Fort Worth is an extremely wealthy city. We are home to several billionaires, a PGA golf course, several world-class museums, and an internationally renowned symphony that plays in acoustically spectacular Bass Performance Hall. We are home to the quadrennial Van Cliburn piano competition. We have gas wells, oil wells, well-respected research universities, and four- and five-star hotels. We have a Central Market, where swordfish is flown in daily and sold at nearly $24 a pound, and where beef tenderloin goes for $35 a pound, and that store is packed every hour it is open. We have thousands of McMansions selling for $200,000-$400,000 each. We are rich.

And yet nearly one out of every four children here is in a situation where they are food insecure. About 15 percent of our residents live in poverty, which is about 130,000 people, and that number is rising despite the current low unemployment numbers, according to several major charitable nonprofits I spoke with for this story. How is that possible in a city so wealthy?

There is a multitude of answers. Some people have brought poverty on themselves through drug and alcohol addictions. Some simply don’t have the mental capabilities to manage their lives, and some suffer from PTSD or other illnesses that prevent them from maintaining a job or pursuing a career. There is generational poverty, and there is the difficulty of securing work if you’ve done jail time.

There are also a lot of people who run into difficult times because of medical issues or a missed paycheck or three. They are the working poor, people who work one or two jobs who just cannot manage to pay their bills on time or handle financial emergencies regardless of their efforts. And when it goes awry, it can happen very quickly. One day you’re up. Two months later, you can find yourself homeless.

I know because I’ve been there. I know how it happens and what it’s like to have to ask for help. I know how difficult it is to admit you simply are not making it when you appear to have all the tools and have, in fact, been working and working hard all your life. I have been mostly working poor since arriving in Joshua, just 20 minutes south of Fort Worth, from New York City 18 years ago.

•••••

“Asking for help is hard,” said Kimberly Nix Lawrence from Catholic Charities of Fort Worth, one of the oldest charitable nonprofits in the region. “It is humbling and often humiliating. For those most in need in our society, our traditional model of providing financial assistance or case management is often transactional, cold, and ineffective. Rather than motivating people to keep going, this process often makes people feel helpless and hopeless. Instead of moving forward, people get stuck.

“Most assistance programs solve an immediate need,” she continued. “Your electricity is going to be cut off? We’ll pay the bill for you. Problem solved. Except that the disconnection notice was a symptom, not the problem. The problem is that the family can’t afford electricity. The assistance the family received did not resolve the problem. Many might ask, ‘Why don’t they solve the problem themselves by getting a better job?’ ”

For people on the edge, Lawrence said, landing a better job isn’t always an option. “Imagine you’re exhausted from working two minimum wage jobs that don’t even pay your bills,” she said. “Your car broke down, so you’re sitting in the cold waiting for the bus that was supposed to come 10 minutes ago. Questions race through your mind: ‘Am I going to be fired for being late? Is the daycare going to kick out my kids because I don’t get my paycheck until after the bill is due? How am I going to get that electric bill paid?’ Are you feeling overwhelmed yet?”

For a lot of Fort Worth’s neediest, East Lancaster Avenue is base camp. It is home to a couple homeless nonprofits, including Union Gospel Mission and the women’s shelter. On any given morning, the streets begin filling up with people who stayed the night but often have very little to do during the day. They wander the streets around the missions and other charities in the area waiting for strangers to pull up and start serving food from the trunks of their cars.

My friend M. brings brisket and mac ’n’ cheese a few times a year and serves them until he runs out. He was out just a week or so ago.

“You know,” he said, “I hadn’t been there in a few months, but I swear it’s getting more crowded all the time.”

M. is not being identified because he was homeless some time ago and does not want people to know that when he sold used cars he slept in his own car on the lot before cleaning up in the office bathroom. He was one of the lucky ones who managed to pull himself up before he sunk down further.

Keith Ackerman, Union Gospel COO, agrees with my friend that more people, especially more Fort Worthians, need help these days.

“We’re a homeless outreach organization, so most of the people we see are homeless or unsheltered,” Ackerman said. “They need a place to stay, food to eat, today, right now, but the way the economy has fluctuated, well, a lot of people who historically would have referred to themselves as lower middle class are finding themselves in more difficult financial situations and so have to supplement what they have with food banks and emergency financial handouts. Certainly, services geared to the working poor are being accessed by more people. There are a lot of folks who have to humble themselves to look for relief.”

•••••

The Tarrant Area Food Bank is a nonprofit that collects and distributes food to Fort Worth and 13 surrounding counties. Bennett Cepac, associate executive director, said that despite low unemployment, a large number of the jobs “pay minimum wage but not a living wage –– a lot of our clients work two jobs to make ends meet.”

The food bank primarily provides food but also has an outreach program to help people sign up for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, Children’s Health Insurance Program, Medicaid, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and “any other programs they might be eligible for,” Cepac said. “We help them go through the paperwork process.”

It is hard to imagine that the food bank provides 40 million pounds of free food in the area annually, enough for about 30 million meals a year. That comes to 600,000 per week. Most of that food, Cepac said, is donated, with about one-third coming from government resources.

I asked him where the heck did he manage to accrue 40 million pounds of food annually?

The donated food, he said, comes from stores like Kroger, Walmart, HEB, Target, and another 165 or so grocers in the area.

“All of the big retailers have distribution centers in the area,” Cepac said. “And when things get to the loading dock that are not considered first grade, they are refused, and we pick it up.”

The food bank has a fleet of 12 tractor-trailers that bring the food to the food bank center for sorting.

“We get produce that’s slightly off color or two or three days out of date,” Cepac said. “We get day-old bakery items like breads and pastries, cans that are dented, manager’s special meats.”

He said that I should never buy manager’s special meats because if they’re not sold, they will go to the food bank. “And we need them.”

Asked if the number of people needing a hand was increasing, Cepac said it was: “In Johnson County alone, we distributed 650,000 pounds of food in the last quarter of this year. That’s a 45-percent increase over the same quarter last year.”

The food bank partners with about 300 local charitable nonprofits — all of which have to meet USDA food handling requirements and must feed everyone. “None of our partners can discriminate against anyone,” Cepac said.

That means, he said, that there are a lot of places where he would love to help but can’t because they won’t serve people without proper identification or who are transgender, for example.

Taking care of the hungry is the food bank’s primary task, but Cepac said the organization realizes that effort needs to be made to lift people up on their feet as well, so that they no longer need immediate help. To that end, the food bank has a culinary arts program that lasts 16 weeks and graduates about 35-40 students per year.

“Nearly everyone who passes the course can get a good job placement that pays a living wage,” he said. “We follow up with them for a year afterward, and we’ve got an 80-percent retainment rate for those people.”

•••••

Another place that strives to lift people out of poverty is the Fort Worth Hope Center on Loop 820 South. They provide food and clothing at specific times during the week — they served more than 100,000 meals to neighborhood people last year — but they also have a forklift school.

“People need help,” said JoAnn Reyes, Hope Center president and a cofounder. “Sometimes they have to choose between paying rent or buying food. Sometimes it’s a choice of food or gas for your car to get you to work. Then there are the grandparents on fixed incomes who are taking care of their grandkids because their own kids are in jail or otherwise not doing it. We’re always going to look out for those people.”

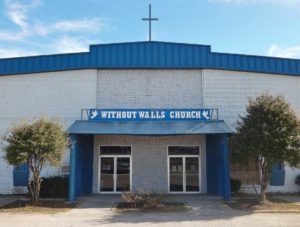

The church that she and her husband run, the Without Walls Church, also operates the School of Hope, which trains people to become certified as forklift operators.

“With all of the industry that’s come into Fort Worth and nearby areas, there is a huge need for forklift operators,” Reyes said, “and those are good paying jobs. They’ll pay at least $15 an hour and sometimes $20.”

It’s a one-week course that typically takes 30 hours to complete. When people pass, they receive their certification. Cheryl called the course a lifesaver. She took it a couple of years ago and was back for recertification on a particular type of forklift last week.

Cheryl, whose last name is being withheld to protect her privacy, is typical of the working class who become working poor, who then have the floor drop out from under them. She was a middle-class housewife from Texas who married and moved to Florida. For 25 years, she leased a booth in a hair salon and worked as a hairdresser. Three years ago, she and her husband divorced. It was not amicable.

“By the time we were getting divorced, he’d already moved our retirement money somewhere that I didn’t know about, some secret place, so I had no money, nothing,” she said. “I walked away from everyone and everything I had known, all my friends, my work, my home.”

Cheryl moved back to Texas with a small RV and parked it on her sister’s lot — her mother lives with her sister — and started to look for work.

“So I was starting over at 57 with a resume that said ‘self-employed’ for 25 years,” she said. “Good luck with that. I wound up at different food banks just to manage.”

Cheryl heard about the forklift classes, thought that certification might open some doors, and jumped.

“The class was great,” she said. “I finished, got certified on four different machines, and got a job.”

She has to travel an hour each way to and from work, but she is thrilled to be back on her feet: “I have my mom, my sister, and a job. Things are working out the way they should, I think. The first two years of trying to start over were really tough. I had to ask for a lot of help moving back from Florida, but this last year, well, things are leveling off, and I’m pretty happy with how I’ve managed things.”

Hope Center partners with the Texas Workforce Commission, which pays for the forklift training. “And then,” Reyes said, “we have extra training, in how to write a resume, how to apply for a job, that sort of thing. And we’ve got an in-house staffing agency, so we know where the jobs are to send our men and women out to apply.”

Reyes said the school also trains ex-offenders, because the warehouses doing the hiring don’t discriminate against them. And the truth is that a lot of ex-offenders make exceptional workers. They don’t want to go back to prison.

Most of the classes have about five students, though the school can accommodate up to 10 at a time, Reyes said. The school has been in operation for seven years, and as many as 300 people have graduated.

“Ideally, we provide a resource that allows a person to become independent and self-sustaining,” she said. “That’s what we’re after.”

•••••

Catholic Charities, which was started nearly 110 years ago, partners with the food bank, whose Cepac spoke glowingly of the organization and its new CEO, Michael Grace.

“There are a lot of causes of poverty and why it’s growing,” said Grace, who’s been in his position since May 2019, “but our focus isn’t really on why there is poverty. It’s what are we doing about it. That’s the question. What we’ve done at our office, and all Catholic Charities are run differently, is to make a concerted effort around three key strategies to achieve getting people out of poverty: create, eradicate, and transform. We’ve designed our entire agency around those three concepts. We create solutions to eradicate poverty and transform the conversation around aggressive poverty.”

I asked him how that translates into practical solutions.

“When someone comes to us and needs help paying bills, what we do is ask them why they are in that situation? Did they lose a job? Is it generational? What is the cause of that need? Now if they are just looking for a handout, we’re not that charity. There are crisis charities for people who need food and clothing right now, people who need a place to sleep tonight.”

Grace’s work falls into a longer-range camp of moving people out of poverty altogether: “We’re not the right agency for you if you need a quick fix.”

Grace’s idea of removing someone from poverty includes four goals: They need to get off government assistance, find a job that pays a living wage of at least $15 an hour, have no harmful debt — he describes a mortgage as a good debt while a payday loan is a harmful debt — and possess the ability and willingness to save money at least six months of every year.

“We generally work with the working poor, people who can work a job,” he said. “Now a lot of people cannot do that, but a lot of people, if they lost their job, they’d lose their house or apartment in a couple of months. That’s where we come in. We will even offer them financial assistance, but we will do it strategically while they are working with us.”

One of the people who’s recently been helped is Marcia, who is 47 and whose last name is being withheld to protect her privacy. “I had never dealt with unemployment,” she said. “I worked so regularly that I did not realize I was living paycheck to paycheck.”

The mother of one girl, Marcia divorced in 2013 and began receiving $230 monthly in child support. It wasn’t much, but it didn’t matter because Marcia was earning a healthy $64,000 a year as a clinical researcher and registered EKG technician. “I always worked,” she said.

Her last job was in pulmonary research, and she held it for five years before burning out: “I found another job, but it didn’t work out. They weren’t happy with me, and I was not happy with them.”

Marcia applied for and was granted unemployment benefits in August 2018. She thought she would find another job quickly, but nothing materialized.

“I went on interviews but didn’t get call-backs,” she said. “I’d never experienced that in my life. I went through the entire six months of unemployment without finding work. It was shocking to me.”

By January 2019, she was running out of unemployment benefits and growing desperate. Despite having made good money, she had no savings and went to Good Shepherd Church asking for help with her utility bill. She said they helped with the bill but began communicating with her about a longer-term solution — in particular, about developing a strategy for putting some money in savings when she found another job. The church, in turn, put her in touch with Catholic Charities, which she first visited in March 2019.

“They didn’t just help me with a caseworker who taught me how to save,” Marcia said. “They helped with the mental and emotional aspects of reintegrating into the workforce as well. They also helped with the rent while I continued to look for a job.”

She found one a month later, a clinical research trial involving blood transfusions, but continued to work with the charity caseworkers.

“They visit weekly and encourage me to develop a good savings plan,” Marcia said. “And it is working. This is the first time I’ve ever had savings.”

She was also encouraged to develop other areas where she might be able to earn a living if her research dries up again. To that end, she’s working on a medical billing certification.

Grace said, “We have an intensive process that will involve our case managers and everyone else to be involved in all aspects of your life. People might need transportation to a job. It might mean childcare that is keeping someone from holding a job. We don’t provide that but will put people in touch with organizations that do. If you need education, we have a program working with community college students and work with at-risk students to get their degrees.

“In other words,” he continued, “for us, the question is ‘Are we working at getting people out of poverty or just providing a band-aid?’ We work at the former.”

Catholic Charities’ 2019 numbers are pretty impressive. The charitable nonprofit provided 80,000 rides to people needing to get to work or medical centers, met the medical needs of 330 people, and helped 700 students via Catholic Charities’ school program.

“You know,” Grace added, “it doesn’t matter how wealthy the city is or how low the unemployment rate is when 35 percent of all the jobs here are low wage or minimum wage.”

•••••

“It is very sad,” said Deborah Bullock, operations manager for the Salvation Army in Fort Worth, “but in the last few years, we’ve seen an increase of people needing help here. We’re averaging 600 calls monthly for people needing rental help, and we provide rental assistance to probably 25 to 40 families each month.”

The organization receives funding from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and other sources for those who reach out who are eligible. For those who are not, the Salvation Army provides referrals to keep people from becoming homeless — a situation Bullock said is terribly difficult for a person or a family to extricate themselves from once things become bad.

Janine Smith, a Salvation Army caseworker, said, “The reality is that housing has become very expensive here. If people miss one check, that will often put them behind. One unexpected emergency will cause them to call us because they will be behind on their rent. A lot of things can go wrong that put people behind, like auto repairs, lack of transportation to and from work, medical incidents, people who get caught in payday loans. We are seeing a rise in working poor because of all of those reasons.”

Despite all of those enormous efforts, as well as the efforts of hundreds of other charitable nonprofits and other outreach programs, the poverty-stricken, the homeless, the hungry, and the working poor continue to appear. Their numbers should be going down but are not. In this city of enormous wealth, in this era of historic low unemployment, how is that possible?

There are an untold number of reasons, probably one for each person who needs help. The working poor who need a hand all have stories to tell, yet they are reserved about telling them. The working poor maintain their pride and don’t want to be seen as parasites dependent on the largesse of strangers.

I came to Texas from New York for family reasons. I thought I had a plan. I had been the editor-in-chief of a national magazine and a chef in New York City with good reviews. I’d quit cooking when I was able to make a living as a writer and had stories and opinion pieces published in The New York Times, the New York Daily News, Playboy, Omni, Elle, and many other major magazines around the world. When I left New York, it was with an assignment to keep working on my magazine’s website, and I thought I had a done deal for a small syndicated weekly column for the alternative press. I was imagining maybe $1,500 a week between those two gigs.

Once I landed in Texas, I bought a modest home for $85,000 and had put about 20 percent of that down. With the few bucks I had left from New York after moving, I bought an old Ford Ranger, a push mower for my near two acres, and house furnishings. I put my kids in school, made them lunches daily, and thought I was doing it all the right way.

But then everything fell through. The syndicated column that I’d been led to believe was a done deal never materialized, and the work on the web for my old magazine disappeared about eight weeks after I arrived in Texas when a new publisher was hired who didn’t know me. I was out of money and ready to lose the house I’d just bought three months earlier. I wasn’t a quitter, so I applied for jobs. I applied at the then-new Walmart distribution center in Godley, at Alcon, at Mrs Baird’s bread factory, the Miller-Coors plant, and dozens of other places. I applied at restaurants all over Fort Worth. Nothing came of it. Nobody needed a chef who hadn’t worked in the kitchen in 15 years, and no plant or factory wanted an unemployed 50-year-old investigative journalist hanging around to maybe write a story about their operations.

I finally sucked it up and went to work at the Fort Worth Day Labor Center — which has since closed — and did all of three days’ work in the 35 days I spent there. Again, nobody needed a 50-year-old guy to dig ditches or put up fencing when there were lots of 30-year-olds hanging around. Little did my three kids know that some of the groceries I brought home during that time were coming from a local church that was kind enough to share. And until they read this, they still don’t know that.

Unlike a lot of people in that situation, however, I had friends in New York and elsewhere and a large family that had faith in me. Despite them all dealing with growing families, I was able to borrow mortgage money to make it through some months when there was zero income. It was painful and humiliating, but I did it. And while I had no real connections in Fort Worth, I had written a couple of freelance stories for the Fort Worth Weekly and was able to turn my disastrous five weeks at the Day Labor Center into a cover story to pay a month’s mortgage. And then slowly, I began to land some freelance work and more work at the Weekly — including reviewing restaurants, which allowed me to bring home a free meal for the family nearly every week. The state took some land of mine for the Chisholm Trail Parkway and gave me a few bucks that tided me over. I wrote a book that brought in several hundred dollars a month. An elderly aunt died and unexpectedly included my brothers and sisters and me in her will for $3,000 each. Things turned around. The kids never got quite what they wanted for Christmas, but they stopped worrying that a stocking with a Slinky, playing cards, beef jerky, and a pair of 40-buck sneakers was all they were going to get.

Still, there were times in our first few years here when the electricity and water were shut off for a week or two. I blew credit cards out of the water until no one would give me one. My older kids still laugh when they think about how much we relied on big bags of chicken thighs and rice. “Dad,” they still say now and then, “I never knew there were 200 ways to cook chicken thighs.”

I was lucky. I kept the house and managed to keep my family’s head above water while the kids grew up after that very rough patch. The two oldest are on their own now and doing all right. My youngest is finishing college in a few months. She’ll be fine, too.

But not everybody has that large family — nearly all of whom have been paid back in the last decade — from whom they can borrow, so they reach out to charitable nonprofits, which, for some, is the hardest hit their pride has ever taken.

To say people bring poverty upon themselves because of alcohol or drug addiction is a gross misunderstanding of addiction.

I think that the idea of them bringing it on themselves is that they made that initial choice to try it. No one ever tries dugs or alcohol thinking I am going to be an addict, but they do know that it can happen. Fortunately, I have never been tempted, but I have loved some family and friends who were tempted and tried and ruined lives were the result. I think from the angle the author was writing, it was not a condemnation. It was a quick pass because the focus of the story was not how we as a society can combat and help those people, but rather how some are helping others. Just a thought.

I agree with Lucy.

Addiction is a disease.

I totaled my car in March last year which resulted in me losing my job that I held for eight years. I’ve been looking for a job ever since. People who haven’t gone hungry don’t have a clue what it’s like to have to go to food banks and the judgment you have to put up with from some people who think you’re just not trying. Now Trump’s going to take away my $17 I get per month in food stamps which doesn’t sound like a lot but it is to me. I search for a job every day all day and I can’t get anywhere. My biggest fear is being homeless.

Very informative and eye-opening. As a retired teacher, still young enough to work, I was very interested in the programs to help people get education. Teaching is a calling, not a profession for me. I will begin researching that avenue.

I hope that the commenters actually took the time to read this whole Peter Gorman piece which i found to be one of the best I’ve seen here in several weeks. What I got out of it was pure inspiration that in spite of adverse conditions: relocating to a strange place, career changes, age discrimination, money in very short supply, the author never gave up, raised three great kids, kept the family together, and triumphed. My favorite columnists here are Prince Lin and now Gorman. I just wish he would use his real name for restaurant reviews because anybody who can “fix chicken thighs and rice 200 different ways” likely knows what he’s writing about!

Great piece! Thank you for writing this, Peter! I don’t think most people realize how prevalent these issues are and they just assume that it could never happen to them. A college professor once told me that 80% of Americans are a month or two away from homelessness given the right circumstances and it really resonated. I thought “he can not be right.” However, after living through some interesting turns of my own…like most recently health problems…and talking with people around me, I know he was right. All it takes is a few unexpected turns to knock the wind out of the average American’s financial sails and most of us have no idea where to go for help so it is easy to get overwhelmed.