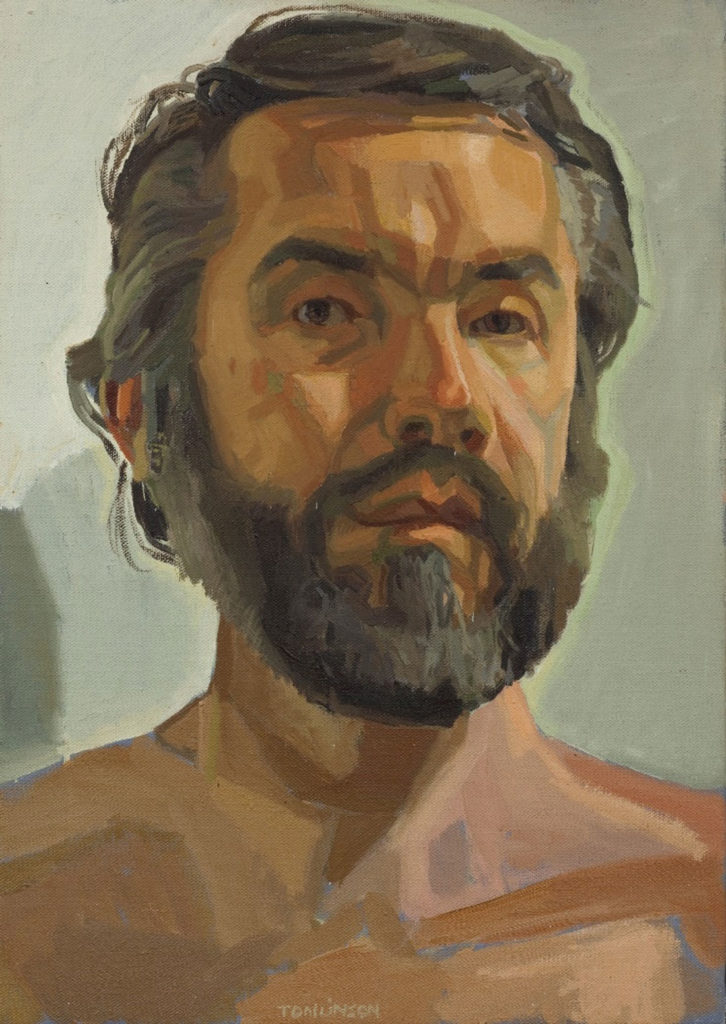

Ron Tomlinson was in fine form this past May when he and I sat down for a series of conversations at his Westcliff home. His front door would sweep open in a grand gesture and (though we were the only ones there), he would announce me as if he were ushering me into a Parisian salon. A hug (never a handshake), followed perhaps by an observation about the family of ducks in the front yard, and then he’d conjure up a plate of Persian dates in honey, a bowl of Spanish olives, or radishes rubbed with olive oil and salt.

We were meeting ostensibly to work on a feature story for this paper in advance of Tomlinson’s first Fort Worth show in some years. It was to be a retrospective exhibit, featuring a selection of paintings from his work of the past several decades. I had a list of interview-style questions for the Fort Worth artist, intent on my due diligence — but I’m glad to say I never managed to keep him on-track for more than a minute or two before we’d digress, diverge, and lose our way in the art of good conversation, of which he was a consummate master. Our talks would run late into the night before I would finally have to excuse myself, having accomplished nearly nothing on my list but feeling nonetheless that it had been an evening well-spent.

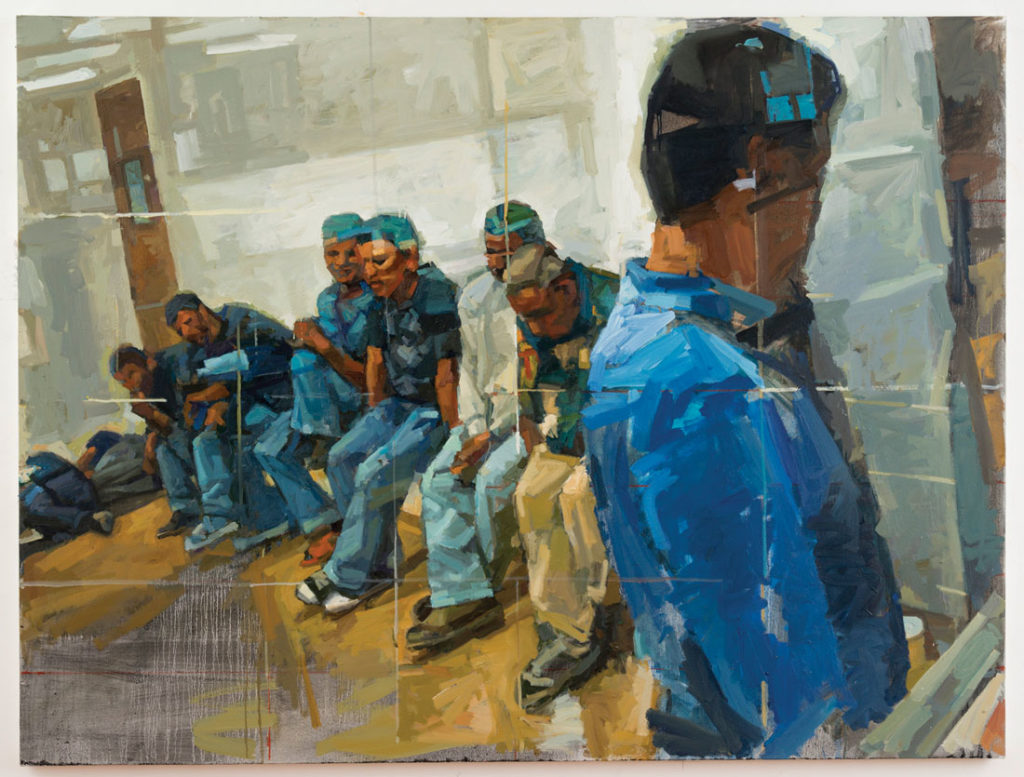

Tomlinson was restless, though, and having some reservations about his retrospective. He had recently returned from New York City (where he kept a studio and apartment) and had left behind his latest paintings, the Borders series, nine intense but very formal paintings and more than a dozen silkscreen prints depicting scenes of the detention and incarceration of economic migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border. And he wasn’t planning on bringing the series back to Fort Worth right away, even though he considered the paintings some of his best and most personal. Tomlinson was a working artist — a distinction he was both extremely proud of and considered something of a cosmic joke, that he’d actually made a living by painting, of all things — and he needed to sell some work. He wasn’t sure the Borders series was the right show for Fort Worth, but he was having a hard time getting excited about showing his older work, too.

He’d hinted about a new series he wanted to do, something that would make use of some of the silkscreen techniques he’d been experimenting with in New York, but he confessed, too, to what he called “painter’s block.” He wasn’t yet sure where he was headed, though he expressed confidence in the process, frustrating as it could be.

“You can’t be half-in with something like painting,” he said. “I have to paint constantly, and I have to paint a lot. You know what I mean? You can’t dabble. Just forget it. Well, no, go ahead and dabble, and after two days of dabbling, you might start painting — painting and then scraping it off. I’ve been scraping a lot off lately, more than I’ve ever done. Scraping it off is very forward to me. It’s not like erasing or starting over with a fresh canvas. It pushes me forward, particularly when I’ve found I’ve just been painting like Ron again. Well, who needs that?”

A few weeks later he had postponed his Fort Worth show, getting more than a few hopes up that the new series he had envisioned was taking shape.

Then, on September 23, Ron Tomlinson was found dead at his home. He was 73.

*****

On December 6, Artspace 111 opened Vecinos (Spanish for “neighbors”), an exhibition of 20 silkscreen prints originally produced by Tomlinson for Once We Were Strangers, a collaborative project with his friend and former student, Amir Akhavan. As part of his Borders series, these prints show a master’s deft command of form, composition, and technique while highlighting the essential humanity of their subjects — men, women, and children who leave their homes behind in search of a better life elsewhere. This is a fitting way to celebrate and remember the life and work of one of Fort Worth’s great painters.

Tomlinson was adamant about not being what he called an “issues painter” — he loved painting for its own sake, and painting was its own reward. He resisted the notion that his work, even when the subject matter was as poignant and topical as migrants being detained, was motivated by a social or political agenda. He would talk about a painting’s moment of apprehension, how it needed to stand on its own, aesthetically, and therefore mustn’t be “about” anything — and yet a pronounced sense of empathy pervades Tomlinson’s work.

Tomlinson had grown up in Fort Worth during the 1950s, where he had the good fortune to take art classes at the Fort Worth Children’s Museum, forerunner of the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History, then located in a house on Summit Avenue. The classes were taught by members of the Fort Worth Circle, an eclectic group of artists that included Bill Bomar, Dickson and Flora Reeder, and Bror Utter. Utter became Tomlinson’s first mentor, encouraging the young painter to pursue his artistic education.

Tomlinson’s parents supported his interest in art — his mother whole-heartedly, his military father less so.

“School was fine when it was all art and words, but then math came along, and then fourth grade long-division,” Tomlinson recalled. “I was hopeless, so my father, when he learned I was having trouble, sat me down and said, ‘Look, these numbers have to line up, and they have to be exactly under each other so that you don’t lose the 10s and the ones. … Oh, god. I just went to sleep.

“Well a long-division class came just before recess, and the way it worked with Sister Mary Whatever was that as soon as you finished two pages of long-division, you can go out, too. Well, I wasn’t getting to go out at all because, you know, I wasn’t even trying, and I noticed that every day little Sally Shaw would be the first one out to recess. She was straight A’s in everything. And I thought I was basically a moral person, but when it came to math, all bets were off. I would copy her work, no qualms at all, and so I always said I had to marry Sally Shaw because I never learned long-division.”

By the time he was in high school, Tomlinson was assisting Utter in teaching other students. Tomlinson continued to teach painting in some capacity for the rest of his life and counted himself extremely fortunate to have been able to divide his professional life between painting and teaching. When asked if he had ever found himself having to teach when he wanted to paint, he said, sure, but that he had also found himself having to paint when he wanted to teach. For him, these were two sides of the same coin, and he considered teaching to be a true privilege. He had learned so much from his students over the years, he said, and they helped him remember how to see, and that helped him know how to paint.

At Utter’s urging, Tomlinson moved from Fort Worth in 1962 to study painting, sculpture, and psychology at Boston University. Fort Worth had held few charms for an artsy kid with no interest in football, and when Tomlinson left town, he left (he thought) for good. After earning his Bachelor of Fine Arts at BU, he attended the elite residency program at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine where he met his next mentor, the painter Philip Pearlstein. Tomlinson continued to study with Pearlstein in New York City while earning an MFA from Brooklyn College.

It was during this time Tomlinson reconnected with Sally Shaw. The two married and kept an apartment on Hudson Street. Ron painted. Sally taught school in Harlem.

Tomlinson was well-connected to the New York arts scene of the 1960s, thanks to Pearlstein and Pearlstein’s good friend Andy Warhol. Tomlinson seemed on the verge of “making it” as an artist (“whatever that means,” he’d say flippantly) when Ron and Sally decided to leave New York and go live in the jungle.

“It was my dream, to go live in the jungle,” he said, “But she didn’t care. We were 23 and in love, and we didn’t care.”

The catalyst for this move (which Pearlstein opposed) seems to have been an appointment with the draft board in Fort Worth, which called Tomlinson home to stand for review. The Vietnam War was in full swing, and Tomlinson wanted no part of it. He had, in fact, considered the whole prospect of war too stupid to warrant much of his energy or attention (he would rather be painting), and so he was ill-prepared to articulate a conscientious objection to the draft board. Fortunately, he had made friends in New York from the Unitarian Church and the Society of Friends, who helped him prepare.

When Tomlinson’s day came, he got dressed, combed his hair, and went to see the draft board (“a bunch of old white men deciding who lives and dies”), where he made his case, quoting scripture when necessary. He got his deferment, which allowed him to serve instead in “a civilian job contributing to the national interest.”

As he was leaving the board, and feeling rather pleased with himself, he noticed the next young man waiting for his review. He was young, Tomlinson said, as though barely out of high school. He was Latino. He was wearing a torn shirt. And Tomlinson was overcome with the realization that this young man was going to be sent to war while he was not — and it had nothing to do with Tomlinson’s merit and everything to do with his privilege.

Tomlinson would describe this moment of apprehension as a turning point for himself as a person and as an artist. He talked about the task of the painter being to help people remember how they saw the world around them before they were “taught” to see it “correctly” — and this came to include, essentially, the task of helping us recognize the face of our fellows in all the myriad anonymous images of human suffering to which we have become collectively desensitized.

Somehow Tomlinson found a “civilian job contributing to the national interest” teaching art in the Virgin Islands, which had not been exactly what the draft board in Fort Worth had in mind for the artist’s deferment.

“I got a letter from the board, at our home in St. Thomas,” Tomlinson remembered. “It said, You are to report on such and such a date to San Antonio, Texas, where you are to wash floors at a veteran’s home for two years. Well, that’s illegal, right? They can’t tell you to do that. But I was always waiting for a knock on the door, men in black suits waiting to carry me off in handcuffs. In the Virgin Islands, can you imagine? They’d have stood out like sore thumbs.”

Despite the tension (and a few ultimatums), the couple managed to finish out their two years. When their term of service was over, Ron and Sally were happy to not come back to the United States right away, their recent experiences with the government having left them somewhat askance.

The couple found their way to the mountains of Costa Rica and settled near the Quaker community of Monteverde. They would spend 10 years there, building a house and starting a family. Ron taught painting, Sally taught English. “It was Eden,” Tomlinson said. “It was paradise. And eventually paradise gets boring.”

They had two young daughters now, and they wanted to expose them to the wider world.

The Tomlinsons weren’t sure where they wanted to live when they got back to the States, only that they were pretty sure Fort Worth wasn’t the place. Since both their families were here, though, they came back home while they planned to sort it out. Fort Worth had changed quite a lot in the years they had been away — “They’d built the Kimbell, for one thing,” Tomlinson would say — and the longer they stayed, the longer it felt like it might be a good place to raise their family.

Sally Tomlinson took a job with the Fort Worth school district, providing a measure of domestic stability that let Ron paint — a practice that he had never been able to “fence in.” He would sometimes need to paint all night or for days at a time.

“Sally kept doing the long-division,” Tomlinson recalled. “She did all the things I couldn’t do. She made sure lunches were packed and bills were paid, everyone got to the pediatrician, and then it freed me up to be there when other parents were stuck at work.

“Fort Worth was a good place for us. If we’d gone to New York, I wouldn’t have been able to pay the pediatrician with a painting.”

Courtesy of the artist.

Tomlinson’s work during this period of the early to mid-1980s was some of his most prolific and distinctive, as the jungle landscapes and still-life compositions of Costa Rica gave way to an electric jazz of chairs and shadows, reflections and refractions that engage the viewer through their intermediary space in a way that is visceral and sculptural. And though there are few human subjects in his work from this period, his pieces retain a core of intimacy, the furniture that holds our bodies standing for our vulnerability.

In the forward to Tomlinson’s catalog, The Language of Abstraction, artist Drew Snyder writes, “Tomlinson’s paintings are neither abstract nor realistic. Instead they straddle the two realms. Thanks to his immense technical skill, validated, for example, through his decade-long series of chair paintings, his works all succeed in giving us glimpses of something ‘real,’ be it a pan, a cigar, a motorcycle, or a human being. They all, on some level, speak the language of recognizable images. However, the means by which he attains such clarity is unequivocally abstract. … By representing the real world in its honest and abstract form, Tomlinson’s work offers us a world far more authentic than anything realism could ever offer while simultaneously surpassing the visual capacity of purely abstracted painting.”

Though he had once abandoned his prospects for a “career” as a painter in New York, Tomlinson began to find buyers for his work who would, in time, become patrons. They would give him the freedom to keep painting while doing his part to support his family.

He found new opportunities to teach as well, taking a position as artist-in-residence at Texas Wesleyan University, where he found to his horror that there were college freshmen from Fort Worth who had never been to a museum. He became the art director of the Reeder School and later helped to found Fort Worth’s Imagination Celebration. These appointments reinforced Tomlinson’s commitment to getting arts education into marginalized communities and working with underprivileged students. Through intense mentorship over many years, he would witness the power of art to transform the lives of his students, regardless of their backgrounds.

Though Tomlinson had long felt an ambivalence toward Fort Worth, he came to love it and think of it as home. He enjoyed his life here painting and teaching. He loved to journey away, and he loved to come back. All in all, he would say, things worked out pretty well.

“I’ve gotten to paint,” he said. “From the time I was 4 years old until today, I’ve gotten to paint. And I’ve lived in interesting places and done wonderful things. I have ducks living in my front yard, and there’s a cat around here somewhere. …

“I said, ‘Don’t stay in New York until you “establish something,” and then, you know, you get some money and go wherever you want.’ That game wasn’t what mattered. And I wasn’t worried, or I wasn’t realistic, but, of course, I wouldn’t trade those years in Costa Rica for anything. They were huge in my life, my wife’s life, and my children’s lives. And, of course, I wouldn’t trade Fort Worth for anything either, as strange as that sounds to say.”

*****

Ron’s early mentors from the Fort Worth Circle had been on to something, he mused. There was something here that was good for painting. Maybe it’s the light.

Sally Tomlinson died in 2015. In addition to being Ron’s tether to the Earth, she had been a much-loved teacher of languages at William James Middle School. Their home was known as a place of safety and acceptance for their students.

In recent years, Ron had enjoyed spending time with his family (his adult daughters and grandchildren) in Fort Worth, and painting — anywhere and anytime. Ron was generous, gregarious, magnanimous — an inexhaustible profusion of lush adjectives bound together with an intense sense of humor and compassion.

Vecinos: Ron Tomlinson

Thru Feb 2, 2019, at Artspace111, 111 Hampton St, FW. 821-692-3228.