It was nerve-wracking when Monna first took the stage. Her hands were shaking, and her heart was pounding. She could barely look up from her phone, where she’d typed up some jokes to deliver to the room. She didn’t know what to expect, but she was determined to give standup a try.

Icons like Jim Carrey, Dan Cummins, and Rob McElhenney had shaped her sense of humor and love of standup. Monna knew she wanted to become a comedian, but open-mic nights in her hometown of Fort Wayne, Indiana, were more about beat poetry than humor. It was January 2013, during a trip with friends to Indianapolis, that she took a chance.

Stopping by the comedy club, she started chatting to one of the local comics and mentioned she wanted to do standup. He asked her to tell him some jokes, and after that, she landed her first gig –– a six-minute set at the Indy club’s upcoming showcase.

Looking back on the experience, Monna, now sitting in a coffee shop on West 7th Street, smiles as she remembers that first set. On that memorable night, she introduced one of the first jokes she’d ever written.

“One of the jokes was, ‘Men love women with curves. That’s why I’ve always been jealous of girls with scoliosis. You can laugh. I don’t have it –– I’m ahead of the curve,’ ” she said.

The joke went over well and even got her out of a traffic ticket that night, she said.

Monna has since become a fixture of the Fort Worth comedy scene, hosting four weekly open-mics and performing regularly at Twilite Lounge and MASS. As a full-time comedian, Monna is a familiar face to Fort Worth comedy fans and is a supportive figure for other women in standup, a genre of comedy that isn’t known for its accessibility to women. Even in Fort Worth, a city with a diverse comedy atmosphere, standup is still male-dominated and uniquely challenging for women.

It isn’t Monna’s gender that makes her so popular, of course. She’s popular because she’s funny as hell, from witty observations (“How do you get evicted from an igloo? Does someone come by with a hairdryer and liquidate your assets?”) to relatable commentary (“I realized I had a flat tire as I started my period. I’ve never felt so deflated and bloated at the same time.”).

Monna has headlined at the Arlington Improv, Addison Improv, and Dallas Comedy House. On Saturday, March 21, Monna will help produce the inaugural Fort Worth Comedy Festival, which will feature shows and workshops on the Near Southside. The FWCF website describes the event as spanning multiple comedy genres and focusing on local acts, including kids’ shows. (Performance schedules will include age ratings.)

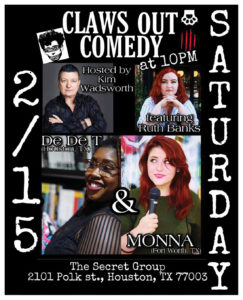

Her next big step is taking her all-female lineup comedy show, Claws Out, to perform at The Secret Group in Houston -–– and then San Antonio.

“I’m super-excited for all the upcoming shows,” she said. “I’m happy to have found a medium that showcases female performers as well as promotes local businesses.”

Monna’s stage presence has changed dramatically since that first show seven years ago. She’s more relaxed, and her delivery is more confident. She looks unfazed and comfortable under blinding stage lighting, strolling up to the mic and chatting with the audience like she’s been doing it forever.

Still, the stakes are high at each performance. As a booker once told her, when it comes to winning over an audience, “Men have 30 seconds. Women have 10.”

•••••

Monna’s auburn hair seemed to glow under the blue and purple lights while she introduced each act at MASS’ “Laugh your MASS off” open-mic recently. Contrasting that fire was Monna’s delivery: dry, mellow, and free-flowing, like she was talking to each audience member one-on-one. She said she prefers to keep her sets conversational rather than a series of one-liners. That way, she can make her performances less performative and more authentic –– a voice she’s adapted to and molded over the last seven years.

Fellow comic De De T described Monna’s style as deadpan and witty with a dark edge. The darkness likely stems from the heavy subject matter Monna usually addresses in her sets. Drawing material from her personal life, she often talks about strained family relationships and her experience with mental illness.

“It took me, I think, four or five years to start talking about being bipolar onstage, because I would start to talk about it, and then people would get weird, and then I would get weird … so I would just stop and move onto something else,” she said.

That changed when Monna finally decided to finish the joke. Someone came up to her after a show and started talking about their own experience with mental illness.

“That made it that much easier to keep developing it and talking about it, because you never know who’s listening and who’s feeling less alone,” she said.

If the audience isn’t feeling the heavy stuff that night, she said she can always go to a more straightforward topic: drinking.

“It’s just an easy attention-grabber based on where you’re at,” she said. “If you’re in a bar, it’s easy to talk about drinking. I can’t just start with the mental illness stuff a lot of the time –– you have to make people trust you first.”

That trust, she believes, is harder to earn for female standups than males. Monna said she wasn’t surprised when she first heard the booker’s comment about women having 10 seconds to prove themselves onstage. She had been doing comedy for several years by that point and had already felt the judgment for herself.

Judgment is inherent to standup, Monna said, as audiences often view a new comic as someone who hasn’t earned their spotlight. When taking the stage, one has to prove themselves worthy of a laugh. When it comes to women in standup, Monna said she thinks expectations are higher because being funny is assumed to be a male trait.

“I think that women aren’t encouraged to be funny,” she said. “I think from childhood, men are encouraged to be funny. … The class clown is always the boy shooting milk out of his eye.”

The adage that women aren’t funny sounds out-of-place in modern parlance. Carol Burnett, Lucille Ball, and Betty White have long been household names, and Netflix has featured numerous female standup comics on the streaming platform’s comedy specials.

But bookers frequently don’t like to hire more than one female comic per show, Monna said, because they expect their material will be repetitive. With this added constraint, Monna believes talented comics often go unnoticed.

Fort Worth comic Hannah Vaughan echoed this point about biased booking and said she’s heard bookers say that, while booking an all-male lineup isn’t a problem, all-female lineups would turn away audiences.

“People are like, ‘It’s not about gender. It’s about being funny.’ I’m like, ‘OK. Well, then bookers need to start acting like it,’ ” Vaughan said.

When looking for open-mics or performance venues, Vaughan said knowing the host of a show is female gives her reassurance that she won’t be criticized for doing comedy.

“I want to see myself onstage,” Vaughan said, “and if I see another woman onstage, that’s one step in the right direction, and [Monna] does that.”

During De De T’s five years performing in North Texas, the comedian who now lives in Louisiana said Monna and other “comedy broads” in North Texas always listened to one another, keeping one another accountable but also lending support during hard times.

Monna has certainly become an advocate for women in local comedy, lending support by creating Claws Out. The monthly all-women show, which will take place at assorted venues, is intended to help new female comics establish themselves in the industry while still being paid to perform. Admission to Claws Out is free.

“A lot of the time, women, they start, and they’re so funny, and then they don’t get encouraged, so they quit,” Monna said. “I’m trying to provide an opportunity that’s a paid experience for people to validate them and also validate them within the scene.”

She added that paying the performers is an important part of the program because comedians are often expected to do comedy for free. The least she can do, she said, is help a comic pay for gas.

“Even if it will always be out-of-pocket, I always pay people, because I don’t want to be asked to do something without compensation” she said. “I think it’s insulting.”

Vaughan, who has performed at Claws Out, said the show offers a valuable opportunity for comedians to feel supported and nurtured –– something she said isn’t common in many venues.

“Something I’ve noticed is you’ll go onstage, and you’ll perform your set, and the person who’s hosting –– typically a male –– will say something about your body or will say something about whether he does or doesn’t want to fuck you,” she said. “That happens all the time. And if you’re watching that happen, and you look over, and you see the person who booked you on the show laughing at that joke –– how do I feel supported in that environment?”

In the face of such commentary, Vaughan said women are told to “just deal with it,” that this is how things work.

“I think a lot of the people in power are kind of the old guard,” Vaughan said, “so when new people come in, they see that this is a pattern, and they start to follow suit. … These younger generations of comedians have learned that this is acceptable behavior.”

In contrast, Monna is helping create an environment where women can speak up if they feel uncomfortable, Vaughan said. In a workplace, she added that support is vital to a woman’s growth.

Sexist comments from male comedians are a challenge that De De T said she considers childish.

“I find male immaturity to be the greatest occupational hazard to female-identifying comedians, but that’s mostly more bark than bite,” she said.

To encourage cultural changes among venue owners, De De T added that performers should favor working at venues that are owned and run by women.

“I say just go where you feel appreciated and don’t bother wasting a thought on anybody who doesn’t see your value,” she said.

•••••

Monna works independently in a field that requires constant exposure and vulnerability. While being one’s own boss might sound liberating, Monna said working alone has its challenges. Not only does she run a business, book gigs, produce a monthly comedy show, and navigate a competitive industry in general, she does it all without the support of an HR department or corporate structure to fall back on.

As a result, she and other female comedians have to create their own supportive network for giving advice –– such as what venues to avoid, who not to trust, and which bookers will expect something in return for booking them.

“The only support system in comedy really is each other,” Monna said. “For instance, if there’s somebody in San Antonio who’s drugging people’s drinks at shows, the only thing that we have to do is word of mouth. Maybe every once in a while, a list gets circulated that’s like, ‘Hey, if you work with this guy, watch out.’ That’s the best that we have.”

That is why her advice for female comics is the same advice she’d give any woman at a bar: order a new drink every time you leave one unattended and be careful who you’re talking to.

On top of her regular MC spots and running Claws Out, Monna recently started teaching a workshop that includes self-defense. The need for self-defense doesn’t just stem from concern about walking through dark parking lots at shady venues, Monna said. Typically, it’s audience members, bookers, or showrunners who make women feel unsafe during and after shows.

Vaughan is no stranger to the fear. Once, after a show in January 2018, she dashed to her car holding her keys like brass knuckles in case one particularly aggressive audience member followed her.

Meanwhile, De De T said she’s heard comments about women not feeling safe at venues but that safety is always a concern for women.

“My take is that the world isn’t all that safe for women, period,” she said. “As such, I haven’t noticed a marked difference in comedy than from any other spaces I’ve been in.”

Vaughan said she’d like to see male showrunners and venue owners take female acts seriously and listen when they voice safety concerns. Another change Monna would like to see is female comics no longer being called “comediennes,” a feminization that she and many other comics consider condescending.

What makes live comedy unique, Monna said, is the experience of looking the comic in the eye while he or she is onstage. The relationship between audience and comic is special because it allows everyone to feel like part of the moment together, she said. For that reason, she believes seeing a show live is always better than streaming standup specials online.

“Being present and in the moment is a much more special experience, and you never know what may happen in a live atmosphere,” she said.

She said crazy things happen at live shows all the time, adding to the fun. Once she had an audience member learn what “getting the light” meant (that the comic’s stage time was over) and who tried to light comics early to get them offstage.

“I once gave a comic the light at my open-mic, and the comic said, ‘Oh, I have a minute left?,’ and a woman in the audience yelled at him, ‘You have 30 seconds!’ ” she said.