One late afternoon this fall, I sat on a park bench under a mammoth oak tree visiting with a few of the residents still remaining at Butler Place, Fort Worth’s oldest public housing apartments, at 1201 Luella St., east of downtown. Drake, James, and another gentleman who would not share his name commented on the view from what some call “The Hill,” the highest point in the complex. Most Fort Worthians do not realize how lovely the vista is from this elevation, despite being landlocked by concrete, noise, and traffic. Glancing one direction, you can see East Fort Worth with its abundance of trees, and in the other, there’s downtown. At the time of my visit, the sun was beginning to set behind the shimmering, skyscraping Omni Hotel.

These residents enjoy their frequent afternoon get-togethers especially when the weather is nice, but they are aware that soon, these visits will cease. Butler Place is closing. More than half the doors and windows are already boarded, casting a ghostly feel over the entire area. The move-out began late 2017 when the first families were relocated to various apartments across the city. This process will continue until late 2020, when all residents are relocated, resulting in “deconcentrating” low-income housing.

“I know what’s gonna happen,” said the gentleman with no name. “It’s gonna be part of downtown. Some big shot investors have come in, and they wanna connect it to downtown. Be like 7th Street. Life is a cycle. That’s how God made it. To most folks, Butler’s just an eyesore. To others, it’s home.”

Built on what was then called Chamber Hill, Butler Place was part of the federal public works programs during the Great Depression.

“Butler was a mixed blessing from the beginning,” said Richard Selcer in his 2015 book, A History of Fort Worth in Black & White. “It did clear out a major slum, but clearing the site also uprooted an entire neighborhood, displacing long-time residents who had sub-standard housing but also a sense of community.”

Today, Fort Worth Housing Solutions (FWHS), an organization that reports directly to Housing and Urban Development (HUD) but works closely with the city, occupies what was originally the first black school in Fort Worth, the Colored High School, built in 1909. According to John Roberts, Fort Worth historian and preservationist, the school was renamed in 1921 for Isaiah Milligan Terrell, the principal. It later became Carver-Hamilton Elementary School after the larger I.M. Terrell High School was built nearby.

FWHS is overseeing the closing of Butler Place as well as Cavile Place, Fort Worth’s other low-income property, at 1401 Etta St. in the Stop Six area (called Stop Six because it was the sixth stop on the interurban streetcar that ran in the early years of the last century). FWHS is participating in a new initiative called RAD (Rental Assistance Demonstration) that is seeking both public and private funding for new and renovated housing for low-income people, thus keeping rental costs low.

Butler residents are able to choose from among about 12 properties, according to Margaret Ritsch, FWHS director of public affairs. Residents are assigned a number, and when a new property becomes available and their number is drawn, they are able to make the move.

Plans are still in the works for the Butler Place structures. Public meetings were held in late September with representatives from FWHS, Historic Fort Worth, Tarrant County Black Historical and Genealogical Society, I.M. Terrell Alumni Association, community advocates, residents, and a number of other organizations. One proposal is to establish a museum on the grounds, with historic preservation a key goal.

•••••

Late afternoon is the best time to catch residents out and about and ask about their upcoming relocations. Although they have input on where they will move, opinions and emotions vary. After my visit on The Hill, I strolled to the north end of Butler to a much lower elevation of the 42-acre property, where I encountered a woman named Audrey.

“I’ve lived at Butler five years,” Audrey said. “I grew up in Fort Worth, went to [Polytechnic] High [School], and then moved to Colorado. I became homeless. I got three kids, the youngest, 19, is still with me. My rent here is only $50 per month. I know it’ll go up when we move. I like it better here on the north end. It’s more families. Up The Hill has more violence, more drugs. I just keep to myself. I don’t mess with people here. I try to get the management to recycle. Everybody throws all their plastic and paper in the dumpster. It fills up fast. I don’t like telling people I live here. They look at you differently when they find out.”

Shay and Bud live near the center of the complex. They moved to Butler several years ago from the east side of Fort Worth. The couple hopes they can remain through the winter months.

“This place wasn’t so bad until crack hit in the late ’80s, early ’90s,” Bud said. “The [Drug Enforcement Administration] was here the other night. Drugs are rampant.”

He pointed to a bullet hole in his front window. “Happened not too long ago,” he said. “Luckily, no one was standing on the inside when it hit.”

“It took me five years to grow my flowers, and now they are all gone,” she said as she pointed to the side of her unit.

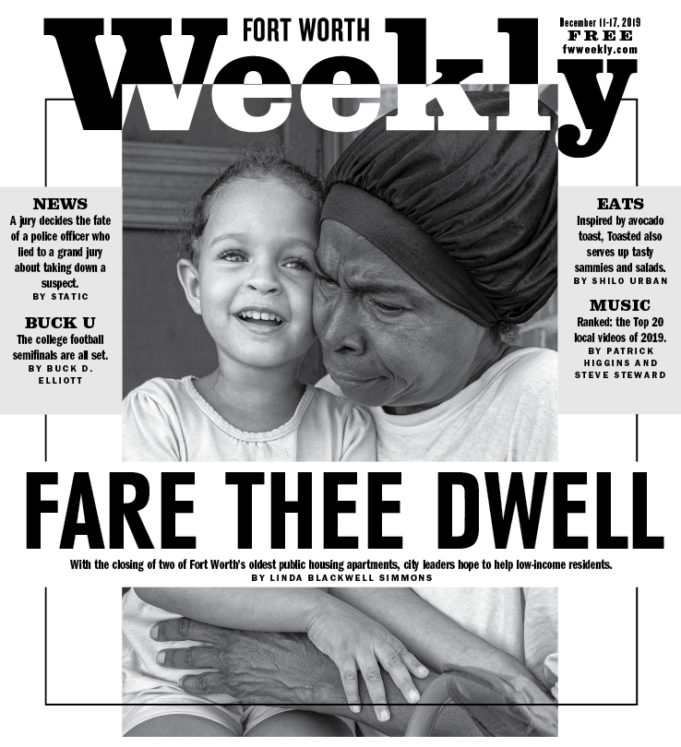

As I was walking back to my car, I spotted an older woman sitting on her step with a little girl of about 3. Delbra was her name and Sophie, her granddaughter. Delbra moved to Texas from Virginia, where she spent 16 years teaching school.

“Things have calmed down since folks started moving out,” Delbra said. “The ones who are left mostly stay to themselves. There are lots of problems. The apartments are mold-infested, and there are rats, and my bushes were torn down. Now the front is bare. When the maintenance person came and I wasn’t here, my door was left unlocked.”

•••••

Cavile Place, at 1401 Etta St., is Fort Worth’s other low-income housing apartment complex. Built in the 1950s, Cavile has 300 units. Residents will also be relocated, but unlike Butler, the Cavile relocation is not operating under the RAD system. Instead, FWHS received permission from HUD to demolish the site and provide tenant protection vouchers to all residents, granting them an opportunity to move to neighborhoods with better access to jobs, schools, and other amenities.

A community meeting was held at Cavile in mid-October, attended by FWHS, city officials, and a number of community advocates. A $35-million HUD Choice Neighborhood Implementation grant was submitted to HUD in early November. Fort Worth is in competition with approximately two-dozen other cities to receive these funds. It will take about six months for HUD to make its decision.

McCormack Baron Salazar, a real estate development firm specializing in renewal and sustainability of low-income housing, has been engaged to lead the implementation team in the urban redesign of Cavile and the rest of the Stop Six community, returning vacant land to productive use. This firm said it will work with FWHS, the city, residents, and the community at large to transform the area. The focus, the firm said, is on three primary components –– housing, community, and people. Renderings presented at the meeting highlighted 1,000 new living units with mixed income, decentralizing poverty while spreading investments throughout the neighborhood. A multipurpose hub is planned for Cavile’s center that will encourage community engagement, including recreation, a health clinic, a library, restaurants, retail, community gardens, sports fields, improved street lighting, curbs and guttering, and additional police visibility. The goal is also to work with Trinity Metro to augment mass transit. If the grant is approved, 2026 is the target date for completion of the renewal.

The redevelopment will replace the 300 apartments currently onsite. To date, 182 vouchers have been issued. Housing will offer a mix of unit sizes and structure types and will include choices for families as well as seniors and opportunities for both rental and ownership. When the new units become available, current Cavile residents will have first choice to return, if they desire. The housing plan addresses the needs of today’s approximately 250 Cavile households, along with about 50 families on the FWHS Section 8 waiting list. Large and small businesses will be encouraged to invest, thus bringing more money into the area.

“Yeah, we’ll see,” said a woman sitting next to me at the meeting who would not share her name. “They’ve only been talking about this since 2012, and so far, nothing’s been done.”

“Cavile’s been my home for seven years,” said Brenda, the woman who sat on my opposite side. “I’m from East Texas, and before I moved here in 2012, I was told by a lady in management that it was pleasant and safe. Then the day after I moved in, my apartment was broken into and my television was stolen. Then the same thing happened in 2014 and again in 2016. The police came, and they tried to help, but I never got any of it back. I’ve seen fights right here on the property between the Crips and the Bloods. I’ve been told I’ll get my voucher soon. I’m glad. I’m ready to move.”

“There was a darkness when I first came to Stop Six,” Milton said. “It’s hard to explain. I never lived in Cavile. I’m educated, I work, and I support myself, but I do have a stake in Stop Six. You have to take care of what you have no matter how little. People here can’t blame the folks on [nearby] Camp Bowie [Boulevard] for all their problems.”

FWHS President Mary Margaret Lemons said she is proud of Milton and her garden. FWHS, Lemons said, was able to give her more earth to expand her farm through a land lease. “We anticipate working with Ms. Milton to foster a healthy neighborhood, which is one of the objectives of the” Stop Six transformation, Lemons said.

Tom Deloye, chief RAD officer for El Paso, said his city, which is comparable to Fort Worth, began participating in the RAD program several years ago and is now 90 percent through the process.

“El Paso’s experience, based upon 43 RAD property conversions totaling over 4,500 housing units to date, is overwhelmingly positive for the residents,” Deloye said. “Through new construction and substantive gut-rehabilitation of the apartments, infrastructure, and grounds, the residents enjoy the quality energy-efficient and attractive apartment homes. We are enthusiastic about the significant opportunity RAD has provided to both the residents and El Paso’s housing authority to bring vibrancy and stability to neighborhoods. And we were able to do this without burden to the local taxpayers.”

Doloye said El Paso assigns a staff member as a caseworker to each resident.

“We hold their hands, train our movers, and have very few resident complaints,” Doloye said. “We prioritize residents’ interests as best possible.”

•••••

Opinions vary from residents who have already relocated.

One is Rocio, who spoke over the phone. Not long ago, she moved to The Standard at Boswell at 8861 Old Decatur Rd. northeast of Saginaw.

“I like Butler better,” she said. “Do you know if we can move back when the renovation is done?”

She would not share with me why she wanted to return to Butler.

Monique grew up in the country and moved to Butler nine years ago. Raising three children there, one still with her, she recently relocated to the west side of Fort Worth, to the new Palladium Apartments near Hwy. 820 and I-30.

“I love it out here,” she said. “I even have woods. I grew up in the country, and I’m a country girl. Butler was OK. I never experienced crime or any trouble, but I’m glad we’re gone. And the move went so smoothly. My new apartment is nice and quiet.”

Another resident who recently left Butler is Margaret Jennings, 93. For 61 years, she lived at Butler, where she raised her two sons, Devoyd and Jerry, on her own.

“My mother said she would never leave Butler after living there so long,” said Devoyd, or Dee, who is president and CEO of Fort Worth Black Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce. “They would have to tear down the bricks first. After a meeting or two, I went back and told her, ‘Well, Mama, they are tearing down the bricks, so you are going to have to move.’ ”

Devoyd said that back in the 1960s, when he and his brother grew up at Butler, it served its purpose and was a good faith community during those days.

“I think housing has changed for the better,” he said. “It will be good for the people who live there now to be spread over the community at large rather than concentrated. They will get a chance to see other people and see how other people live and maybe learn something from them. Maybe they will get a better understanding and do better than what they are doing, maybe be around some folks who can show them how to do things better. My mother likes her new place. It has trees, and it’s quieter. I think what FWHS is doing with the Butler move is much more efficient than what happened with the Ripley Arnold teardown in 2003. That was a ruckus.”

Ripley Arnold opened in the early 1940s as one of Fort Worth’s first public housing properties. It was located downtown on the property now occupied by Tarrant County College.

Melanie Campbell, senior vice president with CVR Associates, a national consulting firm specializing in affordable housing solutions, is working with FWHS and a number of other cities across the country. She has been in this business for two decades.

“The best aspect of these various public housing redevelopment efforts is the outcome for the residents,” she said. “These families will no longer live in outdated, obsolete apartments that don’t receive sufficient federal funds to maintain in good condition. Instead, they will live in updated or new apartments in high-opportunity areas. The greatest challenge in this work is always funding. The nation’s public housing has an estimated capital needs backlog of over $30 billion, so the limited funds available to reinvest in these properties are very competitive.”

Gyna Blivens said she has been excited about the Cavile plan since first hearing about it.

“I believe better days are ahead for the residents leaving Cavile,” said the city councilmember, whose District 5 includes the Stop Six area. “I hold that same belief for those who will move into the new housing that will replace the previous structures.” l

And yet, those with moderate income can still not afford market rate housing and do not qualify for a subsidy. That crack many fall through is getting deeper and wider.