The legal hurdles are staggering. Even with new DNA results or other forms of compelling, exonerating evidence, Texas’ wrongfully convicted are at the mercy of district attorney offices and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals when filing claims of actual innocence. Denials are common, and only a handful of prisoners are exonerated each year in the Lone Star State.

Since 2006, the Innocence Project of Texas (IPTX) has worked to exonerate or free 25 innocent people who collectively served 341 years behind bars. IPTX executive director Mike Ware said his team sifts through around a thousand credible letters every year from incarcerated Texans seeking to overturn their convictions, either because they were wrongfully identified as the suspect or no crime occurred. An arson conviction for a fire not started by any person is a common example of a situation that results in bogus criminal charges.

The National Registry of Exonerations, which is considered the most accurate depository of such information, reports 3,035 exonerations since 1989. With nearly 400 cases since 1989, Texas is a leading state in the nation when it comes to wrongful conviction exonerations. Reporting by the Washington Post found that 54% of defendants were the victims of misconduct, either by police or prosecutors.

Last May, IPTX reversed the conviction of Lydell Grant, a Black man convicted of murdering a 28-year-old man in Houston in 2010. The day after the crime, a witness saw Grant and thought he resembled the knife-wielding murderer. The witness turned Grant’s vehicle information over to police, who subsequently arrested Grant. He was given a life sentence for first-degree murder in 2012 following a case that largely relied on shaky eyewitness testimony.

In 2015, Grant filed a motion seeking DNA testing of the evidence, and, three years later, IPTX took up the case. DNA testing found that Grant’s DNA was not present in DNA found at the crime scene. The new findings allowed Grant to be released on bond in late 2019. Soon after, police interrogated a man who confessed to committing the 2010 murder.

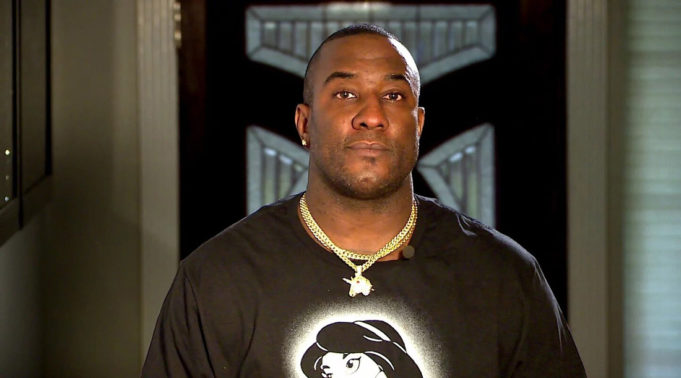

IPTX’s most recent effort to exonerate a wrongfully convicted Texan is being fought in Fort Worth. In December, a Tarrant County judge released Willie Thomas on bond — 10 years after he was sentenced to life in prison for murder. Thomas was falsely accused of murdering a local club owner in 2009, and IPTX’s investigation had found that Thomas’ DNA was not present on the murder weapon. Thomas’ trial partly relied on plea-bargain testimony from two men involved in the robbery. Though released, Thomas has not been exonerated, and his best hope for freedom will likely be a retrial that takes the new evidence into account.

Photo by Edward Brown

Ware said that, for every person who is released or exonerated, there are easily 10 incarcerated people equally deserving of having their convictions overturned. The long-time criminal defense attorney founded Texas’ first conviction integrity unit when he served as the Special Fields Bureau Chief for the Dallas County District Attorney’s office between 2007 and 2011.

I recently sat down with Ware at IPTX’s central office in downtown Fort Worth to discuss the work his nonprofit does and his views on Texas’ criminal justice system.

*****

Is the process of overturning convictions difficult by design?

The system was supposed to prevent wrongful convictions in the first place, but it hasn’t always worked out that way. There is not much in our history and tradition on what the process should be for dealing with a wrongful conviction. Other than the very general right of habeas corpus, there is nothing specifically in the Constitution that says someone who has been wrongfully convicted has a right to be exonerated. The Supreme Court has had many opportunities to say that it is a violation of due process for an innocent person to be convicted, incarcerated, and even executed, but they are yet to recognize that as a due process violation. Texas does recognize that actual innocence is a cognizable claim for relief in the Texas courts. We hope that the U.S. Supreme Court will catch up on the national and federal levels.

Has the general public become more sympathetic to the plight of innocent prisoners?

I think so. There has also been a backlash. There is an element of judges and DAs that lash out and push back on what they perceive as bleeding heart liberals telling them what to do. That’s not how we see ourselves. We see ourselves as pursuers of justice. Our efforts often find the true perpetrator. Through DNA and our investigation, we found the actual murderer in the Lydell Grant case, who confessed and is now under indictment largely because of our efforts. That’s good, and part of our work that judges and prosecutors do not normally associate with our organization. Those truly concerned with public safety will support what we do rather than attempt to undermine and discredit it.

What are the top reasons people are wrongfully convicted?

I think the reasons are common throughout the country. You can make that question as simple or complicated as you want. Poverty, racism, inequity are certainly the reasons. Another is that we convict so many people. That’s our solution to everything — criminalize it and convict them. If you convict a large number of people, a proportionally large number of them are going to be innocent.

A reason most people will point to because it’s easy to wrap your mind around is mistaken eyewitness identification, and there is some truth to that. Many wrongful convictions involved an eyewitness who inaccurately pointed to a defense table and said, ‘That’s the person who did it.’ That’s very unreliable testimony, but it is very convincing testimony to a jury. A major cause of inaccurate eyewitness testimony, aside from the infirmities of human perception and memory, is the fact that it’s coached. The police and the prosecutors know what they need that person to say to get a conviction, so they tell them what to say, and most witnesses will adhere to what the “authorities” tell them to do, even if they believe it to be wrong.

What role does police and prosecutor misconduct play in wrongful convictions?

It’s hard to say because, by its very nature, police and prosecutorial misconduct occurs in the dark and is not necessarily well documented when it occurs. There are so many things that are police and prosecutor misconduct but are disguised as something else. Mistaken eyewitness identification is one of those things. These mistakes are usually the result of coaching, the product of the police telling the witness who to pick in a photo spread as opposed to that witness making an honest mistake. It is misconduct with plausible deniability. When it turns out that the wrong person was convicted, the police blame the witness or victim.

Under Supreme Court-sanctioned law, police are allowed to lie, and they will shamelessly lie during interrogations. This can produce false confessions which law enforcement will latch onto as legitimate confessions. They will tell them that their wife said they are guilty when she didn’t. They’ll say, ‘If you will just confess and tell us what happened, we’ll make sure the DA will go easy on you. Otherwise, you will get the death sentence.’ That’s a complete lie, but it doesn’t matter. The jury generally doesn’t care that that’s what precipitated a confession. Once the false confession is out, [defendants] are often coerced into taking a plea deal in spite of knowing their own innocence. DNA exonerations alone show that false confessions are a common cause of wrongful convictions.

Does Tarrant county need a public defender’s office?

Every public defender’s office that I’ve seen has been good at what they do. I think the best ones are statewide as opposed to being run at the county level. That way they are not beholden to county politics. I think there are excellent attorneys in Tarrant County who take court appointments. I think the whole trope that court-appointed attorneys are bad is just bullshit. I think some of the best attorneys I’ve known were court-appointed, and some of the worst were hired. There are good attorneys and bad attorneys. No matter how much you pay a bad attorney, it’s not going to turn him or her into a good attorney.

What role do jailhouse informants play in false convictions?

This phenomenon of ‘jailhouse informants,’ more accurately characterized as ‘misinformants,’ is an institution that has been going on since at least the 1700s. That’s where somebody in the same jail as the defendant says, ‘While the defendant and I were up in the jail, he said he committed the crime.’ The jailhouse informant will often contact the police or the DA’s office and say, ‘Will you drop my case if I help you get this guy.’ If the prosecutors have a weak case, which could be an indication that the person is innocent, they may think that they need that testimony. They will reduce the sentence of the misinformant, or they may even dismiss that misinformant’s case outright. They can even pay the misinformant money to come into court to testify. Any idiot can come down from jail and be incentivized to lie, and studies show that juries tend to believe them.

They think it’s valid testimony if the judge allows it, but chances are the conversation never even happened and the testimony proffered by the prosecution and believed by the jury is a total lie. After rigorous and concerted efforts by The Innocence Project of Texas and the Tim Cole Commission, the state legislature has passed laws in 2017 regulating requiring county and district attorney offices to maintain a database of jailhouse informants and allowing attorneys to tell juries about their criminal history.

Photo by Edward Brown

Are prosecutors incentivized to have a high percentage of convictions?

That expectation was much more formal when I first started practicing law. I think so much has been made of wrongful convictions and the damage they cause that, although there is certainly pressure and incentive to get convictions, it’s not stated publicly anymore that that’s what is required to advance a prosecutor’s career. Prosecuting cases is a competitive endeavor, and there are winners and losers. If a prosecutor is perceived as a loser, he or she is not going to go anywhere in that office. The only real quantifier for winners and losers is who wins. With prosecutors, it’s, ‘Did you get a conviction? How harsh of a sentence did you get?’

Innocent defendants often rely on alibi witness testimony. Is that effective?

If you have been misidentified, most of the time you have an alibi defense. You can’t tell them anything about the crime because you weren’t there and you don’t know anything about it. In Lydell Grant’s case, he wasn’t at the scene when the murder he was convicted of occurred. He was somewhere else and didn’t even know that a murder had taken place. He did not know the victim or the murderer. He put on an alibi witness who was very credible, but the jury ignored it. The prosecutor treats [the alibi witness] like they are a liar. Even the judge often treats them like they are a liar, too, and juries pick up on that. Alibi witnesses are not professional witnesses, whereas cops are trained in how to testify. They are taught how to look like they are telling the truth even when they are lying. If someone is an alibi witness when their friend or family member is on trial, they tend to act very nervous in front of a jury. They are amateurs unfamiliar with the judicial process, and prosecutors often exploit this to their advantage.

How does the allocation of resources between prosecutors and attorneys affect criminal cases?

Resources are heavily weighted in favor of prosecutors. They have all of the institutions in their favor. An assistant DA has basically in-house cops who are part of the DA’s office. They can have people arrested, searched, and interrogated. They have entire investigative agencies like local police working with them. They have unlimited access to government-funded forensic labs. On the other hand, if I want something investigated, I can’t call up any police department or agency of any kind and say, ‘Can you arrest this guy and bring him to me?’ I can’t call up the Fort Worth Police Department forensic lab and tell them what tests to run or instruct them on what I need from them.

Why are ethnic minorities more likely to be convicted?

It’s not just limited to minority populations, although they do suffer the overwhelming brunt of this. Any marginalized citizen can be easily targeted by the criminal justice system. For one, there is pressure on police to make arrests. They are rewarded in their evaluations for the number of arrests they make. Prosecutors are, if not directly, indirectly rewarded for their convictions. Members of a minority population and other marginalized citizens often have less access to financial or political resources which can insulate someone from a wrongful accusation. They often don’t have powerful friends or family members on city council or within the police department. That makes a big difference in ways that you never find out about. If someone is from a prominent family, the police know not to pick on that person. If someone is going to arrest that person, they’d better be damn sure that they are guilty. On the other hand, there are usually no ramifications for targeting minorities or the otherwise marginalized. When they lack the resources to fight the full force of law enforcement throughout the grueling judicial process, they are often intimidated into taking deals even if they are innocent.

Do DAs take adequate steps to review cases?

Every office is different. Some are shameful, and I could name several, but some are also very good. It just depends on the elected leadership and culture of a particular DA’s office.

Is it a conflict to expect DAs to overturn their own convictions?

It shouldn’t be, but, as a personal matter, it is. They have often mouthed off so much about a conviction and raked in so much political capital from it before it turns out that they were dead wrong and sent an innocent person to prison while the real perpetrator got off scot-free, but whatever face they may want to save, a prosecutor’s job description can be reduced to ‘seeking justice,’ so the conflict is far greater in not overturning their own wrongful convictions. I can tell you that as we speak, a committee of the Texas State Bar is considering amending the State Bar ethical rules to require prosecutors who discover a wrongful conviction to take some modicum of action to correct it. The Texas District and County Attorneys Association is vocally opposing the proposed reforms.

What motivates you to continue doing this work?

The successes. It’s not like we have one every day, but when we do have one, it is wonderful for everybody. That keeps me going. When exonerated prisoners are released, so many of them are overwhelmed and mostly in a good way. Fortunately, Mr. Thomas has a strong family. Some people are released, and they don’t have that kind of support. There’s always an aspect of them wanting to enjoy some simple pleasure, like eating a steak or hamburger or learning how to use a cell phone. What really stands out in my experience has been noticing their serene appreciation of the freedom most of us take for granted. It’s profound in its simplicity, yet it is overarchingly important.

*****

Courtesy of IPTX

New proposals currently before the State Bar of Texas’ Committee on Disciplinary Rules and Referenda, the nine-member panel that proposes disciplinary rules for attorneys, if adopted, would compel prosecutors to disclose evidence that proves a person was wrongfully convicted.

The amendment to the Special Responsibilities of a Prosecutor of the state bar association would require prosecutors to forward evidence of a wrongful conviction to an appropriate county and the defendant. The new rule would compel prosecutors to take reasonable steps to investigate the wrongful conviction.

Ware recently wrote an op-ed for the Houston Chronicle that listed the reasons why he supported the measures.

“Mistakes in the criminal justice system happen,” he writes. “Advances in the science of forensic DNA testing alone have proven that these mistakes have imprisoned thousands of innocent people. Since 1989, 2,933 innocent people have been exonerated. Prosecutors should be part of the solution. Instead, they are effectively denying the existence of an undeniable problem. Prosecutors are by far the most powerful officials in the American criminal justice system. Prosecutors have at their disposal entire investigative agencies with the power to search and arrest. They have absolute discretion on whether to charge a citizen with a criminal offense, who to charge, and what level of offense to charge. Their charging power, combined with their plea-bargaining power, often predetermines the outcome of criminal cases. This broad discretion in their everyday decisions has profound effects on the lives of the literally hundreds of thousands of people who, sometimes through no fault of their own, become involved with the criminal justice system.”

The guidelines, Ware told me, have been model rules at the American Bar Association since 2012.

“When I started the first-ever conviction integrity unit in Texas, we were following those rules,” he said. “We exonerated 25 men in the four years I was there. They were not the rules we were required to follow, but it fell under the umbrella of seeking justice. I think we would see more [wrongful convictions overturned] if these rules were made part of the rules for prosecutors.”

And it is not just capital murder cases. The prosecutors have a quota.