There have been comedies about martial arts, but I can’t recall a previous one about how a master’s demand for loyalty and discipline, abetted by Eastern philosophy’s emphasis on submission to authority, can build up a cult-like atmosphere around him. (It’s always a him.) As it happens, writer-director Riley Stearns’ debut feature, Faults, was about a religious cult. He pulls some tricks from that film in his new comedy The Art of Self-Defense, but this is a marked improvement over his maddening first film. More than that, it’s a sour, subversive treat that’s opening this week at various local theaters.

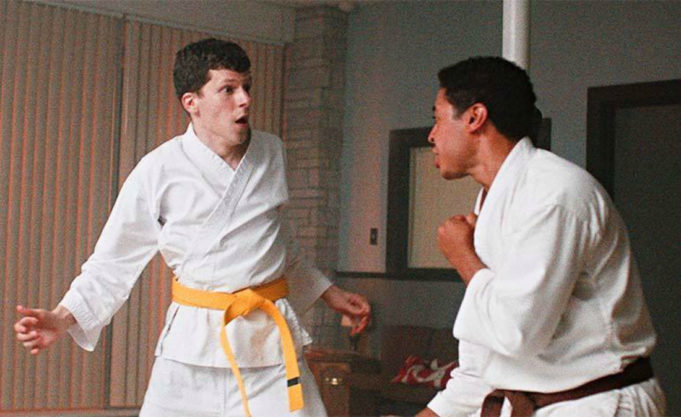

Jesse Eisenberg plays Casey Davies, a meek, solitary 35-year-old accountant who goes out one night for groceries and is brutally assaulted by five dudes on motorcycles. In response to this, he tries to buy a gun, but instead takes a detour into a karate dojo and falls into the worst hands imaginable: a nameless, humorless, overly intense sensei (Alessandro Nivola) who immediately notes that Casey’s name is too feminine for a man. He does not ask Casey to change his name, but he does find manlier substitutes for Casey’s favorite music (adult contemporary) and foreign language (French), and teaches him that weak people should be preyed upon. Admitting to being scared all the time, Casey is only too happy to listen, saying, “I want to be what intimidates me.” After some progress in Casey’s training, the master points out a random guy at a bar and tells him that it’s one of his attackers, which results in the poor drunken bastard receiving a serious head injury.

The script could perhaps be finer in its satire of alpha-maleness, but it’s helped immensely by Nivola’s performance, which nicely straddles the line between funny and creepy. On the one hand, he straight-facedly spouts absurdities such as, “I will teach you to kick with your fists and punch with your feet.” On the other, he shatters a student’s arm over a minor rules infraction. His endless glorification of a masculine ideal shortchanges Anna (Imogen Poots), the only woman among his advanced students. She’s clearly the best fighter, so when she’s passed over for a black belt in favor of a male colleague (Steve Terada), she responds by challenging him to single combat and then beating him into unconsciousness and beyond. (Afterwards, she turns to Casey with blood splattered on her gi and says seriously, “This place isn’t safe.”) Though the sensei approves of her actions, he confides to Casey that he’ll never give her the black belt she craves, saying, “Her being a woman unfortunately prevents her from becoming a man.”

Eisenberg is perfectly cast as a defective beta male who sobs uncontrollably in his car after backing down from a physical altercation. Eisenberg’s performance — and Stearns’ delirious treatment of the scene — conveys the rush of accomplishment that Casey feels when he first lands a kick to the face of a brown belt and knocks out one of the guy’s teeth. Casey comes to believe that violence is the way to attain manhood, and when his boss (Hauke Bahr) gently suggests that he start work on expense reports, Casey punches him in the throat, an act that both gets him fired and instantly wins him the respect of his disgusting male co-workers.

Stearns mostly films this in a flat, affectless style that recalls Napoleon Dynamite. However, instead of the cutesy hijinks of that film, this one uses the style to depict an environment that’s spiraling into chaos, as Casey’s investigation into the business’ accounts and equipment room reveals that no one ever really leaves this dojo. In a delicious twist, Casey prevails over his master not by suddenly becoming woke but rather by twisting the sensei’s hyper-masculine wisdom to his own ends. The film climaxes with multiple deaths, and the alarming passivity with which the other students accept this is part of a motif here. The master has intentionally populated his dojo with weak people who want a strongman to tell them what to do, and while Casey creates a path to more enlightened leadership, he does it by taking advantage of the others’ weakness. In the end, what good are martial-arts skills if acquiring them turns you into a mindless thug? The Art of Self-Defense ends with Casey teaching the dojo’s children’s class, which is just the disturbing happy ending that this movie warrants.

Starring Jesse Eisenberg and Alessandro Nivola. Written and directed by Riley Stearns. Rated R.