Nothing says “Texas” like rodeos, smoked ’cue, and underfunded government services. When public services are cut, Texas always goes big, and the poor suffer the consequences, so why are Gov. Greg Abbott and other elected officials throwing a fit over the mere idea of defunding law enforcement?

From a symbolic standpoint, it’s great to see the Guv putting his foot down to protect a taxpayer-funded service for once, albeit a system that is understood by many to be unsalvageable in its current form given decades of racially driven policing habits and the too-frequent shootings of unarmed Black men and women. Being pulled over for a DWB (driving while Black) is so commonplace that the term has become cliché. Racist policing habits should not be cliché. Racist policing habits should be abolished, and the officers who perpetrate those acts should be ignominiously fired.

In Texas, law enforcement has avoided cuts while other services like mental health, public schools, and health care services are routinely gutted. The Lone Star State enjoys the dual distinction of being dead last in providing mental health services — 51st when the District of Columbia is included, according to Mental Health America — and a leader (seventh) in incarcerating individuals who suffer from mental illness. The relationship between defunding mental health services and jailing the resulting untreated population is well-known. Taxpayers foot that bill while paying into an incarceration system that preys and profits off the unlawyered poor.

Fort Worth police department created the Mental Health Crisis Intervention Team in 2018, but a police review panel recently said that team does not have adequate resources.

“There are cases that police respond to that involve people who are mentally ill and need a critical assessment,” said panel member Alex Del Carmen, a criminologist with decades of experience in training police. “They need someone to take care of them. We feel that in a city the size of Fort Worth, we have a limited number of personnel who are Crisis Intervention Team-trained. If you add to that the fact that they were only available from 9 to 5, those services may not be available when they are needed by the community.”

The availability of a psychologist or other mental health professional allows for interventions that don’t involve handcuffing, tasing, or other potentially harmful police actions, he added.

In the weeks following the release of the police panel’s preliminary results, Fort Worth police department said it began expanding its Mental Health Crisis Intervention Team and training every officer on how to handle interactions with individuals who are experiencing a mental health crisis. Steps are being taken to divert non-police calls to mental health providers, the department said.

After publicly stating this past August that any city that defunds their police department risks losing property tax revenue, Gov. Abbott recently doubled down on his push to protect law enforcement budgets by going after protesters.

“Today, we are announcing more legislative proposals to do even more to protect our law enforcement officers as well as do more to keep our community safe,” Abbott said last month before laying out proposed laws that would create felony-level offenses for individuals who destroy property during an event that is deemed a “riot.”

Giving police the discretion to declare a protest a riot places important Constitutional rights, like freedom of speech, in jeopardy.

*****

Investments in public schools are an investment in the lives and livelihoods of future generations. After cutting and never fully restoring $5.4 billion in public school funds, Texas took steps to shore up underfunded schools by passing House Bill 3 last year. The $11.6 billion bill provides money for Texas classrooms and boosts teacher pay. The Lone Star State ranks about in the middle (26th) on teacher pay. That victory may be short-lived, though.

Texas is slated to receive $1.2 billion that has been allocated to public schools through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) passed by Congress and Donald Trump last March. Rather than add those funds to school districts that have been burdened with unplanned technology purchases and other COVID-19-related expenses, the state plans to proportionately reduce education funding, effectively freeloading off the federal government.

Courtesy of American Psychological Association

Speaking to the Austin American Statesman last June, the head of Texans for Public Education, a public-school advocacy group, said the “state is hijacking that money by reducing the state contribution by an equal amount.”

School officials have good reason to fear further cuts under the guise of budget restraints. The appearance of a “broken” public school system provides ammunition for even more gutting of taxpayer funds for Fort Worth classrooms and boosts to that subtler form of public-school defunding: school vouchers.

Arguments over school funding are inextricably linked to who can afford quality education and who can’t. Last month, dozens of well-to-do parents, largely from the Tanglewood neighborhood, gathered outside the Fort Worth School District Administration Building to demand the immediate resumption of in-class learning. One male protester — and his message was not the exception that morning — held a sign that read, “ ‘Virtual’ Property Taxe$ 2020.” What he effectively meant was “No In-Person Classes, No Taxes from Us,” forgetting that taxes are intended for the greater public good and not for self-serving private (or, in this case, public) services.

Prompting the rally was a Fort Worth school board decision to postpone in-person classes due to public health concerns. The average home value in Tanglewood is around $600,000, according to Zillow. Maybe the sign-holding gentleman thought that paying high property taxes entitled him to a disproportionate say when it comes to Fort Worth school dealings. The sense of entitlement was palpable.

COVID-19 has shown the fragility of Texas’ health care system, especially regarding the uninsured. Among the 50 states, Texas has the highest percentage of residents without health insurance (17.7%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau), partly due to a decision to not accept Medicaid expansion under the Obama administration. By not joining the 39 states that have accepted the federal program that partly relies on state funds, an estimated 1.2 million Texans continue to go without health insurance unnecessarily, according to The Commonwealth Fund, a private foundation dedicated to improving the U.S. health care system.

Rankings compiled by U.S. News & World Report placed Texas 37th overall in terms of health care services, 47th in access to health care, 41st in health care quality, and 20th in public health services. The disparity in who has access to medical care in the Lone Star State may explain some unsettling realities of who is stricken and recovers from COVID-19 in this country.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lists race as a risk factor for contracting COVID-19. The increased dangers for Black, LatinX, and other minorities are due to “socioeconomic status, access to health care, and increased exposure to the virus due to occupation (i.e., frontline, essential, and critical infrastructure workers),” the CDC says on its website.

Black Americans are more than twice as likely to contract COVID-19 and nearly five times more likely to require hospitalization for COVID-19 than white Americans. LatinX adults are nearly three times more likely to contract the deadly disease than their white counterparts.

******

Understanding the disconnect between Abbott’s love of cutting public services and his ardent desire to maintain bloated city police budgets — typically one-third of city budgets — requires an understanding of what law enforcement means to different groups. Just as segregation and Jim Crow gave racist Southerners a replacement for slavery, “law and order” provided a new system of oppression against Black and LatinX men and women following the end of segregation.

Photo by Jason Brimmer

A 26-year-old and recently uncovered interview with Nixon advisor John Ehrlichman describes federal efforts to use law enforcement to target Black men and women at the time.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and Black people,” Ehrlichman said. “You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing those heavily, we could disrupt those communities. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Policing habits and prosecutorial efforts that target minorities and the poor have sown distrust among the victims of police brutality. A recent Gallup poll found that 56% of white adults and 19% of Black adults stated they had either “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the police. The gap marks the largest racial divide found on the poll of more than 16 major U.S. institutions.

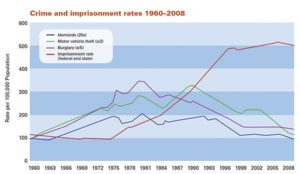

The American Psychological Association said in a 2014 report that “over the past four decades, the nation’s get-tough-on-crime policies have packed prisons and jails to the bursting point, largely with poor, uneducated people of color, about half of whom suffer from mental health problems.”

While Fort Worth public schools are scraping by and local nonprofit mental health groups like NAMI of Tarrant County rely on donations to cover services that the state is not providing, life is good — and profitable — for the local law enforcement industry. Earn the title of police chief in Fort Worth, and the salary easily tops out at nearly $250,000 a year. The highest-paid county official is the district attorney, the apex of a food chain that gobbles thousands of largely poor, largely dark-skinned locals into Tarrant County’s shithole jail every year. If you have any doubt as to the conditions of our tax-funded county jail, the Texas Rangers were recently brought in to investigate the eighth death in that downtown facility this year.

While Fort Worth public schools are scraping by and local nonprofit mental health groups like NAMI of Tarrant County rely on donations to cover services that the state is not providing, life is good — and profitable — for the local law enforcement industry. Earn the title of police chief in Fort Worth, and the salary easily tops out at nearly $250,000 a year. The highest-paid county official is the district attorney, the apex of a food chain that gobbles thousands of largely poor, largely dark-skinned locals into Tarrant County’s shithole jail every year. If you have any doubt as to the conditions of our tax-funded county jail, the Texas Rangers were recently brought in to investigate the eighth death in that downtown facility this year.

Private companies like Recovery Monitoring Solutions and others garner tens of thousands of Tarrant County dollars (plus fees from unconvicted defendants) to create a digital jail and hell for individuals who have to maintain the devices and to keep up with monthly payments for pretrial services.

A 2019 article by ProPublica found that “across the country, defendants who have not been convicted of a crime are put on ‘offender funded’ payment plans for monitors that sometimes cost more than their bail. And, unlike bail, they don’t get the payment back even if they’re found innocent.”

The Weekly recently reviewed county documents related to a local defendant who was arrested three times due to technical problems related to his ankle bracelet and the resulting false alarms. Reforming state-sanctioned human rights violations requires strong leadership from the top. Austin’s Travis County recently elected José Garza to the position of district attorney in a landslide victory and symbolic win for the types of criminal justice reforms that are nonexistent in Tarrant County. When Garza takes office in 2021, his top goals are to treat users of illegal drugs instead of incarcerating them and to bring all police shootings and a greater portion of police misconduct cases before a grand jury.

The debates for and against defunding the police and other areas of law enforcement — which is not the same as disbanding — is not, at its core, about budgets. Behind the dollar signs are two diametrically opposed worldviews on the function of policing and why it exists.

Abbott’s actions and statements as governor have shown that his interests lie with protecting the status quo for the benefit of his donors and the broader business community. Protesters aligned with Black Lives Matter and other reformers see police forces as an extension of a 244-year-old power structure that cares little for the plight of Black men and women and other marginalized groups. Neither group appears ready to budge on their views of how policing habits should change or not.

An increase in Black votes and Black representation in public offices following the civil rights movement was a major indicator of how effective the protesters of that era were in effecting the kind of change that most Americans now agree were needed. Police accountability and moves to end mass incarceration will likely be the measure for the success of today’s generation of reform-minded Americans.

The Weekly welcomes submissions of all political persuasions. Please email Editor Anthony Mariani at anthony@fwweekly.com.