Recently deceased art and culture critic Dave Hickey had a thing or two to say about the art world. Run by a class of people dubbed the “therapeutic institution,” the donors, curators, academics, collectors, and others who infringed on the democratic process defined beauty, he argued in his acclaimed set of essays, The Invisible Dragon. Beauty should instead rest solely in the viewer’s perspective, and everybody should get out of the way. By leaving the interaction solely to the viewer, opinions form, and democracy is indeed in action.

Hickey could have easily described Fort Worth’s therapeutic institution, which decides what is beautiful and, by extension, our collective memory. This small-town façade is nice. What’s not nice and is messy is the combination of alcohol, drugs, divergent opinions, and, perhaps, intellect. What’s nice is revisionist, such as the fantasies of Sundance Square and the Stockyards, and that’s all too evident in two new books, including one about Hickey and a recent art exhibition about very different Fort Worthians.

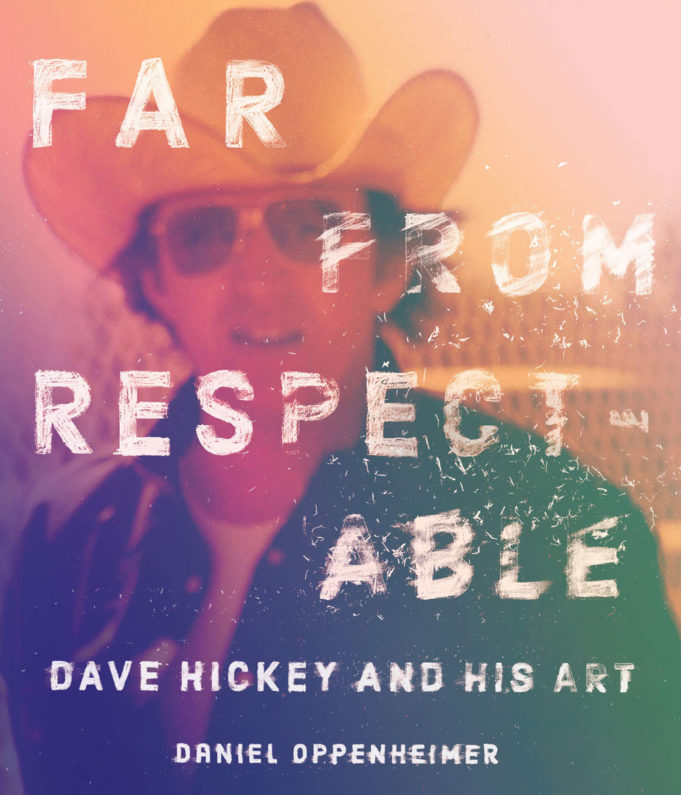

Hickey was born and raised here. He went to TCU, a source of hometown pride, yet he was conflicted about his relationship with Fort Worth and, by extension, Texas, according to the newly released Far from Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art by Austin writer Daniel Oppenheimer. In this loving biography of the late critic, we see why he did not meet Nice’s standards. One, Hickey was complicated and messy. He took drugs, was crusty, and was an intellectual flamethrower whose views pissed off all sorts of people, including many women artists, curators, and historians. He is also one of the city’s two known recipients of a MacArthur Fellowship or “Genius Grant,” with its coveted financial gift of $625,000 given to individuals with extraordinary talent in their fields. The other is Texas A&M School of Law Professor Thomas Mitchell, who received it last year.

Hickey described the city as “a very strange and private place, indeed — where the modalities of social interaction are virtually nonexistent, and the populace at large is segregated not only according to the traditional race, color, creed, and national origin but also according to age, sex, income, education, neighborhood, mode of transportation, and line of endeavor.”

In Fort Worth, he added, “being an asshole is optional — although it remains a very popular elective.”

Fear not, civic boosters: He also trashed Dallas.

Patricia Highsmith exemplified Hickey’s belief that an asshole is a standard option. The acclaimed fiction writer of books such as Strangers on the Train, The Price of Salt, which became the movie Carol, and The Talented Mr. Ripley was born and raised in Fort Worth and was an asshole. At any point during her life, including in Richard Bradford’s biography Devils, Lusts and Strange Desires released last year, she told her editor that she didn’t “like anyone.” That included at any point Arabs, Blacks, Catholics, Jews, her mother, and her partners’ husbands.

The city is not in the new book Patricia Highsmith: Her Diaries and Notebooks 1941-1995, but as the late writer Don Graham noted in Texas Monthly in 2004, the misanthropic and macabre Highsmith believed “her essential character was formed by age 6, and those first six years were spent in Fort Worth.”

Indeed, in Andrew Wilson’s 2003 biography Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith, she loved the feeling of living in a frontier town, among nature and ranches. She also loved women. She also fell in love here with a woman. In a 2016 Harper’s Bazaar article, British writer Jill Dawson learned then 6-year-old Highsmith, who hung out at Barber’s Bookstore downtown, also fell in love for the first time with a young woman named Rachel Barber. Highsmith’s sexuality was as central to her identity as anger, smoking, bigotry, and Fort Worth.

Highsmith, like Hickey, was messy. Messy does not please the therapeutic institution who willingly forget messiness and flaws are part of the human experience. They are clear examples that we are a breeding ground for some of the most creative, most intelligent people who were also angry and depressed critics. Those people, however, do not qualify for the Acceptable Certificate because, like Hickey and Highsmith, their flaws were so public that they made the Trinity River look bad.

So, who is acceptable, and what is beautiful? It’s those who also have access to status and class. They include the late twin painters Scott and Stuart Gentling, whose first retrospective recently ended at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art. The exhibition was fine — the museum is dedicated to this kind of art — but at the behest of Ed Bass, the Gentlings will also be forever memorialized at the Philip Johnson-designed building. A new research center there bears their name.

While they contributed to our cultural fabric, most notably with their Bass Hall murals, and were popular in social circles, they’re not getting recognized primarily for their art but for being the West Side’s acceptable oddballs. Their works are rendered museum-worthy and beautiful mostly because of their status, not necessarily their talent.

Yet the Gentlings, Hickey, and Highsmith can coexist. They liked Fort Worth. The question is if the ruling class will get out of the way and allow them all to be recognized.

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not the Fort Worth Weekly. To submit a column, please email Editor Anthony Mariani at Anthony@FWWeekly.com. Columns will be gently edited for factuality and clarity.