Diane Wilson was familiar to physically grueling and mentally challenging situations, but nothing prepared her for the 150-day sentence to the Victoria County Jail she received in 2006. The fourth-generation shrimper, writer, and activist frequently went on hunger strikes for weeks on end in confined spaces like her truck to raise awareness of pollution and other forms of environmental destruction.

“The worst trauma that I have ever experienced was in a Texas county jail,” she said, referring to her experience in Victoria’s jail. “They didn’t have blankets. They usually have a little place to brush your teeth. You had a 1-inch toothbrush. I was sleeping on the cement floor. Some of the stories were horrendous.”

Before her arrest and subsequent imprisonment in Victoria, located about 110 miles southeast of San Antonio, Wilson had climbed a tall tower within a Union Carbide factory. After disguising herself as a worker, she was able to slip into the facility with a banner that read, “Dow, Responsible for Bhopal,” a reference to the 1984 chemical spill that killed an estimated 20,000 men, women, and children in the Indian city.

“I was there eight hours,” Wilson said. “They couldn’t figure out how to get me down. They brought in a 100-foot crane. They had a SWAT team on it. The DA said I was the most dangerous woman in Texas.”

One letter sent to the Victoria County’s sheriff around that time has become something of a founding document for Texas Jail Project, a nonprofit that was formed after Wilson’s imprisonment to empower incarcerated people in Texas county jails.

Dear Sheriff O’Connor,

I am a female inmate in the Victoria County Jail, TX, though I was arrested on criminal trespass charges in Calhoun County. I was given a sentence of 150 days plus a $2,000 fine for protesting Dow Chemical Company’s refusal to appear in Indian courts in response to charges against its wholly owned subsidiary, Union Carbide, and its treatment of the survivors of the toxic leak disaster in Bhopal, India, where a catastrophic pesticide release has killed over 20,000 people to date.

The women in this jail are predominantly African American or Hispanic and very poor. Most of their offenses are minor, for things like traffic tickets or soliciting or violating probation — all nonviolent, yet they are forced to remain in the cell without counsel for long periods of time.

Texas Jail Project has grown to become a prominent advocate for jail reform in Texas.

To raise awareness of atrocities that occur in Texas jails on a daily basis, the nonprofit recently published report cards. Tarrant County’s results highlighted the 2020 death of Javonte Myers, the 28-year-old Black man who was held in Tarrant County Jail for criminal trespassing, a misdemeanor offense that disproportionately affects Black men and women in Tarrant County (“ White Customer, Black Trespasser,” Aug. 2020). Myers, who was chronically homeless, could not afford to post bail, his mother told the Star-Telegram that year.

Courtesy of Texas Jail Project

District Attorney Sharen Wilson, who recently announced that she will seek reelection in 2022, told the Star-Telegram at the time, “Yes, homeless people who commit crimes are prosecuted in Tarrant County.”

The report card notes that the jail’s population has grown 36% since 2016. Just over 2,500 people in the county jail are pretrial, meaning legally innocent. Tarrant County Jail has a capacity of 5,000, according to the county.

Local taxpayers spend $26,445 a year to confine each person held, according to Texas Jail Project, meaning Tarrant County spends about $109 million a year to confine largely legally innocent and poor defendants. Texas Jail Project received 24 complaints of neglect and abuse at Tarrant County Jail in 2020.

A spokesperson for the Texas Commission on Jail Standards (TCJS) said that they received 393 pages of complaints about Tarrant County’s jail over the past three years. Copies of those documents were recently provided to the Weekly, and we will report on the findings in the coming weeks.

County jails across Texas process men and women who have been arrested, typically for a Class B Misdemeanor and higher. Certain defendants are held indefinitely if they are deemed a threat to the public or if they cannot afford bail.

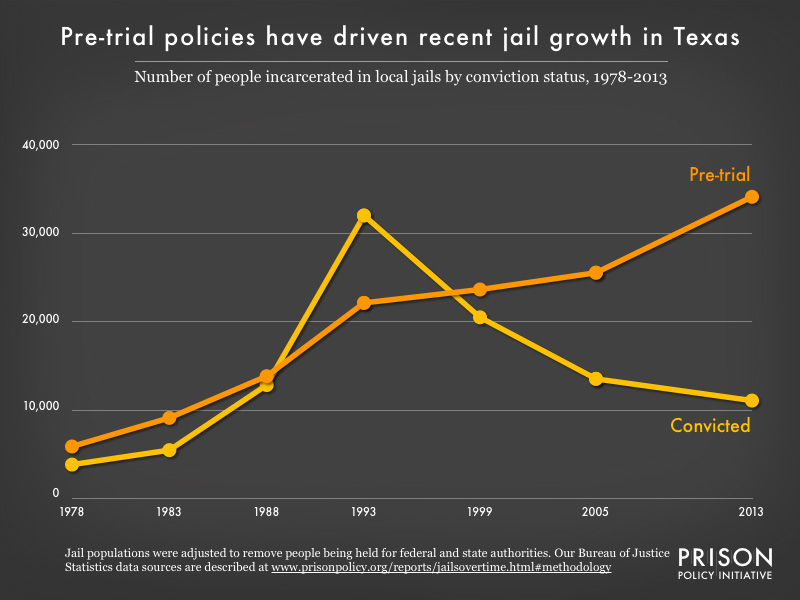

A 2018 report by the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Austin, found that the proportion of pretrial defendants in Texas jails has drastically increased over the past 25 years: from around 50% in 1993 to 74% in 2018.

Diana Claitor, Texas Jail Project communications director, said much of that trend can be tied to Texas’ reliance on monetary bond — the American legal custom of requiring monetary deposits as a condition of release from jail.

“If you don’t have money to bail out, you are stuck in there,” Claitor said. “We have military veterans who have been in Harris County Jail for 13 months on low charges. It is a dangerous place to be.”

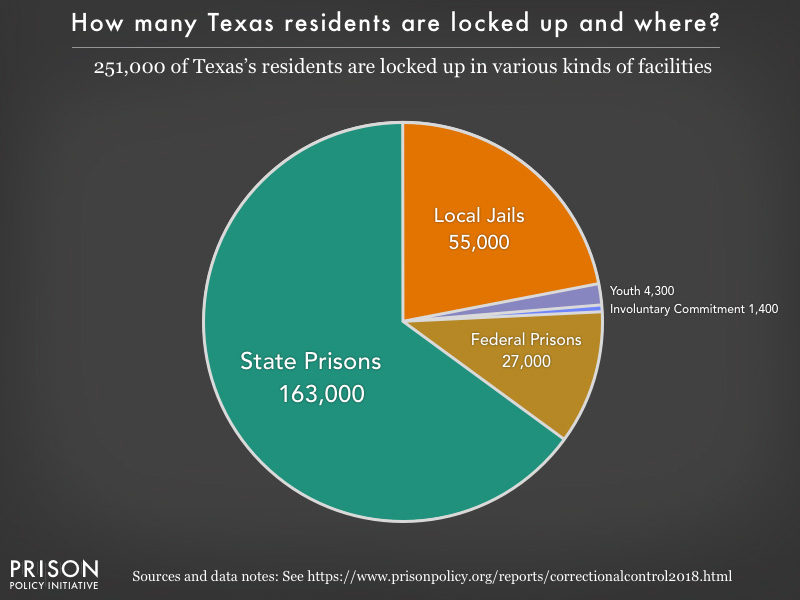

Courtesy of Prison Policy Initiative

In the wake of civil unrest following the 2020 murder of George Floyd by a white police officer as three officers looked on, communities across the country began forming bail funds. The Tarrant County Community Bail Fund was created last year in response to the lack of compassionate releases from the local county jail. The fund has released dozens of nonviolent Black and brown defendants to date. So-called bail reform efforts by conservative Texas legislators seek to end the practice of charitable bail payments because the charitable payments weaken the bail system, bail bond supporters allege.

Claitor said her nonprofit is speaking to state representatives and senators about the dangers of continuing or expanding the state’s reliance on monetary bail practices that too frequently criminalize poverty.

Recently passed House Bill 1307, which Texas Jail Project staff advocated for, requires jailers to provide pregnant women professional medical attention and access to counseling following a miscarriage or sexual assault. The law applies to women who are in county jails or in the custody of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ).

Texas Jail Project recently hired a community organizer who lives and works in Fort Worth. The new staff member will enable Texas Jail Project staff to closely follow jailing practices in North Texas and to network with other advocacy groups and mental health service providers.

******

Diane Wilson said one young Black woman’s story still haunts her.

“She and I were the only two in that jail cell,” Wilson recalled of her 2006 imprisonment. “It was New Year’s Eve or Christmas Eve. She told me this awful story about how her baby died. She had a warrant out for a hot check. She was also pregnant. They arrested her, pulled her in, and threw her in jail. When she started complaining about problems with her pregnancy, they did not believe it. They always think that whoever is in jail deserves to be there. They don’t care. They threw her in solitary with a paper gown. She went into labor. They don’t like you pushing the call button. They ignored her. She delivered the baby in jail, and it died.”

The mother told Wilson that she was not allowed to attend her own baby’s funeral. Last summer, a woman who was detained at Tarrant County Jail gave birth while unattended by jailers. The baby died 10 days later in a hospital, and the mother was subsequently placed in a mental health hospital, according to reporting by the Star-Telegram at the time.

Photo by Edward Brown

“We were encouraging Diane to write down what she saw,” Claitor recalled of the time. “The pieces became known as Letters from the Victoria County Jail. That was the initial force behind [what would become Texas Jail Project]. We told her that we would take [the letters] to Austin. We found out that no one wanted to be accountable. When we decided to start a nonprofit, I put a notice on Craigslist asking for someone who could build a website for free to help women who were incarcerated. At this point, we thought we would only help women. The moment we put the website up with my phone number and email, it was like nothing we expected. It was shocking. We started answering questions as best we could. We were overwhelmed by complaints and pleas for help. We started out by helping people file a complaint with the Texas Commission on Jail Standards.”

Ann Wright, a retired Army colonel and Texas Jail Project co-founder, visited Wilson during her incarceration at Victoria County Jail. Wright said the stories shared by Wilson galvanized the three other co-founders, Claitor, Krishnaveni Gundu, and Wilson.

“The four of us decided to shine a light on county jails,” Wright recalled. “As we dug into it more, we kept hearing these horrible stories. We put up this website and started calling families to hear the stories of what their loved ones had been through. We started posting, without names, that this or that has been going on. In the early days, we had something called the Hell Hole of the Month Award. We would identify some of the latest abuses at some county jail and put out a press release, then have a demonstration out in front of that jail. That got publicity in the local newspaper.”

Gundu, who currently serves as Texas Jail Project executive director, said the nonprofit’s early work involved visiting meetings by county commissioners across the state and TCJS.

“We were asking for accountability,” she recalled. “We thought someone would take over this work.”

As Gundu and the other co-founders spoke to nonprofits that were involved in criminal justice reform, the four friends realized that no group was focused solely on the treatment of county jail populations.

In 2009, Texas Jail Project had a legislative victory. Through advocacy work with state legislators, two bills were passed and signed into law that year. HB 3653 bans the shackling of women during labor and delivery in Texas jails while HB 3654 established record-keeping standards for pregnant prisoners. Texas Jail Project was subsequently able to use the data to estimate that around 5% of female county jail prisoners are pregnant at any given time.

“We saw how it went from listening to people to changing policy,” Gundu said. “That’s when it really sunk in. In 2012, we gained our IRS 501c3 [charitable] status. It became hard to only focus on women’s issues. We were finding out that no one else was doing what we were doing. More and more people were reaching out to us. Now we are finding that 80% of the cases we look at involve people with intellectual disabilities or mental health conditions.”

Texas Jail Project program associate Gabriela Barahona said that a broader cultural awakening of the systemic injustices that lead to overcrowded jail populations has happened in the United States.

“Since the 1980s, we’ve been fed a pretty lazy cultural description of crime and criminals, one that we absorbed through TV shows about police and policing and a culture of otherizing people who have less money than us,” Barahona said. “It is easier to put the problem behind walls where you don’t have to look at them anymore. It is a problem with unhoused people. We don’t want to see them in our neighborhoods even though they are our neighbors and even though the cost of incarcerating someone is more expensive than giving them a home.”

To whom it may concern,

My name is Douglas. I am incarcerated in Harris County jail. I am in the 177th Judicial District Court [with] the Honorable Judge Robert Johnson. My rights are being violated. I have requested to dismiss [my legal] counsel but been denied. There are several other issues also. I am indigent … and I have no help. What can I do? Please advise.

Douglas A.

The letter, viewable at SheddingLight.in/Texas/Stories, is one of more than 100 first-hand accounts that Texas Jail Project staff compiled last year during the pandemic.

“When COVID hit, we opened up our phone lines,” Gundu said. “We didn’t have a budget or plan. That’s how Shedding Light happened. What we heard was that [prison populations] were quite literally starving. They weren’t getting enough food. We started doing direct aid, which we had rarely done before. We couldn’t watch and listen to what was happening and not render aid. We were funding commissary accounts because families were not able to support their [jailed] loved ones.”

A November 2020 article by VOX found that 80% of Texas jail population deaths involved innocent detainees. By that time, more than 230 people died from COVID-19 in Texas prisons and jails, according to data from the TDCJ.

The Texas Jail Project team created a revolving bail bond fund for Smith County, about 100 miles southeast of Dallas. A jail reform advocate in Smith County developed a relationship with the county’s sheriff, which helped facilitate the program, Gundu said.

“They were still arresting people for misdemeanors” in the county, Gundu said. “The bail fund came as a result of the support of the sheriff. If it wasn’t for us, there would have been people taking plea deals that they shouldn’t have.”

Courtesy of Prison Policy Initiative

Last summer, volunteers with the grassroots group United Fort Worth started a bail bond fund to release indigent Black and brown members of the Tarrant County Jail population (“ Criminalizing Poverty or Ensuring Justice?” July 8, 2020). Pamela Young, lead criminal justice organizer for United Fort Worth, told me at the time that concerns over COVID-19 and the sheriff department’s refusal to allow the compassionate release of nonviolent offenders necessitated the bail fund.

A Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office spokesperson said in an email that her department follows recommended health guidelines set forth by the Tarrant County Health Department, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, and John Peter Smith Hospital staff.

“Additional precautions include the continued wearing of masks and other protective gear, frequent disinfecting of facilities, minimized movement of inmates between facilities, increased video court hearings, and the halting of outside volunteer programs,” the spokesperson said. “Our team members have been battling COVID-19 for over a year and will continue to work hard to stave off the impact and prevent the spread of it inside our facilities.”

Overcrowding has exacerbated COVID-19-related deaths in county jails. A 2018 report by Texas Public Policy Foundation found that financial incentives increasingly drive jail capacities.

“Economic factors can explain increases in contract holdings in local jails,” the report read. “Overcrowding in state and federal prisons creates high demand for bed capacity. As local jurisdictions build out additional beds to address their own concerns, they have a ready incentive to use any unused capacity — or even to build capacity beyond their immediate needs — to house other inmates for financial remuneration, which can range between $25 and $169 per person.”

The local sheriff’s department spokesperson said Tarrant County doesn’t contract with private or state prisons to hold prisoners in exchange for fees.

Counties, the jail project’s Claitor said, “could do a lot of different things that would save them a tremendous amount of money and prevent lawsuits.”

Claitor, Gundu, and other members of the Texas Jail Project team spent much of July warning state legislators about a gubernatorial priority, so-called bail reform, that aims to kill charitable bail programs like United Fort Worth’s Tarrant County Community Bail Fund.

Like all Republicans, Gov. Greg Abbott believes charitable bail programs are freeing hardened criminals.

“Public safety is at risk because of our broken bail system that recklessly allows dangerous criminals back onto our streets,” he said just ahead of the current special legislative session.

Republican legislators are currently unable to pass voter suppression laws and so-called bail reform measures because Democratic state lawmakers have fled to Washington, D.C., and deprived Texas Republicans of a quorum.

“We have testified during the regular session against this so-called bail reform, which is basically expanding detention pretrial,” Claitor said. “Their idea is to incarcerate more people and to place more restrictions on who can be released on bond. They don’t want any charitable bail bond programs. This legislation is based on public safety, but they fail to note how many people have died in jail. They portray it as keeping mass murderers locked up. We are showing how many of these unconvicted people are not a danger to the general public.”

******

Prisoner executions were comparatively low in 2020. The State of Texas put three inmates to death last year, considerably down from a 2000 peak of 40 executions. Last year, as COVID-19 swept through overcrowded county jails across the state, 20 members of the Tarrant County Jail population died, according to Texas Jail Project. The local sheriff’s department put that figure at 17.

Tarrant County leadership is working to create a mental health jail diversion center that would spare individuals who are having a mental health crisis from being jailed. The idea is to give law enforcement an alternative destination for anyone who is arrested or picked up by peace officers. At the moment, Tarrant County Jail is often the only place law enforcement can take men and women who are experiencing a mental health crisis.

In June, Tarrant County approved a new cite and release program that allows minor offenses to be ticketed, which would potentially spare thousands of nonviolent offenders from having to endure the trauma of being held in Tarrant County Jail.

“Tarrant County is unbelievably late to the party,” Claitor said. “When you look at what cite and release has done across the country, in terms of the amount of people you save from going to jail and the amount of money saved, it’s phenomenally successful for the most part. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had to talk to a mother of someone who was arrested for criminal trespass who then kills themselves. It is beyond ridiculous that we feel this driving need to incarcerate, incarcerate, incarcerate.”

Wright said she is excited to see how Texas Jail Project has grown to include a handful of paid staff. Much of the nonprofit’s work has historically relied on volunteers, she said.

The younger generations in Texas are much more aware of systemic injustices caused by the U.S. criminal justice system, she said.

“There is the Prison Abolition movement, which calls for the abolition of the incarceral system,” Wright said. “It isn’t a popular mainstream idea. Our society still believes that you have to punish people and put them in jail. That’s the only way they will learn their lesson. Young people are calling attention to injustices that we see in the entire judicial system, including who is picked up by the police, what kind of bail is given, how long they stay in pretrial confinement, and what types of sentencing are done. That whole system is under scrutiny by a small but vocal group of young people. Whether or not they are able to effect change in the legislative bodies that hold the power over these institutions is yet to be seen. The cycle is very hard to break of how we as an American society look at prisons. The fact that the U.S. has more people in jails than any country in the world shows that everything about the jailing system is a moneymaker for someone.”

Gundu said the sheer size of many Texas jail populations is dehumanizing to the men and women held in those institutions.

“When you are dealing with 8,000 or 9,000 people, there is no way for anyone to do their jobs and not be desensitized” to the system, she said. “If you could cut down the jail populations, automatically, the policies, attitude, and culture would be better. It wouldn’t be perfect, but it would be easier. [Jailers tell us that they] can’t get through the days if they are not ignoring the majority of those concerns. Some do try to do their jobs ethically.”

Barahona said Texas Jail Project’s staff have to look at the systems that feed detention buildings.

“The county jail staff does not choose who they are confining,” Barahona said. “Those people are sent by the court systems, prosecutors, judges, and poverty. We can’t do our work by only looking at the four walls of the building. We have to look at the systems that funnel people into them. Even with the best facility possible, are we still undervaluing what liberty is because the majority of people being held are legally innocent? Even if we were holding them in a Holiday Inn, what does it mean that they are not with their family, seeing their general practitioner, or going to church every Sunday?”

Most county jails are not designed for long-term detention, she continued.

“They were designed to hold people for very small periods of time,” she said. “For a number of reasons, county jails are holding people for longer and longer. There is an overall increase in the number of charges, and there are backlogs in the courts. The average person has been in Harris County Jail for 212 days. We have worked with people who have been confined for five years who haven’t had their trial.”

In the coming weeks and months, the co-founders said Texas Jail Project, with the help of their new community organizer, will begin building close relationships with local mental health groups, county officials, and like-minded advocates. Gundu and Barahona said Texas Jail Project staff will seek a seat at the table as Tarrant’s mental health jail diversion center and other projects are implemented.

“There are so many systems that touch and interact with the jail system that our work has to be fairly broad,” Barahona said.

An activist invades company property and scales a tower, requiring a 100′ crane and SWAT team to remove her, then says jail was traumatic? We need more jailing for people like this.

Hi Jimmie. This is the author. I encourage you to learn about the life of Diane Wilson, the woman you are commenting about. I was honored to speak with her, especially after learning about all the good she has done over her lifetime. After you learn about this great woman, you can reflect on the important role civil disobedience has played in this country. Then, you might be able to begin to understand the role she and other people have played in pushing this country past the cesspool of ideas that you encapsulated in your quote. Regards, Eddie

Thank you for your comment regarding Diane Wilson. Texas Jail Project has helped so many people in Texas, me included. I am proud of Diane Wilson and all the work that the Texas Jail Project has done to improve outcomes in Texas. Thank you so very much for publishing this article!