The United States accounts for 4.4% of the world’s population but nearly a quarter of COVID-19-related deaths. The fact that the wealthiest country continues to experience the worst global rates of coronavirus cases and deaths has been a source of embarrassment for Donald Trump.

Never one to accept responsibility, the president sought to blame the World Health Organization (WHO), claiming the international agency did not provide ample enough warning about the virus. In fact, the WHO warned Trump and other world leaders of the crisis beginning in January. Now the United States joins Brazil, India, and the Russian Federation as COVID-19 hotspots.

The Trump administration’s finger-pointing has been rebuked by a growing body of research and reporting by foundations and prominent publications that have researched the underlying economic factors that determine who in America is more likely to survive a COVID-19 infection and which groups are being hit hardest by the ongoing pandemic. That research is forcing public and private discussions on economic inequality, the strongest factor that determines how long Americans live, how likely they are to financially thrive, and even how fulfilled they feel with life.

Black Americans continue to die from the novel coronavirus at a rate of three times that of white people, according to recent data by APM Research Lab, a team that focuses on challenges facing the nation. The comprehensive study gathered statistics from 40 states and 92,128 recorded COVID-19 deaths. Last May, Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, Alex Azar, stated that the lopsided death toll was partly the fault of Black communities and partly the fault of hospital policies.

“Unfortunately, the American population is a very diverse population with significant comorbidities that do make many individuals in our communities, in particular African-American and minority communities, particularly at risk here because of significant underlying disease comorbidities,” he said, referring to obesity and diabetes, among other chronic diseases. “That is an unfortunate legacy of our health care system.”

The New York Times recently noted that the high occurrences of COVID-19-related deaths among Blacks can be explained by “decades of research [that] shows that Black patients receive inferior medical care to white patients.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has acknowledged the role that economic inequalities and other societal disparities play in determining which socioeconomic groups are most likely to survive an infection by the novel coronavirus.

Social conditions, the CDC found, can “isolate people from the resources they need to prepare for and respond to outbreaks.” The federal agency has provided policies for countering “implicit bias” and “cultural barriers” that hinder care. Those steps include learning about “social and economic conditions that may put some patients at higher risk for getting sick with COVID-19.”

The Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a research and grantmaking organization, has noted that “too many people lack the basic protections that would have slowed the spread of the virus.”

Photo by Edward Brown.

Lack of paid sick leave, cramped living conditions, limited access to health care, and an inability to shelter in place due to the lack of savings are all factors that adversely affect the poor, the center said. In the United States, poverty is unevenly distributed by race with Blacks (27.4%) and Hispanics (26.6%) experiencing poverty at significantly higher rates than whites (9.9%), according to the Economic Policy Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

Speaking for Fort Worth’s Stop Six neighborhood on the East Side, Quinton Phillips, who serves as a Fort Worth school district trustee, said his community has banded together to ensure that the elderly and vulnerable in the community are safe and fed during the pandemic.

“I look at our community as indestructible in many ways because we already had to deal with poverty,” he said last April. “We can last, but that doesn’t mean that we need to be neglected in the meantime.”

*****

Life for America’s wealthy elite bears little resemblance to the subsistence living of working-class Americans. Among the bottom 90% of household incomes, the vast majority of earnings come from labor while the top 1% unevenly benefits from generational wealth, dividend earnings from stocks, and other passive forms of income, according to Economic Policy Institute.

In Fort Worth, those disparities have defined daily life for wealthy and poor locals during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the shelter-in-place orders that were strictly enforced last March and April, remote work was not an option for many in Fort Worth’s predominantly Hispanic North Side (“ Shelter Times,” April 15). Local business owner and longtime Northside resident Esmeralda Morales said at the time that many in her community immediately lost work due to the shuttering of restaurants and other small businesses. Food pantries were the only service preventing starvation for many Northside residents, she said.

Local community leader Arnoldo Hurtado, describing the crisis, said, “If we stay inside, we starve because there is no food, due to lack of money. We’ve learned that it has to be we the people who stop relying on the big, messy political and institutional departments who are only looking out for themselves and their interests.”

The “telework disparity,” which refers to the uneven abilities of individuals to work from home depending on their race and socioeconomic status, was evident to Morales and Hurtado. Reporting by Vice found that just 16.2% of Hispanic workers are able to work from home, compared to 30% of whites and 37% of Asian Americans. Essential work, such as maintaining power lines, working construction sites, and delivering food, falls heavily on Hispanic men and women in North Texas.

Dallas-based UT Southwestern Medical Center recently said in a public statement that Hispanics at the medical center test positive for COVID-19 at a rate of five to seven times that of any other ethnic group. Compounding that problem is a lack of testing in poor communities. In a May 27 article, NPR found that COVID-19 testing sites in Texas are more commonly located in whiter neighborhoods.

*****

Among G7 nations (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and United States), the United States has the greatest economic disparities. Americans are aware of the economic imbalances that have defined daily life in this country for more than a century. The Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan think tank, noted in a 2020 study that 61% of adults polled said there is “too much economic inequality” in the United States, and a majority of respondents said addressing that problem would require significant changes to the country’s economy.

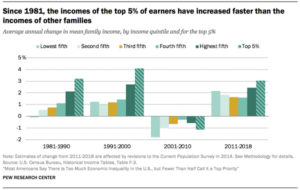

Research from the institute found that the average wages of working Americans have not kept pace with overall productivity. Top one-percenters saw their salaries grow at five times the rate of the bottom 90% of wage earners between 1979 and 2015.

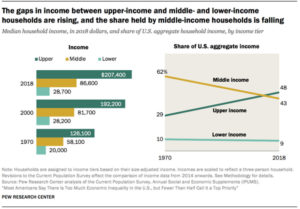

In 2018, the top 20% of earners garnered 52% of the U.S. income, according to the Pew center. That divide is growing, the think tank found. In 1968, the top 5% of earners accounted for 16% of overall U.S. income. In 2018, that group accounted for 23% of annual earnings. The disparities are even starker when it comes to overall wealth.

According to the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, the wealthiest 1% of U.S. families hold 40% of the country’s wealth while the bottom 90% of families account for less than a quarter of U.S. wealth. The median income gap between white and Black Americans continues to grow, from $23,800 in 1970 to $33,000 in 2018, according to the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Pew center has found a strong partisan component to the data. Nearly 80% of left-leaning respondents were concerned about economic inequality while only 41% of conservatives polled were worried about the divide. Fewer than half of adults in the study believed that addressing economic inequality should be a top priority for the country.

Photo by Edward Brown.

Weeks of Fort Worth protests following the death of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white police officer as three officers watched have made economic and criminal justice reform top priorities for reform-minded locals. Via Twitter (@enoughisenoughFW), the grassroots group Enough Is Enough has posted images of city budgets and demands that police funds be partly reallocated to provide social and mental health services. Mayor Betsy Price and city staff have begun meeting regularly with protesters to find ways to address grievances. Many protest leaders remain skeptical that meaningful police reform is on the horizon.

Protesters lost a significant and highly symbolic battle when Fort Worth residents voted to renew Fort Worth’s Crime Control and Prevention District (CCPD) last July. The half-cent city tax adds $85,733,428 to Fort Worth police department coffers each year. In the weeks before the vote, supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement canvased homes and ran online campaigns to draw attention to the CCPD’s allocation of funds for “enhanced enforcements” that include SWAT and Special Response Team officers.

Fort Worth police chief Ed Kraus recently stated his intention to divvy up the CCPD funds in a manner that provides greater resources to mental health support and fewer funds for SWAT and other militarized policing teams.

The protesters are aware that money, and who controls it, is at the core of the struggle for racial equality. Dr. Martin Luther King survived turbulent civil rights marches only to be killed after turning his focus to economic inequality.

“It is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages,” he said during a March 1968 rally in Memphis — three weeks before his assassination.

*****

Nearly half of U.S. states will increase their minimum wage (from the federally mandated $7.25) this year, according to Paycore, a human resources and payroll software company. Texas’ minimum wage remains tied to the federal minimum wage, which hasn’t changed since 2009. The annual income of someone working full time on minimum wage is $15,080. Individuals like waiters and bartenders who rely on tips can be paid as little as $2.13 an hour. To earn a living wage — the minimum needed to meet basic needs like food and rent — a single adult with one child would need to make at least $24.64 an hour.

The term “slave wages” has historic roots. Following the abolition of slavery, Blacks in the South were left with few job options and took jobs (as waiters, porters, and other service-based workers) based on the promise of tips.

Seven states currently ban bar/restaurant owners from using tips to make up for low wages, meaning those establishments are required to pay the state minimum wage.

In 2017, 3% of Texas workers earned minimum wage, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Last year, Dallas County raised the minimum hourly wage of county employees to $15. In Fort Worth, efforts to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour have been led by Fair Wage Fort Worth. The volunteer group has worked to sway public officials at the city, the Fort Worth school district, and Tarrant County to raise wages for government employees and staffers.

Speaking before the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee in 2019, economist Elise Gould testified on rising inequality in the United States.

“I am an economist with particular expertise on wages and wage inequality,” she said. “Income inequality is the primary reason why the vast majority of Americans experienced disappointing growth in their living standards over the last four decades. In other words, most Americans are seeing slow income growth because most of overall income growth is going to households at the top.”

She advised that policymakers take steps to raise the federal minimum wage, expand eligibility for overtime pay, address gender and racial pay disparities, and protect workers’ rights to bargain collectively for higher wages and benefits.

Through a public statement posted on BlackLiveMatter.com, director Kailee Scales said that during a global pandemic, the impact of racial bias is clearer than ever.

“This virus is devastating to us,” she said. “We are the essential workers who keep the country going. We cannot just #stayhome. We have never had access to adequate health care in our communities, and many of us don’t even know we have the preexisting conditions the coronavirus feeds on. Our children historically suffer in our education system and are now at risk of falling further behind due to a lack of access to virtual education programs. We will continue to shine a spotlight on the inequalities that continue to upend our communities. We will continue to demand our communities receive the resources and support we need. We will continue to fight for our lives.”

Silly Communist.