Fort Worth’s police union has never been one to pass up a good misinformation campaign, which is probably one reason they gleefully opened a Parler account, the preferred app for conspiracy theorists and white supremacists, earlier this year (“Police Union Parler,” Jan 13).

The upcoming runoff election on Sat, Jun 5, has the deep-pocketed Fort Worth Police Officers’ Association (FWPOA) once again peddling lies and fear-mongering with the goal of consolidating their stranglehold over Fort Worth City Council and lucrative city-funded pensions.

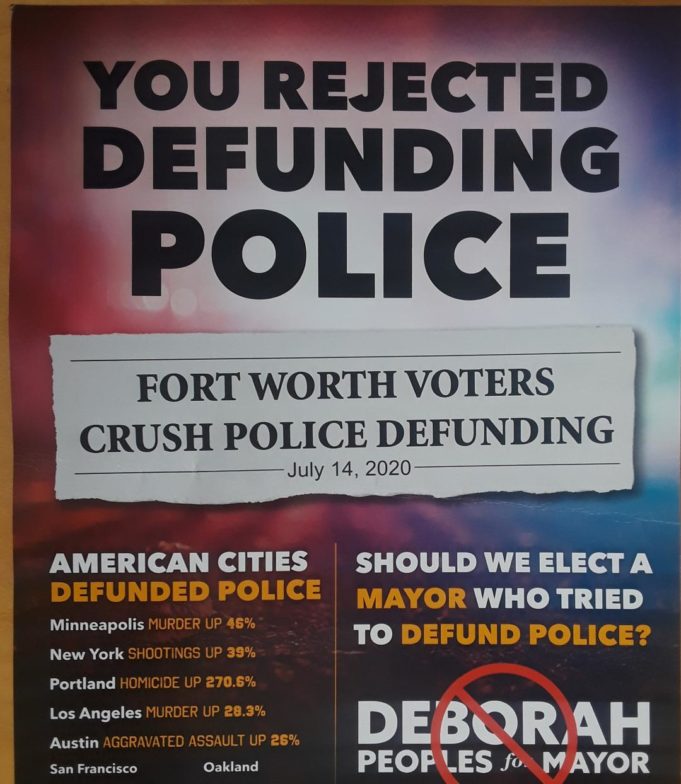

“Fort Worth Voters Crush Police Defunding,” reads the fictitious newspaper-esque headline of a recent police union mailer that urges Fort Worthians to vote for mayoral candidate Mattie Parker, the former chief of staff for the mayor and city council who has been endorsed by the police union.

The fake headline refers to the mid-2020 vote to renew Fort Worth police department’s Crime Control and Prevention District (CCPD), the discretionary fund that adds around $85 million every year through a half-cent tax to the police department’s $272 million annual budget. In 2014, 84.6% of voters chose to renew the CCPD. Last year, after a grassroots and largely nonpartisan public awareness campaign leading up to the July vote, 64% of locals voted in favor of renewing the fund. That’s quite a drop.

Recent FWPOA campaign ads play off the false narrative that progressive-minded candidates are dead set on abolishing all forms of law enforcement and that anarchy lite will follow. For their part, left-leaning candidates have been clear that economic and social justice must be included in policy making decisions over police budgets and other city expenses.

“What makes me so sad about the Mattie Parker and police association mailer is that it is a classic dog whistle against people of color and candidates for change,” said Parker’s opponent, Deborah Peoples, on Facebook in response to the deluge of police union flyers that are hitting mailboxes this week.

Behind the political posturing is a very real increase in shootings in Fort Worth and across the country. Murder rates in Fort Worth have increased between 2019 and 2020 by 60%, according to Fort Worth police. Marking a 20-year high, more than 19,000 were people killed in shootings and firearm-related incidents last year, according to Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit that tracks gun violence in the United States.

Historically, those deaths have disproportionately fallen on Black and brown communities. Black Americans experience 10 times the rate of gun homicides and three times the rate of fatal police shootings of white Americans, according to Everytown for Gun Safety, a nonprofit that advocates for stricter gun laws.

A February scholarly article published by researchers from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University examined the link between firearm violence, systemic racism, and the recent economic downtown that disproportionately affected poor communities across the United States. Using data from the Philadelphia Police registry, the researchers found that weekly shootings nearly doubled following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In the city of Philadelphia, shootings are often geographically concentrated in lower-income communities,” said Dr. Jessica Beard, lead author of the study. “These communities have not only been disproportionately affected by the coronavirus disease itself, but the pandemic and its associated policies have also exacerbated issues that were already present, including unemployment, poverty, structural racism, and place-based economic disinvestment, which are empirically tied to firearm violence in Philadelphia.”

The findings mirror Everytown for Gun Safety’s stance that “gun homicides, assaults, and police shootings are disproportionately prevalent in historically underfunded neighborhoods and cities. This lack of funding intensifies our country’s long-standing racial inequities.”

FWPOA seeks to link gun violence with efforts to “defund” the police.

“Defunded cities are now paying a heavy price with an explosion of crime,” one recent Fort Worth police union flyer reads.

At the top of the FWPOA list of 13 cities that allegedly defunded their police department is Minneapolis, where calls for police reform following the May 2020 murder of a Black man, George Floyd, by a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, were answered by a city council pledge to disband and reconstitute the city’s police department. One year later, that pledge has not been fulfilled as city leaders seek a piecemeal approach to law enforcement reforms.

Other cities that FWPOA list as having defunded their police department include New York City, which shifted $1 billion from the NYPD following a $9 billion revenue shortfall last year. FWPOA singled out Austin on its list of cities that allegedly caused a surge in violent crime by reallocating police department funds. Last year, Austin City Council voted to remove $150 million from the city’s police budget, although roughly $130 million was simply transferred to city groups and nonprofits that serve similar services as the Austin police department.

Missing from FWPOA’s flyers is an acknowledgment that local Black and brown communities have been actively defunded for decades. You only need to drive through the Eastside neighborhoods of Stop Six or Polytechnic Heights to see the disparity in public and private services that leave those communities devoid of access to healthy food and other basic services.

The FWPOA is betting that they can reach enough uninformed or willfully ignorant voters to maintain political sway over an ever-younger and increasingly progressive voter base that understands the causal relationship between economic inequality and crime. As long as Fort Worth police department’s budget gobbles one-third of the city’s general budget, spending on law enforcement should remain part of a broader discussion on how city services can be better allocated to reverse decades of disinvestment in Fort Worth’s historically underserved communities.