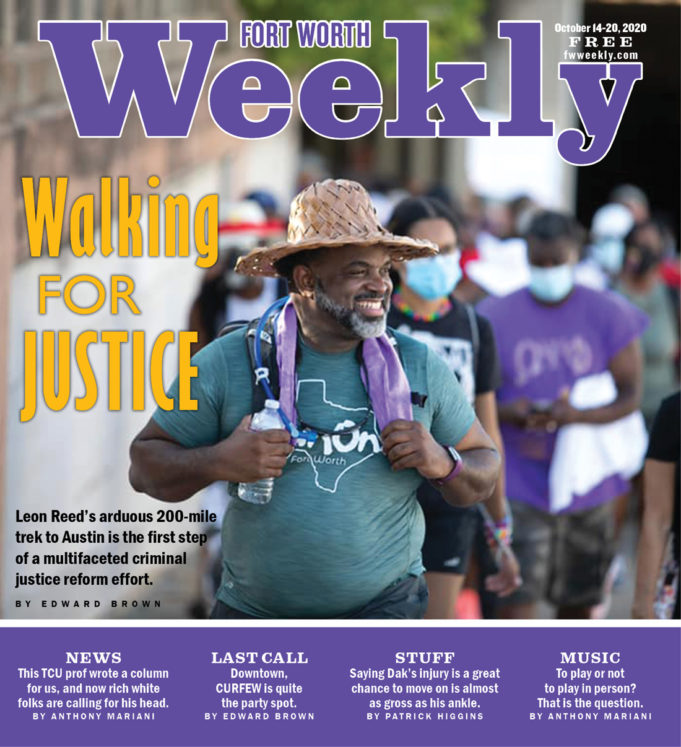

Leon Reed Jr.’s steadfast devotion to social justice issues is fueled by several influences. As a criminal defense lawyer, he sees the results of over-policing in the courtrooms and the protections afforded police on the witness stand. As a retired Marine, he understands that service to one’s country can take many forms. As a devout Christian, he understands that faith works hand in hand with action, and as a Black man, he understands the stakes of inaction for future generations.

To raise awareness of racist Fort Worth policing policies, Reed began a 200-mile trek on August 9 through scorching heat to reach Gov. Greg Abbott. The lawyer did what he could to take advantage of cooler temperatures in the morning, but nine days of walking took a serious toll on his body, he said. Reed undertook the journey not in spite of the physical challenges but because of them, he added. Civil rights reformers of the 1950s and ’60s frequently placed themselves in physically grueling situations as a symbol of their collective resolve to confront injustice at all costs, Reed said.

When Reed arrived in Austin in mid-August, Abbott, somewhat ironically (and perhaps intentionally), was in Fort Worth to chastise Austin City Council for its decision to reallocate police funds as Austinites had demanded. Reed remained in the state capital for 35 days for a meeting with the governor that never happened. Undaunted by the gubernatorial snub, Reed said he holds no malice toward the state leader, although he’s quick to remind Mayor Betsy Price and others that failure to enact meaningful police reforms leaves elected officials complicit in the killings of unarmed Black men and women.

Speaking from a law office on the West Side, Reed described what pushed him to start the Walk for Reform movement that is now a statewide effort to create uniform policing practices across the Lone Star State.

How did your background as a criminal defense attorney inform your desire to affect criminal justice reform?

When you are on that side of the fence, you have access to offense reports, conferences, and body cams. You see a lot more when you are at trial and you catch police officers blatantly lying. It’s like watching someone rob something from the other side of 4 inches of plexiglass. You see it happen, but you can’t stop them.

Minorities have been clamoring for eons for better treatment from Fort Worth police department. When police reform experts put out their report in July [“ Law Enforcement Reform on the Horizon?” Aug. 12], I read the whole 40 pages. It was not a good report. That’s the way African Americans have been treated.

Photo courtesy Walk for Reform.

Do we need less policing or different policing?

As the population grows, we are going to need policing. We can’t have an us-against-them mindset, whether it’s from the police toward the community or from the community toward the police. We don’t walk around with our six-shooter and handle stuff ourselves like we did in the Wild West. We want people to be able to call the police.

I don’t even like the word “defund.” It’s a bad choice of words. If it needs to be explained, it’s poor marketing. Police have to be able to work in communities, and that takes a relationship that is built on trust. Who cares if you have all the funding in the world if police aren’t welcome in the neighborhood.

I expect to be treated a certain way by police. That sacred trust, without it, I am not going to stop for [a corrupt] officer. When the civilians start to clamor, something needs to change.

How did the idea of starting Walk for Reform come about?

I’ve been to Selma. That walk wasn’t a protest. If anything, it was an act of self-sacrifice. I’m going to walk 50 miles along an Alabama stretch of highway with folks out here who could shoot me and not be held accountable. It’s tantamount to a hunger strike. As you watch me waste away, the humanity of the situation comes to light. I thought to myself, “If they can walk 50 miles, then surely I can walk 200.”

The governor had already [mentioned creating] an act to prevent what happened to George Floyd from happening in Texas. OK, you recognize that there is a problem. I want you to know that there are people like me who are committed to this. We have ideas that are worthwhile. We are committed to the effort and to the reform. If Fort Worth won’t do it, maybe we can get it done at the state level.

What goals did you want to achieve by walking to Austin?

Photo courtesy Walk for Reform.

I hoped to shame inactive Fort Worth leaders. Stuff is so bad [in Fort Worth], you have people willing to walk 200 miles to get help. That shouldn’t make you feel good in Fort Worth. We have people who have to walk 200 miles for help because we’re not getting it here.

When you have data, and you show the city their own data, like racial profiling data that has been mandated since 2001, and you see the blip when it comes to African Americans who are overrepresented, you have to ask the city what they did. In 2002, when you saw that data, what did you do? When you saw it again in 2003, what did you do? You can pick any year, and the result is the same. That tells me that you have done nothing. Either you approve, or you don’t care.

The problem is that there isn’t a good tool for self-regulation with police departments. The way things are set up, police have an us-against-them mentality. If you cross a fellow cop by reporting them, you have crossed that thin blue line. Now, they may say that they can’t trust you. If you get a call for backup, they will slowpoke their way to you.

Fort Worth [police] brag about a duty to intervene [when wrongdoing is observed]. Let’s say Officer Smith intervenes when he sees Officer Jones whacking somebody. The following week, Smith intervenes again. What’s missing? What’s missing is the duty to report. I can intervene 365 days a year. If I am bound to report, some of that stigma is off. I have to write a report. It’s the law.

That [and other policies] should be statewide. The duty to intervene and report. Basically, you want to have a mechanism in place where police officers can whistleblow without any risk to them.

Describe specific policy changes that you wanted to bring to the governor’s attention.

Photo courtesy Walk for Reform

There are 254 counties in Texas. If each county has a sheriff, that sheriff will have his or her own policies for use of force. There are 900 municipalities in Texas. If each one of those municipalities has a chief of police, that chief is writing his or her own policies. Now, you have over 1,000 policies. We’re not even counting constables, campus police, and other groups.

If you want to be a Marine, there is one manual and one way of doing things. We have one U.S. Constitution and one Texas Constitution. Why don’t we have one standard, the Texas standard? All of this [can be drafted] in Austin. You don’t want it to be handled only at the local level. There are 111 places that train people to be a cop in Texas. Why do we have to have so many?

The police should not be militarized. In the military, we are trying to kill the enemy quickly and efficiently. The citizens are not the enemy. You cannot instill that type of mindset in the police.

Why haven’t body cameras become mandatory across the state? The public now wants cameras. The police have violence as a tool. We have cameras. If something involved serious bodily injury or death, it could be a felony to not have your camera on. As defense attorneys, we will get 40 clips that are a minute here and two minutes here because they keep cutting their cameras on and off. Why don’t I get one clip of the whole thing?

These things let the public know that there is accountability for police. If you are being held accountable and trained a certain way, then the public will know that they can have confidence in how they will be treated when they are pulled over. Of course, cops should be able to defend themselves. If you are trying to give a ticket and somebody starts shooting at you, of course you have the right to shoot back.

Why do you think the governor snubbed your visit?

I’ve never spoken ill of Gov. Abbott. One of two things happened. Someone from Fort Worth called down to Austin and said, “Hey, don’t see this guy.” I made no secret that I was going to use Fort Worth as an example. I know Fort Worth. Or Austin saw what was happening and asked, “Who is this guy coming down here?”

I believe that, in all likelihood, the reason he didn’t see me had more to do with Fort Worth than Austin because he shortly after came here to try to make Betsy Price look good. That’s when Mayor Price proclaimed that Fort Worth is one of the safest cities in Texas. If you are saying Fort Worth is safe, then you are excluding me and the Black community. That should irritate people.

What plans do you and your supporters have for the future?

Instead of taking a top-down approach, we’ll go bottom-up and get the support of the people. We are building up our website. We are writing for grants so we can fund the research and employ experts in legislation writing.

We are looking to start another group called Together with police chiefs, attorneys, and people who want better legislation written. Conversations lead to questions, and questions lead to answers. We are coming at this humbly. Other states may one day look to Texas. Texas can become the hub for law enforcement policy ideas well into the future. Those policies can become regional and then national policies. If you can’t choke somebody in Florida, you shouldn’t be able to choke someone in Washington.

There was interest in people walking from Houston. Someone said, “How many people does it take to walk 200 miles before the governor acknowledges you?” Maybe it takes more people. We have people ready to walk 90 miles from San Antonio and 120 miles from Houston. We are looking to start up in January. The legislators will be down there.

Every person who comes to Texas should have encounters with the best-trained officers that the state of Texas can give. That officer should understand the parameters under which he or she can do their job. We deserve the best officers that our money, technology, and knowledge can buy. The citizens deserve no less.