On Sunday, Mar 28, more than 100 members of the North Texas Burmese community gathered outside the Fort Worth Convention Center to raise awareness about the military coup and subsequent political violence in their home country, Myanmar. Similar protests and rallies have occurred across the United States, including outside the State Capitol in Austin the day before.

“We’re here to show that we are not in support of the military coup, which has resulted in a lot of people killed in Burma,” Tin Khamh said. A member of the DFW Myanmar Ethnic Community group, which formed in February in response to the military coup, Khamh said their aim is to show support for those seeking an end to military rule in Myanmar.

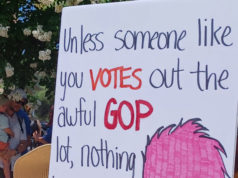

The group marched from the Convention Center to the Tarrant County Courthouse, bearing signs and chanting in both English and their native tongue. “Shame on the Chinese government! Shame on the Russian government!,” the crowd chanted, referencing the sale of Chinese and Russian weapons to the military regime.

Individuals from various Myanmar ethnicities were represented at the rally, some wearing folk garb specific to their ethnic communities. They were joined by Saginaw City Manager Gabe Reaume, who spoke to the crowd about his fondness for the country after visiting it as a U.S. State Department Fellow two years ago.

Myanmar, also known as Burma, has a complex political history that has been marked by instability since gaining independence from Britain in 1948. Though initially established as a democracy, the country underwent a military coup in 1962 and was effectively governed by a military junta for the remainder of the 20th century. A new constitution in 2008 paved the way for a transition to democracy that began in 2011, which resulted in several electoral victories for pro-democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi’s party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), in 2012 and 2015.

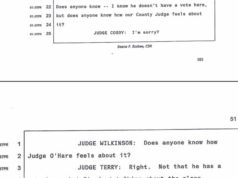

In 2020, the NLD won a landslide victory, winning 396 out of 476 elected seats in parliament. The aftermath of the election was fraught with allegations of fraud, with many smaller parties of varying political affiliations contesting the vote. The primary complaints came from the military and its proxy party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party, but, ultimately, international election observers and Myanmar’s Union Election Commission dismissed the claims for lack of sufficient evidence. Despite the affirmation of the election, military leaders continued to allege fraud and promised to “take action” if their complaints were not addressed.

On Feb 1, the military kept their promise by detaining Aung San Suu Kyi and other members of the ruling NLD party. The next day, the military established the military junta known as the State Administration Council. In the subsequent months, police have raided the NLD headquarters and arrested a large number of government ministers and activists.

A civil disobedience movement known as the Spring Revolution emerged in response to the imposition of military rule. The movement has attracted hundreds of thousands across Myanmar to participate in various acts of protest, labor strikes, and boycotts against the military regime.

In mid-March, the regime instituted martial law after a deadly weekend of protests in which approximately 50 people were killed by military and police forces. As of Mar 28, at least 3,070 protesters have been detained and at least 423 have been killed by Myanmar security forces.

These events have come as a shock to members of the North Texas Burmese community, who struggle to keep in touch with their relatives in Myanmar amid the internet and social media blackouts imposed by the military leaders.

Many at the protest told me that they are concerned for the safety of their relatives, particularly those who have been involved in pro-democracy movements.

“My dad was involved in the pro-democracy movement in 1988, so I’m constantly concerned if they will be taking him in or anything,” Lin Lin said.

Some told us that they have lost touch with some of their relatives in Myanmar following the military coup.

“One of my brothers is an elected representative from the National League for Democracy,” Su Htwe said. “I cannot get in contact with him.”

Though many at the rally in Fort Worth wore shirts or held signs in support of Aung San Suu Kyi, the leader of the NLD, not all participants see the events as partisan.

“While the NLD may be seen by many as a pillar of democracy for Myanmar people,” Judson Lynn said, “the truth behind our protest and the civil disobedience movement is that it’s not for a particular party but for democracy and for freedom for the whole country. To have elected government by the people and for the people.”

According to the independent news outlet Myanmar Now, at least 114 civilians were killed by security forces in 44 towns across Myanmar on Mar 27, marking the bloodiest day of protests to date. Embassies from the United States, European Union, and United Kingdom have all condemned the killings.

Organizers with the DFW Myanmar Ethnic Community say they will continue to organize rallies to draw attention to the ongoing violence. — Steven Monacelli