Photorealist precision paired with nuanced strength. Those are the evocative hallmarks of the 23 drawings by Marshall Harris in I Wanna Be a Cowboy, the Fort Worth artist’s first-ever exhibition at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center.

Joining a series of other FWCAC shows with Western themes, Harris’ works underscore his place as one of Texas’ most dexterous and meticulous photorealists.

This show also serves as harbinger of new creative directions for Harris, as he ventures into more abstract territory with his Western-themed subjects while also injecting a bracing new palette of psychedelic colors into what have been his signature monochromatic works.

Anyone even remotely familiar with Harris’ work – which he has produced prodigiously since the TCU alum and former NFL defensive lineman returned to Fort Worth in 2010 – will greet this show with a contented smile, as it showcases his well-established talent for creating photo-quality images of two of Western ranch culture’s greatest totems: the saddle and the sun-bleached skull.

Harris’ saddle works are presented on such a relatively large scale (some measure 5 feet wide by 6 feet tall) that he treats them as grand homages to functional art. Using his medium of choice – graphite (often 18 different grades of graphite pencil) on Mylar (the engineer’s preferred synthetic paper) – Harris creates dynamic pieces that range from black to white with countless shades of gray in between.

Harris invests each object portrayed (often a saddle) with its own weather-beaten history, as every scuff, dent, scratch, and rope burn denotes an aspect of the object’s craftsmanship. Harris desires nothing less than to chronicle the scars of a saddle’s demanding prairie life.

These wrinkles of age and use are particularly visible in his depiction of the 1920s-vintage “Fancy Frills” saddle from San Angelo’s M.L. Leddy shop. Those deeply grooved character lines are also displayed in other saddles as “Paper-Boy” and “Round-Up,” the first saddle Harris ever drew. On “Round-Up,” Harris reproduced on the saddle’s “fender” a cowboy lassoing a calf, an unmistakable clue to the main occupation of this rancher.

Ironically, the Harris work that has taken on virtual icon status is not a saddle. Rather, in “The Hand that Feeds” (the show’s largest work at 54 inches tall by 110 inches wide), Harris fixates on the ornate tattoo running up the forearm of Gino Rojas, owner of the relocated Revolver Taco Lounge. Harris formed an artistic bridge between Rojas’ tattoo and the gold scrollwork inlayed into the pistol he’s holding.

The series 9, which occupied Harris for 18 months, has the artist positioning a single cat skull in nine different positions, with varying degrees of shadow and light draping it. While Harris’ signature attention to minute detail is on display in his replication of every crack and crevice in the skull’s contours, he adds greater three-dimensional depth of field to each skull by portraying its front with great crispness, while its back is fuzzily out of focus.

Nowhere in the exhibition is Harris’ new melding of abstraction with his trademark photorealism more evident than in “Spurs Parts #1 & #2.” Using what he terms a “negative drawing process,” Harris created a photo-negative effect of the spurs. Everything is, as in a classic photo negative, the reverse of the object’s natural color scheme: Black is white; white is black. At this point, with the work resembling a medical X-ray, with areas of lurking shadow and soft-focus blurriness, Harris couldn’t be further removed from his comfort zone of photorealism.

Paradoxically, Harris’ new abstraction, with its blend of clear and soft focus, achieves a more convincing three-dimensional realism than even his two-dimensional, surgically detailed drawings. At this point, Harris’ “Spurs” transitions from abstraction to his more familiar territory by scanning the work before “inverting” it to arrive at the original object: an antique spur – now seen with Harris’ customary clarity.

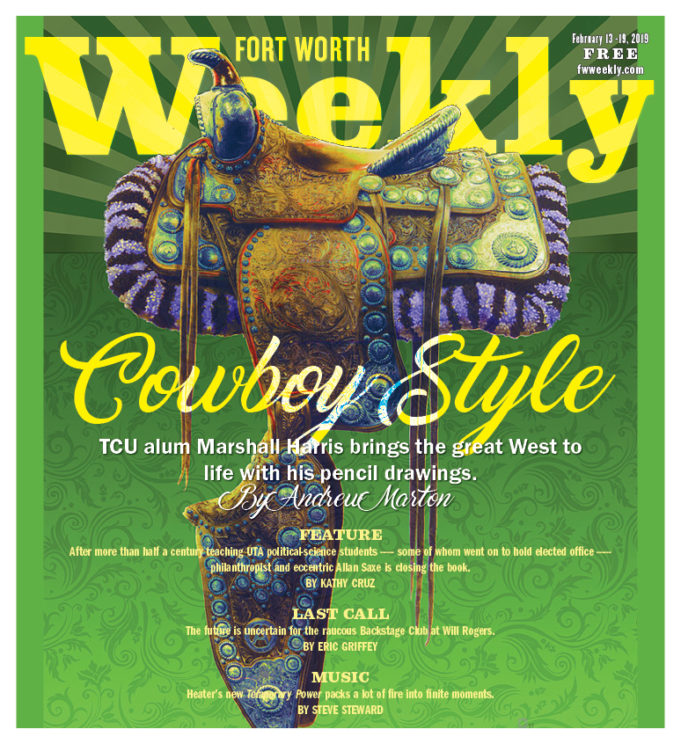

In perhaps the most striking departure from his usual approach, Harris has, in a series of three psychedelic saddle works, infused his original monochromatic saddles – “Fancy Frills,” “Round-Up,” and “Paper-Boy” – with everything from an electric-green backdrop and purple-tinted fur bordering the saddle to bright, chartreuse accents on the silver tooling.

By applying digitized, trippy shades of opal, chartreuse, and burnt umber on what had been a classic tan saddle, Harris is clearly having loads of fun converting a traditional saddle into something that might glow in the dark in some hippy lair.

Given that Harris often takes about 350 hours to create just one saddle work, this show offers a glimpse into the amount of sweat and perhaps a few tears required to achieve his level of precise detail. Harris’ near-obsessive attention to every nook and cranny of these quintessential Western objects becomes a contemporary close-up of the Panavision-wide depiction of Western life portrayed by masters Charles Russell and Frederic Remington.

What this exhibition reminds you is that while Russell and Remington adopted a mountain bluff’s vantage point on Western life, Harris works in painstaking close-up, giving us a rare window into the unexpectedly ornate beauty of some essential objects of Western ranch life.

I Wanna Be A Cowboy,

by Marshall Harris

Thru Feb 20 at the Fort Worth Community Arts Center, 1300 Gendy St, FW. Free. 817-738-1938.