Three journalists have teamed together to analyze the abduction and murder of seven young women in the mid-1980s. In their podcast still …, they dive into seven cold cases that span from 1983 to 1985, all closely related and occurring in North Texas. The team believes these murders to be the work of one serial killer.

Host Gary Anderson is the voice of the podcast, while his wife Karin Anderson and her former colleague Kristine Hughes spearhead the investigation. The three are all former journalists who changed career paths and are thrilled to be back in the industry, practicing their passion. They refer to themselves collectively as The Reporter’s Notebook.

During this three-and-a-half-year time period, approximately two dozen cases occurred in the Fort Worth area, consisting mostly of the abduction, rape, and murder of women. The team chose these seven cold cases to be their focus because they were closely related and did not fit the demographic of the other killings, which appeared to include prostitutes and other criminal activity.

Before leaving the newspaper industry, Karin and Hughes were former reporters for the Dallas Morning News. In 2017, they discussed the possibility of working on a project together that would bring them back to their journalism roots. Three years later, they decided to take that step and focus on cold case Fort Worth-based murders.

Hughes was around the same age of the victims and remembers living in Dallas during the murder spree.

“I recall hearing about it,” she said, “particularly the TCU homicide, and how girls that were going to college were being very careful, especially in parking lots at night, but it didn’t stop me from going to nightclubs and hanging out with my friends.”

Gary was merely a year and a half away from graduating from Grand Prairie High School and attending the University of Texas at Arlington, where one of the victims was attending when she was murdered.

“It is really fascinating to me from a personal point of view, going, ‘My gosh, we lived through this, and I had no idea,’ ” he said.

The trio hope that by talking about what happened, someone listening will remember seeing or hearing something and will contact the police. Someone may have a clue that is needed to bring closure to one of these unsolved crimes.

*****

The trio’s research revealed that during the mid-1980s, six serial killers were operating in North Texas.

“These two dozen murders prompted the formation of a task force in Fort Worth,” Gary said, speaking to me recently along with Karin and Hughes from the Andersons’ home in Garland and Hughes’ home in Alabama.

“Though each of those murderers are now either dead or incarcerated,” Karin added, “police aren’t certain that all of the victims have been identified. They could only identify the ones that they were able to link through DNA or confessions.”

An advantage that these reporters have over the police is being able to step back and observe all of the evidence and information through an objective lens.

In the first episode of still … that aired in late January, the hosts discuss the murders out of chronological order. The first murder was a cold case from August 1983. Twenty-seven-year-old Mary Till left her apartment in Arlington around 9 a.m. and headed toward her workplace at a downtown Dallas law firm. She didn’t arrive for work that morning, and her car was found 10 miles from the office with the interior burnt. Five months later, her body was found in a field not far from her car. She had been shot in the head.

The way Gary narrates the podcast is ominous. He brings intrigue, as if you are listening to a scary bedtime story on the edge of your seat, wanting to catch every last detail. Satisfyingly, he provides them in depth. The podcast holds more interest than a mere retelling of each gruesome murder. The journalists did extensive research in taking on the private investigation.

The second murder took place in November of the same year. Sandra Bush, 21, left her southeast Fort Worth home at 6:45 p.m. without telling her family where she was going. Her car was found outside a bar on the North Side, wiped clean of fingerprints, with a bloody pillowcase in the backseat. Her body was discovered months later in a field near her car. She had been strangled.

What brings the podcasts to life is the commentary by family and friends of the victims, as well as police officers who worked their case. still … brings a unique perspective to each podcast by personalizing the victims’ stories, looking not only at all the facts but also into the prolonged effects of these life-changing tragedies.

In September 1984, 23-year-old Catherine Davis returned to her apartment in southwest Fort Worth around midnight. Neighbors heard angry voices and witnessed a man shut the door to her apartment and leave in her car. Just hours later, her home was engulfed in flames. Her vehicle was found after several days, just a few miles away. Coat hangers with human blood were found inside her car, and blood was smudged on the door handle. Davis’ body was found less than seven miles from her apartment.

Less than a month after Davis’ murder, 23-year-old Cindy Heller disappeared after assisting a stranded female driver in southwest Fort Worth. Heller left a note on the door of the driver’s friend’s apartment, trying to help them get in contact with each other. Months later, Heller’s body was found nude in a pond on the TCU campus. She had been strangled.

A listener who grew up in North Texas called in after hearing the podcast and explained why a lot of the young women at that time were not familiar with or precautioned about the serial killings. The caller said even though she was aware of what was going on around her, a lot of people weren’t because media wasn’t the same then as it is now. There was no social media, so news wasn’t immediately distributed. If you didn’t subscribe to the newspaper or watch the evening news, you were in the dark about the murders.

“Most of the people in the age bracket of these victims probably weren’t familiar with what was going on because they weren’t the demographic that was subscribing to the newspaper or watching the news,” Karin said.

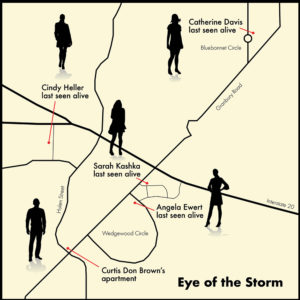

“Four cases were concentrated not only in space, but they were concentrated between September and December of ’84, all within a two-mile radius,” Gary said.

That December, 21-year-old Angela Ewert stopped at a convenience store after leaving her fiancé’s house in southwest Fort Worth around 11 p.m. She headed east, but several miles down the road, she pulled over with a flat tire, which appeared to have been stabbed. Her body wasn’t found until 1993 in a field in south Tarrant County. Her purse was located in a pond in southwest Fort Worth, close to where Heller’s body was discovered.

“The ones that are most closely linked were all in the southwest Fort Worth area,” Karin said. “Two of them were definitely from the Wedgwood area, and two more were closer to Hulen and TCU. There are a couple of others … but, you know, at some point, we had to cut it off and say we can only really fully investigate this many cases and still make it understandable for our listeners.”

“In 1985,” Karin said, “the Fort Worth Police Department opened a task force because there were so many murders and abductions happening of women that they needed a team of at least 35 investigators to focus on these cases.”

One of the things that the task force was initially looking at was the strange coincidence of how so many of these victims, including some that were not among the seven, were involved in one way or another to the fashion modeling industry. Though all the victims were young and attractive, the investigators decided that information was merely coincidental.

“If somebody is hunting young, attractive women in this area, odds are pretty good that they may have been involved in modeling in some way or another in the mid-1980s,” Karin said.

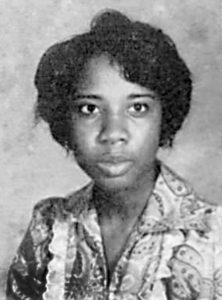

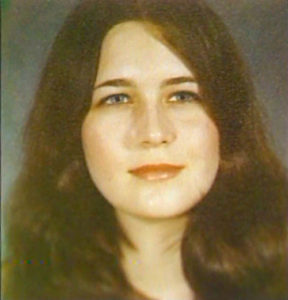

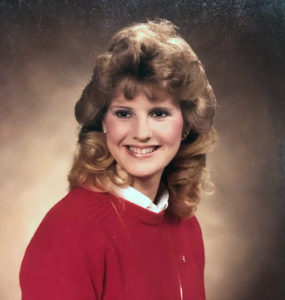

According to the investigative journalist, the physical characteristics of the victims widened across a spectrum, varying in hair color, height, and even race. One of the victims was African American, but the others were all Caucasian women.

The Reporter’s Notebook, Hughes said, wants to “keep the victims’ names and memories out there in hopes that something comes up that the police don’t know about yet. I don’t think our goal is to solve, because I think that would be arrogant, but just to shed light on it so that the families could get some kind of satisfaction from it, kind of a feeling of closure. Even if it’s not true closure, it’s a sense of closure.”

The most challenging aspect of their podcast was finding someone who knew the victim. “It’s a heart-wrenching moment to make a cold call to somebody when you don’t know how they’re going to react,” Karin said, “hearing you asking them about a murder that happened 35 years ago … the murdered being someone that they love. Though it’s a difficult thing to do, it’s also very fulfilling because a lot of times, people really love the opportunity to share the good memories and they don’t want their loved one to be remembered for the horrible way that she died. They want her to be remembered for who she was.”

Gary recalls that the hardest connection made was with a sister of the victim. After hearing from her voicemail how offended she was by the team’s call, it made them question if they were doing the right thing. The worst example was outweighed by another victim’s sister, who couldn’t have been more open.

“She’s been gracious, kind, and so thankful and grateful,” Gary said. “She couldn’t believe that after 35 years, somebody still cares about her sister’s death.”

The sixth victim who was analyzed was 15-year-old Sarah Kashka in late December of 1984. After being dropped off by her date, intending to visit a friend in southwest Fort Worth, she was last seen walking across the street to a Dairy Queen. Her body was found a few days later in a creek in southwest Dallas, stabbed to death.

“I think that this man felt power by stealing the lives of beautiful women,” Karin said. “I think that gave him a sense of omnipotence and that he could do anything he wanted if he could steal the young beautiful women off of the street and kill them.”

The seventh victim is Terri McAdams. She arrived at her fiancé’s apartment in Arlington around 6:30 p.m. on the eve of Valentine’s Day in 1985 and was expected to pick him up from the airport the following day. Around 10:30 p.m., an intruder broke in, raped her, and beat her to death.

“We believe throughout the course of our podcasts and our investigation that it’s very likely that one man committed at least seven of the murders,” Gary said.

“Having the benefit of hindsight 35 years later,” Karin said, “we’re able to take all the things that were reported at the time and point out what appeared to be relevant and what police later dismissed as being just mere coincidence. We looked at the patterns of this particular man and compare them to these crimes, but I don’t want to say that we were the first person to say we think he committed these crimes. We saw newspaper reports where police had identified him as the primary suspect. It’s not like we solved the case of the century, and we don’t know that it’s been solved at all, but we were just following up and exploring further what had been kind of left behind.”

*****

Using public data to view his background, the team discovered that the man they believe to be the killer, Curtis Don Brown, was arrested on May 29, 1986. The previous day, he had broken into a woman’s apartment and dragged her out into a field, raped her, and bludgeoned her to death. They believe he was leaving the scene of the crime with two of her purses when he was noticed by police, who were staking out the area on an unrelated matter. When they tried to stop him to question him, he ran but was apprehended and arrested after a fierce struggle. When they looked inside the purses, officials found the woman’s ID, so they went to her apartment. Police saw that there had been a struggle there and began searching for her. She was found lying in the field. He was quickly charged with murder.

In tracking Brown’s history, the team discovered he had been previously convicted of an unrelated felony and was released from prison in 1983. Upon his release, he moved back to Fort Worth.

“We tracked where he was living at the time in relation to where the victims were taken, and he had ties to every single one of their locations in one way or another,” Karin said. “He lived very close, within a mile to where these women were being taken from or where they were being dumped or where their car was found. It was like you could just draw a map to him every single time.”

They had been working on this podcast since last July when they reached out to interview Brown in prison. They could not go any further because media aren’t allowed to interview prisoners via video or telephone. It had to be in person, which wasn’t an option because of COVID. After reaching out to him through the JPay system’s email, there was no response.

“There is a way where you can track prisoners online,” Gary said. “Punch in their information and see where they are. We watched over four or five months, and he was transferred no fewer than two times, probably because of COVID or because he was dying.”

When they checked in on him again on February 5, the journalists were shocked to discover that he had died the previous week.

“A strange twist was that the date of his death coincided with the release of the podcast’s first episode,” Gary said. “It upsets us deeply that someone who may have held the answers to so many questions took his secrets to the grave. We pray that his death doesn’t mean an end to hope for the victims’ families or prevent police investigators from seeking DNA proof that could either clear him in these cases or confirm our suspicions. Regardless, our pursuit of the truth has not come to an end.”

After incarceration, Brown was linked to additional murders.

“Arlington police got a match for one of their unsolved cases, so that’s how he got convicted for three murders before he died in prison this year,” Gary said.

The team believed Brown went unnoticed in 1985 because of his race.

“We want to note that African American serial killers are not rare,” Karin said. “They just didn’t get the attention from the FBI, so they didn’t get the attention from Hollywood. Every time you see a serial killer depicted, essentially, it’s a white male. This myth kind of got perpetuated through the years about who serial killers are.”

“A lot of it goes back to when the FBI started its Behavioral Science Unit,” Gary said. “They were trying to get funding from Congress. One way to do that was to do a media tour and talk about figuring out the mind of a serial killer. They essentially created a profile of what makes a serial killer, and they said it’s going to be a white man. It was born out of that, and it has just persisted for the last 30 to 40 years because of mainstream media, movies, TV shows, and books. … Nobody paid attention to the fact that it didn’t matter what race you were. Serial killers were evil. Evil is evil, and it didn’t matter at all when it came to race. …. We appreciate the story getting out because our work and our goal is better served the more listeners that we have.”

“We need listeners to get involved,” Karin added. “We need their thoughts and their theories. If somebody saw something or heard something, or remembers something, it could be a lot more significant than they realize, and so the more people that engage with us, the better off everyone’s going to be and the better off the odds will be that police will be able to finally close these cases.”

All the police knew was that each of the missing women had been in their cars and were somehow taken.

Anyone with any information pertaining to the murders discussed should contact the Fort Worth Police Department’s cold case unit at Now that this part of is finished, The Reporter’s Notebook is already working on its next project. All of their ideas are related to criminal investigations.

Through poring over spreadsheets, searching old newspaper clippings, listening to TV news reports, and conducting good old-fashioned investigative journalism, still … is in-depth and enthralling. The podcast focuses on finding peace of mind for those affected by the violent crimes.

“More than 35 years later,” Gary said, “the victims’ families and friends are still waiting for answers, still waiting for justice, still waiting for peace.”

A very intriguing article. Sometimes it takes eyes and interests other than the law enforcement to make connections. Our law enforcers see death and evil everyday and sometimes that numbs them to actual or possible facts. What a great service y’all provided for young (and even older) women in the TX community. I should say every community because evil seems to be everywhere. Thank you for your keen work.

I did call the police and they never checked out what I told them.

What is Curtis Don Brown’s date of death and cause of death?

I was a Freshman at TCU in ‘84-‘85. We returned from Christmas break and were handed the key to our dorm room and a “briefing” from the college about the missing co-eds and the dismembered body found on campus. They started an escort service for anyone with a night class who wanted someone to walk them to class. It was terrifying.

PLEASE ask them to do a report on the Austin Yogurt Shop Murders. It will bev30 years this year, on December 6, and it is still unsolved.