Fake news! Enemy of the people!

We’ve heard these claims against the mainstream media a thousand times from the current occupant of the Oval Office, but accusations of liberal prejudice in the press have been around for decades. They can be traced back to the 1971 publication of Edith Efron’s The News Twisters, in which she claimed to have found bias in the television news coverage of the 1968 presidential contest between former Republican Vice President Richard Nixon and Democratic incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey. The notoriously paranoid and press-hating Nixon, who won election and re-election but later resigned due to the Watergate scandal, ordered his White House special counsel, Charles Colson, to get the book on the bestseller list, according to an interview Colson did with Newsweek in 1994. Over the past three decades, the rise of conservative talk radio has provided a megaphone that has kept the liberal bias charge alive and well.

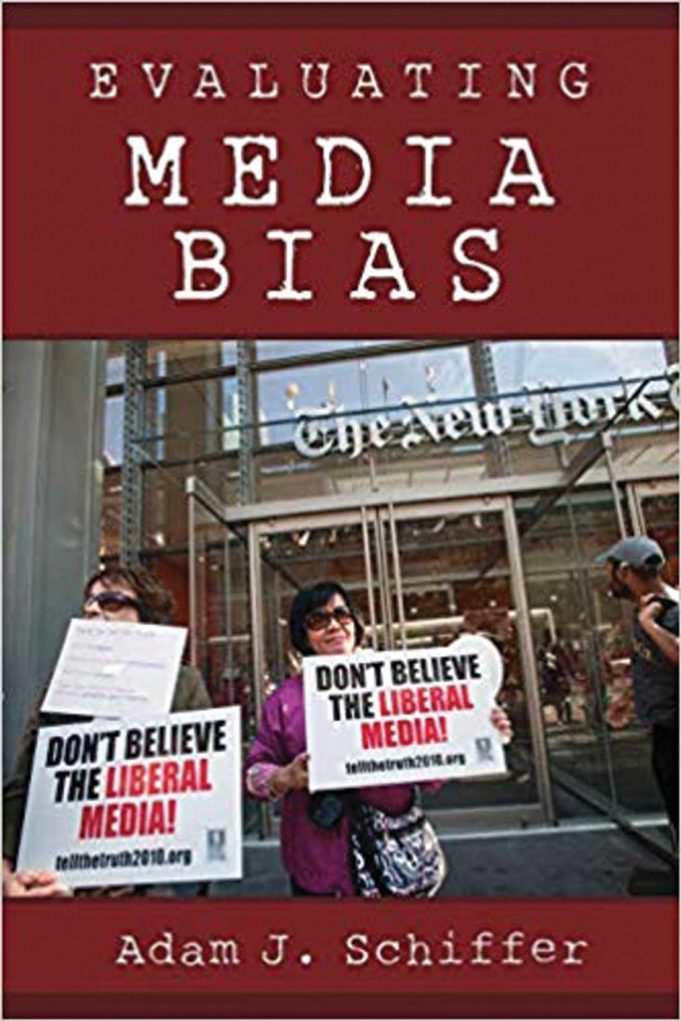

Adam Schiffer, an associate professor of political science at TCU, has written a book that examines whether the charge is true. Evaluating Media Bias was published by Roman & Littlefield last year, but its relevance has intensified as the First Amendment continues to come under unprecedented attack by the Trump administration.

Schiffer has long been interested in the topic of media bias. He wrote his master’s thesis on it, and “Media and Politics” has been his flagship course during the 15 years he has taught at TCU. In 2014, he decided to write a book that would serve as “sorely needed” middle ground between “popular polemic screeds by ideologically motivated critics” and hard-to-plow-through scholarly research. He wrote the theory for the book and locked up a contract in 2015, then wrote most of the chapters in 2016 with research help provided by political-science students.

We all know what else happened in 2016. There was a presidential campaign like no other, resulting in a president like no other.

As to the sweeping charge of a left-leaning media, Schiffer found no valid basis for that claim. He defends the press against accusations of prejudice in Chapters 2, 3, 5, and 6. Although Effron’s book “was the showpiece of the Nixon-era bias-charge bonanza,” he writes, “it violated some of the basic principles of sound social science, such as independent coding of subjective categories.” In Chapter 3, “How to Evaluate a Media Charge,” he provides a formula for determining whether there is truth in a bias claim. Not all bias, though, is partisan bias, and that’s where Schiffer found room for criticism. He wrote that favoritism in the media does exist, just not in the way that most people believe, with reporters giving short shrift to conservatives.

One criticism is that the media tends to favor government officials as sources on policy without seeking input from other stakeholders. An example is how the media covered the Affordable Care Act. A study Schiffer conducted of how Obamacare was debated in 2009 and 2010 revealed that government officials were overwhelmingly interviewed, along with random people on the street who had no specialized knowledge of the complicated policy. Missing in the reporting were the views of other important stakeholders such as doctors, hospital administrators, and insurance company executives.

Another failing is the tendency of the press during a presidential campaign to focus on what Schiffer called “horse race journalism” – which candidate is leading in the polls, for instance – rather than on policy issues that would help voters make better informed choices.

Schiffer devotes the final two chapters in his book to America’s election of a wealthy reality TV star to the nation’s highest office and the role the media played in that phenomenon. Chapter 6 is titled “The Media and the 2016 Republican Nomination,” and Chapter 7 is titled “Bias, Balance, and Ideals in the Trump era.” The academic found that, out of the initial Republican field of 17 candidates, Trump received far more free ink and airtime than all the other contenders combined. Though Schiffer acknowledges the difficulty of trying to report on so many candidates, he doesn’t let the media off the hook for allowing Trump to dominate the coverage. “By any reasonable standard, the media failed to meet not only the formidable challenge of structuring nominations in the direct-primary era but even the minimal task of providing citizens with substantive information about the candidate field,” he writes.

He quotes this from a column by the Washington Post’s Eugene Robinson, published in March 2016 and titled “No, the Media Didn’t Create Trump”: “To understate by miles, [Trump] knows how to draw attention to himself –– the late-night Twitter rants, the fire-breathing rallies, the gold-plated jet, the ridiculous hair. After decades in the public eye, he had more than 90 percent name recognition when he began his campaign, so it was no surprise that hordes of media flocked to Trump Tower last June 16 and watched him descend the shiny escalator for his kickoff announcement. Who doesn’t love a good sideshow?”

Although the intent of Robinson’s column was to absolve the press of blame where the rise of the controversial president is concerned, Schiffer writes that it instead highlighted reasons why the media deserves criticism: “The news media, through their commercially driven incentives and mandates, convey political reality through the warped prism of news-judgment criteria such as negativity, scandal, drama, novelty, simplicity, and personalization. Those are media [emphasis his] biases.”

The world may love a good sideshow, but that doesn’t necessarily mean the press should give the most coverage to the clown that best creates a circus atmosphere. The 2016 decision, and Schiffer’s thought-provoking analysis of how the media handled it, will hopefully be lessons for the media going forward.

Evaluating Media Bias, by Adam J. Schiffer

Rowman & Littlefield

150 pps.

$25.50-64

HaHaHaHa!!!!!! Yeah Right!