Just hours after the Weekly published a leaked email online, staff videographer Wyatt Newquist left a voicemail on my cellphone.

“Two police officers stopped by asking for you,” Newquist said.

I immediately called our office and was given the phone number of one of the officers. The detective told me that I was the lead suspect in the theft of a document and that the two detectives needed to speak with me the following day at their Northside headquarters.

The detectives were seeking the source of a leaked email that was originally sent to Fort Worth school board trustee Tobi Jackson from her lawyer in 2016. Multiple media outlets, including the Weekly, had reported that Jackson’s employment at the time with SPARC, a local nonprofit, conflicted with her school board dealings with a prominent law firm, Linebarger Goggan Blair & Sampson, due to the fact that a Linebarger partner was an active board member (effectively a donor) at SPARC.

Jackson maintained that she had a legal opinion that stated there was no conflict. The school board trustee refused to release that legal opinion, and, once we received the legal memo, it became clear why (“ School Board Ethics,” April 2019). The lawyer did not explicitly state that there was no conflict of interest but rather that Jackson “may choose to abstain to avoid the appearance of any impropriety.”

Newspapers and journalists are honor-bound to not disclose the identity of confidential sources. Even with the broad protections afforded the press under the First Amendment, American journalists have been detained or jailed for not releasing the identity of their sources.

“Declaring no one to be above the law, a federal judge sent The New York Times reporter Judith Miller to jail yesterday for refusing to divulge a confidential source to a grand jury investigating the disclosure of a CIA agent’s identity,” reads a 2005 article in the Baltimore Sun.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning Miller spent 85 days in jail before finally agreeing to testify.

Following initial detention, Miller told the federal court that “the freest and fairest societies are not only those with an independent judiciary but those with an independent press, publishing information the government does not want to reveal.”

I called my source, local political consultant Travis Parmer, about the investigation, and he agreed to meet with the officers and to out himself as the person who leaked the document. The next day during my questioning, I had the impression that the beat officers would rather be doing anything else than looking for the source of an allegedly stolen email. While making small talk, I learned that the officers were tasked with solving auto theft and other property thefts.

I answered their questions and gave them Parmer’s phone number. Parmer never explicitly told me how he found the email, but in my eight years of experience as a reporter, I know that public information officers occasionally release confidential documents by accident and that embarrassing or incriminating documents are not infrequently leaked to the press by whistleblowers. The idea that someone physically broke into Jackson’s office and stole the document defied belief.

I saw the entire exercise as an act of intimidation on the part of Jackson and a reminder that law enforcement remains a potent tool of the well-connected.

Parmer said in an email that he received the email through an open records request. Someone in the school district accidentally released or intentionally leaked the email that was part of a larger thread Parmer had requested.

Fort Worth’s “tolerance for political corruption seems almost limitless,” he recently told me. “I do sometimes wonder if anybody ever investigated the fact that ‘somebody’ was responsible for intentionally filing a false police report as a piece of political theater. I’ve lived in Fort Worth long enough to know that the answer is no. Ms. Jackson, the board member who started this whole thing by misleading the public, was just elected president of Fort Worth school board.”

A 2019 report by Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP), a nonprofit that provides news organizations with free legal advice, outlined 50 pages of perils faced by journalists and media outlets. Prior restraint, the practice of preemptively banning the publication of information, is on the rise, even though the U.S. Supreme Court has consistently struck down such unconstitutional orders, reads part of the RCFP report. There were seven documented instances of prior restraint placed on media outlets in 2019, a sharp rise from one such incident in 2017 and five in 2018.

“Courts often issue these orders when a court or a litigant inadvertently discloses documents to the press and then tries to claw them back,” the report read, even though leaked documents are perfectly legal to publish if they are newsworthy.

Reporters also face a rising trend of court-ordered subpoenas, which require journalists to testify in court or to hand over documents. RCFP’s reporting found that 2017, 2018, and 2019 saw eight, 25, and 27 subpoenas issued to journalists, respectively.

“This increase is notable because subpoenas can impose a significant financial, emotional, and professional burden on journalists and news outlets,” RCFP said. “If a journalist refuses to comply with a subpoena to protect a source or sensitive work product, he or she can risk jail time or hefty fines. Troublingly, several journalists and news outlets reported that they believed, based on the circumstances, that they were subpoenaed as a form of retaliation or harassment in response to critical reporting or the filing of a court access or public records lawsuit.”

The possibility of libel suits, court subpoenas, and the targeting of confidential sources hasn’t stopped media outlets like the Weekly and many others from performing that most important of journalistic functions — publishing embarrassing or compromising documents that government officials and special interests would otherwise hide from the general public.

*****

Photo by Vishal Malhotra.

Proponents of gun rights often speak of “exercising their Constitutional rights” to carry firearms under the Second Amendment. The idea is that the right to bear arms must be protected by continually asserting that right through the open or concealed carry of guns in public.

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and ’60s tested the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment as Black men and women asserted their right to vote or use segregated public and private spaces like restaurants and the front end of city buses. Those efforts, while ultimately successful, were often met with violence in the South.

Newspaper and online media outlets similarly protect the broad press freedoms afforded under the First Amendment by publishing information that is culled through state and federal public information acts, confidential sources, and the scouring of publicly available data.

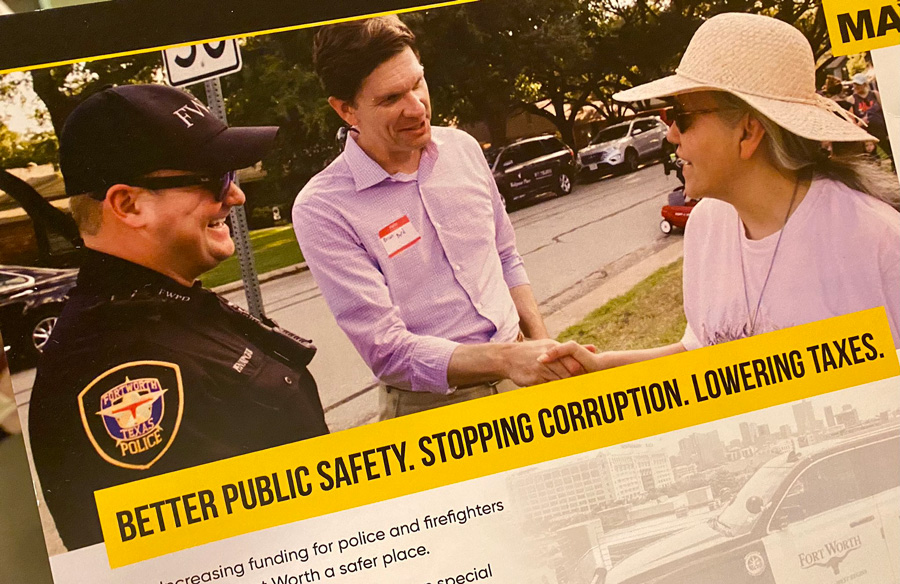

Sometimes, newsworthy information is readily accessible but missing context. The recent mayoral race led local media outlets to sleuth campaign contributions. Most articles tallied war chest numbers and provided context on which groups were backing whom. By going several steps further — connecting donor names with business entities, then searching for city contracts awarded to those businesses — the Weekly found a consistent pattern of campaign contributions being followed by the awarding of tens of millions in city contracts to former city councilmember Brian Byrd (“ City Contracts Worth Tens of Millions Tied to Brian Byrd Campaign Contributions,” April 20).

While no single city councilmember holds the power to award contracts that are vetted by city staff before being voted on by nine councilmembers (if the contracts are valued over $50,000), the consistent link, over four years, between campaign contributions and contract awards meant that there was a compelling public interest in having those connections published.

Unethical campaign contribution dealings rarely violate the state’s lax ethics rules, as I was recently told by an individual with intimate knowledge of ethics laws. Often, the only accountability comes from the publication of information detailing campaign contributions and kickbacks, he said.

Our recent reporting on the cozy relationship between Tarrant County’s tax assessor-collector, Wendy Burgess, and Linebarger (“ Keeping Tabs on TAD,” Jan. 6) caught the attention of Daniel “Joe” Bennett, who unsuccessfully ran for one of five seats on the board of the Tarrant Appraisal District (TAD) in 2017. Around the time Bennet was running for the board opening, which is voted on by taxing entities and not the general public, he received a nondescript package.

“I paid no attention to it at the time,” he recalled. “A couple of weeks later, I opened it, and it is from a whistleblower. I kept getting whistleblower letters. I received nine of them.”

The TAD whistleblower letter outlined alleged inter-office affairs between high-ranking TAD staff and subordinates, workplace harassment, accusations that one TAD leader lied to a state senate panel, and one documented instance of a TAD staffer telling employees to hide software problems from the general public (“ Shining a Light on TAD,” June 2). Those software glitches were later widely reported in the press as tens of thousands of Tarrant County residents began receiving irregular property tax billing statements.

Bennett had the whistleblower letter in his possession when he asked TAD for their copy via an open records request. The request was a test of TAD’s commitment to openness and transparency, Bennett said. The appraisal district responded by appealing to the state attorney general’s office, seeking to withhold the document. When that failed, the district sued the AG. The litigation went on for several months, costing Tarrant County taxpayers at least $15,000 in legal fees, before the suit was dropped in late 2018, according to court documents.

Photo by Edward Brown.

Bennett closely follows TAD dealings, and he estimates that roughly 90% of the details in the whistleblower letter were credible. To this day, he doesn’t know whether the anonymous public informant is male, female, one person, or a group of people, although he believes, based on the wide range of sensitive information, the leaked information came from multiple departments within TAD.

There are any number of reasons why a current or former employee may turn to the media to leak sensitive information. If the place of employment has a toxic work culture, approaching the human resources department can lead to professional consequences for the whistleblower.

That often leaves local media as the only safe and effective source for publicizing alleged indifference toward COVID-19 during a pandemic (“ COVID Concerns,” Oct. 2020) or audio recordings of a local high school principal directing teachers to fudge grades (“ Slowing the COVID Slide,” Mar. 2021).

Whistleblowers and confidential sources are increasingly the target of local and federal aggression and prosecution, according to RCFP. The U.S. Department of Justice sought to prosecute the source of government leaks once in 2017, four times in 2018, and three times in 2019.

“The Trump administration has now prosecuted eight people in three years,” the report read. “These prosecutions continued a trend started by the Obama administration, which prosecuted 10 leaks over eight years (mostly in President Obama’s first term, however). The government has typically prosecuted these disclosures by claiming they violate the Espionage Act, a vaguely worded law enacted in 1917 to combat spying that criminalizes the disclosure of government documents and information.”

*****

The Fort Worth police department was founded in 1876, but comprehensive access to documented police infractions was not publicly available until a few months ago. The 37-page ledger that documents incidents of police misconduct was first published in the Weekly in the fall (“Large Document Reveals Misconduct by Fort Worth Police,” Nov. 2020). The police reform-minded grassroots group No Sleep Until Justice requested the data last summer. Fort Worth’s Secretary’s Office responded with a $1,731 bill in August. The city is not obligated to bill folks who request records, and those onerous asks for payment are commonly levied on groups and newspapers seeking embarrassing or potentially incriminating information on city officials or police.

Speaking at the time, No Sleep Until Justice president Thomas Moore said, “Fort Worth police department does not hold their officers accountable in an appropriate manner, which undermines the public trust in police, wastes taxpayer money, and keeps everyone less safe.”

The 37-page ledger includes infractions from active-duty police officers, and those violations include: false report, weapon violation, neglect of duty, assault, illegal search, rough handling, failure to take action, discourtesy, untruthfulness, and theft, among many other types of violations. At least one officer listed on the ledger works for the Office of Internal Affairs, the office tasked with investigating allegations of police misconduct.

The Fort Worth police department’s Public Relations Office routinely denies or delays requests for complaints against police officers that I routinely file as part of my reporting (“ Closed Records,” June 16). The city Secretary’s Office filters open records requests to keep embarrassing information from the public, and similar efforts are made by the Tarrant County District Attorney’s office when requests for communications are made for county officials.

Local government’s handling of open records requests through the Texas Public Information Act became such an issue for our newspaper that we made public information requests the topic of a recent article (“ Open Government or Legal Loopholes?” Nov. 2020)

Courtesy of Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas.

Kelley Shannon, executive director of the Freedom of Information Foundation of Texas, recently told me in a video interview that the City of Fort Worth may have abused outdated Attorney General rulings to delay fulfilling open records requests. As the head of a nonprofit that monitors government compliance with the Texas Public Information Act, Shannon said Fort Worth recently came to her attention.

Because of this outdated ruling, cities that stated they were working on a skeleton crew did not have to fulfill open records requests, Shannon said.

“Fort Worth was one of the worst offenders,” Shannon said, referring to what her group documented as excessive abuses of the outdated AG ruling. “We had some surveys done, checking around and looking at major governments around the state. Fort Worth was still doing it up until February of this year.”

When her nonprofit requested a copy of Fort Worth’s policy on what constituted a skeleton crew, the city’s Secretary’s Office sought to block the release of that information.

“That was pretty ironic,” Shannon said.

Last week marked the 50th anniversary of the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the Defense Department study that chronicled the failed U.S. policy in Vietnam, in The New York Times.

Following the publication of the third installment, the Nixon administration obtained a restraining order that barred subsequent publications of the papers. That order was upheld by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, which prompted an appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. The highest court in the country agreed to hear New York Times Co. v. United States on June 26, 1971, and, in a 6-3 decision, the court dissolved the restraining order and allowed the Times to continue publishing.

The lead opinion stated, “Any system of prior restraints comes to this court bearing a heavy presumption against its constitutional validity [and] the government thus carries a heavy burden of showing justification for the imposition of such a restraint.”

That Supreme Court ruling is cited as nearly solidifying the right of the press to publish without interference from the government.

Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers while working as a U.S. military strategist in 1971, went on trial for espionage, conspiracy, and stealing government property in 1973. The charges were dismissed, partly because the Nixon administration illegally obtained some of the evidence used against Ellsberg. Now 90, Ellsberg lives in California’s Bay Area. His popular quote on patriotism partly explains what drove him to leak the Pentagon Papers 50 years ago.

“For an American to be patriotic is to be loyal to the principles of our Constitution and the First Amendment,” he said. “The truth is that the policies of the government are sometimes in conflict with that. In our country, patriotism should not be defined as obedience to an authority.”