The setting was apt. In the same Near Southside venue where Jay Wilkinson made his big debut four and a half years ago, dozens of the young painter’s friends and family members had gathered to say goodbye. By next week, the Fort Worth transplant will be a New Yorker. By his own account, Wilkinson had climbed every artistic ladder Fort Worth had to offer, and new challenges were beckoning.

Organized by local talk show host Tony Green, the party at Shipping & Receiving Bar was also a fund-raiser for Wilkinson’s Big Apple adventure. After a two-hour dance party, several of Wilkinson’s artworks were raffled off. Friend Kolin Jardine opened the raffle with a prediction.

“Some turds don’t flush,” he said. “Jay will be back in four months.”

A large cake was brought out in Wilkinson’s honor, and Jardine proceeded to present the large confection using a classic Three Stooges technique that involved foisting said cake onto the guest of honor’s face. Wilkinson did his best to read raffle names through his heavily creamed visage as volunteers did their best to not slip (sometimes unsuccessfully) on the pieces of cake that littered the floor.

“I love you guys,” Wilkinson told the crowd, who responded, “We love you, Jay!”

I caught Wilkinson and artist Brandon Pederson outside. They were excitedly trading stories like two old friends who had not grown tired of reminiscing about their glory days.

Wilkinson said he had just met artist Jeremy Joel, and the next day, “I went to a bar and [Pederson] overheard that I needed to build stuff,” referring to their initial project four and a half years ago, Bobby on Drums, a group show that is credited with initiating the slew of DIY group shows that have followed. Pederson, who had just returned to his home of Fort Worth after five years of living abroad, overheard Wilkinson and introduced himself as someone who can “build stuff.”

“Then we got to build crazy things,” Wilkinson said.

The two friends laughed over their descriptions of a building method they coined “pirate framing.” The improvised technique relies on a blend of knowledge, improvisation, and chaos. They used their 2018 New Year’s Eve event, Ritz & Wonders: The Greatest Show on NYE, as an example. The late-night party featured four life-size elephants that were spread throughout a warehouse in the Foundry District.

“The idea is like, conceive of an image,” Pederson said. “Alright, we have to start with a base, so we build a base. I would hold the board up.”

We were drawing with wood, Wilkinson continued.

“We didn’t know how we would build it,” Wilkinson said. “We were making it up, so it was way sexier.”

After organizing a dozen notable shows and cofounding now-established arts groups like the nonprofit Art Tooth, of which I’m a member, the two friends — along with Joel, who was in California that night — had earned their bragging rights as local pioneering artists.

“I feel like we created a movement, and I’m proud of that,” Pederson said.

Wilkinson was putting the finishing touches on an expansive oil painting when I visited him recently at Fort Works Art, the progressive gallery near the Cultural District. International soul singer and Fort Worthian Leon Bridges commissioned the work a few years ago, and finishing it has been high on Wilkinson’s to-do list before departing to New York City. As the body of B

ob Dylan (one of several iconic musicians Bridges wanted to be included) came into form, Wilkinson noted the incongruous nature of the commission.

“This Leon [commision] is interesting,” he said. “Normally, I don’t have that much data in my work.”

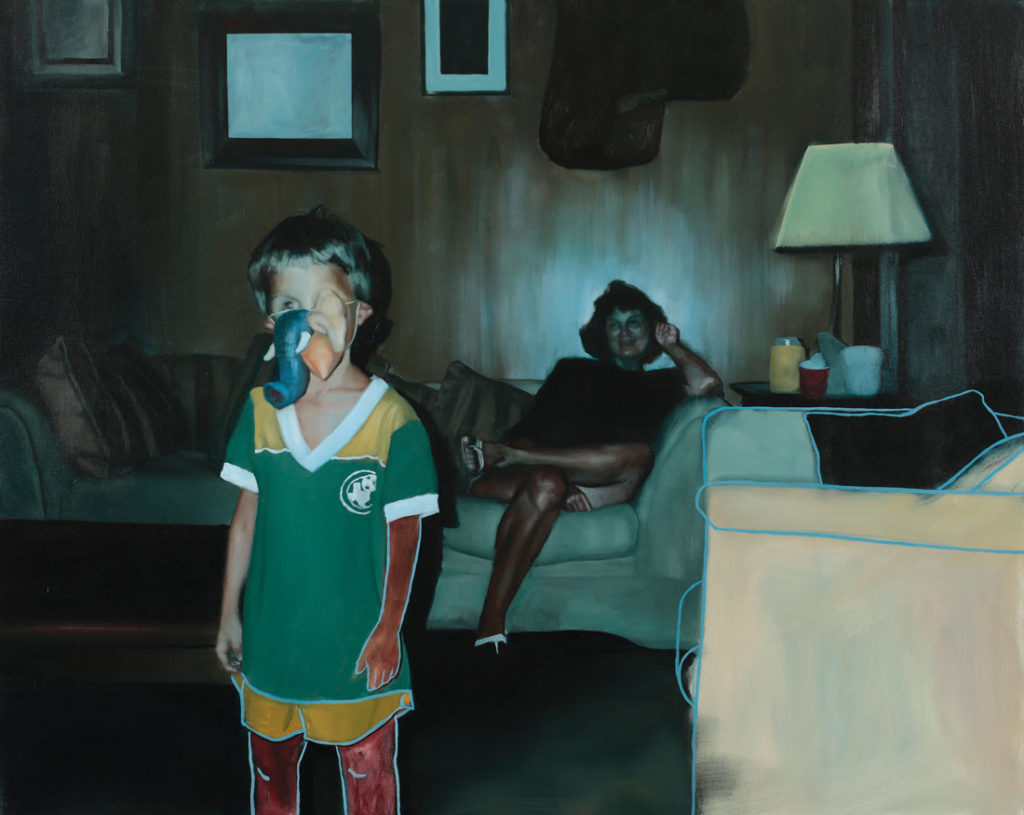

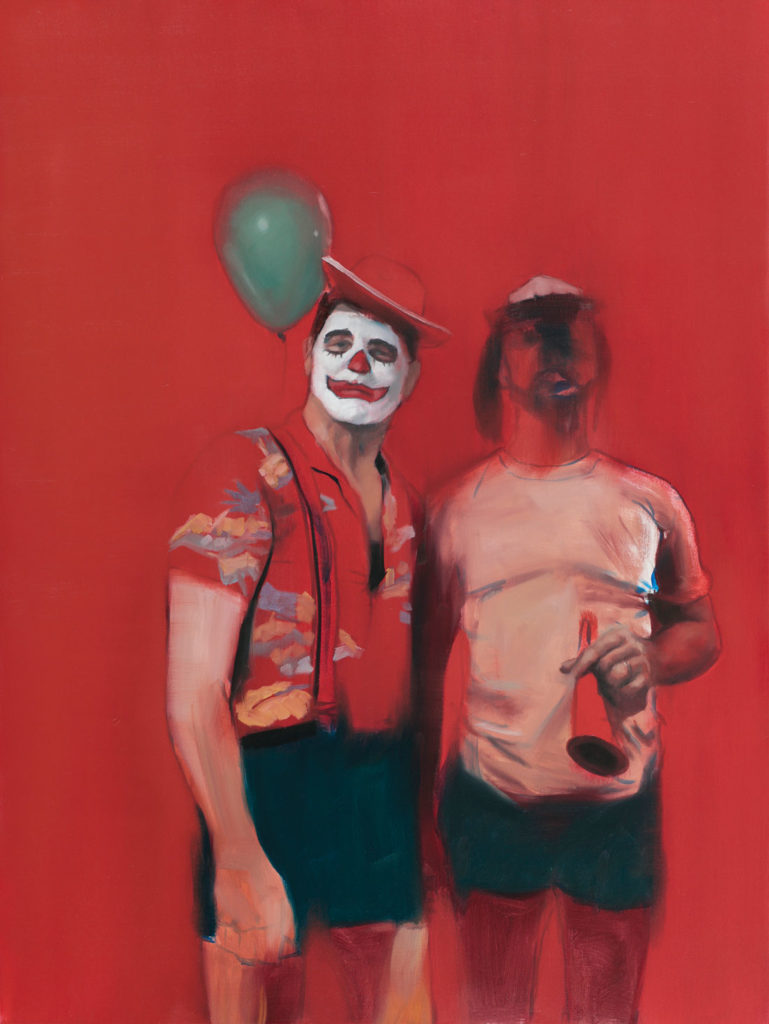

The painter is known for photorealist portraits and scenes that blend hyper-detailed faces or other focal points with blurred color fields that ensure his paintings are never fully grounded in reality.

“It’s never been my thing,” he said, referring to Bridge’s commission. “I might step away from figurative” paintings and explore new possibilities.

Wilkinson was touching on the topic of our conversation: his pending move to Bushwick, a working-class neighborhood in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. Like many people who have come to know Wilkinson — whether as an emerging artist, friend, or that “guy” who built the giant-ass sculptures for ArtsGoggle in 2015 and 2017 — I was curious what prompted the impending move. It was apparent from his pause that the answer required unpacking.

“Moving here 10 years ago [from Portland] was one of the greatest and biggest decisions I made,” he said. “When I moved here, I hadn’t painted in eight years. I grew as an artist here and kept chasing bigger things. I’ve reached the point where I got to work in the best places and with the best people in town. I want to climb bigger mountains. The idea of new markets, moving, trying new things, being broke, being afraid, it’s really important for me as an artist. I thrive in difficulty better than in contentment.”

Few locals would say Wilkinson has been coasting in recent years. His first gallery solo show in 2017, at Fort Works Art, set a high bar for the quality of work that young, local artists can and should be producing. “We will always remain awed by the sweat equity on display and the precise eye,” wrote the Weekly’s Anthony Mariani. “Wilkinson does photorealism one better. Not only is his in-betweenness content admirable –– based on the shapes of the content, it could even be argued that his canvases achieve a sort of abstract-expressionist grandeur –– but he introduces into nearly every scene an eerie aspect of the supernatural.”

Wilkinson currently has several pieces hanging at The Norwood Club, a private retreat in Manhattan which is so exclusive that he had a hard time getting in recently, even as a featured artist. The trappings of outward success have left the painter feeling at odds with his recent paintings.

“It has slowed down my inspiration in a weird way,” he said. “When making work is hard, there’s more beauty in it. That’s why I’ve put off Leon’s painting.”

There’s “weird energy,” he said, that’s injected into the work that doesn’t happen if he’s not under a tight timeline or if he has a “comfortable relationship” with what he’s making.

Taking on exhausting and daunting projects has become a hallmark of Wilkinson’s output. He credits several works and commissions as being formative moments that have helped him grow into the self-assured artist that he is today. Several years ago, he volunteered his time to create an expansive mural in the now-defunct event space the Where House.

“I worked 36 hours straight through,” he recalled. “I wasn’t doing it as my art, but I was doing themed works. I was exercising all of those [artistic] muscles without having to put myself on display.”

Five years ago, Wilkinson formed the art collective Bobby on Drums, which was eponymously named after the 2015 art show that Wilkinson co-curated with Pederson and Joel. Putting together large shows with bands, art, and booze is common-bordering-on-passé today, but at the time, the trio was writing a script that was unproven at best and financially foolhardy at worst.

“That was the beginning of everything,” Wilkinson recalled, saying that he barely knew the owner of Shipping & Receiving, Eddie Vanston. “It was an explosive year.”

Art-themed parties followed on Race Street, a retail/residential strip near the North Side which has a strong art-forward focus. Wilkinson, who turned 30 that year, connected with a new crop of artists who were looking to create opportunities for employees of Fort Worth’s museums. That group, the Exhibitionists, later evolved into the nonprofit Art Tooth, which now regularly partners with Fort Worth’s promotional wing, Visit Fort Worth, and Fort Worth’s museums to create the type of opportunities for artists that Wilkinson has long advocated for. Whether through massive murals or installation works that cause quiet pauses of awe, Wilkinson has taken every opportunity he has been given over the past five years and has surpassed whatever expectations have been made of him.

“It was my blind belief that if I put it in front of people, you can make an impact,” he said. “No one wakes up saying, ‘I want to find an artist.’ You have to put art in front of people. Here it is. Let me put it right in your street and make it easy for you to experience it.”

Artists take creative control over making work, he noted, but they all too often fail to take control over how to put their work out in front of the public. He hopes that, in a small way, the example he set during his time in Fort Worth can guide our city’s next crop of artists. Every project he tackled was done with an eye toward creating the next opportunity, he said. His bold and rebellious approach to art has been largely validated. In 2017, Wilkinson signed a contract that gave him representation through Fort Works Art, whose founder/owner Lauren Childs has also been an integral part of the recent growth that Fort Worth’s art scene has enjoyed.

Wilkinson plans to use his time in New York City to catch up on a backlog of commissions. A well-connected artist friend, Nicole Ofeno, has offered him work building scenic sculptures for Vice Media events, Wilkinson said. There will obviously be opportunities to network, shake hands, and clink pint glasses with the internationally connected network of artists, patrons, and gallery owners that inhabit New York City. Wilkinson’s presence in the Big Apple will be a Fort Worth presence, he said. The artist who has done so much for the local artist community plans to be a contact for groups like Art Tooth and artists who are ready to make their debut in one of the most important art markets in the world.

“What’s missing in Fort Worth are connections to the larger world,” he said. “It’s isolated here. Fort Worth still needs mural projects and private investment in publicly accessible art. We need risk takers who will put up work that is profound and controversial. I’m hoping to be a foothold for Fort Worth out there.”

Five years on, innumerable artists now acknowledge Wilkinson’s role in helping push them toward their current careers as professionals. Three of those creatives gathered outside Shipping & Receiving to recount the impact he has had on their own paths.

Ariel Davis, who joined Art Tooth as Wilkinson was passing that torch off three years ago, is now the gallery manager at one of the most prominent galleries in Fort Worth, Artspace 111. Shasta Haubrich has thanked Wilkinson for showing her that her gift for organizing art events was needed in this city. As communications director for Art Tooth, she now acts as a key liaison between established museums and the broader artist community. Her current focus is on developing a consulting branch for her nonprofit. Pederson, the carpenter who told Wilkinson that he can “build stuff,” is now booked out months in advance for large wood-based projects that blend commercial and artistic sensibilities.

“We were also part of the creation of Jay Wilkinson,” Pederson said. “We built crazy things with him. Shasta was his personal assistant. It was a great thing for the community.”

He deserves a lot of credit, Haubrich said.

“For me, I remember the first 100 for 100 show,” she said, referring to the exhibit by Art Tooth at Shipping & Receiving. “I was doing all the technical stuff for the show. He was like, ‘Oh, my God. Thank you.’ I thought, ‘Maybe I should keep doing this.’ Now, that’s what I do.”

Davis noted the implicit expectations that Wilkinson has set for the city.

“It’s been fun growing up in an era with Jay Wilkinson,” she said. “Jay’s done this. How are we going to respond to his example in a friendly, competitive way?”

The fact that Art Tooth’s cofounder maxed out the opportunities that Fort Worth could offer hints at that task. In a relatively short period of time, Wilkinson’s talents led him from being a bartender to Fort Worth’s artistic Golden Child.

“He topped out,” Haubrich said. “For me, the question is, ‘What are we as artists going to do to make a career in arts sustainable here?’ ”

Wilkinson said the work of Bobby on Drums, Exhibitionists, Joel’s pop-up concept SAM Gallery, and the event space Blackhouse, among many others, has made showing and selling work “a little less bloody” for those who came after. Venues now understand that art shows can pack large spaces, and museums now know that collaborating with smaller art collectives can garner new audiences. Visit Fort Worth sees the stories of local artists as integral to the Fort Worth story and one that draws people to move here.

Five years ago, the idea of several hundred people attending local art shows in nontraditional venues, or “pArty” buses being sponsored by the Kimbell Art Museum, or 30-foot puppets strolling down West Magnolia Avenue would have been anathema to what was expected from our local art scene. Those fanciful ideas are now a commonplace reality, largely due to the efforts of one painter who continually questioned assumptions about what this city was and what it could be. Wilkinson hopes young artists will continue that effort.

“Figure out what you can’t do, what the city doesn’t offer, and try to do that,” he said. “Don’t do the thing that’s easy. If you are doing the same shows over and over, you’re doubling down on the same old ideas. What does this community not have? Go and make that happen. Let’s make this bigger. That’s what our generation did.”