Kenneth Evans doesn’t talk with a lot of people. That’s not surprising, given that he recently was released from home confinement after a 24-year stint in federal prison and 11 months in a halfway house for a 1992 crack conspiracy conviction. Neither does Douglas Dunkins, who did 22 years on a different but similar crack conspiracy conviction. Or Denise Quintanilla, who did more than 17 years on a methamphetamine conspiracy. What binds together these three and several other people from North Texas is that they all got caught up in the legal system during the height of the anti-drug hysteria of the late 1980s and early 1990s, with each of them sentenced as first-time nonviolent drug offenders to life without parole. What also binds them together is that each of them is out now because of something that former President Barack Obama put in place in 2014.

The Clemency Initiative, meant to undo some of the extraordinarily long sentences meted out for relatively minor drug crimes, wound up positively affecting the lives of more than 1,700 people during the last two years of Obama’s term, and most of them are making the best of their second chances.

*****

Evans, 53, grew up on Fort Worth’s South Side. “I was raised by my mom and grandparents” he said, adding that he had two brothers. His upbringing was quite ordinary, he said. “In high school, I was into sports. I played basketball and football and ran track. But after high school, it was hard to get a good-paying job. I worked but couldn’t get one of those good-paying jobs, so I finally turned to the streets.”

He had one brush with the law prior to the crack conviction. In 1986, he was convicted of unauthorized use of a vehicle and received six years probation. “But I stopped reporting in, and then the police got me at a routine stop, and the judge gave me a full year in the [Texas Department of Criminal Justice], state prison. When I got out, the crack epidemic had started, and that was tough.”

Evans’ story is pretty typical from that point on: He started dealing a little crack, which lasted for a few years. A street dealer by his own admission, he was never part of a gang or organization by his telling, just one of a bunch of friends who bought and sold the drug to pay the bills. But that’s not how it was seen by the FBI, which executed a major cleanup of street dealers in Fort Worth in 1992.

“Several of us were indicted on July 28, 1992,” he said. “They charged us with conspiracy and called us kingpins. Heck, we weren’t kingpins. Kingpins had airplanes and boats and brought tons of cocaine into the United States. We were just little guys, but that didn’t mean anything at the time because of the way the sentencing laws operated.”

The federal government enacted harsh sentencing laws in response to several events, including Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No to Drugs campaign, the introduction of crack cocaine (cocaine cooked with baking soda and water) to the inner cities, where it created havoc, the shooting death of a New York City police officer while staking out a suspected crack dealer, and the death of college basketball star Len Bias, despite his death being attributed to powder cocaine and not crack.

Those laws sentenced crack users and dealers to 100 times the weight that powder cocaine users and dealers faced. One gram of crack cocaine earned the same mandatory federal sentence as 100 grams of powder cocaine, despite them being the same drug with the same potency. From Evans’ point of view, “it was all part of Reagan being tough on drugs.”

Evans told me that if the FBI added up the weight of all of the controlled buys they’d made, along with all of the crack that everyone indicted in the conspiracy had on them when they were picked up, it wouldn’t have added up to a kilogram. “But they charged us with 15 kilos, which meant we were sentenced for 1,500 kilos of coke, which was automatic life in prison, first offense or not. Then they added on kingpin status to all of us in the conspiracy, and that meant life without parole. Then they added two 40-year sentences onto me and five more years for a gun I never had. I was 26 years old when I went in, knowing I was supposed to die in there. And almost all of it was for ghost dope, dope that never existed.”

*****

Douglas Dunkins’ story is pretty similar. Born in South Fort Worth in 1965, the second of four kids, the others all girls, he was raised by both his mother and father until they divorced in 1975, after which, he said, things became tough. He started working as a busboy at the Ramada Inn that used to be on South Beach Street while a freshman in OD Wyatt High School and worked his way up to bell captain by the time he graduated.

“After my parents divorced, we struggled,” Dunkins said, “so I had to work to help out as soon as I was old enough. My mother was trying to raise us, and we went without lights, heat, food. And after the Ramada job ended, I struggled and made a wrong turn and got into drugs.”

While his father was always around, Dunkins said, he wasn’t a strong figure, and after Dunkins got into drugs, he stopped listening to his mom. “I was going to do what I wanted to do,” Dunkins said.

The street dealing led to a federal bust in 1992. It was the only mark on his record other than a misdemeanor shoplifting charge for which he received six months probation years earlier. “I was part of a 31-person conspiracy,” he said. “I knew some of them but not all of them. They split us into two groups: the powder cocaine group and the crack group. They offered me five years if I would talk, but I wouldn’t, so I went to trial. I was charged as part of the conspiracy with 20 kilos of crack, was found guilty, and sentenced for 2,000 kilos, life without parole.”

He served at the El Reno medium security federal penitentiary in Oklahoma from February 9, 1993, until August 1, 2016, more than 22 years.

*****

Denice Quintanilla, 50, is a vivacious woman working in Mesquite. A mother of three, she was born in Dallas and raised in Vernon, Texas, and she tells hilarious but sad stories of picking cotton there with her brother as a 9-year-old. “My parents did it too, but it was mainly us kids,” she said.

At 15, her family moved back to Dallas, and other than a three-year stint in Lexington, Kentucky, and Dublin, California, for a cocaine offense, as well as 17-plus years at Carswell federal prison in Fort Worth on a conviction for methamphetamine with intent to distribute, it’s been her home ever since.

“I got hemmed in behind my husband on both my convictions,” she told me. “I married young and promised to do everything to make that marriage work, even after I knew he was a drug dealer. The thing was, I didn’t do drugs. I didn’t know anything about them.”

She might never have been charged in the conspiracy if not for an accident of fate. “My husband left his friend’s pager number at home one day, and [my husband] called me and asked me to page the guy. It turned out the DEA had a wiretap on his phone, and they used that to bring me into the conspiracy. They basically got me for paging someone.”

The conspiracy included 28 defendants, some for marijuana, some for meth. Both Quintanilla and her husband were on the meth side when the groups were split up, and they both got life without parole for 500 grams — half a kilogram — of the drug. Sentenced in 2000, she was released in late 2017.

*****

The Clemency Initiative put forth the guidelines that inmates would need to meet to apply for executive clemency and encouraged those inmates to seek it out, with the promise that their petitions would all be evaluated. According to the Department of Justice website, “the Office of the Pardon Attorney worked in conjunction with the Federal Bureau of Prisons to facilitate the initiative.”

The Justice Department guidelines for receiving clemency — in nearly all cases that fell under the initiative, the clemency came in the form of commuted sentences, rather than absolving the inmates of their criminal offenses — were strict. Inmates had to be currently serving in prison with sentences that would have been “substantially lower” if they were sentenced after federal mandatory minimum sentences were revised downward. The inmates had to have been sentenced to nonviolent crimes and have no “significant ties to large-scale criminal organizations, gangs, or cartels.” Additionally, inmates had to have served at least 10 years of their sentence, have no significant criminal history, demonstrated good conduct while in prison, and have no history of violence “prior to or during their … term of imprisonment.”

It was a high bar to jump. And few inmates knew enough about the law and collecting the necessary paperwork to do it on their own.

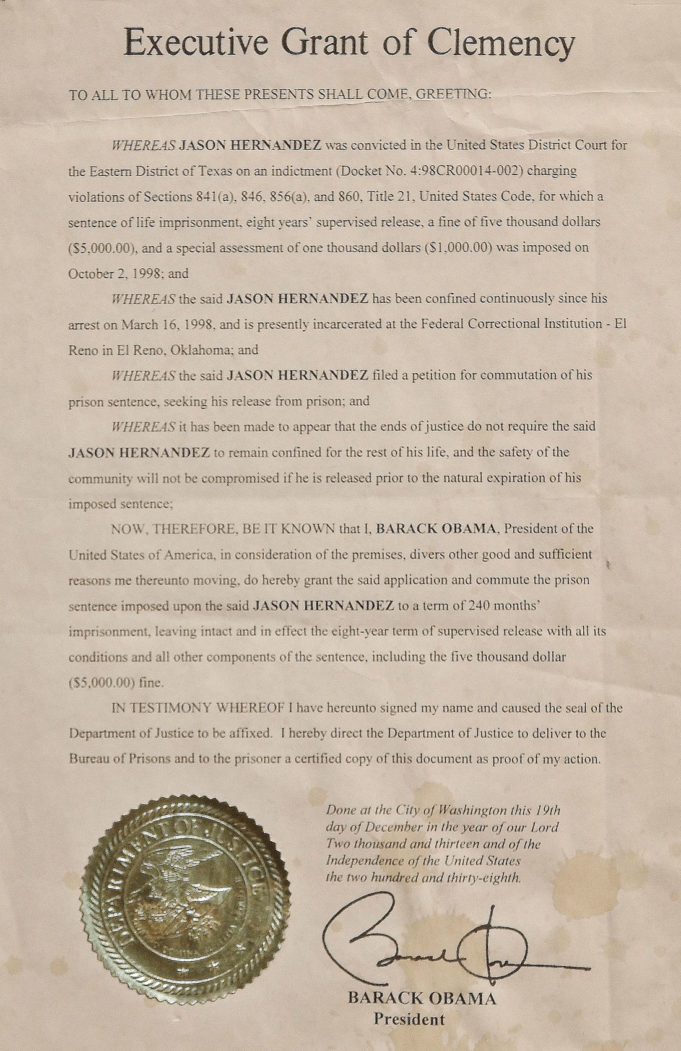

An exception was Jason Hernandez (“Hopeless to Hopeful”, Jan. 16, 2019). He not only successfully managed his own clemency. He helped several other inmates with theirs. He also had at least a small hand in steering the direction a major effort to implement the Clemency Initiative, the Clemency Project.

“The back story,” Hernandez said, “is that I was in the El Reno institution with Douglas Dunkins and Kenneth Evans, and they and some others were good guys. They kept the peace there. They stopped riots. They stopped assaults. They were not in any gang. They just had the respect of the other inmates because they were doing life without parole and they kept their heads up and their noses clean. Kenneth got his GED inside and then tutored other inmates, and for a while he had about the highest graduate rate of any federal prison in the country. And he ran the kitchen. Dunkins ran the inmate law library and got his paralegal certification inside. And I thought it was just wrong that these guys were supposed to die in prison, so my brother [Stevie] and I — he got 10 years for the same conspiracy that got me, so he was out — started a website called Crack Open the Door in 2010. We took pictures and wrote about men and women doing life without parole for nonviolent crack offenses. That same year, a woman named Michelle Alexander, who was a professor who worked with the ACLU, came out with The New Jim Crow, a book that made the argument that our criminal justice system worked just as it did in the Jim Crow era, where minorities were targeted.”

Hernandez said he was trying to push President Obama to grant clemency for nonviolent crack offenders serving life without parole. “My brother and I started writing judges, congressmen, civil rights organizations — almost nobody wrote us back,” he said. “And if they did, they said nobody was going to get relief for life without parole for crack cocaine.”

Hernandez finally wrote to Alexander and told her that her book inspired him. She wrote back that while she thought those offenders deserved a second chance, she couldn’t help. “But what she could do, she said, was connect me to Vanita Gupta, who was with the ACLU and was starting — along with Ezekial Edwards — a new criminal justice initiative. One of the focuses of that initiative was excessive sentencing.”

Once the introductions were made, Hernandez and Stevie, through letters and emails, connected Gupta and Edwards with more than 30 nonviolent crack offenders serving life without parole. “And with that, [Edwards], who was focusing on the long sentences, began to focus on those and others serving life without parole,” Hernandez said. “They came out with a report on November 12, 2013, called A Living Death — Life Without Parole for Nonviolent Offenders. Edwards and Gupta had found over 3,000 of those offenders on the state and federal level while doing that report.”

Hernandez was one of those highlighted in that report, and just a month later, on December 19, 2013, Obama granted clemency to eight of those people highlighted, including Hernandez. “Six were serving life without parole,” Hernandez told me recently. “The other two were serving 30-year sentences. Seven were African-Americans. I was the Latino. Obama commuted all of our eight sentences to 20 years. The other seven had already served the 17 years and eight months needed to be released on a 20-year federal sentence. I had to serve 18 more months to reach that threshold before I was released.”

Four months later, on April 23, 2014, the Clemency Initiative was announced. Edwards, director of the Criminal Law Reform Project at the national ACLU, said that he quickly joined with the American Bar Association, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, and other organizations to create the Clemency Project. “What that project did,” Edwards said, “was recruit and train more than 4,000 lawyers to do a complete screening of more than 36,000 prisoners who requested legal assistance with their clemency petitions, and then we submitted those petitions that qualified for the Clemency Initiative.”

By the time Obama’s second term ended and the Clemency Initiative was no longer in force, Edwards and the Clemency Project had submitted nearly 2,600 petitions for clemency, of which 894 received commutations.

The Clemency Project didn’t work alone, however. Smaller groups also worked with offenders, and the final tally for the Clemency Initiative was 1,794 offenders released, more than 500 of whom were serving life without parole.

Edwards himself worked on Douglas Dunkins’ case. “Douglas is a thoughtful, hard-working person who should never have been put behind bars for the amount of years he faced,” Edwards told me. “Unfortunately, while I think he’s an exceptional person, he’s not exceptional with regards to the many thousands of people who have been put in prisons for extended times unfairly.”

I told Edwards that Dunkins is working hard, is maintaining a rental property he owns where two of his sisters live, and is going to get married soon. Edwards was delighted to hear it.

“I am not surprised that Douglas can stand on his feet and that he’s getting married, even after more than two decades in prison,” Edwards said. “The problem is that there are many thousands of others who remain languishing behind bars who could also be additions to their communities and to their families. Let me note that but for the Clemency Initiative, Douglas would still be in prison until he died. And we have more people facing death by incarceration that any other country in the world, so we have a long way to go to reduce our bloated prison system, to ensure that people like Douglas are not put in the predicament that he was put in.”

Edwards said that the call for clemency that built during Obama’s time in office has waned: “Certainly, the ACLU and other organizations are asking the current administration to establish a regular clemency review process as opposed to the piecemeal way the administration is handling it now.”

(President Donald Trump has given full pardons to 15 people, including those convicted of racketeering, fraud and obstruction of justice, assault and murder, arson, and campaign finance violations, among other things. He has also commuted six sentences, including one for bank fraud and one for bribery, along with one commutation for a woman convicted of nonviolent drug crimes.)

In fairness to Trump, Edwards noted that “with all presidents, clemency and commutations tend to be slow in the first several years of office. What Obama and his attorney general, Eric Holder, did near the end of their terms was sorely needed, and we hope and urge President Trump does something similar.”

*****

All of the people released through clemency in this story are doing well. Kenneth Evans, who works in car manufacturing in Fort Worth, was not released from home confinement — “I had to have breathalizers, call when I was leaving the house, call when I got home” — until May 23, 2019. He remains on supervised release and will be on that for several years unless let off early for good behavior.

“I know I’m out, and it feels good,” Evans said, “but I don’t really do anything. I go to work, come home, go to sleep. I do not want to be out on the streets doing anything.”

Of his time on the inside, particularly at El Reno, he has some good memories along with the bad. “While I was inside, I just read, watched sports, worked in the kitchen, and did tutoring. I even took a class where they taught us to make false teeth.”

And at one point, he said, there was a change in sentencing for certain offenses, “and a form came around that you could fill out to get a sentence reduction. Now there was this white guy — he was in a gang, but we still used to talk — and he couldn’t read or write, but I made him fill out that form in his own handwriting, word by word. And a week later, damn, he got approved. I’ll never forget that one.”

Another time, Evans said, a petition to change a law regarding crack sentencing came around, “and I got hold of it and made 800 copies and gave them to all four units at El Reno and told them to fill them out and I’d turn them in. Some guys asked why should they fill it out if they weren’t in for crack, but I told them this time, it’s crack. Maybe the next time, it’s for what you are in for, so just fill it out. And word about the petition got out on Facebook, and we needed 30,000 signatures and wound up with 80,000, and the sentencing change went through. It wasn’t retroactive, so I didn’t get it, but I was still happy, and I hope I was a big part in that.”

Douglas Dunkins is working as a machine operator and forklift driver in Fort Worth. He bounced around with part-time jobs after he was released but is now on full time and is happy about that. “While I was on the inside at El Reno — I did my whole time there — I used to help people on the legal side of things. I’d also talk to new guys, tell them how to act. Our whole group had life sentences, and people would think we would have no hope and be wild because we had no out date, but we never gave up hope. We didn’t act like we had life sentences. Some guys came in with five-year sentences and gave up and acted stupid and got moved to harder penitentiaries. Our group didn’t do that.”

One of the things that gave him hope was that his mom was battling breast cancer. “She battled that for 12 years and stayed around long enough for me to come home. She passed just months later. But that gave me something to look forward to once I got out. And if my mom could wait around for me, then I had to be a fighter like her. And now I’m having the time of my life. I work to take care of my sisters, and I’m getting married next month to someone who I knew for a long, long time. She waited for me the whole time. It was like she was locked up too.

“There is no such thing as ‘I can’t make it,’ ” he continued. “If Jason and Kenneth and I can make it, everybody can make it.”

Denise Quintanilla lives in Dallas and works at an area hospital as a dietary assistant, as well as working as a cashier for a large clothing outlet. “I am truly blessed,” she said. “I can’t get those 17 years and eight months back, and my three kids missed me every one of those nights. But I was lucky in that I was at Carswell, so they were close. My oldest son moved to Oregon where he’s a manager, so I couldn’t call him daily, but my other son and my daughter and my folks were nearby, so we could visit and stay close. Plus, they were just local calls, and I could afford those from the 40 cents an hour I was making in the facility’s office. Plus, I made blankets and crocheted things for people, things you’re not supposed to do but that I had to do to survive and have money for the calls and things like shampoo. Heck, I did people’s laundry, I ironed it, whatever was necessary to survive without asking my family for money. They were not the ones who put me in there.

“Reentry is tough for everybody,” she continued. “That’s why I work two jobs. But if I have to work three jobs, I’ll do it. And since I’ve been out, me and my brother have relocated and connected with my real father. It’s been amazing. I went from having two brothers to having seven other siblings, and I’ve met them all. I am very glad to be out.”

As for Hernandez, he has another year on a Soros Justice Foundation grant, and he keeps working at getting others out, teaching them how to file the right paperwork and who to contact and helping them keep some faith that their turn will come.

“We still have a lot of work to do,” he told me. “There are thousands of people still inside serving life sentences for nonviolent crimes and we — that’s all of us who think a change is needed — have to keep working until that is no longer the case. It’s a worthy fight.”

And the hypocrisy of politicians passing draconian laws for sentencing first offenders when their own kids are often out buying their drugs on the street

Very unfortunate and cruel that one’s dreams for the future can be crushed in a moment just for some stupid mistake that only requires momentary correction.