The Kimbell Art Museum’s summer exhibit made me wish that I knew more about the intricacies of ceramics and metalworking. It’d sure be nice if the show gave us some insight into how an eighth-century Chinese silversmith hammered a single sheet of silver into the ornate Tang Dynasty stem cup. Nevertheless, if there’s one thing I take from this, it’s that the whole of Eastern Asia, despite some impressive physical barriers of ocean and mountains, was united by commercial trade and the threads of Hinduism and Buddhism.

Photograph by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts

That’s certainly stronger than the stated theme of Buddha Shiva Lotus Dragon, which is that all these items were collected by John D. Rockefeller III and his wife Blanchette Rockefeller during their frequent trips to Asia in the mid-20th century. Much like the Kimbell itself, they did not have a specialty, instead collecting whatever caught their discerning eye and being selective about quality.

Photograph by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts

Undoubtedly, one of the big draws of this show is its Chinese ceramics. The eggshell-blue stoneware bowl from the 12th-century Song Dynasty has splotches of purple that come from copper filings sprinkled over the glaze prior to firing, giving the tiny object an uncannily modern look. The larger pieces such as a Ming Dynasty flask and platter sport the familiar cobalt blue patterns. What I find interesting about these is their size, which indicates that they were made not for the domestic Chinese market but rather for the Middle East and India. (Indeed, the platter comes from the collection of Shah Jahan, the ruler who built the Taj Mahal. The big dish was intended for use in communal dining, which was popular in India at the time and only caught on later in China.) A magnificent Yuan Dynasty jar’s red copper decoration is marred by grayness near the top, a sign that the kiln operator overfired the finicky glaze. The Kimbell’s written notes for the items curiously omit the influences that filtered into Chinese art from Islam but otherwise do great work at pointing out small, significant details in the decoration.

Photograph by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts

China became so synonymous with ceramics in the West that we call porcelain “china” as a matter of course, but it wasn’t the only place making good pottery. The show also contains two delightful 17th-century Japanese figures of courtesans that appear to have been made for Europe as well as a carefully wrought Korean bowl with a leaf shape and the country’s signature green glaze. Thailand and Vietnam are represented here as well, as different parts of Southeast Asia developed their own versions of the art practiced to their north.

Photograph by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts

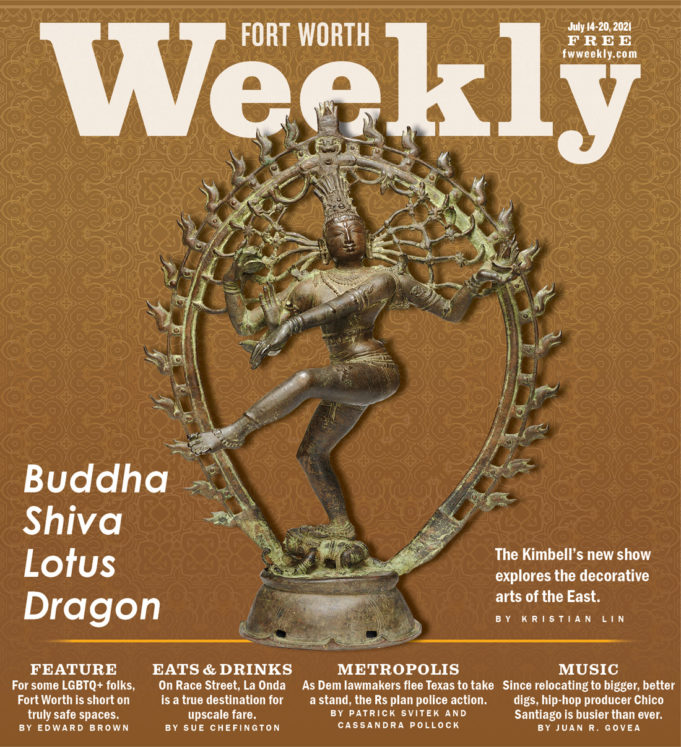

The other main attraction are the bronze sculptures from India’s Chola period in the 9th through 13th centuries. Hinduism and Buddhism existed side by side — some artists made shrines for both these Indian religions — and the sculptures of gods and saints were intended to be covered with clarified butter and honey as part of temple worship. The 11th-century statue of the god Ganesha sports entrancing surfaces on its potbelly, elephant head, and four arms. It comes with lugs at the base that indicate that it was intended to be carried at the front of a religious procession. Even more spectacular is the earlier statue of Shiva as lord of the dance. I can only guess (again, because I’m not a metalworker) what it took to render the fiddly bits with the god’s matted hair flaring out while a wheel of holy flame surrounds him.

Photograph by Synthescape, courtesy of Asia Society and American Federation of Arts

If you’re looking for evidence of what perspicacious collectors the Rockefellers were, Buddha Shiva Lotus Dragon will give you plenty of it. If you want to admire the beauty of the individual pieces themselves, there’s lots of grist for the mill. However, I came away thinking about how connected these distinct parts of Asia were through business and art. A different show could say more about this subject.