When I reviewed Nomadland, I remarked on filmmakers who find their homes far away from where they grew up. Wes Anderson is a Houstonian who has lived in Paris for some years, and you can imagine how the guy who made The Royal Tenenbaums and The Grand Budapest Hotel might find the City of Lights more congenial. The French Dispatch (of the Liberty, Kansas Evening Sun) is his love letter to his adopted homeland, and if you don’t share his Francophilia, this relatively minor work of his probably won’t convert you. However, if you do, or if (like me) you simply like his cinematic stylings, by all means have at this.

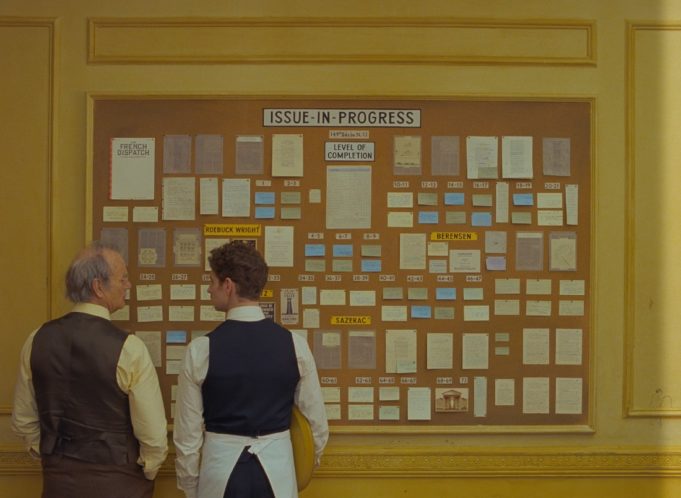

The film takes place in the fictitious city of Ennui-sur-Blasé, which sounds like a real drag, and is divided into discrete stories like the similarly titled magazine put out by editor Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray). This newspaper heir from the Sunflower State lands in this city as a young man in 1925, intending to take a sabbatical. Instead, he never leaves, spending the next 50 years publishing a Sunday supplement to his dad’s paper containing long-form pieces by American writers informing Kansans about French culture and European politics. This editor is a writer’s dream, coddling his talent, compensating them generously without bankrupting the mag, improving their writing without hurting their feelings, and indulging them with both deadlines and expense accounts. His obituary, which lays all this out, serves as a prologue sequence.

It’s followed by a travelogue by writer Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson), giving the history and geography of Ennui-sur-Blasé while riding his bicycle through town, and occasionally crashing because he’s busy narrating to the camera. If you know Anderson’s films, you’ll readily recognize the deadpan performances by a bevy of actors from his previous work (plus even more actors who aren’t) and his centripetal compositions. Somehow he manages to film a street riot fastidiously. He pulls every trick out of his cinematic bag: montages, stop-motion animation, drawn animation, changing frame sizes, theatrical scenes performed on stage sets, sequences shot in the style of French films from different eras. It’s all brilliantly done, although here more than in most of his work, it feels like cleverness for its own sake.

In the first story, “The Concrete Masterpiece,” J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton) delivers a pompous art lecture about her peripheral involvement with Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro), the Jewish-Mexican-French homicidal psychopath who learns to paint in prison. He becomes famous when his abstract expressionist nudes of a guard who obsesses him (Léa Seydoux) are sold by a renowned art dealer (Adrien Brody) whom he meets in lockup. While Anderson’s art-world satire turns up some tasty nuggets — the dealer goes from ecstatic to furious when he learns that Moses’ magnum opus is frescoed into the prison walls, and thus impossible to sell — many other films have been more cutting, including the recent Candyman reboot.

Story No. 2 is titled “Revisions to a Manifesto,” in which Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand) chronicles the student protest movement and her affair with Zeffirelli (a shock-haired Timothée Chalamet), its much-younger leader. The film scores points about how doctrinaire revolutionaries can be, especially ones who are young and French — Zeffirelli’s girlfriend (Lyna Khoudri) says about a pop singer, “He is a commodity produced by a record company owned by a conglomerate subsidized by a bank. Every note he sings, a West African peasant dies!” Chalamet is quite good, too, as a doomed boy whose self-absorbed belief that he can change society makes him beautiful. Still, the political satire is damp stuff as the students fall into silly disputes both with the police and among themselves.

The best and most substantive story is saved for last. In “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) tracks the heroic efforts of a police lieutenant and legendary chef named Nescaffier (Stephen Park) during a night when his boss’ young son (Winston Ait Hellal) is kidnapped by gangsters. The food writer Roebuck may be based on James Baldwin and A.J. Liebling, but he acts as a stand-in for Anderson, whose movies are notably food-obsessed. The genre of cuisine that Nescaffier invents, “police cooking,” is described in funny detail. Wright gives the film’s best performance as a lonely Black Southerner who seeks solace and companionship in his meals because they’re missing from his life. He’s particularly moving when Roebuck is imprisoned for homosexuality and receives a job offer from Arthur — with just the words “Thank you,” you know that the employment is this man’s lifeline. Possibly sadder are Nescaffier’s words after he narrowly escapes death and tells Roebuck that he found a wonderful new flavor in the poison he ingested. Both of these expatriates bond over the idea that what you love can kill you. Pretty dark.

The movie is intended as a salute to The New Yorker, and I am reviewing it for a publication that’s much like The New Yorker in concept. (In execution? You be the judge.) I travel to the far corners of the cinematic world and report back to you, dear readers, because some of you are curious about what I’ve found. It is great to take in a truly great or unique film, but the real joy comes from telling all you curious and cultured Middle Americans about it in my way. The French Dispatch is only fitfully great or unique, yet because it knows that this same joy drives its writer characters, it is treasurable.

The French Dispatch

Starring Bill Murray, Owen Wilson, Tilda Swinton, Frances McDormand, and Jeffrey Wright. Written and directed by Wes Anderson. Rated R.