1862, the U.S. Congress enacted a “duty or tax” with respect to certain “legacies or distributive shares arising from personal property” being passed down, either by will or intestacy, from deceased persons to their descendants or heirs. The modern American estate tax was enacted under Section 201 of the Revenue Act of 1916. Section 201 used the term “estate” tax, but by the 1940s — just after The Inheritors was published — opponents of the estate tax began calling it a “death tax.” In the 1990s, crafty Republican Newt Gingrich made hay out of this shrewd neologism, and now “inheritance tax” and “estate tax” are practically dirty words, and the fortunes passed down to the inheritor class aren’t really taxed at all. Today, inheritors aren’t just politically connected. Like George W. Bush or Donald Trump, they often go on to run their state or the entire country. Or like Paris Hilton (an heiress of a vast Texan hotelier fortune) or the Kardashian ladies (whose lawyer father or stepfather was one of O.J.’s lawyers), they can have their own TV shows or clothing lines and make millions or billions on top of what they have already inherited.

That line above from the Nov. 10, 1940 Star-Telegram lambasting of The Inheritors really sticks out now: “America, alas, is hardly mature enough for some of the scenes in The Inheritors, as artfully as they may have been described.”

Sadly, it seems just as true now as it was then.

This is America, not old Europe. We don’t have blue bloods. The dollar aristocracy is composed of capitalist green bloods, and if you peel back the red, white, and blue veneer of the United States, that’s what you see. Green. A smarmy green constantly fueled by greed. And whether or not our Cowtown overlords have generally done right or wrong by us in the bigger picture and broader timeline is certainly a subject worth debating, but we were all cheated and disinherited by the local dollar aristocracy’s sabotage and expurgation of The Inheritors and the potential literary legacy of James Young Phillips.

And our town and our citizenry remain the worse for it.

Out standing report

I am reminded of Betty Brinks summary: FTW is a pyramid and at the top are the few, the rest of us just work for them.