Dressed in all black, her hair in long, meticulous braids, Shenita Cleveland stood outside the gates of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) South Central Regional Office in Grand Prairie, holding a large poster over her head with the word “Culprit” written across the top in bold, black letters. The caption was followed by a photo of Juan Baltazar Jr., the regional director of the office. Cleveland, accompanied by about 20 other protesters, had brutal words for Baltazar.

Baltazar, she alleges, should be held responsible for the COVID-19 outbreak racing across area federal prisons, including Federal Medical Center Carswell, a prison that houses female inmates of all security levels who have special medical or mental health needs. More than 500 — or about 40% of Carswell’s 1307 inmates — have tested positive for COVID-19. On August 30, the federal prison system’s website reported that nine Carswell inmates are positive, six have died, and 524 have recovered.

Compared to the rest of the general population, inmates are 5.5 times more likely to catch COVID-19 and about three times more likely to die from the virus, according to a study by researchers at Johns Hopkins and UCLA.

The BOP, meanwhile, claims it is aggressively taking steps to prevent the spread of the virus and is working quickly to place qualified inmates on home confinement.

“Mr. Baltazar is the overseer of operations for … 21 BOPs, including Carswell FMC and Seagoville [Federal Correctional Institute], which includes managing employees that are allowed to violate inmates’ rights to fair and regular treatment during their incarceration among other things,” Cleveland later told me. “Texas is home to the three worst federal prison COVID outbreaks, and all three fall under [Baltazar’s] custody and care and he should be held responsible for misdeeds in the region.”

Cleveland’s appearance at the regional office earlier this month was the latest in a series of protests she has led. For weeks, she has yelled through a large bullhorn toward the brick walls and razor wire of FMC Carswell, hoping someone will listen more so than hear.

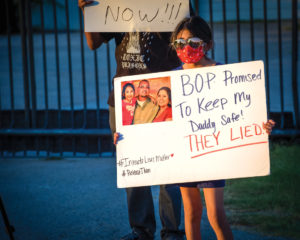

Dozens of impassioned family members, friends, and former inmates follow her, also yelling their grievances into microphones and bullhorns as prison guards and police officers in the background closely watch the protesters. At issue is the activists’ hopes to have some of the inmates released on home confinement or compassionate release, a program that ends incarceration under extreme circumstances, such as a terminal illness or advanced age, for example. Many of the inmates whom Cleveland and her fellow protesters support are nonviolent offenders, she said.

No one is claiming the inmates are innocent, just that they deserve the chance to survive COVID-19.

Carswell’s six COVID-related deaths include former inmate Sandra Kincaid, 69, who tested positive for COVID-19 on July 6 and died on July 15. She was evaluated at Carswell “for shortness of breath, fatigue, and weakness,” went to a local hospital for further treatment, and was placed on a ventilator before she died, according to the BOP.

Another inmate, Veronica Martinez Carrera-Perez, 44, tested positive for COVID-19 on July 9 and died August 3. She was diagnosed at Carswell with low oxygen saturation and taken to a local hospital for further treatment and evaluation. Both women had preexisting conditions, according to the prison system.

“We are deeply concerned for the health and welfare of those inmates who are entrusted to our care, and it is our highest priority to continue to do everything we can to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in our facilities,” the BOP wrote in an email.

The BOP has also started a task force for managing pandemics, the email states.

*****

The virus is an added obstacle on the inmates’ road to redemption, a journey already fraught with struggles between two conflicting sides of their lives. One side is the federal prison system, and the other is love, each a powerful force with a will of its own.

Activists allege that the inmates — the family members and friends they love — have been on lockdown for weeks in cramped prison cells, eating sub-par food, living without adequate protective gear against the virus, and also being unable to get outdoors for some fresh air.

“They’re giving them bologna sandwiches for lunch,” a demonstrator yelled at the Grand Prairie protest.

Someone in the crowed added “purple bologna sandwiches,” a reference to the color of the spoiled meat.

“A bologna sandwich?” the first woman yelled. “I don’t even feed these kids out here bologna sandwiches, and we’re broke as fuck.”

Federal prisons receive ample funding, and bologna “costs a dollar,” she added.

Behind alleged conditions are the disturbing numbers. The figures take on an added severity at Carswell, given the poor health of the inmates housed there.

During one of the protests, family members and friends marched outside Carswell and carried signs that read, “Inmates Lives Matter,” “We Want Justice,” “They Are Not the Threat, the Virus Is,” and “Free Yolanda McDow.”

McDow is one of the inmates Cleveland is trying to have released from Carswell. Cleveland has already helped to secure the release of four inmates from area federal prisons, she said. Their names are Cynthia Brown, Adan Borrego, Lisa Crowe, and Gerald Shultz.

McDow, 54, uses a wheelchair and has asthma and high blood pressure, conditions that place her at risk for serious complications if she catches the virus. She was already approved for release to a halfway house in November, but the pandemic has created a greater sense of urgency, family members told me. Since she is unable to work, McDow’s supporters are pushing for her to be released to home confinement instead.

In addition to protesting, Cleveland writes letters to prison officials and has received at least one phone call from Carswell’s warden, Michael Carr, who promised her that McDow’s release is being “worked on,” she said. Family members said they were hopeful when they were given a July 24 deadline for McDow’s possible release, but the day came and went.

McDow already has signed paperwork stating she can be on home release through 2021, Cleveland said.

“I am here to reason with you again,” Cleveland wrote in a recent email to Carr. “Ms. Yolanda McDow #37471-177 has suffered enough. I believe that you are the answer to Yolanda’s release as previously approved and stated. The evidence against Ms. McDow is suspect at best. She is not a danger to herself or society. Please allow her family to mend the brokenness this has caused and give Yolanda the proper health care she needs to heal.”

Cleveland continued, “It is my hope that you have compassion. I look forward to giving you that credit.”

*****

The protests at Carswell are intended to put pressure on the prison system, but activists allege it has led to retaliation.

During one of the protests, police set up an observation tower near the grass where the group typically stands, and “it was manned,” Cleveland said. A man driving a dark SUV pointed a zoom-lens camera out of the window and snapped their pictures, as shown in photos provided by Cleveland. Several rifle-toting prison guards drove up to the protesters in golfcart-style vehicles.

“It was intimidation,” said Cleveland, who became involved in advocating for the inmates after she heard about what was happening at FMC Fort Worth (a federal men’s prison) and Carswell.

Cleveland and McDow’s other supporters allege that some staff members at Carswell have taunted McDow and told her she’s not going anywhere. At one point, she was threatened with being tossed in the “SHU,” a segregated housing unit and a place of punishment in federal prisons where privileges such as phone calls and letter-writing are often limited.

These things happen when inmates “complain to the outside world,” Cleveland alleged. But she continues to boost the volume on her message. Cleveland has bought three bullhorns, each one progressing in size and power. Her latest model can be heard from up to one mile away and has a blaring emergency-style siren, she said.

The protesters’ voices are loud, but responses remain scarce. Carswell is on lockdown, and days sometimes pass before McDow’s family hears from her. A banner across the top of Carswell’s website reads, “All visiting at this facility has been suspended until further notice.” The restriction is in place due to the pandemic, and family members are worried.

McDow’s father, a widower, told me he wants his daughter home, where they can look out for each other. She previously received Social Security disability checks and is not able to work.

“I need her, that’s for sure,” Yolanda’s father, Sam McDow, told me in a phone interview. “I’m 75 years old and live alone. I just pray every day. I’m very afraid of her catching the virus. I miss her very much.”

Another family member, DeAngela Merida, is McDow’s cousin and one of her best friends.

“We’ve been really close since high school,” said Merida. “That’s when we started to hang out just about every other week or so. Then in my 20s, we always hung out together. We would go out dancing and having a good time, doing all the things girls do.”

McDow’s home became a popular gathering spot after Sunday church services, and family members would watch football, chat, or listen to music, Merida said. She described McDow as “quiet and soft-spoken. She was never the type of girl to be in jail or to be around people who were.”

How did McDow end up in the federal prison system? How does anyone, really? In McDow’s case, it was a tragedy that caused a devastating life change, followed by a series of poor choices.

McDow’s troubles began after tragedy struck in the late 1990s. Following a car accident, her right leg had to be amputated above the knee. As time went on, she became increasingly withdrawn and depressed, Merida said.

“Sometimes you could talk to her, and other times you couldn’t,” Merida said.

The loss of her leg shattered McDow’s confidence, and she began questioning whether she would ever find love again, Merida said.

McDow was missing her whole leg, and in her mind, she felt that the type of men she would normally date — ones who had something going for themselves — would not want her, Merida explained.

That seemed to change when a new suitor appeared in 2008, but when Tony R. Hewitt started coming around, Merida instantly sensed that something was wrong, she said. “He just didn’t seem like the type of man she would normally date.”

Hewitt is the son of a pastor and a preacher himself, but he ended up being the devil in disguise for McDow, Merida explained. He eventually became one of the leaders of the so-called Scarecrow Bandits, a group of six robbers who hit area banks in 2008. Hewitt was sentenced to 355 years in federal prison for the crimes, and others involved in the robberies also received heavy sentences.

During their brief courtship, Hewitt drew McDow in and convinced her to serve as a lookout person for the bank robberies, Merida said. McDow waited in a getaway car blocks away but did not go inside the banks or participate in the violence leveraged by the criminal gang. The group’s collective list of criminal activities included discharging a taser on a bank employee, leading police on a high-speed chase, taking an innocent person hostage, holding guns inches away from bank employees’ faces, and carrying assault rifles during the robberies. In all, the bandits committed 21 robberies in the Dallas area from June 2008 to January 2009, according to court records.

McDow cooperated with the FBI and other law enforcement, and her attorney promised to negotiate a plea deal with a five-year prison term, Merida said. Instead, the deal fell through, and McDow was sentenced to nearly 16 years in prison in 2008. That was 12 years ago.

When asked about McDow’s possible release to home confinement, Carswell administrators referred my questions to the BOP office in Washington, D.C. The first response I received was an email signed “Office of Public Affairs” with no name: “While for privacy reasons we cannot provide you with information pertaining to the conditions of confinement or release plans for any particular inmate, we can provide you with the following information. Given the surge in positive cases at select sites and in response to the attorney general’s directives, the BOP began immediately reviewing all inmates who have COVID-19 risk factors, as described by the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to determine which inmates are suitable for home confinement.”

The BOP, which has 127,242 federal inmates in the facilities it manages, reports on its website that it has placed 7,559 inmates on home confinement.

“The BOP was originally focused on a priority list of inmates in accordance with the attorney general’s guidance to BOP issued March 26, 2020,” the email continues. “However, the attorney general’s memo issued on April 3, 2020, asked the BOP to immediately maximize appropriate transfers to home confinement of all appropriate inmates held at Oakdale, Danbury, Elkton, and other similarly situated facilities. That process is ongoing.”

The email goes on to state that the Department of Justice gave the BOP the authority — under the attorney general’s memos — to determine “which home confinement cases are appropriate for review in order to fight the spread of the pandemic. The BOP has been proceeding expeditiously consistent with that confirmation.”

The prison system also insists that case management staffers are “urgently reviewing all inmates to determine which ones meet the criteria.” Further, additional resources are in place to “make appropriate determinations as soon as possible.”

All inmates are being reviewed, but an inmate who believes he or she may be eligible for home confinement can provide a release plan to their case manager. Additionally, the BOP may contact family members to gather needed information when making decisions concerning home confinement placement.

One former Carswell inmate who was released amid the pandemic is Lea Ann Blystone, a former San Antonio businesswoman who in 2015 was sentenced to seven years in federal prison for her part in a $1.4 million wire fraud scheme. Her sentence was part of a plea deal she made with the government, according to published reports.

During her time at Carswell, Blystone said, the basics were in short supply. She alleges that inmates must “beg for toilet paper” or are told to buy it on commissary. Ditto for hand sanitizer and cleaning supplies, even after the pandemic hit. Social distancing among inmates is virtually impossible, she said.

“The inmates are living in tight quarters, and the guards also were often not wearing a mask or gloves,” she alleged. “It was an absolute nightmare. We ran short of supplies and never had good cleaning supplies.”

Blystone also alleges that the prison system took away McDow’s prosthetic leg for more than a year under the guise of repairing it, and “when she got it back, it still didn’t fit,” she said. Despite that and having difficulty navigating the prison grounds due to her wheelchair, McDow “was a champ” and never complained, according to Blystone.

“Overall, prison is not a fun place to be in the first place,” Blystone said. “Carswell is called a hospital of horrors. You cannot get any of the medical or dental care you need. I have lupus, and when I went in, I was told, ‘You’re going to get the best medical care.’ Not true.”

Blystone alleges that she has also experienced retaliation for speaking out.

On one occasion, a priest at Carswell was interrupted in the middle of a Christmas service and berated for not answering his radio, Blystone alleges. An administrator yelled at him so loudly that he made the priest cry, she said.

Blystone complained in a letter to the warden and shortly after was sent to the SHU, the segregated housing unit. She also alleges that the guard followed her around and told her she didn’t want to “go down this road with him.”

Blystone said her main point is that “it’s hard to speak up for your rights or you will get retaliated against.”

Other retaliation crosses into the criminal, Blystone alleges. “As far as physical, sexual things going on — it happens. Inmates get preyed on a lot.”

Her experiences have left her with a desire to help the other inmates. “I’m trying to advocate for the people I left behind.”

*****

McDow is not alone. There are other reports of inmates being promised they would be released, only to have the process dragged out. One of them is Kimberli Himmel. Another Carswell inmate, the 61-year-old has Stage 2 breast cancer and kidney failure, the Washington Post reported in April.

Himmel told the Post there are about 65 women in her unit and about half of them are 55 or older. Most of them suffer from kidney failure or cancer — or both, the report stated.

Long before the pandemic hit, we reported in 2019 on Barbara Gasich, a Carswell white collar criminal who was terminally ill with cancer. Samy Khalil, a partner with the Houston law firm Gerger Khalil & Hennessey and a former assistant federal public defender, was called in to remove Gasich from Carswell on compassionate release. Khalil is regarded as one of the top white-collar criminal defense attorneys in the nation. He was able to get Gasich out but not without a lot of wrangling.

Before arriving at Carswell, Gasich had a documented medical diagnosis that she was terminally ill. Her family said at the time that they believe her stay in Carswell increased her suffering and shortened her life.

The Fort Worth Weekly has documented many other stories of maltreatment at Carswell as well.

Merida and Cleveland are hoping something similar does not happen to McDow. So is her father. Although McDow was recently given a release date of late November, that’s another three months of having her exposed to the virus, they said. They’re left wondering why McDow has to wait it out inside Carswell with so much at stake.

“It’s not too late for them to do the right thing,” Merida said.