’Tis the season for local theaters to cash in on holiday cheer with appropriately themed crowd-pleasers, filling their houses with happy throngs craving the comforting and familiar and buying themselves some leeway ahead of next season’s production of Waiting for Godot. Yuletide blockbusters can make or break the year’s budget for small theaters, and while there’s a trend toward darker Christmas comedies of late, feel-good classics still dominate the season. Perhaps nothing says “stuffed stockings” for stage companies like Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, the cash-cow that is for theater what The Nutcracker is for ballet — a sure thing.

Stage West’s production of Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol is in another category, a re-telling of the classic tale that is neither a cynical, postmodern deconstruction of the original nor an exercise in schmaltzy revisionism. Instead it takes some of the most well-traveled terrain in the Christmas canon and gives it a subtle reorientation, a gentle shift of perspective, just enough to keep audiences from getting too comfortable in a storyline they can probably quote by heart.

Spoiler alerts are unnecessary, as the play’s title fairly gives up the ghost. There are no sneak attacks, no shocking reveals, and no upending exposés slashing through the original text. Things are, for the most part, as they seem — but instead of seeing the story from the point of view of Ebenezer Scrooge (as we have hundreds of times before), we are afforded a glimpse into the life and afterlife of Jacob Marley, the sad old ghost who (as far as any of us knew) was doomed to spend eternity shuffling around Hell in the chains he forged throughout his stingy, miserly life. For anyone who ever thought this was a bum deal for Marley and tried to work out the theologics that give one miserable old son-of-a-bitch a second chance while dooming another to damnation, Jacob Marley’s Christmas Carol finally provides some answers, some closure — and a few more questions.

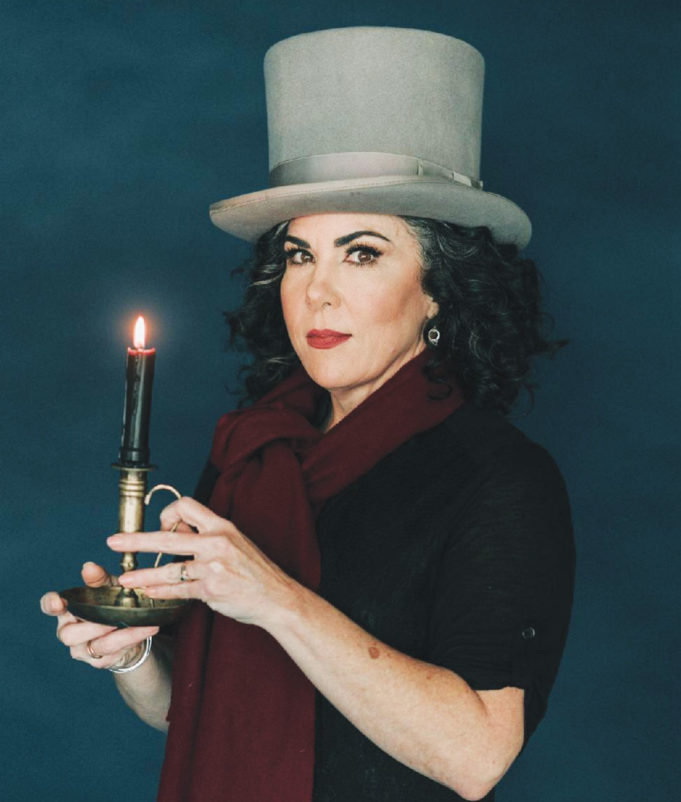

Stage West’s presentation of Tom Mula’s script is lively, precise, and engaging, with a customarily high production quality. Director Garret Storms and the Stage West production crew are especially deft at weaving mixed media into the staging in a subtle, understated way that fleshes out the one-woman show. Not that Emily Scott Banks needs any help. The award-winning actress and director delivers a virtuosic – even acrobatic – performance, inhabiting each and every one of the play’s many characters convincingly, switching between them effortlessly, slipping in and out of accents as she changes costumes mid-stage. Certainly Banks carries the show, but she also carries Mula’s script, which, at a run-time of little more than an hour, can read a bit thin in places.

The overall effect, though, is satisfyingly good fun. And if the play isn’t particularly fraught, it still lingers in ways that can catch one off-guard at odd moments in the days following a viewing. Mula’s 1994 script (and it’s strangely apt to think of 1994 as “a simpler time”) can certainly be taken at face value — a plain tale of redemption and salvation and the power of empathy over isolation. But Dickens’ novel is so deeply embedded in our collective consciousness, a foundational thesis on avarice that extends out far beyond the confines of the holiday season, that one feels there may be a bit more going on beneath the surface. Marley’s Ghost is (no surprise) sent back to Earth in a last-ditch attempt to save the soul of the wretched Scrooge, hoping to save himself in the process — but who really deserves a second chance? And what constitutes atonement or a change of heart substantial enough to set one’s course aright? Can a one-time act of kindness, self-sacrifice, or the scattering of a few coins in the air undo a lifetime of selfishness, cruelty, and deceit?

Tom Mula’s Marley seems more closely related to Michael Cohen than the Bodhisattvas — more than willing to have a change of heart when the consequences get real enough. Mula’s eternity — a bureaucratic nightmare of self-interested wights begrudgingly helping one another get promoted up the rungs from Hell to Heaven — isn’t sardonic enough to qualify as an outright satire, but it does suggest a sort of moral: Help probably isn’t coming, and neither is a second chance. Tend to your garden while you still can.

But musings aside, the best reason to get down to Stage West is to see Emily Scott Banks kick ass.