Each year during Sunshine Week (March 13-19), a national campaign in support of open records and open government, The Foilies serve up tongue-in-cheek “awards” for government agencies and assorted institutions that stand in the way of access to information. The Electronic Frontier Foundation and MuckRock combine forces to collect horror stories about requests under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and similar state laws from journalists and transparency advocates across the United States and beyond. Our goal is to identify the most surreal document redactions, the most aggravating copy fees, the most outrageous retaliation attempts, and many other ridicule-worthy attacks on the public’s right to know.

And every year since 2015, as we’re about to crown these dubious winners, something new comes to light that makes us consider stopping the presses.

As we were writing up this year’s faux awards, news broke that officials from the National Archives and Records Administration had to lug away boxes upon boxes of White House documents from Mar-a-Lago, former president Donald Trump’s private resort. At best, stealing away with government records was an inappropriate move; at worst, a potential violation of laws governing the retention of presidential documents and the handling of classified materials. And while Politico had reported that when Trump was still in the White House, he liked to tear up documents, we also learned from New York Times writer Maggie Haberman’s new book that White House staff claimed to find toilets clogged up with paper scraps, which were potentially torn-up government records. Trump has dismissed the allegations, of course.

This was all too deliciously ironic considering how much Trump had raged about Hillary Clinton’s practice of storing State Department communications on a private server. Is storing potentially classified correspondence on a personal email system any worse than hoarding top-secret documents at a golf club? Is “acid washing” records, as Trump accused Clinton, any less farcical than flushing them down the john?

Ultimately, we decided not to give Trump his seventh Foilie. Technically he isn’t eligible. His presidential records won’t be subject to FOIA until he’s been out of office for five years. (Releasing classified records could take years, or decades, if ever.)

Instead, we’re sticking with our original 16 winners, from federal agencies to small-town police departments to a couple of corporations, who are all shameworthy in their own rights and, at least metaphorically, have no problem tossing government transparency in the crapper.

The C.R.E.A.M. (Crap Redactions Everywhere Around Me) Award — U.S. Marshals

The Wu-Tang Clan ain’t nothing to F’ with … unless the F stands for FOIA.

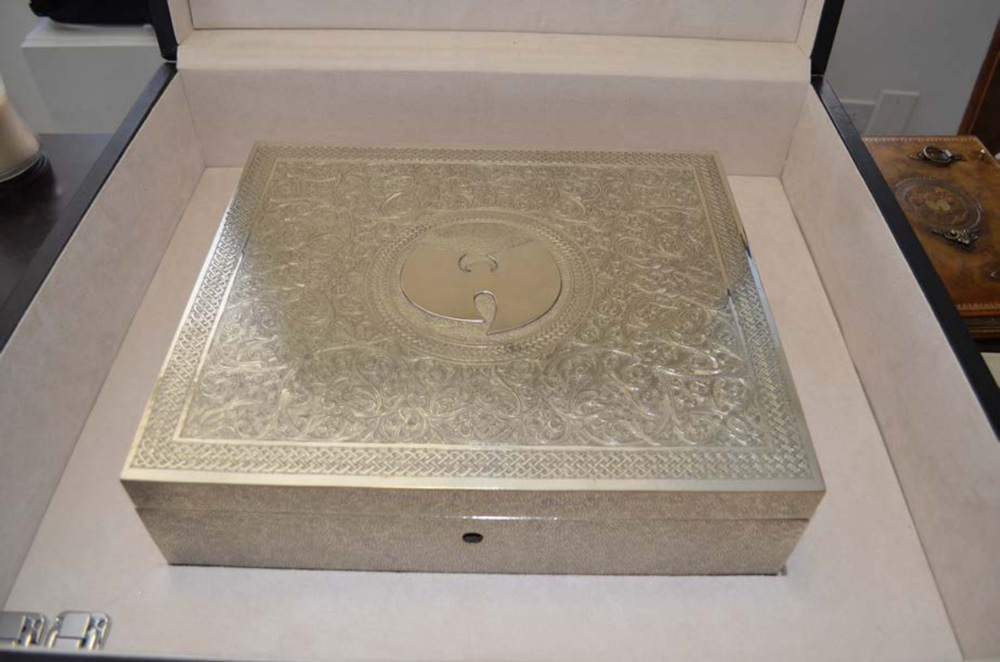

Back in 2015, Wu-Tang Clan put out Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, but they produced only one copy and sold it to the highest bidder: pharma-bro Martin Shkreli, who was later convicted of securities fraud.

Courtesy Jason Leopold, BuzzFeed News

When the U.S. Marshals seized Shkreli’s copy of the record under asset forfeiture rules, the Twitterverse debated whether you could use FOIA to obtain the super-secretive album. Unfortunately, FOIA does not work that way. However, BuzzFeed News reporter Jason Leopold was able to use the law to obtain documents about the album when it was auctioned off through the asset forfeiture process. For example, he acquired photos of the album, the bill of sale, and the purchase agreement.

But the marshals redacted the pictures of the CDs, the song titles, and the lyric book citing FOIA’s trade secrets exemption. Worst of all, they also refused to divulge the purchase price — even though we’re talking about public money. And so here we are, bringing da motherfoia-ing ruckus.

(The New York Times would later reveal that PleasrDAO, a collective that collects digital NFT art, paid $4 million for the record.)

Wu-Tang’s original terms for selling the album reportedly contained a clause that required the buyer to return all rights in the event that Bill Murray successfully pulled off a heist of the record. We can only daydream about how the marshals would have responded if Dr. Peter Venkman himself refiled Leopold’s request.

The Operation Slug Speed Award — U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

The federal government’s lightning-fast timeline (by bureaucratic standards) to authorize Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine lived up to its Operation Warp Speed name, but the FDA gave anything but the same treatment to a FOIA request seeking data about that authorization process.

Fifty-five years — that’s how long the FDA said it would take to process and release the data it used to authorize the vaccine, responding to a lawsuit by doctors and health scientists. And yet, the FDA needed only months to review the data the first time and confirm that the vaccine was safe for the public.

The estimate was all the more galling because the requesters want to use the documents to help persuade skeptics that the vaccine is safe and effective, a time-sensitive goal as we head into the third year of the pandemic.

Thankfully, the court hearing the FOIA suit nixed the FDA’s snail’s-pace plan to review just 500 pages of documents a month. In February, the court ordered the FDA to review 10,000 pages for the next few months and ultimately between 50,000-80,000 through the rest of the year.

These 10-day Deadlines Go to 11 Award — Assorted Massachusetts Agencies

Most records requesters know that despite nearly every transparency law imposing response deadlines, the responding agencies almost always violate those dates, yet Massachusetts officials’ time-warping violations of the state’s 10-business-day deadline take this public-records reality to absurd new levels.

DigBoston’s Maya Shaffer detailed how officials are giving themselves at least one extra business day to respond to requests while still claiming to meet the law’s deadline. In a mind-numbing exchange, an official said that the agency considers any request sent after 5 p.m. to have technically been received on the next business day. And because the law doesn’t require agencies to respond until 10 business days after they’ve received the request, this has in effect given the agency two extra days to respond. So, if a request is sent after 5 p.m. on a Monday, the agency counts Tuesday as the day it received the request, meaning the 10-day clock doesn’t start until Wednesday

The theory is reminiscent of the Spinal Tap scene in which guitarist Nigel Tufnel shows off the band’s “special” amplifiers that go “one louder” to 11, rather than maxing out at 10 like every other amp. When asked why Spinal Tap doesn’t just make the level 10 on its amps louder, Tufnel stares blankly before repeating, “These go to 11.”

Although the absurdity of Tufnel’s response is comedic gold, Massachusetts officials’ attempt to make their 10-day deadline go to 11 is contemptuous and also likely violates laws of the state and those of space and time.

The Return to Sender Award — Virginia Del. Paul Krizek

There are lawmakers who find problems in transparency laws and advocate for improving the public’s right to know. Then there’s Paul Krizek.

The Virginia lawmaker introduced a bill earlier this year that would require all public records requests to be sent via certified mail, saying that he “saw a problem that needed fixing,” according to the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

The supposed problem? A records request emailed to Krizek got caught in his spam filter, and he was nervous that he missed the response deadline. That never happened. The requester sent another email that Krizek saw, and he responded in time.

Anyone else might view that as a public records (and technology) success story: The ability to email requests and quickly follow up on them proves that the law works. Not Krizek. He decided that his personal spam filter hiccup should require every requester in Virginia to venture to a post office and pay at least $3.75 to make their request.

Transparency advocates quickly panned the bill, and a legislative committee voted in late January to strike it from the docket. Hopefully, the bill stays dead and Krizek starts working on legislation that will actually help requesters in Virginia.

The Spying on Requesters Award — FBI

If government surveillance of ordinary people is chilling, spying on the public watchdogs of that very same surveillance is downright hostile. Between 1989 and at least 2004, the FBI kept regular tabs on the National Security Archive, a domestic nonprofit that investigates and archives information on, you guessed it, national security operations. The Cato Institute obtained records showing that the FBI used electronic and physical surveillance, possibly including wiretaps and “mail covers,” meaning the U.S. Postal Service recorded the information on the outside of envelopes sent to or from the Archive.

In a secret 1989 cable, then-FBI Director William Sessions specifically called out the Archive’s “tenacity” in using FOIA. Sessions specifically fretted over former Department of Justice Attorney Quinan J. Shea and former Washington Post reporter Scott Armstrong’s leading roles at the Archive, as both were major transparency advocates.

Of course, these records that Cato obtained through its own FOIA request were themselves heavily redacted. And this comes after the FBI withheld information about these records from the Archive when it requested them back in 2006. Which makes you wonder: How do we watchdog the spy who is secretly spying on the watchdog?

The Futile Secrecy Award — Concord Police Department

When reporters from the Concord Monitor in 2019 noticed a vague $5,100 line item in the Concord Police Department’s proposed budget for “covert secret communications,” they did what any good watchdog would do — they started asking questions. What was the technology? Who was the vendor? And they filed public records requests under New Hampshire’s Right to Know Law.

In response, Concord police provided a license agreement and a privacy policy, but the documents were so redacted, the reporters still couldn’t tell what the tech was and what company was receiving tax dollars for it. Police claimed releasing the information would put investigations and people’s lives at risk. With the help of the ACLU of New Hampshire, the Monitor sued, but Concord police fought it for two years all the way to the New Hampshire Supreme Court. The police were allowed to brief the trial court behind closed doors, without the ACLU lawyers present, and ultimately the state supreme court ruled most of the information would remain secret, but when the Monitor reached out to EFF for comment, EFF took another look at the redacted documents. In under three minutes, our researchers were able to use a simple Google search to match the redacted privacy policy to Callyo, a Motorola Solutions product that facilitates confidential phone communications.

Hundreds of agencies nationwide have in fact included the company’s name in their public spending ledgers, according to the procurement research tool GovSpend. The City of Seattle even issued a public privacy impact assessment regarding its police department’s use of the technology, which noted that “Without appropriate safeguards, this raises significant privacy concerns.” Armed with this new information, the Monitor called Concord Police Chief Brad Osgood to confirm what we learned. He doubled down: “I’m not going to tell you whether that’s the product.”

The Highest Fee Estimate Award — Pasco County Sheriff’s Office

In September 2020, the Tampa Bay Times revealed in a multipart series that the Pasco County Sheriff’s Office was using “Intelligence-led Policing” (ILP). This program took into consideration a bunch of data gathered from various local government agencies, including school records, to determine if a person was likely to commit a crime in the future — and then deputies would randomly drop by their house regularly to harass them.

Out of suspicion that the sheriff’s office might be leasing the formula for this program to other departments, EFF filed a public records request asking for any contact mentioning ILP in emails specifically sent to and from other police departments. The sheriff responded with an unexpectedly high-cost estimate for producing the records. Claiming there was no way at all to clarify or narrow the broad request, they projected that it would take 82,738 hours to review the 4,964,278 responsive emails — generating a cost of $1.158 million for the public records requester, the equivalent of a 3,000-square-foot seaside home with its own private dock in New Port Richey.

The Rip Van Winkle Award — FBI

Last year, Bruce Alpert received records from a 12-year-old FOIA request that he filed as a reporter for the Times-Picayune in New Orleans. Back when he filed the request, the corruption case of U.S. Rep. William Jefferson, D-New Orleans, was still hot — despite the $90,000 in cash found in Jefferson’s cold freezer.

In 2009, Alpert requested documents from the FBI on the sensational investigation of Jefferson, which began in 2005. In the summer of that year, FBI agents searched Jefferson’s Washington home and, according to a story published at the time, discovered foil-wrapped stacks of cash “between boxes of Boca burgers and Pillsbury pie crust in his Capitol Hill townhouse.” Jefferson was indicted on 16 federal counts, including bribery, racketeering, conspiracy, and money laundering, leading back to a multimillion-dollar telecommunications deal with high-ranking officials in Nigeria, Ghana, and Cameroon.

By the time Alpert received the 83 pages he requested on the FBI’s investigation into Jefferson, Alpert himself was retired and Jefferson had been released from prison. Still, the documents did reveal a new fact about the day of the freezer raid: Another raid was planned for that same day but at Jefferson’s congressional office. This raid was called off after an FBI official, unnamed in the documents, warned that while the raid was technically constitutional, it could have “dire” consequences if it appeared to threaten the independence of Congress.

In a staff editorial about the extreme delay, The Advocate (which acquired the Times-Picayune in 2019) quoted Anna Diakun, a staff attorney with the Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University: “The Freedom of Information Act is broken.” We suppose it’s better late than never, but never late is even better.

The FOIA Gaslighter of the Year Award — Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry

In another case involving the Times-Picayune, the FOIA Gaslighter of the Year Award goes to Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry for suing reporter Andrea Gallo after she requested documents related to the investigation into (and seeming lack of action on) sexual harassment complaints in Landry’s office.

A few days later, following public criticism, Landry then tweeted that the lawsuit was not actually a lawsuit against Gallo per se but legal action “simply asking the Court to check our decision” on rejecting her records request.

Gallo filed the original request for complaints against Pat Magee, a top aide to Landry, after hearing rumblings that Magee had been placed on administrative leave. The first response to Gallo’s request was that Magee was under investigation and the office couldn’t fulfill the request until that investigation had concluded. A month later, Gallo called the office to ask for Magee and was patched through to his secretary, who said that Magee had just stepped out for lunch but would be back shortly.

Knowing that Magee was back in the office and the investigation likely concluded, Gallo started pushing harder for the records. Then, late on a Friday when Gallo was on deadline for another story, she received an email from the AG’s office about a lawsuit naming her as the defendant.

A month later, a Baton Rouge judge ruled in favor of Gallo and ordered Landry to release the records on Magee. Shortly after Gallo received those documents, another former employee of the AG’s office filed a complaint against Magee, resulting in his resignation.

The Redacting Information That’s Already Public Award — Humboldt-area Law Enforcement

Across the country, police departments are notorious for withholding information from the public. Some agencies take months to release body camera footage after a shooting death or might withhold databases of officer misconduct. California’s state legislature pushed back against this trend in 2018 with a new law that specifically puts officer use-of-force incidents and other acts of dishonesty under the purview of the California Public Records Act.

But even after this law was passed, one Northern California sheriff’s office was hesitant to release information to journalists — so hesitant that it redacted information that had already been made public. After local paper the North Coast Journal filed a request with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office under the 2018 law, the sheriff took two full years to provide the requested records.

Why the long delay? One possible reason: The agency went to the trouble of redacting information from old press releases — releases that, by definition, were already public.

For example, the sheriff’s office redacted the name of a suspect who allegedly shot a sheriff’s deputy and was arrested for attempting to kill a police officer in May 2014, including blacking out the name from a press release the agency had already released that included the name. And it’s not like the press had accidentally missed the name the first time: reporter Thadeus Greenson had published the release in the North Coast Journal right after it came out.

That isn’t Greenson’s only example of law enforcement redacting already public information. In response to another public records request, the Eureka Police Department included a series of news clippings, including one of Greenson’s own articles, again with names redacted.

The Clear Bully Award — Clearview AI

Clearview AI is the “company that might end privacy as we know,” claimed The New York Times when it publicly exposed the small company in January 2020.

Clearview had built a face recognition app on a database of more than 3 billion personal images, and the tech startup had quietly found customers in police departments around the country. Soon after the initial reports, the legality of Clearview’s app and its collection of images was taken to court. (EFF has filed friend-of-the-court briefs in support of those privacy lawsuits.)

Clearview’s existence was initially revealed via public records requests filed by Open the Government and MuckRock. In September 2021, as it faced still-ongoing litigation in Illinois, Clearview made an unusual and worrying move against transparency and journalism: It served subpoenas on OTG, its researcher Freddy Martinez, and Chicago-based Lucy Parsons Labs (none of which are involved in the lawsuit).

The subpoenas requested internal communications with journalists about Clearview and its leaders and any information that had been discovered via records requests about the company.

Government accountability advocates saw it as retaliation against the researchers and journalists who exposed Clearview. The subpoena also was a chilling threat to journalists and others looking to lawfully use public records to learn about public partnerships with private entities. What’s more, in this situation, all that had been uncovered had already been made public online more than a year earlier.

Fortunately, following reporting by Politico, Clearview, citing “further reflection about the scope of the subpoenas” and a “strong view of freedom of the press,” decided to withdraw the subpoenas. We guess you could say the face recognition company recognized their error and did an about-face.

Whose Car Is It Anyway? Award — Waymo

Are those new self-driving cars you see on the road safe? Do you and your fellow pedestrians and drivers have the right to know about their previous accidents and how they handle tight turns and steep hills on the road?

Waymo, owned by Google parent Alphabet Inc. and operator of an autonomous taxi fleet in San Francisco, answers, respectively: none of your business and no! A California trial court ruled in late February that Waymo is allowed to keep this information secret.

Waymo sued the California Department of Motor Vehicles to stop it from releasing unredacted records requested by an anonymous person under the California Public Records Act. The records include Waymo’s application to put its self-driving cars on the road and answers to the DMV’s follow-up questions. The DMV outsourced the redactions to Waymo, and Waymo, claiming that it needed to protect its trade secrets, sent the records back with black bars over most of its answers and even many of the DMV’s questions.

Waymo doesn’t want the public to know which streets its cars operate on, how the cars safely park when picking up and dropping off passengers, and when the cars require trained human drivers to intervene. Waymo even redacted which of its two models — a Jaguar and a Chrysler — will be deployed on California streets … even though someone on those streets can see that for themselves.

#WNTDWPREA (The What Not to Do with Public Records Ever Award) — Anchorage Police Department

“What Not to Do Wednesday,” a social media series from the Anchorage Police Department, had been an attempt to provide lighthearted lessons for avoiding arrest. The weekly shaming session regularly featured seemingly real situations requiring a police response. Last February, though, the agency became its own cautionary tale when one particularly controversial post prompted community criticism and records requests, which APD declined to fulfill.

As described in a pre-Valentine’s Day #WNTDW post, officers responded to a call about a physical altercation between two “lovebirds.” The post claimed APD officers told the two to “be nice” and go on their way, but instead the situation escalated: “We ended up in one big pile on the ground,” and one person was ultimately arrested and charged.

Some in the public found the post dismissive toward what could have been a domestic violence event — particularly notable because then-Police Chief Justin Doll had pointed to domestic violence as a contributor to the current homicide rates, which had otherwise been declining.

Alaska’s News Source soon requested the name of the referenced arrested individual and was denied. APD claimed that it does not release additional information related to “What Not to Do Wednesday” posts. A subsequent request was met with a $6,400 fee.

FWIW, materials related to WNTDW are not valid exemptions under Alaska’s public records law.

By the end of February 2021, the APD decided to do away with the series.

“I think if you have an engagement strategy that ultimately creates more concern than it does benefit, then it’s no longer useful,” Chief Doll later said.

It’s not clear if APD is also applying this logic to its records process.

Do as I Say, Not as I Do Award — Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton

Texas law requires a unique detour to deny or redact responsive records, directing agencies to go through the Attorney General for permission to leave anything out. It’s bad news for transparency if that office circumvents proper protocol when handling its own records requests. It’s even worse if those records involve a government official — current Texas AG Ken Paxton — and activities targeted at overthrowing the democratic process.

On Jan. 6, 2021, Paxton — who is currently up for reelection while facing multiple charges for securities fraud and was reportedly the subject of a 2020 FBI investigation — and his wife were in Washington, D.C., to speak at a rally in support of former president Trump, which was followed by the infamous invasion of the Capitol by Trump supporters. Curious about Paxton’s part in that historic event, a coalition of Texas newspapers submitted a request under the state’s public records law for the text messages and emails Paxton sent that day in D.C.

Paxton’s office declined to release the records. It may not have even looked for them. The newspapers found that the AG doesn’t seem to have its own policy for searching for responsive documents on personal devices, which would certainly be subject to public records law, even if the device is privately owned.

The Travis County District Attorney subsequently determined that Paxton’s office had indeed violated the Texas open records law. Paxton maintains that no wrongdoing occurred and, as of late February, hadn’t responded to a letter sent by the DA threatening a lawsuit if the situation is remedied ASAP.

“When the public official responsible for enforcing public records laws violates those laws himself,” Bill Aleshire, an Austin lawyer, told the Austin American-Statesman, “it puts a dagger in the heart of transparency at every level in Texas.”

The Transparency Penalty Flag Award — Big Ten Conference

In the face of increasing public interest, administrators at the Big Ten sporting universities tried to take a page out of the ol’ college playbook last year and run some serious interference on the public records process.

In an apparent attempt to “hide the ball” (that is, their records on when football would be coming back), university leaders suggested to one another that they communicate via a portal used across universities. Reporters and fans saw the move as an attempt to avoid the prying eyes of avid football fans and others who wanted to know more about what to expect on the field and in the classroom.

“I would be delighted to share information, but perhaps we can do this through the Big Ten portal, which will assure confidentiality?” Wisconsin Chancellor Rebecca Blank shared via email.

“Just FYI — I am working with Big Ten staff to move the conversation to secure Boardvantage website we use for league materials,” Mark Schlissel, then-president of the University of Michigan, wrote his colleagues. “Will advise.”

Of course, the emails discussing the attempted circumvention became public via a records request. Officials’ attempt to disguise their secrecy play was even worse than a quarterback forgetting to pretend to hand off the ball in a play-action pass.

University administrators claimed that the use of the private portal was for ease of communication rather than concerns over public scrutiny. We’re still calling a penalty, however.

The Remedial Education Award — Fairfax County Public Schools

Once a FOIA is released, the First Amendment generally grants broad leeway to the requester to do what they will with the materials. It’s the agency’s job to properly review, redact, and release records in a timely manner, but after Callie Oettinger and Debra Tisler dug into a series of student privacy breaches by Fairfax County Public Schools, the school decided the quickest way to fix the problem was to hide the evidence. Last September, the pair received a series of letters from the school system and a high-priced law firm demanding the removal of the documents from the web and that they return or destroy the documents.

The impulse to try to silence the messenger is a common one: A few years ago, Foilies partner MuckRock was on the receiving end of a similar demand in Seattle. While the tactics don’t pass constitutional muster, they work well enough to create headaches and uncertainty for requesters who often find themselves thrust into a legal battle they weren’t looking to fight. In fact, in this case, after the duo showed up for the initial hearing, a judge ordered a temporary restraining order barring the further publication of documents. This was despite the fact that they had actually removed all the personally identifiable data from the versions of the documents they posted.

Fortunately, soon after the prior restraint, the requesters received pro bono legal assistance from Timothy Sandefur of the Goldwater Institute and Ketan Bhirud of Troutman Pepper. In November — after two months of legal wrangling, negative press, and legal bills for the school — the court found the school’s arguments “simply not relevant” and “almost frivolous,” as the Goldwater Institute noted.

The Foilies were compiled by the Electronic Frontier Foundation (Director of Investigations Dave Maass, Senior Staff Attorney Aaron Mackey, Frank Stanton Fellow Mukund Rathi, Investigative Researcher Beryl Lipton, Policy Analyst Matthew Guariglia) and MuckRock (Co-Founder Michael Morisy, Senior Reporting Fellows Betsy Ladyzhets and Dillon Bergin, and Investigations Editor Derek Kravitz), with further review and editing by Shawn Musgrave. The Foilies are published in partnership with the Association of Alternative Newsmedia. For more transparency trials and tribulations, check out The Foilies archives at EFF.org/issues/foilies.