After years of being plagued by accusations of public corruption, Ellis County has a new district attorney and the opportunity to put a troubled office back in order. This week, DA Ann Montgomery replaced former DA Patrick Wilson, who did not seek reelection and is leaving the criminal law profession entirely.

A 2018 lawsuit sought to remove Wilson from his elected position for acts of misconduct and for allegedly committing at least four felonies.

Wilson committed a “state jail felony” when he obtained emails from a secure county server, according to court documents. Constable Mike Jones was the target of the email collection.

“Patrick Wilson acted with the intent to harm Constable Jones by invading his private communications and then attempting to use those private communications to criminally prosecute Constable Jones,” court documents read.

An Ellis County judge dismissed the case without a hearing or explanation.

In July 2018, Dan Gus, the attorney who filed the lawsuit, told The Texas Monitor, a government watchdog blog, that “it’s certainly frustrating when you make credible, serious allegations of felony conduct by the district attorney’s office and a judge rules without explanation and without any hearing.”

Wilson did not respond to requests for comment. Wilson avoided being forced from office but announced in early 2019 that he would not seek reelection once his four-year term expired on Dec. 31, 2020. One political insider who asked to not be named believes Wilson chose to leave office voluntarily rather than lose a reelection bid.

Reports of high-ranking elected officials committing potentially criminal acts have become a common occurrence. The next U.S. Attorney General may decide whether to charge President Donald Trump with a range of criminal acts that could include obstruction of justice (as laid out by Robert Mueller’s investigation), bribery (for withholding aid from Ukraine in return for political favors), and campaign finance violations (for actions that landed Trump’s former attorney, Michael Cohen, in jail), among many others. Many Constitutional scholars believe that Trump — or Vice President Mike Pence, if Trump intentionally resigns before his term ends — could issue a blanket pardon for the entire Trump family, especially son-in-law Jared Kushner for omitting more than 100 foreign contacts when he applied for top-secret clearance or for Donald Trump Jr.’s campaign finance violations when he met with a Russian lawyer in 2016 to obtain potential dirt on Hillary Clinton.

Democrat Robert Brady, former Representative for Pennsylvania’s 1st District, did not seek reelection two years ago after allegations of a criminal conspiracy to hide a $90,000 payment were made public. Brady avoided criminal charges. In early 2017, a special prosecutor cleared Tarrant County District Attorney (TCDA) Sharen Wilson of criminal intent for actions she took the year prior when she solicited campaign contributions from government employees. The Texas Penal Code forbids public servants from using their positions for nongovernmental (i.e., fundraising) purposes.

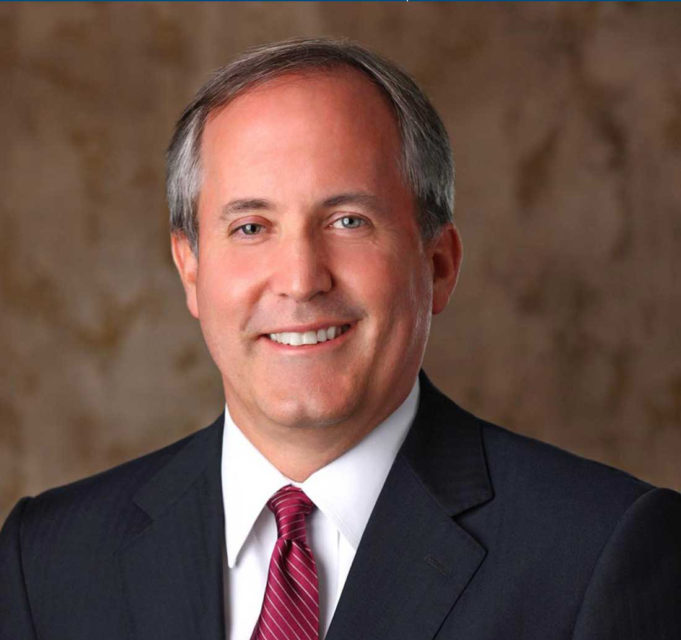

And Ken Paxton, Texas’ top law enforcement officer who is currently indicted on three felony charges related to securities fraud, is facing a new lawsuit that alleges that the state AG engaged in whistleblower retaliation, and the FBI is investigating accusations that Paxton committed bribery, abuse of office, and other crimes aimed at aiding Nate Paul, a past donor to Paxton’s reelection campaign.

Elected officials and law enforcement officers are rarely held accountable for unethical or criminal behavior. Documents obtained by the Weekly through open records requests show that law enforcement agencies and news publications, as recently as this past summer, have alerted the attorney general’s office about unethical or potentially criminal acts committed by several district attorneys. One 2011 letter from the attorney general’s office shows that the AG dismissed concerns raised by an Upsher County sheriff without explaining why the case would not be examined. The sheriff described actions taken by Upsher County DA Billy Byrd (who still holds that office) to infiltrate a secure computer system managed by the sheriff’s office. Those actions, Sheriff Anthony Betterton warned, gave Byrd the ability to “add, delete, and modify” the criminal records system at will.

“I do not believe that the allegations detailed in your letter constitute criminal violations of Texas statutes,” an AG director replied. “Therefore, this office will take no further action regarding your request for assistance.”

A July 30, 2020 document obtained through an open records request describes threatening behavior by Freestone County District Attorney Brian Evans.

“Mr. Evans is accused of entering the Freestone County Times newspaper office, throwing a chair at employee Victoria Keng, and using threatening language toward Ms. Keng,” read the document from the AG Law Enforcement Division. Fairfield City Administrator Nathaniel Smith “said the newspaper had published articles that were critical of Mr. Evans. Mr. Smith asked the Texas Rangers to investigate the scene but were told by Lt. Thomas of the Waco Ranger office to contact the Office of the Attorney General for assistance.”

In a letter posted July 30, Smith and Fairfield police chief David Utsey described the need for an outside investigation.

“The Fairfield Police Department cannot investigate this complaint due to a conflict of interest involving Mr. Evans,” the letter read.

Photo courtesy of Ellis County

District attorney offices work closely with city police departments and other peace officers. The relationship is one of co-dependence: Detectives gather evidence, and district attorneys (or their legal staff) represent the state when prosecuting crimes based on the evidence once the DA accepts the charges. One half of the criminal justice system could not function without the other. In a police statement, Keng described the incident and made no mention of a chair being thrown at her, contrary to the AG document.

“Brian Evans knocked on the office doors at Freestone County Times,” Keng wrote. “I opened the door. He walked in, and I said, ‘I am the only one here’ as he walked toward the back. He grabbed an office chair and flung it. Then, he spun around and said, ‘You know this shit is wrong, don’t you?’ I repeated, ‘I am the only one here.’ As he left, he said, ‘Tell him to be here tomorrow.’ Then he left.”

On Aug. 3, Smith again contacted the AG’s Law Enforcement Division and was told that “the request for investigation had been received and is under review by the special investigations group,” according to an AG document. The AG’s office did not respond for comment on the investigation, which is likely ongoing. Evans also did not respond to a request for comment.

The grounds for removing a district attorney are laid out in Texas Local Government Code Section 87.012, which states that district attorneys and other officers can be removed for official misconduct, incompetency, or intoxication. Since 2017, around 800 investigations into public official misconduct have been conducted by the Texas Rangers through the law enforcement agency’s Public Corruption and Public Integrity units. Records released by that agency to the Weekly reveal a wide range of public official misconduct, from bribery and abuse of office to money laundering and fraud. A Rangers spokesperson would not say how many elected officials have been removed from office or have faced prosecution as the result of the investigations.

One commonly used system for investigating allegations of criminal acts committed by public officials involves appointing an attorney pro tem to inquire into the case, but those efforts rarely hold public officials accountable and often rely on investigators filing criminal charges on colleagues or personal friends. The number of attorney pro tems appointed by the TCDA’s office is on the rise: 2016 (2), 2017 (3), 2018 (6), 2019 (5), and 2020 (7). Nine of those investigations were authorized by Tarrant County Judge George Gallagher, according to the county.

“Tarrant County is hiring these people and giving them money, and they are not doing” their job, said Keith Lane, former Haltom City chief of police. When serving as Haltom City city manager more than two years ago, Lane said he witnessed a Tarrant County system that blithely ignores public misconduct.

*****

Soon after taking office as city manager in 2016, Lane alleges that he witnessed numerous violations of city ordinances, the Texas Open Meetings Act, and numerous government codes. After years of observing what he said was flagrant disregard for rules and laws on the part of a handful of city councilmembers, Lane reported the incidents to the Texas Rangers and the Tarrant County DA in May 2018.

One former city councilmember had it out for a firefighter who was a member of an influential political action committee, Lane claims. The councilmember allegedly spoke about the firefighter during a closed executive session that April, which amounted to a violation of the Texas Open Meetings Act. The firefighter was not notified of the meeting and was not present to defend himself against the accusations levied by the elected official, Lane said, adding that he told the police chief to hand-deliver the evidence to the DA and the Rangers.

As Lane waited to hear back from the district attorney’s office, he claims he continued to observe “complete and total violations” of local government codes and the open meetings act. Violations of the code in question could lead to a fine of $100 to $500 and/or confinement in the county jail from one to six months.

On June 13, 2018, Judge Gallagher assigned Leon Haley Jr., a local criminal defense lawyer, as Tarrant County criminal district attorney pro tem in the matter of “meetings and transactions involving officials of Haltom City.” Tarrant County DA Wilson had requested to be recused of the matter, according to court documents. Recusals are often permitted to avoid conflicts of interest, but the specific reason for Wilson’s request is not described in the court documents. The investigation was subsequently passed to retired Fort Worth police officer Joe Kalbfleisch and criminal trial attorney Miles Brissette, according to an April 2019 letter from the DA’s office.

As Lane claims he waited for Kalbfleisch and Brissette to take action, work for him became almost unbearably stressful. He continued to work with the same elected officials whose names were now in the hands of the DA. After waiting months for any sort of response from the DA, Lane reached out to the state attorney general’s office.

“They have a hotline for violations of the open records code,” he said. “I told [the official who answered the phone] about what I’d turned into the DA’s office. He said, ‘Send your documentation to their special crimes unit.’ I wrote a letter to the attorney general that July. I sent supporting documentation with it. I never to this day have heard back from the attorney general’s office.”

With 10 years of experience writing reports as a detective, Lane believes that the inaction on the part of the attorney general and DA has nothing to do with the credibility and meticulous documentation of his reports. Beyond providing what he described as substantial evidence, he said both the DA and AG offices have the names of numerous credible witnesses. Lane claims the only action taken by attorney pro tem Brissette and investigator Kalbfleisch was a brief visit to Haltom City’s city hall building in 2019. The appointed investigators allegedly filed a subpoena for 3,000 documents that could have been obtained through an open records request, Lane said. Lawyers can bill for filing subpoenas while an open records request would not have cost Tarrant County anything, Lane said.

The attorney is probably making a lucrative hourly rate, he said. “They haven’t spent 10 seconds talking with me.”

Kalbfleisch and Brissette did not respond to my requests for comment. The TCDA’s office did not provide requested information on how special prosecutors are compensated by the county.

Lane contrasted the two and a half years of Kalbfleisch and Brissette’s investigation (if it is still ongoing) with a six-month inquiry by the Texas Ethics Commission (TEC) that resulted in a $5,000 fine against Concerned Taxpayers of Haltom City, a political action committee. The elected officials and former elected officials who were ultimately fined did not include a political advertising disclosure statement on flyers that were sent to Haltom City residents to encourage them to vote against two 2018 bond measures, according to TEC documents.

As police chief several years ago, Lane said, his relationship with DA Wilson was cordial but became decidedly less friendly as the two began disagreeing over a range of issues related to policing policies and how cases are prosecuted.

“They think that if they stretch this out long enough, I will eventually retire and move on,” he said. “They want to see this investigation have a slow death.”

*****

Transparency and accountability go hand in hand, and both are often lacking in Texas. The Weekly’s open records request that sought copies of complaints against all Texas district attorneys over the past 10 years came back with a scant 14 pages of documents. Public information can be withheld if there is a pending investigation or something as seemingly benign as a date of birth listed. The AG’s office included a letter to appeal our open records request, but with no reference to withheld information, it’s impossible to know what we can appeal.

Photo courtesy of Facebook

As with many Texas cities, Fort Worth city staffers have codified legal loopholes that work against public accountability and transparency. Local administrative regulations are designed to cull city communications on a regular basis.

“Users must delete emails from all mailboxes as soon as they have been read and/or as a matter of regular and proactive maintenance,” city regulations state. “Much of the content or even informational city email is subject to release and publication” through the Texas Public Information Act.

Policies at the Fort Worth police department and TCDA’s office similarly require that emails from retired staffers are deleted. A recent request by members of the grassroots group No Sleep Until Justice for a list of all offenses committed by active Fort Worth police officers was met with a nearly $1,800 bill after the city failed to block the request by seeking a legal brief from the AG (“ Public Disservice?” Nov. 2020). Legal briefs often allow the city to withhold important publication through Public Information Act caveats. The fee was levied despite the compelling public interest in the request.

“If a governmental body determines that producing the information requested is in the ‘public interest’ because it will primarily benefit the general public, the governmental body shall waive or reduce the charges,” reads one Texas open records policy.

A 2019 article by ABC News (with collaborative reporting from the Houston Chronicle) found that, once an open records request was sent to the state AG, the requested information was released 5.4% of the time in 2018. One blanket excuse for withholding important public information — stating that the release would compromise an investigation — is effective 98% of the time, the collaborative reporting found.

The Fort Worth Secretary’s Office, which handles open records requests, described the process of seeking a legal brief.

“The Public Information Act sets out certain exceptions to public disclosure,” the secretary’s office said in an email. “When a departmental liaison reviews documents that are responsive to a request, that person is tasked with identifying whether the information contains a statutory exception to disclosure. If the departmental liaison determines that the responsive records contain information that may be excepted from disclosure, then that person sends the records to the legal department for review. If the legal department agrees with the department’s assessment that certain information meets one or more of the statutory exceptions to disclosure, then the legal department will prepare and send a brief to the attorney general requesting that the information be withheld from public disclosure per the Public Information Act.”

Even when information can be withheld, that does not mean that the city (or any governmental body) is compelled to seek a legal brief, nor is the city compelled to levy fines as a requirement of fulfilling the Public Information Act. Those fines and delay tactics unevenly fall on requests that seek public accountability of public or elected officials.

In the fall, the AG ruled that the request for a ledger of officer offenses had to be released. The 37-page ledger includes documented infractions by officers. Assault, “criminal violation,” weapon violation, theft, and sexual assault are some of the more egregious infractions committed by currently active Fort Worth police officers.

Fort Worth Police Officers Association president Manny Ramirez said the list is proof that Fort Worth officers are held accountable for their actions.

“It’s a big list,” he said. “What it shows is that we don’t sweep things under the rug. [Every incident] is investigated, and officers are disciplined. Fort Worth police department does a good job of holding people accountable.”

In late 2019, Fort Worth City Council gutted the Ethics Review Commission (ERC) (“ Ethics Review? What Ethics Review?” Nov. 2019). All but one councilmember, Ann Zadeh, voted in favor of abolishing the volunteer group responsible for enforcing the city’s ethics policy. At the time, city staffers said it was difficult keeping members active. The ERC was replaced with a business-friendly enforcement body that pulls volunteers from standing city commissions as needed.

*****

In a state that rarely investigates or prosecutes misconduct by government officials, disbarment may be the only reliable remedy for removing incompetent or malicious prosecutors from courtrooms. In 2015, the DA at a Central Texas county called Burleson, Charles Sebesta, was disbarred for prosecuting the case of an innocent man, Anthony Graves, who sat on death row for more than a dozen years before being exonerated after the release of DNA evidence.

In a six-page ruling issued by the state bar’s disciplinary panel, Sebesta was found to have hidden evidence, presented false testimony to the jury, made false statements, and engaged in fraud during the Graves case. Senate Bill 825, passed in 2013, extends the statute of limitation for disciplining state lawyers who suppress evidence. The four-year statute of limitation is reset when a falsely imprisoned individual is exonerated. The Michael Morton Act, named after the wrongfully convicted Morton and passed during the same legislative session, requires prosecutors to make certain types of evidence available to defense lawyers.

“We aren’t going to let the prosecutor off the hook for mistakes and errors they could have prevented,” said State Rep. Senfronia Thompson, who sponsored SB 825 and the Michael Morton Act.

Lane retired from his position as city manager one year ago and is the current interim police chief in New Braunfels, Texas. His whistleblowing and reporting of unethical behavior in Haltom City have posed challenges for him as he begins his new career. Each job interview comes with a long discussion on why he reported the actions of colleagues. His years in the highest positions of law enforcement didn’t prepare him for the roadblocks that he believes create a legal framework that allows elected officials to skirt laws and accountability.

“I think once you decide that you want to run for office in Tarrant County, you join a good-ol’-boy system,” he said. “They support each other. They have the mindset of needing to stick together. ‘If we stick together, we’ll get re-elected as many times as we want to.’ ”

“If I ran against [Tarrant County] Sheriff [Bill] Waybourn, I’m not going to win because I’m not a good ol’ boy,” Lane said. “I would not be accepted into that system.”

Given the political culture in Tarrant County, Lane has advice for anyone who observes or documents public misconduct or corruption.

“If you truly want this stuff investigated, you give it to the Texas Rangers,” he said. “The Texas Rangers are free and do not use taxpayer money. At the end of their investigation, they will turn in a report. There will be something in writing. It will say, ‘This is who we talked to.’ ”

Two and a half years after turning in evidence to the DA, Lane feels that the system of appointing a lawyer to investigate the matter was also an effort to keep the investigation out of the hands of the Texas Rangers. One letter by the DA to the Rangers is all it would have taken for the Rangers to investigate the matter in a timely manner, Lane believes.

Records provided by the Rangers show that, over the past three years, the Company B Rangers, who cover North Texas, completed 43 investigations. Nine investigations, including one in Tarrant County for “tampering with public records,” remain active. The Rangers’ office did not provide details on whether the 43 closed cases resulted in criminal charges being filed against government officials.

The special prosecutors assigned to Lane’s case ignored basic questions about their investigation, and the DA’s office ignored media requests for comment on whether the case was ongoing or closed.

In what amounts to a farewell speech, former Ellis County DA Patrick Wilson issued a lofty public statement about his exit from practicing law.

“I have long been open to them about my desire to explore a new path in life,” he wrote. “I am incredibly proud to have dedicated a career to seeking justice for others. But life is too short to spend it all in the darkness. I am excited about stepping into the light and enjoying the beauty of life with my family and friends. Until then, I will continue to lead my dedicated team of attorneys, investigators, and staff, to see that justice is done for our community.”

Patrick Wilson’s tone was decidedly different when he recently responded to a complaint I filed with his office.

He said, “Webster’s dictionary defines a conspiracy theory as ‘a theory that explains an event or set of circumstances as the result of a secret plot by unusually powerful conspirators.’ In my extensive professional experience, those who adhere to conspiracy theories are motivated not by a distrust of a logical narrative supported by objective facts. They are, instead, motivated by a dislike of the logical narrative and objective facts. A mere attempt to persuade a person otherwise is, for the person so convinced, proof of the conspiracy which resonates loudly in their personal echo chamber.”

Patrick Wilson did not explain what the supposed “conspiracy” was. His letter, written on Ellis County & District Attorney letterhead, was sent to me in response to my notarized complaint detailing an alleged conflict of interest that his office had overlooked or ignored. Judge Gallagher had assigned Ellis’ Wilson the duty of investigating misconduct in Tarrant County, based on government documents and evidence that led to the termination of assistant Tarrant County district attorney Alfredo Valverde last year.

Patrick Wilson assigned the case to an investigator who was allegedly friends with one of the individuals being investigated. That created a conflict of interest, I noted in my complaint, to which he replied: “My experience precludes me from the hopeful belief that this letter will cease your conspiratorial protestations. Please encourage whatever agencies to whom you are voicing your complaints to contact me at their convenience. I welcome the opportunity to speak with them. Be advised, however, this will be my only communication to you.”

One confidential source read the letter and noted that Patrick Wilson’s tone reflects a Texas office that is rarely held accountable for unethical behavior.

The letter, the source said, is “just more proof that DAs refuse to truly investigate reported corruption on the part of other elected officials simply because they are corrupt themselves.”

The Tarrant County District Attorney’s Office ignored my requests for details of any local prosecution that resulted from the appointment of an attorney pro tem.

If you think Patrick Wilson’s resignation resolved anything, you are sadly mistaken. The election of Ann Montgomery to replace Patrick was nothing but a continuation of a problem with the DAs office. The illegal email access of a Constables office was also assigned to Ann Macdonald to hound the constable and try to bankrupt him with fake charges resulting in mounting legal fees. Official investigations of officials is nothing but an exercise to placate the public until it blows over.