On November 3, while much of the news will be gobbled up by presidential election ads and pundits prophesying the end of the world after this or that candidate is elected, Californians will be voting on a measure that could mark a turning point in the effort to end mass incarceration.

While Jim Crow terrorized Black communities through fire bombings, cross burnings, and outright murder, mass incarceration targets poor Black men and women by working within this country’s legal framework, and its most powerful tool for destroying the lives of America’s poor is monetary bail.

Say you are leaving a live music concert where you partook in a small amount of marijuana — the plant that can be legally used for recreational purposes in 11 states with many more states allowing its medical use. You can rip a bong on the steps of California’s state capital and likely draw little attention yet be thrown in jail in Texas for a minimum of 180 days for possession of even a small amount of Mary Jane. Marijuana laws in Texas are effed up.

If you’re pulled over after leaving the show, your next stop is Tarrant County Jail, our county’s unsanitary and putrid detention center where nine inmates have died this year under the watch of the sheriff’s department. After being stuffed into crowded and possibly COVID-19-contaminated concrete rooms, you’ll eventually find yourself in a small chamber awaiting magistration. There, a Tarrant County magistrate judge who earns $142,000 a year will notify you that you have to pony up $1,000 to leave jail. If you don’t have the resources to pay that bail, you could be looking at several months or much longer in the clink before you reach a plea bargain.

County data gathered through open records requests showed that possession of less than 2 grams of marijuana can lead to bail amounts ranging from $200 to $1,000, based on numbers we obtained from January 1 through January 15 of this year. The average bail set in Tarrant County in 2019 for Class A and B misdemeanors and all felonies, according to the Tarrant County Criminal Court Administrator, was $4,785.09. Bail is posted in full by the defendant (cash bail) or paid through a line of credit issued from a bail bondsman (bail bond). Those bail figures undoubtedly keep many dangerous criminals from committing murder, rape, and other violent crimes, but nonviolent defendants are too frequently caught up in that same system.

As part of recent modest reforms, many first-time offenders in Tarrant County are issued a personal bond, also known as a “personal recognizance” or PR bond. PR bonds require no cash down and rely on your self-interest in having the charges dismissed to ensure you honor your court appointments. Monetary bail requires some level of cash to be handed to the government as a deposit of sorts that supposedly encourages compliance with court proceedings. Receiving a PR bond is never guaranteed, though, especially if you have a prior criminal record. Tarrant County has taken steps to speed up the process of magistration (“ Criminalizing Poverty or Ensuring Justice?” July 8), but that system is still largely based on monetary bail.

The California bill to end monetary bail (SB 10) was passed by the state legislature and signed by the governor in 2018, but lobbyists tied to the bail bond industry successfully forced a veto referendum that ultimately leaves the fate of SB 10 up to voters. If passed on November 3, the legislation will create three risk levels for detainees: low, medium, and high. Low-level defendants will be released from jail to prepare for court while medium-risk defendants may or may not be. High-risk detainees will be considered a danger to society or a flight risk and will be detained until their trial, although they will have an opportunity to plead for pretrial release before then.

One Tarrant county official recently told us that individuals with PR bonds appear in court at a higher rate than individuals who use monetary bail, so why is the county clinging onto that antiquated tool of oppression? The United States is one of a few countries that allow private bond companies to profiteer off the criminal justice system to the extent that it is allowed. A 2017 study by the nonprofit civil rights advocacy group Color of Change and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) found that a handful of companies collectively earn $2 billion in annual profits by bankrolling local bail bond companies, but that alone doesn’t explain why monetary bond is so entrenched in our country’s criminal justice system.

To begin to understand why monetary bail is so hard to abolish requires looking at the machine it feeds and the thousands of locals who earn large salaries operating that machine. Starting at the city level, where arrests are made, around one-third of Fort Worth’s budget is allocated to law enforcement. Fort Worth’s salary schedule for law enforcement is a reminder that public service can pay dividends. Several high-ranking police positions in Fort Worth pay $200,000 and higher. The next level is the county where defendants are jailed and prosecuted. The county criminal justice system is every bit as profitable when it comes to annual salaries. District attorneys rely on convictions (whether through juried trials or plea bargains) to validate the current prosecutorial system. One defendant put it simply.

The convictions, Kevin Jones said, are based on “bail that you cannot make.”

He was describing his current criminal charges for possession of a small amount of methamphetamines — drugs that he maintains belonged to passengers in his car.

“You begin to get weary of the food and the non-visitations,” he said. “Now, here comes the district attorney’s office, and they offer you a plea bargain deal. There are a lot of cards to be considered. If you do not take the offer, you could be facing a two- to 20-year sentence. They offer 18 months of state jail. If you take this to trial, they will push for 20 years. If you take the plea bargain, you get 18 months. You may not be guilty of this charge, but 18 months sounds a lot better. They get their conviction, and you get the lesser sentence. Everybody is happy with that, supposedly. Well, I’m not happy with that. This district attorney threatened me with 20 years for possession of a controlled substance under one gram. That’s unheard of.”

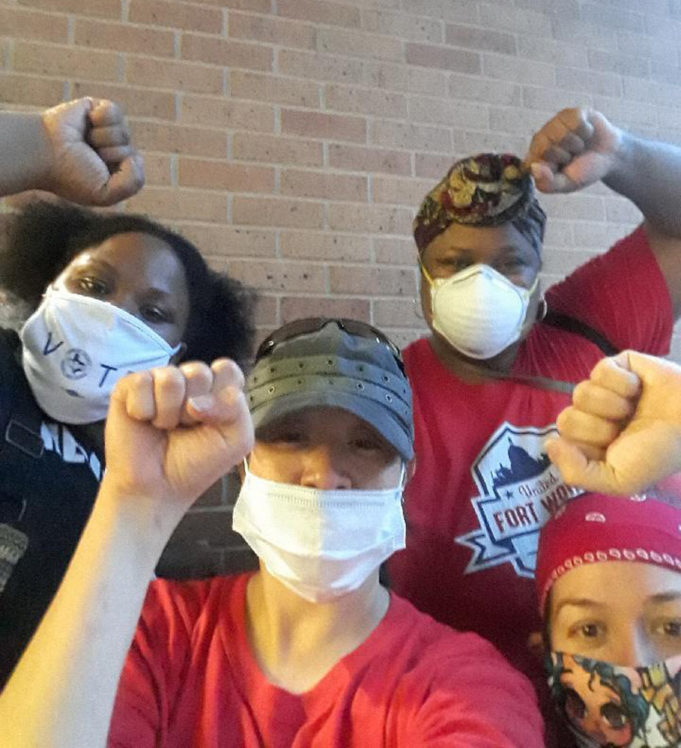

Rather than wait for substantive reforms, members of United Fort Worth’s Criminal Justice Action Team are fundraising for the new Tarrant County Community Bail Fund, which frees Black and LatinX inmates who cannot afford to pay bond for nonviolent, petty crimes that too-frequently result from over-policing in Black and poorer neighborhoods.

When asked if monetary bail pressures inmates into pleading guilty on charges they did not commit or committed under circumstances that a jury would potentially empathize with, a spokesperson for the DA said defendants have the option of complaining on “plea paperwork.” It is up to the defendant and his or her attorney to address improper pressure placed by the district attorney’s office during trial or court proceedings, the DA spokesperson said.

The burden of ensuring that the criminal justice system is fair and balanced should not fall on inmates who may not have the financial resources to defend themselves properly. That burden should fall on the state — the institution that, in Tarrant County, too-frequently targets poor minorities for low-level crimes like trespassing, marijuana possession, and other offenses that result from over-policing. California may become the first state to begin addressing that egregious imbalance if voters approve SB 10. We hope they are not the last state to do so.