This weekend, I put some work into trying to help my niece show her value to college coaches. Our presentation focused on traditional attributes like athletic achievement and academic excellence (and, by the way, if you’re a college volleyball coach in need of an outside hitter, I can help you).

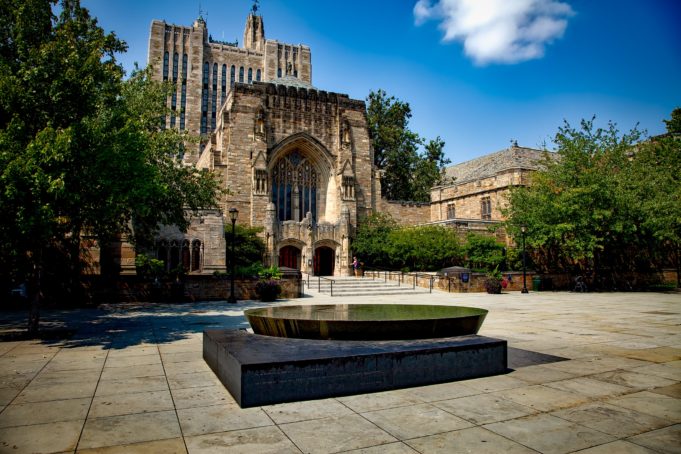

My dad made a joke about no longer being able to buy her way into Yale, thanks to the revelation of widespread incidents involving, among other things, coaches bribed to help applicants pose as athletes to ensure their acceptance to prestigious schools. Since neither my father’s sense of ethics nor his net worth would accommodate under-the-table payments, his granddaughter will have to earn her way into educational opportunities beyond high school.

But this scandal got me thinking – why? Why would rich people have incentive to bend rules and laws to pay large sums to get their kids into to-tier schools? And why was the system susceptible to the scheme?

Most people want the best for their children. And getting them an Ivy League-level education would seem a laudable goal. That doesn’t mean they should bend moral principles to do it, certainly, but we do need to ask why they felt they had to.

There’s a lot of perceived (and probably actual) value in having a degree from an elite university. So why can’t everyone who can afford it get one legally?

Some of the scarcity is natural. Only so many students can physically attend any one school. Also, one can’t simply create 300+ years worth of reputation (e.g. Harvard was founded in 1636, Yale in 1701). And to the extent that having the name of the school at the bottom of the degree matters in and of itself, such institutions have a built-in edge over competitors. Such an advantage counts double when it helps the career prospects of a prospective student and buffs a parent’s sizable ego.

Usually when the quantity demanded of a scarce good exceeds the supply, entrepreneurs react. We see challenger companies take on entrenched brands all the time, even in the high-dollar luxury goods space. Lexus, Infiniti, and Acura, for instance, successfully carved out niches competing with the venerable Mercedes, Cadillac, Lincoln, and Jaguar nameplates in the 1990s. But among the schools implicated in this scandal, only the 70-year-old University of San Diego has been around less than 100 years. Each year, elite colleges turn away thousands upon thousands of applicants who believe themselves qualified to receive this country’s top academic experiences. Yet no competitors have emerged to cater to these students (especially those with well-to-do parents) and try to out-Ivy the Ivy League. Why?

For-profit colleges don’t market themselves as top-tier, often catering to students who need flexibility and open admissions to accompany their educational experiences as opposed to hallowed halls, endowed professorships, and Saturday tailgating. They must not think they can compete for the students whose parents can afford to provide them with traditional higher education.

Two key factors contribute: endowments and tax dollars.

The old-school private schools have been around long enough and produced enough wealthy alumni to have accumulated a substantial supply of donated buildings and hefty endowments.

States finance loads of post-secondary schools, too. They receive donations, but also get an infusion of tax dollars to subsidize their operations.

And, speaking of taxes, donors can deduct their contributions to any of the above.

It’s tough for any startup to compete against huge established firms, much less those with state-sponsored advantages. And whenever the state restricts the supply of anything, from cigarettes to booze to, in this case, super-premium education, a black market will emerge.

But that also gets one to thinking – there are clearly people willing to pay massive amounts of money to get their children into a certain type of school – is it possible to provide it without having to resort to what is basically admission smuggling?

You’d perhaps have to duplicate many of the features of a traditional education, like broad-based programs, Greek organizations, and intercollegiate athletics (the Big 12 could use a couple more teams). Like most businesses, location might matter – perhaps one could repurpose a disused corporate campus in an attractive metropolitan area. And you’d have to figure out a way to combat tradition with trendiness – attracting the children of celebrities couldn’t hurt.

For-profit educational institutions can still receive federal grant and loan dollars, so they could keep accepting exceptional students of all income levels. And a for-profit institution can be very upfront about whether they’ll give special admissions consideration to those who can pay the full tuition amount. Better to have it that way than to have illicit payments ending up in the pockets of the Rick Singers of the world. Much of the angst about this dustup has come from the idea that qualified students without the coin for bribes got denied their rightful place in these student bodies. If the rich people have somewhere they deem acceptable to send their kids, those borderline applicants benefit.

While athletics got caught up in this imbroglio, it’s not the concept of special admissions privileges for those with special skills (including not only setters and midfielders, but sopranos and playwrights, too) that’s at issue. The issue is one of unethical behavior by a few individuals and the lack of alternatives that made it so lucrative.

I feel like this gives my niece an advantage, because she’s a real actual volleyball player (made the conference all-tournament team twice, just sayin’) with some quality academic credentials. She should benefit from the enhanced scrutiny of candidates sure to result from this scandal. It would be nice if the whole marketplace for education did as well.