About a year ago, while setting up the bar for happy hour at Off the Record, the cocktail bar/record store situated in what I think of as the “Middle East” of West Magnolia Avenue – those blocks between Alston and Hemphill streets –– I chortled heartily after gazing out the street-facing windows and witnessing a little kid kick a slightly bigger kid square in the balls, in retaliation for the latter pushing the former off his bike. A grown-up intervened before that sequence launched a full-scale brother-brawl, and before long, both zoomed back into the unstructured pedestrian traffic patterns that had arisen around an ad hoc soccer pitch designated by a pair of child-sized goals set up in the middle of the street. Within the boundaries of the goals and some parking cones, little kids busily chased and booted soccer balls, and as noon rolled around, the street and sidewalks thronged with parents, children, and dogs basking in the fun of a gorgeous early-spring Sunday.

This was Open Streets 2018, when Magnolia was shut down between 8th Avenue and Hemphill for this annual play-day, where the neighborhood’s residents and people from all over the city celebrate the joys of outdoor activity for the bulk of the afternoon. I watched a couple pushing a baby in a stroller stop to fix their dog’s tangled leash, and I instantly regretted and resented having to work, because by the time my shift came to its conclusion, Open Streets would be over, and I would thereby miss watching the skate jam.

Since 2011, this ever-popular event has been run by Near Southside, Inc., the nonprofit devoted to the area’s wellbeing. Per its own marketing copy, “Open Streets is a community play-day dedicated to neighborly interaction, healthy activity, and complete streets awareness,” in which “non-motorized rolling fun – i.e. bikes, boards, roller skates, and scooters” are the permitted forms of transit, and outdoor activities ranging from martial arts and yoga to obstacle courses and breakdancing are celebrated and encouraged, with a spattering of locally made artisan booths and food trucks, with preference given to Near Southside residents and business owners. But by design, the sales-y street festival component takes a backseat to the physical activity. Yes, you can buy a street taco and a crystal pendant on a handmade necklace, but hopefully you’re skipping on your way to the vendors.

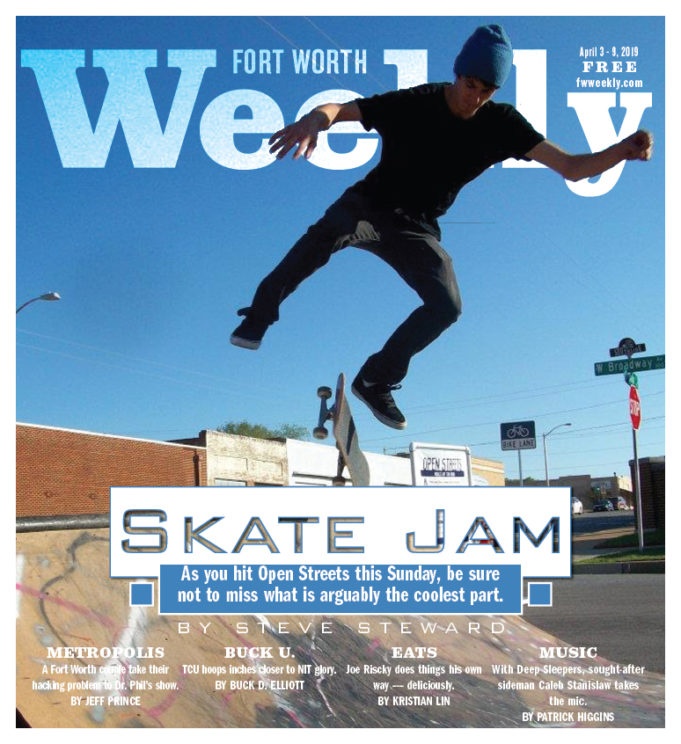

Open Streets is obviously fun for families and dogs and everyone else who loves to play outside, but for Fort Worth’s skateboarding scene, it’s basically the high point of the year. Since the launch of the event, the west end of Magnolia has turned into a mini skate park, and each year, more and more skaters roll up to ride its ramps, rails, and ledges, all of which are built by a handful of dedicated DIY-minded members of the Near Southside’s skateboarding community. Whether you think of skateboarding as a sport, hobby, or lifestyle, it is defined by its notoriously individualistic spirit, and, as such, it stands to reason that getting a bunch of characters bearing that sort of personality streak to come together and build something like the Open Streets skate jam might be a tall order. But that’s precisely what happens. According to lifelong skateboarder and longtime Near Southsider John Shea, coming together as a community to support the skate scene is kind of what being part of that community is about. Though he is imminently humble about his own contributions to skateboarding in this city, Shea, along with friend Luis “Louie” Perez and a handful of other “OG” skaters, are the driving force behind what is arguably Open Streets’ signature component.

*****

Other than rolling fearfully down the driveway when I was a kid and some beer-addled longboarding aspirations in my late 20s, I never really got into skateboarding, but I did grow up in the ’80s and went to high school in the mid ’90s, when board culture was always in my periphery, first with friends’ older brothers popping Powell-Peralta’s iconic Bones Brigade videos into VCRs at sleepovers, then later, watching other kids bang around the parking blocks and curbs in the parking lot after school. If I had grown up here, John Shea and Louie Perez would’ve been some of those kids. Over beers at a local Magnolia bar recently, Shea told me he saw his first board in 1986. For Perez, it was ’84.

“I was into breakdancing when I came into skateboarding,” Perez said. “My cousin rode through our apartment complex on a Nash board, a Nash Fly-Me. He had started breakdancing before me, and I looked up to him, so I started doing both.”

Perez is 46, so he’s been into skateboarding for something like 35 years, and for Shea, now 42, he’s been riding a board for 33.

With 68 years of skateboarding between them, Shea and Perez have learned a lot of tricks and techniques, and while mastering the moves, slides, jumps, and airs – and enduring all of the slams and injuries that are parceled with the experience – have made the guys somewhat locally revered, their acquired skills with drills and hammers are what have really made the Open Streets skate jam possible on a practical level.

“I learned how to build stuff,” Perez said.

Skateboarding has always piggybacked on punk rock’s DIY ethos, but back in the ’80s and ’90s, it had more to do with practicality than with ideals or aesthetics.

“Back then, the only time we could go to a skate park, we would go to the Jeff Philips skate park in Dallas or maybe Skate Time at Bachman Lake,” Perez said. “Being a teenager, it was kinda hard to get your parents to drive you to Dallas to go skate, so we started putting ramps together. I lived in Everman for the longest time, and we had one guy who knew how to build stuff, who showed us how, this guy Tony Burkett. He always had mini-ramps in his backyard. He lived in Rendon, out in the country … . He showed me how to build ramps. I bought a ramp someone was selling for $75, but it was just a big pile of wood. It had transitions cut out, but it was a build-it-yourself thing. And I asked him if he could help me build it, and he said, ‘I’ll show you how to put it together.’ And so he showed me how to do it, and I’ve been building stuff ever since.”

Last year, Perez’s pièce de résistance was a huge box ledge painted to look like, well, a box, specifically one that might have held the world’s biggest pair of Adidas. But over the past eight years, he and Shea have both built and stored on their own dime and at their own homes a veritable showroom of ramps and transitions, which the guys and friends haul from Shea’s house on nearby Hurley Street down the block and set up in the morning of each Open Streets. As you might imagine, it’s a ton of work to fill a city block with the kind of obstacles and transitions that skaters actually enjoy. But perhaps more remarkable is that Shea and Perez took all that work on themselves from Day 1, when one of their friends, a skater named Brighton Grisel, saw the first Open Streets flyer.

“They put the posters up that said, ‘Open Streets Happening’ with the date,” Shea said, “and on the poster, it said, ‘Dog-walking, biking, and skateboarding.’ There were no plans for what the skateboarding would be, just that people would ride their skateboards up and down the street, and that was it.”

“And that’s where Brighton came in,” Perez said. “He saw the poster and brought it to me, and he said, ‘I’m gonna find out who to talk to,’ and he poked around,” which brought him in contact with two leaders of Near Southside, Inc., Mike Brennan and Megan Carroll Henderson.

For a couple of skaters, the opportunity to be given carte blanche by a city-approved neighborhood nonprofit to make up a skate park-esque situation was more or less a dream come true.

“We stood there on the corner and said to [Brennan], ‘Ramps?’ ” Shea recalled. “And he was like, ‘Well, where do you guys want to set up?’ And I said, ‘How about right here, at the end of my street? Make it easiest to drag stuff down.’ It was basically me, Brighton, and Louie for the first three years setting up ramps.”

Perez built some quarter pipe ramps and a ledge, and his friend Erica Duquesne painted them. Shea and Grisel built the “Fish Ledge,” a 6-foot horizontal spine joining a pair of angled boards painted with a couple of aquarium plants and a goldfish

“It’s the one obstacle that’s been to every Open Streets,” Shea said. “It lives on my porch.”

Like every beginning, Open Streets’ skateboard event started small, but momentum built quickly, especially since Open Streets was held twice a year (spring and fall) from 2011 through 2014.

“At first,” Shea said, “it was like seven of us neighborhood skaters, like, ‘Haha, the city let us shut down the street and drag some ramps out there for a few hours.’ And we felt like we were getting away with something as much as we were helping the event.”

But then it grew bigger and bigger. Shea said the Near Southside has seen a “rotation of skaters” that have moved in and out of the neighborhood over the years, but there are always new ones who help out. Shea said that one local business was a direct byproduct of Open Streets’ skateboard component.

Magnolia Skate Shop, an independent business retailing skateboards, accessories, and apparel, is co-owned by local skateboarders Bobby Wilson and Coyt Caffey. According to Perez, they opened their outfit on that stretch of Magnolia because of Open Streets.

“That’s exactly why they put the shop here, because of the event we have every year,” he said.

Per the shop’s for-skaters-by-skaters business model, it’s highly supportive of the scene.

Wilson, Shea said, has been “really cool about saying why he opened his shop on Magnolia. I met him like two-and-a-half, three years ago through Index Skateboards and this video screening thing they had. We had mutual friends in the skate scene.”

That happenstance networking is pretty much intrinsic to the skateboard community –– Perez’s Facebook page is full of nostalgic pics from Freestyle, the Kennendale skate park he ran until it closed in 2009, and in those photos are the teenage versions of many of the same faces you see turning up to grind on the Open Streets transitions.

*****

Being skateboarding lifers, Perez and Shea have both found employment within the sport. Prior to running Freestyle, Perez worked at M&M Skate Park in Austin for five years. Shea moved to Southern California in 1999 and spent five years working for Dwindle Distribution, the largest skateboard manufacturer in the world, before moving back to Fort Worth in 2004. After he returned, he landed a job at Spiral Diner and a house on Hurley.

“I fell in love with this neighborhood,” he said.

Magnolia’s boom didn’t really ignite until about 10 years ago, and before that, the street was pretty empty – a perfect environment for someone like Shea, who said he’d spent his time in SoCal living and breathing skateboarding. Naturally, he wanted to help grow the scene here however he could. Back when I dabbled in longboarding, I went to a couple of meetings at a local nonprofit space for a group that tried to encourage the city to build a concrete skate park. Most of the people were younger than I was (and employed at Spiral Diner), but there was a tall, lanky guy in baggy jeans who seemed to be about my age. I found out later that was Shea.

Shea has been an advocate for Fort Worth’s skateboard culture for years, and though he probably would politely decline to take credit for it, Open Streets has been his biggest success in that endeavor. But Shea sees it not as some victory but more of a positive movement and a way to give back to the greater community.

“Open Streets is a way to share, honestly, to shine a light on what would happen if you just let us get away with stuff all the time,” Shea said, “or if there was a [skateboarding] spot [on the Near Southside] where we could drag this stuff out all the time and maintain it ourselves or get an actual legit concrete park. Me and Louie both, off and on for years, have been going to meetings with the city about getting a concrete park. We carried an interest group all the way to the point where there was a ribbon-cutting ceremony at Gateway Park for construction on a concrete skate park, but that never ended up happening. It was on the books and a poster hanging at the dog park showing what it was going to look like, the skate plaza. And it just fell apart. The city doesn’t want to fund it. As far as what I’ve heard, there are like five skate parks that are approved to get built in the area, but they’re never gonna be able to fund any of them. Within 150 miles of here, there are like 10 good parks, but there’s not a great one in Fort Worth.”

He and Perez do note that there are a couple in-city parks that are either a token effort (Marine Creek Park) or frustratingly distant. Marine Creek, Shea said, is “a pre-fab park that people who don’t skate sort of just threw together. They spend money on these drop-ins, but you’re not gonna build a scene there.”

Perez believes a concrete park could happen with help from Skatepark of Austin, which built Chisolm Trail Park in Crowley.

“Chisolm Trail is a good park, but it’s kind of far away,” Perez said.

*****

Money, like the song says, is a drag, at least when it comes to funding a park and, for that matter, when you’re a skater who wants to build ramps for an annual community event. Shea, Perez, and friends like fellow skater Evan Owens have all constructed Open Streets’ skateable topography out of their own pockets, occasionally supplementing their funds with donations and/or benefit events. But strictly speaking, the event is borne out of their passion for the sport, and it’s also borne out of a little bit of hoping for the best.

“It’s a leap of faith,” Shea said. “Like if the weather doesn’t work out for it, then all that work and money is kind of gone until the next one. You have the ramps until next year, but keeping them and storing them is another thing.”

That leap of faith has not gone unnoticed, nor has it gone unheralded, at least. Megan Carroll Henderson, director of events and communications for Near Southside, Inc., is sincerely effusive of Shea’s contribution to Open Streets.

“John was one of the very first people to offer to be involved with the event,” she wrote in an email. “Most importantly, he has always been dogmatic that he never receive credit, that no single company or product ever have ownership of the skate jam. Skate jam has been and always will be built by the community and for the community. But mostly, it’s built by John. His passion, selflessness, and dedication to the sport, his understanding that more than a sport, it is a community, and more than a community, skating is an act of family to provide refuge and acceptance to those in need.

“Shea spends countless hours, endless dollars of his own money, and nearly every square inch of his backyard preparing the materials for skate jam. In years past, he didn’t have so much as a dolly to roll the ramps down the hill from his house, so he’d put everything on four skateboards and roll it down the hill with the help of a few friends.”

Indeed, while Shea happily agreed to an interview about skate jam, he downplayed his involvement, as did Perez. They are both really just focused on how it exists because the skaters want it to, but Shea asserted that it is all about the skateboarding community and not owned by any other entity.

“Open Streets is an evolving thing,” he said. “It started out as goofing off, and now a lot of people want in on it, or want a piece of it, or want to promote their own stuff through it, but it’s still just a skate jam, run by skaters from the neighborhood. It’s been tricky to keep it ‘in the car’ because it’s an event inside of an event for Near Southside –– Open Streets isn’t my event to begin with, so how can you blow it out and get the sponsors for an event that’s part of another event that you’re supposed to be supporting?”

Yet even he and Perez will allow that their event is one of Open Streets’ main draws.

“We’ve been told we are essential to it,” Perez said, chuckling.

Yet Shea can’t escape some recognition.

“Two years ago,” Henderson wrote, “we had the great privilege of honoring John Shea at our Near Southside Shindig Dinner in front of 900 Near Southside community members by recognizing him as our Most Valuable Partner with an award. He’s kind, generous, [and] sincere. And he cares so deeply for the community. John Shea is a reminder of the spirit of this neighborhood, the way in which we all take care of each other and that we can do something for others with no credit or photo, no Instastory or front-page cover of a magazine.”

Shea, along with Perez, is literally the subject of a front-cover story at this very moment, though that status is arguably in the service of his passion for putting together the skate jam. And when I talked to him and Perez, at the beginning of March, about a month ahead of the event that starts at noon on Sunday, they were still scrambling to put all the pieces together, in part due to the crummy weather that fell on North Texas at the time. Perez said he was going to “freestyle” a ramp.

“I have the wood, but I’m wracking my brain trying to come up with something,” he said. “Last-minute shit is fun.”

Shea laughed: “Open Streets comes together one way or another every year, and all the planning in the world can’t prepare you for that last push during the week before it happens. I’ll take responsibility for hoarding all these ramps and stuff at my house and letting it more or less run my life for the past few years, but the day of Open Streets, it takes all of us. It’s like 100-hour setup for a four-hour event. It’s a labor of love, and the key word is that it’s a lot of effort. My back is killing me –– I was 34 when this started.”

But even though his back and knees complain and he and Perez are both nagged by the ghosts of three decades of skateboard-related injuries, Shea is still stoked.

“It’s always worth it to show up for skating, though,” Shea said. “As long as there are people around here who love it and want to help out and make the events happen, just do it for skateboarding, it’ll always be this sick neighborhood event.”